|

It is not yet a truth universally acknowledged that Jane Austen’s reception has followed Shakespeare’s footsteps. Long is the story of the English Bard as a literary character: Edward Bond’s play Bingo (1973) and Susan Cooper’s King of Shadows (1999) are but two cases in point. Whereas the former portrays Shakespeare as a selfish capitalist who commits suicide, the latter is a children’s novel in which the hero returns to the past and meets the playwright in Renaissance England. The different nature and audiences of Bond’s and Cooper’s works illustrate Shakespeare’s wide range as a literary character. Probably the most famous example is his appearance in the oscarised Shakespeare in Love (1998). Prominent scholars of Shakespearean film, like Kenneth Rothwell and Richard Burt, have delved into this movie, considering it a milestone in the history of Shakespearean adaptation.

Although the history of Jane Austen as a literary character is certainly not as long as Shakespeare’s, she has also been depicted as a fictional character on various occasions. Me and Mr. Darcy (2007), Alexandra Potter’s rewriting of Pride and Prejudice, presents the novelist as a matchmaker transferred into the twenty-first century to help the new Elizabeth Bennet, Emily, and her Mr. Darcy, Spike, come together. The biopic Becoming Jane (2007) focuses on Jane Austen’s real-life short romance with the law student Tom Lefroy. Another example on screen is Jeremy Lovering’s Miss Austen Regrets (2008), a BBC film based on the novelist’s last years, which looks back to the reasons why she never married.

Jarrold’s Becoming Jane is particularly interesting as it follows the path opened by John Madden’s Shakespeare in Love. The numerous intertextual connections between both movies can be reduced to one: just as Shakespeare is imagined as the hero of his own play, Jane Austen becomes the heroine of her own novel. In formulating the key ideas of intertextual theory, Roland Barthes has referred to the unavoidable connection between different texts. Barthes claims that “the citations which go to make up a text are anonymous, untraceable, and yet already read: they are quotations without inverted commas” (160). Meaning thus comes from the intertextual quality of language. In Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane, the “already read” becomes the “already watched.” And that intertextual connection centers on their common use of the true and the false: both begin and end similarly (and truthfully) while deceiving us in the middle. Frank Kermode, in The Sense of an Ending, has highlighted the importance of beginnings, middles and ends inside and outside the written page. The connections between the two films’ respective beginnings, middles and ends reveal that Shakespeare as a literary character paves the way for the representation of Jane Austen.

I. The beginning: the creative block

To begin with the beginning, as Byron would say, both films share a similar opening, but also an ending. According to Kermode, we are born in medias res, and to give sense to our lives, to the middle, we require fictions with beginnings and ends: “We hunger for ends and for crises. ‘Is this the promis’d end?’ we ask with Kent in Lear” (55). Plots relate the future to the past and to the middle, allowing us to join the beginning and the end. Because of the scarcity of evidence, in the particular case of Shakespeare and Austen, we are allowed to invent the middle. Although Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane, following Kermode’s ideas, start and finish faithful to historical records, halfway through the movie they lie. If beginning and end are the same (i.e., truthful), it seems that the middle does not matter, or not so much, from a historical perspective. Therefore, the middle can be invented; provided the result is going to be the same, what happens just before that is not so important. The two biopics suggest this idea: since we are going to reach the same final point, we can take either the road of history or that of fiction and speculation.

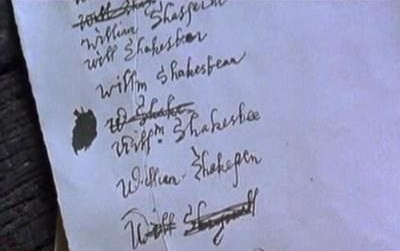

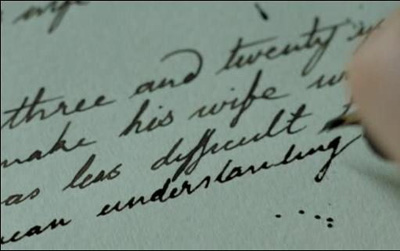

There are two main similarities in the movies’ beginnings. Shakespeare and Austen both are suffering from serious creative blocks, and they are writing trash when the films open. Shakespeare is unable even to start Ethel, the Pirate’s Daughter while Jane Austen pens dull prose, with difficulty completing a short piece on her sister’s engagement. The frustrated writers are portrayed at their working desks trying to scribble just a few lines. With dirty fingers, Shakespeare complains about the loss of his Muse. Meanwhile, he scrawls an untidy manuscript in a handwriting, to a modern eye, somewhat like Jane Austen’s, both the fictional and the real one.1 In her night gown, the novelist similarly struggles with her pen, trying to find some of her missing inspiration in music while the chiming clock signals the passage of unproductive time.

In the case of both Shakespeare and Austen, the creative block will be overcome thanks to the beloved’s influence. Love for Viola de Lesseps and Tom Lefroy serves as inspiration to create their masterpieces: the Bard pens Romeo and Juliet, one of his most famous plays, and Austen composes her much-loved novel Pride and Prejudice. Both films thus confirm the old rule according to which authors must write from first-hand experience; they must undergo love directly before writing about it. All works, both biopics suggest, are partly autobiographical; they have an origin in life. Further, in these films, the authors’ goals are the same: both aim to be true-to-life. Elizabeth I complains, “Playwrights teach us nothing about love. They make it pretty, they make it comical, or they make it lust. They cannot make it true,” and wonders, “Can a play show the very true nature of love?” Shakespeare, “the poet of true love,” will prove that it can. Similarly, Jane Austen will cry, “A novel must show how the world truly is, how characters genuinely think, how events actually occur. A novel should, somehow, reveal the true source of our actions.” Ironically, this “truth” about fiction will be represented by lying: in order to represent it, both films deceive us about the authors’ lives. But they do it in the middle.

II. The middle: living/writing love

“In the middest,” Kermode points out, “we look for a fullness of time, for beginning, middle, and end in concord” (58). Just as Shakespeare in Love builds on the plot of Romeo and Juliet, Becoming Jane builds on Pride and Prejudice. In Becoming Jane, then, what we have is the already seen, the already watched. Even if for Barthes a text’s intertextual connections are infinite and cannot be listed or traced back, in the case of Austen’s biopic, at least one of them can. One of the echoes or citations without quotation marks in Becoming Jane is, undoubtedly, Shakespeare in Love, as Richard Burt has noted in his review of Jarrold’s film, where he focuses on the association between books and female sexuality in the biopic, considering books as metaphors of Jane Austen’s development as a writer (63). Together with Pride and Prejudice, Shakespeare in Love is one of the cultural codes contained in the film. Common to both biopics are four main lies connecting the authors’ love relationships and their writing practices, their ends and beginnings: the encounters with fellow writers, the balls, the goodnight scenes, and the writing processes themselves.

Both films suggest that Shakespeare’s and Austen’s meetings with fellow authors contribute to their creative process. In Shakespeare in Love, Will meets Christopher Marlowe, who hints at possible ideas for Romeo and Juliet. Similarly, in Becoming Jane, the novelist pays a visit to Ann Radcliffe in London. The author of The Mysteries of Udolpho, which Jane Austen parodies in Northanger Abbey, encourages the young writer to become a professional novelist. Both encounters have a positive effect on Shakespeare’s and Austen’s respective productions; they spur their writing. Whereas Shakespeare is in constant competition with Marlowe, Becoming Jane shows solidarity between the two women.

As in many a Shakespeare play and Jane Austen novel, balls are essential in both movies for the lovers to interact socially. “To be fond of dancing was a certain step towards falling in love” (Pride and Prejudice 9). In Northanger Abbey, Henry Tilney “consider[s] a country-dance as an emblem of marriage” (76). The ball in Shakespeare in Love reproduces Romeo and Juliet’s initial masquerade. Likewise, the one in Becoming Jane recalls the Meryton Assembly in Pride and Prejudice, where Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy first meet. The films depict similar scenes, with Viola and Shakespeare, Tom and Jane dancing together.

The second dance in Becoming Jane parallels that of Shakespeare in Love even in its soundtrack. The ball allows both pairs of lovers to display their feelings in public. It is, in fact, after their dance together that Jane bravely declares her love for Tom, and even kisses the law student herself. The novelist’s actions in taking the initiative after the dance contribute to move the plot forward, presenting her as a feminist avant la lettre.

If the lovers dance passionately, they show the same passion when saying goodnight. Just as Shakespeare and Viola have their own balcony scene, Jane and Tom, while staying at his uncle’s in London, part in an analogous fashion. After saying goodnight hesitatingly, they go back and are about to kiss before leaving for their respective rooms. “I really must say goodnight,” claims Tom reluctantly, just as Shakespeare bids Viola “a thousand times goodnight” because “parting is such sweet sorrow that I shall say good night till it be morrow.”

Finally, Shakespeare’s writing process prefigures Austen’s. In Viola, the playwright finds his muse; Austen finds a male muse in Tom Lefroy. While Shakespeare starts composing his masterpiece immediately after seeing Viola for the first time at the ball, Austen pens the initial pages of First Impressions, the original version of Pride and Prejudice, the night before Tom talks to his uncle about their engagement. The image of both writers at work is very much alike: they scribble their manuscripts in an old-fashioned handwriting with the help of quill and candle. The two movies shoot these scenes similarly, emphasizing elements like the writing materials, the authors’ dirty manuscripts, and their handwriting. With these long shots, the biopics stress Shakespeare’s and Austen’s professional career.

Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane are also in dialogue with plays and novels by these authors besides Romeo and Juliet and Pride and Prejudice. Shakespeare in Love ends with a reference to Twelfth Night and All’s Well that Ends Well; Becoming Jane incorporates allusions to Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility, Mansfield Park, and Persuasion. As Joseph Fiennes’s playwright composes sonnet twelve to Viola in the early stages of the film, the speech of Jane Austen’s father contains quotations from her letters, for instance when he claims his daughter to be “a picture of perfection” (23 March 1817). Both Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion are also drawn into Becoming Jane when Mrs. Austen asks her husband to persuade Jane to marry Wisley. This intertextual dialogue contributes to the tapestry of quotations without inverted commas Barthes talked about and complicates the intertextuality of both movies.

Besides the four intertextual “lies” and the dialogue with other works by these authors, there is a further source of intertextuality between Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane: the star system. According to Keith A. Reader, the star system, and the concept of star itself, is one of the specific features of filmic intertextuality: the star system relies on the similarities and differences between one film and another, and even on the correspondences between the characters’ lives on screen and the actors’ lives off screen. A whole network of actors moves across the screen in Shakespeare and Jane Austen film adaptations, reinforcing the connection between the derivatives of both authors’ works.

The network of travelling actors is vast. Sir Laurence Olivier’s casting in Shakespearean and Austenian roles represents an example of the interconnection between both writers’ afterlives. Olivier, famous for his Shakespearean stage and film performances, including Romeo, Henry V, Hamlet, and Lear, played Mr. Darcy in the 1940 dramatization. Curiously, he was a Montague in 1935, just before his impersonation of Austen’s hero. More recently, Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet, Elinor and Marianne Dashwood in Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility, have also visited Shakespeare’s world. Before playing Elinor, Thompson played Katherine in Branagh’s Henry V and Beatrice in his Much Ado About Nothing; later, Winslet was Ophelia in Branagh’s Hamlet. These journeys illustrate how the influence between Shakespeare’s and Austen’s domains works in multiple and contradictory directions.

Some of the stars of Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane have also travelled among adaptations of the two authors’ works. Colin Firth, for instance, became famous in 1995 for his highly sexualized incarnation of Mr. Darcy.2 He subsequently starred in an adaptation related to that version of Pride and Prejudice, Helen Fielding’s modern Bridget Jones’s Diary. In Shakespeare in Love, Firth plays the haughty, arrogant Lord Wessex. Thus proving again that intertextuality does not only work in one direction but that multiple filmic intertextuality does exist, Firth journeys from the BBC Pride and Prejudice to Shakespeare in Love, and from Shakespeare in Love to Bridget Jones’s Diary. James McAvoy, the hero of Becoming Jane, travelled in an opposite direction. Interestingly, he performed the role of Romeo in Wooding’s Bollywood Queen, a sort of modern West Side Story with a Hindi Juliet and a British (Anglo) Romeo. He also enacted Macbeth in Shakespeare Retold before reaching the Jane Austen domain with the character of Tom Lefroy in Becoming Jane. Finally, Anne Hathaway, named after Shakespeare’s wife, plays the heroine of Becoming Jane and is a peculiar instance of this interconnectedness. This network of moving actors strengthens the association between Shakespearean and Austenian film adaptations. The star system brings together these specific movies but also, more generally, the adaptations of Shakespeare and Austen, exposing their mutual influence.

Thus Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane engage intertextually through the common lies—the hero or heroine’s encounters with fellow writers, the balls, goodnight and writing scenes—as well as through the texts and actors that appear in the central sections of these films. But where is the truth, then? The truth is at the end.

III. The end: the lovers’ farewell

“The end changes the past,” Kermode claims (183), but, whether we believe it or not, what is clear is that we cannot change the end; instead, the end changes us. History cannot be rewritten. Shakespeare, we know, did not marry a woman named Viola de Lesseps, just as Jane Austen did not marry Tom Lefroy and bear him six red-cheeked Irish children. Although the end cannot be altered, however, it can be interpreted—as Madden and Jarrold have done through the middle. “All ends well,” Henslowe says in Shakespeare in Love. How? We don’t know: it’s a mystery. But does it really end so well for Shakespeare and Jane? There is a brief moment of hope for the romantic plot when Shakespeare and Viola consider eloping. In Becoming Jane there is another such moment, when Tom and Jane try to trick his uncle into approving their match, and another when they decide, like Lydia and Wickham, to elope. Hope soon vanishes, however, for in this intertextual dialogue both biopics share analogous sad endings. They depict unhappy love stories, in which, at the end, the lovers are inevitably separated.

Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane are stories of frustrated love in which the playwright and the novelist channel their suffering through their creative activities, producing some of the most important masterpieces in English literature. Their fictional suffering is used to define their artistry. Both their respective partners must wed others for financial reasons: Viola’s family, albeit rich, needs Wessex’s title; likewise, Tom, coming from poor Irish parents, is dependent on his uncle and must marry an heiress. Viola and Tom have already fulfilled their purpose. They have served as inspiration, as the fuel that allows both authors to continue writing, and to write well. The two films end as they began, with the authors at their working desks, struggling with their manuscripts—but this time with better results. Nonetheless, their respective love stories affect Shakespeare’s and Austen’s works differently. Since Will Shakespeare cannot marry Viola, he decides to create a tragic ending for his play. “Oh, it’s sad and wonderful,” Mr. Fennyman, the “Moneyman” cries. “It is not a comedy I am writing now,” the playwright says, and, if the lovers are reunited, it will be only in Heaven. By contrast, Jane Austen’s romance with Lefroy has the opposite effect. “My characters will have, after a little bit of trouble, all that they desire,” Anne Hathaway’s Austen tells her suitor Wisley, who answers, “It’s good to come to good ends. It’s a truth universally acknowledged.”

And the happy ending of Pride and Prejudice has indeed become universally celebrated. According to Becoming Jane, Jane Austen wants to supply her heroines with the romantic fulfilment she cannot have in life. In a conversation with her sister Cassandra, she summarizes her intentions for First Impressions:

Cassandra: Letter? Jane: No, it’s something I began in London. It is a tale of a young woman, two young women, better than their circumstances. Cassandra: So many are. Jane: And a gentleman who is much better than he deserves to be, as very many do. Cassandra: How does the story begin? Jane: Badly. Cassandra: And then? Jane: It gets worse. Cassandra: How does it end? Jane: They both make triumphs and have happy endings. Cassandra: Plenty of marriages? Jane: Yes, to very rich men.

The beginning, middle and end of First Impressions, then, relate to those of Becoming Jane, with the difference lying in the ending. Both works narrate love stories with “bad” beginnings and middles, but the heroines, unlike the novelist, will make triumphant love-marriages at the end.

The ending of Shakespeare in Love, despite being as melancholy as Becoming Jane’s, can be deemed more hopeful, to some extent. The movie closes with a new beginning: that of Viola in Virginia, but also of Twelfth Night. The Queen wants a new play although this time it must be a comedy. “What will my hero be? The saddest wretch in all the kingdom. Sick with love,” Shakespeare muses. Yet, as Viola realizes, “it’s a beginning.” If Marlowe has given Shakespeare some ideas for Romeo and Juliet, Viola now makes up the plot of Twelfth Night, with the difference that this time all ends well. This biopic’s ending confirms Angela Carter’s idea that “we start from our conclusions” (191). Shakespeare’s and Austen’s genius commenced from their conclusions, that is, from the conclusions of their respective love affairs. Yet, in the case of the English Bard, his new start, accompanied by a new play, is to some extent positive as it engenders two new beginnings.

In contrast, Becoming Jane’s ending is more tragic due to the addition of a scene with the middle-aged Jane and Tom. The novelist has already published some of her works with great success. Tom has married and has several children. They meet at the concert of an operatic soloist, which the lawyer attends with his daughter, named Jane, a sign that Tom is still in love with the writer. In addition, the excerpt from Pride and Prejudice the author reads aloud at this assembly, featuring Elizabeth Bennet’s feelings for Mr. Darcy once she has realized that he is the perfect man for her, reveals her continued affection. All hope seems gone for Elizabeth, after Lydia’s elopement with Wickham, just as now there is no hope for the forty-year old Jane and Tom. Interestingly, this additional scene is itself a lie: Jane and Tom never met again, as biographers Park Honan and Claire Tomalin have noted. Why this extra passage then? This picture of middle age renders Becoming Jane more mournful and dramatic. The film’s ending focuses on what the heroine has lost emotionally rather than on the excitement of a new beginning for her, and since Austen died in her early forties, this is really an ending—her ending.

In conclusion, the parallels drawn between Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane expose a clear intertextual relationship between the two biopics. But the differences between Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane—for instance, the nature of their endings—hint at gender inequality. Women, Becoming Jane implies, cannot have their cake and eat it. Whereas male authors, like Shakespeare, are granted relatively happier resolutions, Jane Austen cannot be both emotionally and professionally successful. The re-workings of the novelist’s life follow this path, as exemplified by the latest biopic Miss Austen Regrets, which features a mature and professional Jane Austen and explores her relationship with her niece Fanny Knight. Miss Austen Regrets takes the mournful ending of Becoming Jane to the extreme, portraying as well a successful writer who cannot be happy in love. And now, the only thing left for us to say is: “A thousand times goodnight.”

NOTES

1. Jane Austen’s handwriting can be seen in the manuscript of Sanditon, The Watsons and the cancelled chapter of Persuasion. For more information on these manuscripts, see B.C. Southam.

2. Aragay and López comment on Darcy’s physicality in this version which, they argue, is partly created by the female viewer. This emphasis on the body, together with a sexualized approach to the Austen world seems common to recent adaptations. In the words of Hudelet, “One of the main characteristics of the recent spate of Austen adaptations in the 1990s seems to be their emphasis on the body, through the attention to sensuous period details or to the desire relationships between the characters. This aspect becomes paradoxical if one takes into account the common idea that there is a general ‘lack of body’ in the novels themselves” (175).

Works Cited

Aragay, Mireia, and López, Gemma. “Inf(l)ecting Pride and Prejudice: Dialogism, Intertextuality, and Adaptation.” Books in Motion: Adaptation, Intertextuality, Authorship. Ed. Mireia Aragay. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2005. 201-19.Austen, Jane. The Novels of Jane Austen. Ed. R. W. Chapman. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1933-1969. _____. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1997. Barthes, Roland. “From Work to Text.” Textual Strategies: Perspectives in Post-Structuralist Criticism. Ed. Josue V. Harari. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1979. 73-82. Bond, Edward. Bingo. London: Methuen, 1974. Burt, Richard. “Backstage Pass(ing): Stage Beauty, Othello and the Make-Up of Race.” Screening Shakespeare in the Twenty-First Century. Ed. Mark Thornton Burnett and Ramona Wray. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006. 53-71. _____. “Becoming Literary, Becoming Historical: The Scale of Female Authorship in Becoming Jane.” Adaptation 1 (2008): 58-62. Carter, Angela. The Passion of New Eve. London: Virago, 1997. Cooper, Susan. King of Shadows. London: Penguin, 1999. Honan, Park. “Jane Austen and Marriage.” Contemporary Review 245 (1984): 253-59. Hudelet, Ariane. “The Role of Sound in the Recent Film Adaptations.” Persuasions 27 (2005): 175-84. Kermode, Frank. The Sense of an Ending. New York: Oxford UP, 1968. Potter, Alexandra. Me and Mr Darcy. London: Hodder, 2007. Reader, Keith A. “Literature/Cinema/Television: Intertextuality in Jean Renoir’s Le Testament du docteur Cordelier.” Intertextuality: Theories and Practices. Eds. Judith Still and Michael Worton. Manchester: MUP, 1990. 176-89. Rothwell, Kenneth. A History of Shakespeare on Screen. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. Southam, B. C. Jane Austen’s Literary Manuscripts: A Study of the Novelist’s Development through her Surviving Papers. Rev.ed. London: Athlone, 2001.

Tomalin, Claire. Jane

Austen: A Life.

New York: Vintage, 1997.

films Cited

Branagh, Kenneth, dir. Hamlet. Perf. Kenneth Branagh, Derek Jacobi, Kate Winslet, and Judi Dench. Castle Rock, 1996. _____. Much Ado About Nothing. Perf. Kenneth Branagh, Emma Thompson, Keanu Reeves, Denzel Washington, Kate Beckinsale, and Robert Sean Leonard. BBC,1993. Jarrold, Julian, dir. Becoming Jane. Perf. Anne Hathaway, James McAvoy, Julie Walters, James Cromwell, and Maggie Smith. Miramax, 2007. Langton, Simon, dir. Pride and Prejudice. Perf. Colin Firth, Jennifer Ehle, David Bamber, and Crispin Bonham-Carter. A & E, 1995. Lee, Ang, dir. Sense and Sensibility. Perf. Emma Thompson, Kate Winslet, Hugh Grant, Alan Rickman, and Gemma Jones. Columbia, 1995. Leonard, Robert Z., dir. Pride and Prejudice. Perf. Lawrence Olivier and Greer Garson. MGM, 1940. Lovering, Jeremy, dir. Miss Austen Regrets. Perf. Hugh Bonneville, Adrian Edmondson, Tom Goodman-Hill, Sylvie Herbert and Olivia Williams. BBC, 2008. Madden, John, dir. Shakespeare in Love. Perf. Gwyneth Paltrow, Joseph Fiennes, Geoffrey Rush, and Judi Dench. Miramax, 1998. Maguire, Sharon, dir. Bridget Jones’s Diary. Perf. Renée Zellweger, Colin Firth, Hugh Grant, and Gemma Jones. Little Bird, 2001. Moffat, Peter, dir. Shakespeare Retold: Macbeth. Perf. James McAvoy, Keeley Hawes, Joseph Millson and Toby Kebbell. BBC, 2005. Wooding, Jeremy, dir. Bollywood Queen. Perf. Preeya Kalidas, James McAvoy, Ciarán McMenamin, and Kat Bhathena. Arclight Films, 2002. |