|

Several years ago, we observed that the celebrated Austen adaptations made in 1995 and 1996 “may suffer from being so fully attuned in their texture to our present tastes and imaginations that this texture will not always appeal so easily to future audiences” (Troost and Greenfield 11). Indeed, most of those productions have already been remade: 2005 saw the release of Joe Wright’s Pride & Prejudice with Keira Knightley, and in March and April of 2007, ITV aired telefilms of Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion, followed in January 2008 by the BBC’s three-part Sense and Sensibility. However much these films may repaint the past for a modern aesthetic sense, they are, like their predecessors, fairly traditional adaptations, maintaining period settings and avoiding plot features blatantly extraneous to the novels.

Between these two groups of Austen films, however, are five in a very different style. Patricia Rozema’s 1999 Mansfield Park rethinks the concept of both “adaptation” and “heritage drama,” altering and politicizing plot and character while preserving a period setting. The four other films, the focus of this essay, adopt the approach of the 1995 film Clueless by rethinking everything—plot, character, and setting. These films are the Tamil-language Kandukondain Kandukondain (2000), directed by Rajiv Menon; Sharon Maguire’s film of Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001); Andrew Black’s Utah version of Pride and Prejudice (2003); and Gurinder Chadha’s Bollywood-style musical, Bride & Prejudice (2004). These four contemporary-setting films utilize what is convenient in Austen’s tales but update plots and settings, alter characters, broaden or divert the satire, and reposition the moral framework. They do not represent Austen adapted to modern media and morals but Austen appropriated to particular modern cultural positions. They also reveal what filmmakers and audiences in the early twenty-first century find compelling or repelling in Jane Austen’s novels.

What the writers and directors behind the four updates find regrettable is Austen’s lack of advocacy for women’s careers (other than as wife). In addition, her jaded attitude toward many families and communities, out of line with our modern, idealized sense of these as havens, causes consternation. Directors around the globe share these reactions, suggesting that these films—despite their emphasis on specific geographic places and cultures—actually participate in a shared global response to Austen’s work. What most fascinates the writers and directors from India to America are Austen’s focused descriptions of the family’s place within a social structure of a local and limited community, the tensions within the family, and the relationship of the male outsiders and potential mates to that family structure. Thus, Austen’s intense localism paradoxically allows Austen, in this generation of films, to go global. The search for a soul mate and the relationships of sisters and parents in a tight community can be duplicated easily and naturally, whether in Amritsar or Provo.

In the novels, the heroine’s personal integrity is validated by the love of a worthy man, and Austenian heroines do not, prior to the final clinch, have many opportunities outside their family to achieve other types of success—displaying one’s accomplishments to a Lady Catherine de Bourgh is not professional validation. It is different in the modern world. When Cher Horowitz, the Emma character in Clueless, has to “make over” her soul, she does so by running a successful disaster relief effort at her high school, displaying management skills in a way that the novel’s heroine cannot. Repeatedly, in these film adaptations, the heroines, be they modern or early nineteenth century, have a profession at which they succeed. Each may get her man, but none of them defines her success solely by this accomplishment: they want both the man and a career.

This careerist impulse is common in recent Austen-connected films. Patricia Rozema’s Mansfield Park does the makeover by giving Fanny Price Austen’s own profession, fiction writing. The recognition of her superior talent comes from Edmund Bertram quite early in the movie, and the film ends with the mention of a publisher’s willingness to print Fanny’s writings—rather, Jane Austen’s juvenilia that have been incorporated in the screenplay. Also, of course, the justification for the 2007 feature film Becoming Jane is to emphasize the importance of the professional writing career. Unlike Fanny Price, however, young Jane Austen does not get her man—but Tom Lefroy can serve as a catalyst for her literary talents—and who needs marriage when there is such a career to develop?

Bridget Jones’s Diary

Even that modern singleton, Bridget Jones, wants professional validation. Finding a career is as central to her life as finding a boyfriend. Helen Fielding began Bridget Jones’s Diary as a weekly newspaper column in The Independent on 28 February 1995, presenting anxieties about modern life and work in the context of current events in Britain. Bridget starts out in publishing and has an affair with her boss, Daniel Cleaver, but he dumps her for Emma Thompson, the star and screenwriter of the recently released film Sense and Sensibility (4 Oct. 1995). When Darcymania hits the U. K. during the broadcast of the BBC Pride and Prejudice, Bridget is affected, too. She develops a fixation on Colin Firth, which, interestingly, immediately helps her land a new job. At her interview, she tells Richard Finch that Wake Up Britain should pursue “the off-screen romance between Darcy and Elizabeth” (18 Oct. 1995), and that is the beginning of her new career in television. Not until the following year, however, does the appropriation of Austen’s plot start. In the column of 3 January 1996, the Mark Darcy character first appears, and Bridget Jones is refashioned into Elizabeth Bennet.

The parallels to Pride and Prejudice are more strongly developed in the novel published in October 1996 and in the 2001 film. The first meeting of Bridget and Mark now comes at the start of the narrative; the Pemberley sequence (a party at Mark’s house in Holland Park) and the elopement are both given more extensive treatment. The Wickham role is split between Daniel and Julio/Julian, allowing Mark Darcy to be a romantic rival of one and to provide the extraordinary rescue of Bridget’s mother from the other (additional parallels are noted in Whelehan). The film adaptation deletes the Darcymania section of the book, but there are other Austen jokes included. The publishing firm at which Bridget initially works is named Pemberley Press, a detail not in the novel, and Mark Darcy is played by Colin Firth, fusing Bridget’s fantasy with reality. But the film, like others of its kind, develops Bridget as a career woman as well as a romantic heroine. The rescue that Mark Darcy performs near the end is not only that of a straying relative but also of Bridget’s career. Mark gets her an exclusive interview with a Kurdish freedom fighter, which saves her job with Sit Up Britain. Even Mrs. Jones leaves her husband temporarily for a career (as well as another man). The lack of professional feminine development in Austen’s novel is something that current derivative films feel a strong need to amend.

Kandukondain Kandukondain

Similarly, a sense that the rewards of a companionate marriage and wealth are not enough for the modern Austenian heroine appears in the Bollywood musical Kandukondain Kandukondain. On first glance, this Tamil production from southern India seems to have little to do with Sense and Sensibility. After all, the film opens with machine-gun fire, a battle scene, and a land-mine explosion that rips off a man’s leg. Eventually, we figure out that we are seeing, in backstory, the wounding of Major Bala, the Colonel Brandon character. But the plot becomes recognizable soon enough. After the death of the patriarch, the all-female household is forced to abandon their family estate in favor of obnoxious relatives. The two sisters, as well as their younger sister and mother, move to a small apartment in Chennai (Madras) and find jobs, disappointment, and, eventually, true love and success.

In the wet-sari number early in the film, Austen’s characters also emerge. This scene shows us the sisters contrasting in their attitudes about matters of the heart. Meenakshi, like Marianne, insists on poetry and passion; Sowmya, like Elinor, has lower romantic expectations. As is customary in a musical, the songs reveal the characters’ personalities and desires. The discussion between the two sisters segues into a production number showcasing Meenakshi’s poetic sensibility, filmed in a lovely rural setting with a variety of back-up dancers and several sari changes. Kandukondain Kandukondain gives preferential treatment to the sister with sensibility in this production number, setting her up as the central character of the film by surrounding her with positive images of nature (grain and fields) and national culture (white elephant masks and Kathikali dancers in their distinctive makeup and costumes).

© 2000 Sri Surya Films

Austen’s plot is followed fairly closely for the rest of the film but altered for the values of the modern world. Both sisters get their men, of course, after undergoing roughly the same pattern of courtship and disappointment that Marianne and Elinor do, but they also get professional satisfaction. Meenakshi pursues a career in singing, rising rapidly to stardom. Sowmya advances from telephone receptionist in a large corporation to a top computer programmer. At the end of the film, she is offered a job with the company’s division in the United States. Interestingly, at the conclusion of the film, the family has a chance to return to their Norland-like mansion, but they turn it down, being thoroughly integrated into professional life in Chennai. Though a third of the world away from Bridget Jones’s London, this Indian film also validates its heroines through their careers: one can see this desire as part of global culture.

Kandukondain Kandukondain, however, started out as a distinctly local, not global, film. The movie was conceived originally for a south Indian audience, and the focus in the film is entirely on Tamil culture, with little desire to export that culture. One can identify the concentration on the local market by looking at the original DVD, released in 2000 for an expatriate audience. The cover shows the main title in Tamil script with a transliteration into the Roman alphabet but no English title. The ungrammatical subtitles sometimes lag a full minute behind the action depicted on the screen. Nor is there any mention of Jane Austen on the cover or in the credits.

Austen is present insofar as Emma Thompson’s Sense and Sensibility is the real point of inspiration. Kandukondain Kandukondain contains details from that film that do not appear in the novel: an older male who presents a musical instrument to the young woman he admires, an older sister who bursts into tears in front of her lover at the very moment she learns, against her expectations, that he still desires her, and a double-wedding finale. There seems to be no homage to Austen’s novel, only echoes of Thompson’s screenplay.

Despite its localism, the film is enthusiastic about the process of mixing Western and Indian cultures. Manohar, the Edward Ferrars equivalent, is a budding film director, much to the disappointment of his controlling parents, and he is currently appropriating the Keanu Reeves/Sandra Bullock film Speed to an Indian setting. Educated in America (and called “Mr. New York” at one point), Manohar wishes to make an American-style film pitched in one emotional key, but he runs into conflicts: for instance, his potential backers want to know how he will do musical numbers on a train. They want the smorgasbord approach—something for everyone—that dominates the Tamil film industry. After giving several speeches about how he must remain true to his vision, Manohar gives in: he mixes his emotional keys and includes the obligatory extravagant and varied dances.

The final product, so far as we can tell, mimics Kandukondain Kandukondain itself, with its pirated plot, numbers varying from traditional Indian dances to Michael-Jacksonesque sequences, and songs filmed in such puzzling places as among the Egyptian pyramids and in a Scottish castle. Manohar’s film, a hodge-podge to our American eyes, is a smash success and, in being a hybrid product, seems to be exactly what the local Tamil audiences want. In other words, the globalism of the film is part of the local scene, and Austen is one part of that mix. Writing of post-1990 Bollywood films in general, Suchitra Mathur notes the paradoxical nature of this fusion: “This enthusiastic celebration of globalisation . . . is, interestingly, not seen to conflict with Bollywood’s explicit nationalist agenda; the two are reconciled through a discourse of cultural nationalism that happily co-exists with a globalisation-sponsored rampant consumerism, while studiously ignoring the latter’s neo-colonial implications” (Mathur 12). The famous line from Thompson’s Sense and Sensibility that “piracy is our only option” (50) seems borne out in a postmodern, postcolonial southern India, where appropriation of western culture and values seems an inevitable, even desirable part of local taste.

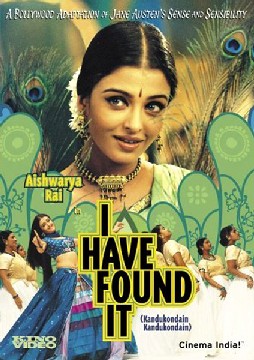

Rajiv Menon’s film, however, has not been allowed to wear its Austenism unselfconsciously. The film was too good and too recognizably connected to the western commodity that is Jane Austen to get away with merely local success. In 2005, a reissued DVD appeared, aimed at a wider audience. It features elegantly translated and accurately timed English subtitles, an English name (I Have Found It), and a banner on the cover proclaiming it as “A Bollywood Adaptation of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility.” The film makers are, of course, opportunistically happy to take success on the wider scale if Austen is going to provide it, and the film has succeeded partly because it made the same choices that Western adaptations have made: like Bridget Jones’s Diary, the film now features references to Austen (at least in its marketing) and emphasizes the importance of both love and career as a path to fulfillment.

Bride & Prejudice

One reason for the reissued DVD, with Aishwarya Rai’s face dominating the cover, was the release in October 2004 of Gurinder Chadha’s Bride & Prejudice, with the actress who had played Meenakshi now shadowing Elizabeth Bennet and performing in English. This Bollywood-inspired British film from the writer-director of Bend It Like Beckham is less comfortable, however, with the process of interpenetrating cultures than Kandukondain Kandukondain. Instead of the happy absorption of some western values, the film shows “cultural difference as the foremost source of social tension” (Wilson 328) through the uneasy courtship of Punjabi Lalita Bakshi and American Will Darcy, the character of the Americanized Mr. Kohli, and the seduction of Lalita’s sister Lakhi by the young Englishman Johnny Wickham. It is the more moralistic film, but also the more complicated one. As Cheryl Wilson notes, it “is and is not Jane Austen, is and is not Bollywood, and is and is not Hollywood” (330). Bride & Prejudice is also the one recent Austen film in which the professional possibilities for the heroines seem muted: having let avocation top romance in Bend It Like Beckham, perhaps Chadha feels no need to bang that drum again; it is just assumed that a job is important for a woman. For example, Mrs. Bakshi is eager to have her daughters marry Indian men living the U. S. or the U. K. because, once they move abroad, the girls will be able to “earn more” (the parents, alas, cannot afford to provide “decent dowries” for all four daughters). A career is a given in this world, even if one has a husband.

The plot of Bride & Prejudice overtly follows that of Austen’s novel, but Gurinder Chadha’s film is not about the meeting of different social classes; it is about the mingling of various cultures. The two main characters run into conflict at their first meeting, as Lalita misunderstands Darcy’s ideas on the ideal woman (thinking he wants them “subservient”) but correctly understands that he regards India as “beneath” him. As Chadha describes him, Darcy is “a handsome American, as opposed to an ugly American, but he has enough attitude to need a good Colonialism/Imperialism 101 from Lalita” (Roy-Chowdhury). Lalita proudly defends “the real India” against “imperialists” like Darcy, who want to turn her country into a “theme park” for westerners by acquiring a luxury hotel in Goa; later, we learn that her rebuke has had an effect: Darcy dissuades the board of directors from acquiring the hotel.

© 2004 Pathé Pictures

Yet, despite a mutually suspicious Indian Elizabeth and American Darcy, the film inevitably heads toward cultural combination once they get past their pride and their prejudice. At the start of the film, Darcy has endless trouble with the drawstrings of his Indian trousers (just as he has trouble adapting to the culture); by the end of the film, he is confidently playing an Indian drum (albeit in western garb) for the sort of crowded celebration that previously made him uneasy. He has not gone native, but he has learned to combine east and west successfully. Lalita also learns to adapt. She starts out as a “skeptic of globalism” (Seeber), but her views turn out to be prejudiced, and she learns to moderate them, at least where Darcy is concerned. Cultural mingling is inevitable, but unlike in Kandukondain Kandukondain, it is a cause for concern. Lalita worries about overseas development in India, but that is minor compared to what the importation of western values can do. English backpacker Johnny Wickham gets far deeper into Indian society than the wealthy Darcy, and his relaxed sexual mores nearly corrupt Lalita’s youngest sister.

Hybridization has the potential to do great damage, but it also has its comic side, illustrated in the character of Mr. Kohli, a green-card-carrying California accountant, who stands in for Austen’s Mr. Collins. In Amritsar to find a “traditional” bride who is not “outspoken and career-orientated,” he combines the worst aspects of American and Indian attitudes—the materialism of one and the sexism of the other. Lalita, while defending Indian values when with Darcy, nevertheless rebels against them when Mr. Kohli is in the picture.

© 2004 Pathé Pictures

In “No Life without Wife,” Lalita reveals herself to be more hybrid than the typical “demure, sari-clad, conventional [Bollywood] heroine who is untouched by any ‘anti-national’ western influence” (Mathur 10). Lalita may not be shown as explicitly aspiring to a career, but she certainly will not tolerate being a stay-at-home wife who does the cooking while her husband earns the money. Lalita wants a modern, western marriage: “I just want a man with real soul / Who wants equality and not control.” The song to which the sisters sing and dance, a Grease-inspired melody with rap overtones, could not illustrate western music and values more strongly. More than she realizes, Lalita herself exemplifies an ideal fusion of eastern and western values.

© 2004 Pathé Pictures

In Austenian terms, the entire project of Bride & Prejudice is very different from that of Kandukondain Kandukondain. The Tamil film expects no knowledge of the novel or the Thompson film; Chadha’s expects little knowledge of Bollywood but wishes to introduce it and India to a western audience. “I want to show a multicultural blend in the film. I do not have a home in India but I love Punjabi culture. I want to show it on a global level and make it popular” (“Gurinder”). Chadha’s film seems aimed at the Darcy-like prejudices of the west that view Indian society as quaint. The point of the film is to be global and succeed globally, even while preserving some postcolonial indignation at Anglo-American cultural failings. Austen becomes a vehicle to criticize the limitations of both cultures but also to affirm their positive values.

The values affirmed in these new incarnations, however, are not always the novels’ values, and this shift goes well beyond the professionalization of heroines. The attraction of Austen’s stories derives in part from the focus on a small-town family with important, but decidedly limited, connections to a broader world. In other words, her global appeal depends upon her localism as well as her emphasis upon family structure. At the same time, however, Austen’s depiction of the family is the most problematic attitude adapters confront. Austen repeatedly portrays parents as foolish or selfish (sometimes both). A few relations receive kind treatment by the author, but many others are the focus of satirical attacks. Furthermore, Austen uses marriage to free her heroes and heroines from claustrophobic family networks (Emma is the major exception). Film adapters, valuing the family and regional focus of Austen, like her because that narrow focus on community and family can easily translate to a defense of a local culture or a defense of the concept of family itself, but Austen’s jibes at parents and family must be toned down or avoided.

In Bride & Prejudice, for instance, for all its globetrotting, the Bakshi family is both a narrative and a moral center. Will Darcy even acknowledges the superiority of Indian family life. When asked what he likes about Indian culture, he replies, “I think it’s nice the way the families come together,” and he contrasts this with his own dispersed, broken family. Moreover, the Bakshi family receives a much “nicer” portrayal than the Bennets. There is really nothing to criticize in the father, as Barbara Seeber has noted. He is much less selfish and critical of others than Austen’s Mr. Bennet. His wife is more of an exhibitionist than the original Mrs. B, but she is also less destructive of her daughters’ chances with their beaux. Even the daughters satirized in the original are toned down: Lakhi, though she is a great flirt and runs off with Wickham, actually feels remorse for what she has done, unlike Lydia. Maya is desirous of showing off her accomplishments (she plays the sitar and, at one point, performs a hilarious Cobra Dance), but she is not a righteous prig like Mary Bennet.

The makeover of the family, and particularly of the parents, goes back to Clueless, where Cher’s fierce, strong father is vastly more aware and wise than Austen’s hypochondriacal and silly Mr. Woodhouse. Likewise, in Thompson’s Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Dashwood, though emotional, is prudent and thoughtful, unlike the novel’s character. Her derivative, Sowmya’s and Meenakshi’s mother in Kandukondain Kandukondain, has hardly any flaws. And, as Seeber has noted, the latest film of Pride & Prejudice totally remakes the parents in its quest to “foreground family”: Mrs. Bennet explicitly and sensibly can defend the economic necessity of her attempts to promote the marriages of her daughters while Donald Sutherland’s Mr. Bennet becomes “a sensitive and kind father” and is so far from his cynical self that he actually weeps near the end of the film. Austen’s novels are about family, but what she has to say about it is often not particularly “nice”; the current filmmakers desire her focus but not her strongly satiric attitude.

As well as providing an affirmation of family life in a very unAustenian way, Chadha’s Bride & Prejudice celebrates what is local: she provides an homage, not only to Austen but to the town of Amritsar and its Golden Temple: “There is no substitute for the traditional elements of Amritsar in the world!” (“Gurinder”). We get from Lalita repeated defenses of both India in general and Amritsar in particular, long shots of contented field workers, and an opening musical number linking the upcoming wedding of Lalita’s friend and the overall joy of the town. The town is an extension of the family and defended just as firmly. While Austen details the rhythms of life in small towns, the best she can say about any of them is that Highbury gave Emma “no reason to complain” (233). Austen is useful because of her localism, but the attitude toward the local and familial is not what modern screenwriters and directors want.

Pride and Prejudice

Similarly, the 2003 Pride and Prejudice, set in a Mormon community in Utah, adapts a tight set of people to a distinct local space, finding enough cultural similarity between Meryton and Provo to make many parallels. This is a good-natured film, like its cousin Napoleon Dynamite (whose director features in a cameo role), but it is so anxious about Austen’s satiric treatment of the family that it eliminates it from its narrative. Parents are not given personality makeovers; they are removed entirely from the plot and protected from all criticism, nor is there an equivalent to Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Elizabeth, Jane, Mary, Kitty, and Lydia (only the last two are sisters) are housemates who attend what is presumably Brigham Young University. They have the interests of typical Mormon college women: going to school, attending church, studying genealogy, frolicking at alcohol- and caffeine-free parties, and meeting potential husbands. As in Bride & Prejudice, the Bennet-Darcy class difference is represented by national difference: Darcy is an Englishman, visiting American friends.

Of course, the film has to find ways of professionally validating the heroine outside of her ability to attract Mr. Darcy. Like Fanny Price in Rozema’s film, or Jane Austen in Becoming Jane, Elizabeth has ambitions of becoming a writer. The opening scene of the film presents this information in voice-over, and we see several shots of her working on the Great American Novel in a variety of sublime mountain landscapes. We also see her at work in a bookstore, where the “cute meet” with Mr. Darcy, a customer, takes place. The scene serves as a good equivalent for Darcy’s comments at the Meryton assembly, replacing the personal with the professional, in keeping with modern concerns. Annoyed by her chatter as he hunts for a particular book, Darcy assumes Elizabeth is as incompetent professionally as she is socially. He thinks her too dim to know who Kierkegaard is, and he jumps to the conclusion that she is the one who has been misshelving books. He hurts her by slighting her work and complaining to the manager.

© 2003 Bestboy Productions

The professional remains center stage in Elizabeth’s later clashes with Darcy. She has her first novel accepted for publication and is invited to lunch by the editor, only to discover herself dining with Darcy, who owns the publishing house. In a parallel to the first proposal scene (the restaurant is even called Rosings), Darcy points out—in excruciating detail—all the ways in which her novel, albeit publishable, is deeply “flawed.” Like the novel’s Elizabeth Bennet, who rejects Darcy’s offer of marriage when her family is insulted, the offended author rejects Darcy’s offer of a publishing contract when her work is insulted. For this Elizabeth, a woman of the modern world, a career is just as important as marriage, but it must be on her own terms.

Modern heroines need professional validation, but they also get a place on the world stage as part of the triumph. At the conclusion of Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth is offered a last-minute job as a teaching assistant in the university’s study-abroad program in London, where she once again encounters Darcy and, we assume, eventually marries him. Bride & Prejudice and Kandukondain Kandukondain also show heroines able to succeed after some fashion in both local and global worlds. Lalita moves smoothly and confidently in Indian, British, and American social circles, and Sowmya is given a chance to work in the company’s American office. (Whether she takes the job is unclear at the end of the film—what matters is that she has the potential and the opportunity.) Even hapless Bridget Jones enters the global scene—admittedly, somewhat parodically—by bravely surviving a stint in a Bangkok prison, described in the columns (28 Aug.–18 Sept. 1996) and in Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (in which Bridget and Mark start channeling Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth instead of Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy).

All in all, we see these four Austen appropriations rewarding the worth of their heroines with romantic, professional, and international success. Nor need they sacrifice their tight social groups for their men. Getting the guy is great and having a career is fine, but maintaining close ties with family or friends, even while taking on the world, is also essential. The four films, from very different cultures and variously celebrating their distinctive locales, to some extent turn out to be from the same culture, a global one that bends Austen’s texts in the same direction. They wish to use Austen for a celebration of women’s triumphs, but their heroines must have professional abilities in addition to moral worth. The films appropriate Austen as a vehicle to celebrate community, family, and friendship but are not willing to adopt her critical eye toward these social entities. The modern cinematic world wants her characters and plots—and certainly her name, as she can be a key to commercial success—but since some of her attitudes are not marketable, she does not fit comfortably, as is, anywhere on the face of the cinematic globe. Fortunately, she can be made over, and the makeovers, from India to England to America, turn out, oddly enough, to look somewhat alike. A common global culture shines through these highly localized adaptations.

NOTE: All clips used in this essay satisfy the criteria for fair use established in Section 107 of the Copyright Law of the United States of America and Related Laws Contained in Title 17 of the United States Code.

Books and Articles Cited

Austen, Jane. Emma. Ed. R. W. Chapman. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1933. Bridget Jones’s Diary. Dir. Sharon Maguire. Screenplay by Helen Fielding, Andrew Davies, and Richard Curtis. Working Title Films/Miramax, 2001. Fielding, Helen. Bridget Jones’s Diary (columns). Bridget Jones Archive. http://bridgetarchive.altervista.org. See “Library.” _____. Bridget Jones’s Diary (novel). London: Picador, 1996; New York: Viking, 1998. _____. Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason. London: Picador, 1999; New York: Viking, 2000. “Gurinder Chadha goes to Amritsar.” Redriff India Abroad 2 Oct. 2003. http://www.rediff.com/movies/2003/oct/02chadha.htm. Mathur, Suchitra. “From British ‘Pride’ to Indian ‘Bride’: Mapping the Contours of a Globalised (Post?)Colonialism.” M/C Journal 10.2 (2007). http://journal.media-culture.org.au/0705/06-mathur.php. Roy-Chowdhury, Sandip. “Hollywood meets Bollywood.” India Currents 1 Feb. 2005. http://www.indiacurrents.com/news/view_article.html?article_id=eb8cd0c60aafeb133eb95f94b11b2341. Seeber, Barbara K. “A Bennet Utopia: Adapting the Father in Pride and Prejudice.” Persuasions On-Line 27.2 (2007). Thompson, Emma. The Sense and Sensibility Diaries. London: Bloomsbury, 1995; New York: Newmarket, 1996. Troost, Linda, and Sayre Greenfield, eds. Jane Austen in Hollywood. 2nd ed. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 2001. Whelehan, Imelda. Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary: A Reader’s Guide. London: Continuum, 2002. Wilson, Cheryl A. “Bride and Prejudice: A Bollywood Comedy of Manners.” Literature/Film Quarterly 34 (2006): 323–31. Adaptations Cited Becoming Jane. Dir. Julian Jarrold. Screenplay by Kevin Hood and Sarah Williams. BBC/Miramax, 2007. Bride & Prejudice. Dir. Gurinder Chadha. Screenplay by Paul Mayeda Berges and Gurinder Chadha. Pathé Pictures/Miramax, 2004. Clueless. Dir. and screenplay by Amy Heckerling. Paramount, 1995. Kandukondain Kandukondain. Dir. and screenplay by Rajiv Menon. Sri Surya Films, 2000. Rereleased on DVD as I Have Found It. Kino Video, 2005. Mansfield Park. Dir. and screenplay by Patricia Rozema. BBC/Miramax, 1999. Mansfield Park. Dir. Iain B. MacDonald. Screenplay by Maggie Wadey. ITV, 2007. Northanger Abbey. Dir. Jon Jones. Screenplay by Andrew Davies. ITV, 2007. Persuasion. Dir. Adrian Shergold. Screenplay by Simon Burke. ITV, 2007. Pride & Prejudice. Dir. Joe Wright. Screenplay by Deborah Moggach. Working Title Films/Focus Features, 2005. Pride and Prejudice. Dir. Andrew Black. Screenplay by Anne K. Black, Jason Faller, and Katherine Swigart. Bestboy Productions/Excel Entertainment, 2003. Sense and Sensibility. Dir. John Alexander. Screenplay by Andrew Davies. BBC, 2008. |