|

The field of literary studies has enjoyed enormous transformations in content and methodology over the past 200 years, as is evident from even a cursory glance at book and essay titles of work focused on Jane Austen. While many Austen fans and scholars have relished the scope and depth of analysis that has resulted from these transformations, we are increasingly challenged to summarize Austen’s accomplishments or even her context, let alone delineate her legacy to students.

In considering the influence and the legacy of this writer in particular, the first question is what belongs to the “oeuvre”? Letters, juvenilia, works in other genres (e.g., The History of England . . . By a Partial, Prejudiced & Ignorant Historian)? What about all the film adaptations and collections of essays about them? How do they bear witness to Austen’s accomplishments as well as her ubiquity? Literary criticism and biographies are givens in an advanced classroom, but what about the sundry and numerous examples of the Jane Austen industry—the magazines, the web sites, and the “domestics,” so to speak, including mugs, aprons, notepads, advice books, cookbooks, imitation topaz necklaces, period music collections, and so on?

For educators, these questions involve more than making decisions about what should be offered to students via a course syllabus. More fundamentally, what might a simultaneous and inclusive look at the literary output, critical response, and popular industry associated with Austen offer us in the classroom? How might it help us actively engage students in research about the author and generate enthusiasm for both process and product?

Equally important issues are at stake as to what kinds of resources should be collected as research materials for a course that attempts to examine the full legacy of Austen as well as to the kinds of spaces in which such research should be conducted. Libraries are the traditional location of research by students of literature, but collections of texts and criticism on open library shelves, in specialized research databases, and in rare book rooms are now often equated with the resources that can be found by anyone via the internet, at the local movie theater, and in shop windows. The classroom offers a provocative place in which to bring these many resources together and to give students an opportunity to explore firsthand what is involved in putting together a coherent representation of an author’s legacy. But the library is still a unique and important place that students overlook at their peril, public in outlook though committed to the support of private inquiry as well as to the preservation of literary legacies. Can it too be used more creatively by students of Austen and other authors to enhance their classroom experience, as not only a place in which to learn but a place in which to exhibit that learning—indeed, to learn by exhibiting?

Some promising answers to these many questions have emerged in recent years through collaborations between librarians and a professor of English teaching three iterations of an undergraduate seminar devoted to Austen at two liberal arts colleges in upstate New York. Phyllis Roth, Professor of English at Skidmore College—who also visited for one semester at Union College—worked with librarians Wendy Anthony at Skidmore and Annette LeClair at Union to direct the creation of exhibits on Austen’s legacy in association with each of the seminars. Students themselves designed and mounted the exhibits as part of their course requirements. But in each case the Austen exhibit was hosted by the library, giving students a public space—and very public responsibility—for examining and ultimately presenting Austen’s legacy in a coherent fashion. In essence, the questions above were turned over to the students as a way of engaging them not only with Austen but with the kinds of issues that all literary scholars must be able to address.

Students began actively to prepare their exhibits about two-thirds of the way through each term. By that point they had become familiar with one or two of the most influential essays on the novels (students worked with the Norton Critical Editions for background material and often canonical analyses) and were acquainting themselves with radically diverse views of Austen’s work, including those possibly most denigrating, such as the opinions of Charlotte Brontë, D. H. Lawrence, and Mark Twain. Students also studied and discussed D. W. Harding’s key essay in the history of Austen criticism, “Regulated Hatred: An Aspect of the Work of Jane Austen” (first published in 1940). This still destabilizing essay alerted them to the fact that, even in the first half of the twentieth century, Austen’s critics were beginning to recognize her “complex intention as a writer.” Observations such as Harding’s—that “her books are, as she meant them to be, read and enjoyed by precisely the sort of people whom she disliked; she is a literary classic of the society which attitudes like hers, held widely enough, would undermine” (167)—prepared students to abandon pre-conceived notions and look upon all aspects of Austen’s work and reception with fresh eyes.

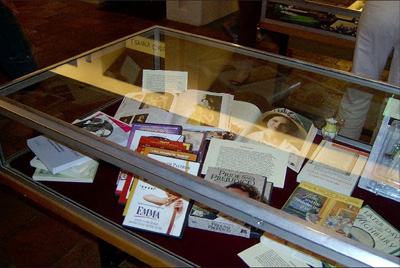

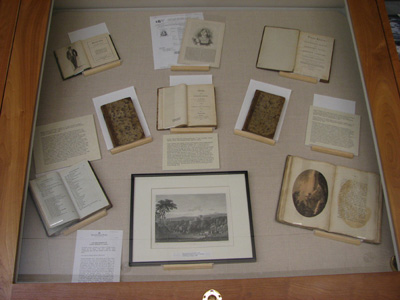

Each class was presented with an unsorted welter of material that Roth had amassed personally (Fig. 1): editions of Austen’s novels and writings, professional literary criticism, current films and CDs related to Austen, popular appreciations and continuations of her novels, and every kind of Austenalia imaginable (thank you, eBay). Students were also invited to add material they gathered from local stores, their own researches, and the library’s collections. At Union they had the particular pleasure of using works from its rare books collection, including a three-volume first edition of Pride and Prejudice as well as early editions of William Gilpin’s Observations, Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty and other collected essays.

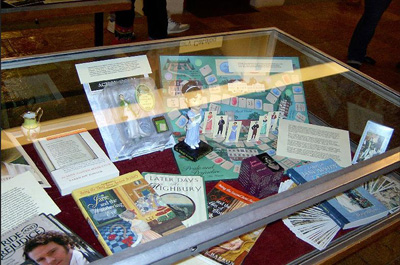

The students received only general guidance. That is, they were told to create an exhibit with a central organizing focus to play out over the four to six exhibit cases made available to them by the library. Imagine, then, the challenge of contextualizing and deploying Union’s first editions beside present-day items such as the Bollywood Bride and Prejudice or Jane Austen in Scarsdale: Or Love, Death and the SATs. After the students had examined the widely disparate material available to them (Fig. 2), they selected a focus, identified subtopics, and broke into smaller groups to create displays in each of the exhibit cases, moving in discussion within and among the groups to re-examine continually the connections between their focus and the subtopics they had chosen.

Reassured by an important metaphor, the students quickly understood that what they were doing was creating a visual version of a piece of writing with a thesis and supporting paragraphs, and that the visual required some help from the written. They also soon recognized that blurbs for the public cases and for particular items required a type of liveliness and attractiveness that the most skilled writers evince in their prose. More, students in all three seminars realized that the exhibit cases would comprise a chronological experience for the viewers. Thus, as in a clear, coherent piece of writing, the audience would be led from one deliberate view of the subject to others, views more specific, typically, than those in the first case. It was up to the students to collaborate, to explore rather unusual modes of learning, and to negotiate whose case had the best claim to a particular image of Jane Austen, for example—or of Colin Firth.

As their work progressed, students also realized that the layout of the items in a given case would make an important statement. For example, the sheer quantity of material presented in a case could make one kind of point.

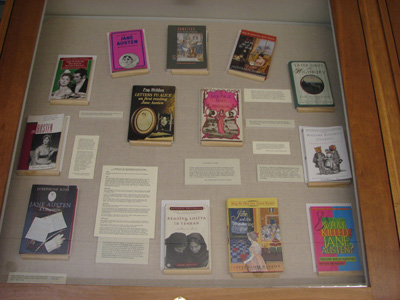

Figures 3 and 4. Skidmore exhibit case featuring films and Austen industry.

In all three exhibits, students decided to pack a case devoted to the movie adaptations in order to emphasize how numerous those adaptations are. Different kinds of points could be made by juxtaposing disparate items (for example, placing Victorian-era portraits of Austen next to Melissa Dring’s recent forensic effort), by framing a key object (such as a facsimile of an Austen letter or an e-mail solicited by the students from one of her descendants) with extra space or a colorful border, by using a direct quote from one of Austen’s novels as an alternative to a lengthy exhibit label in order to highlight a given object, or by taking advantage of the chronology of Austen’s growing legacy to build transitions both within cases and across the entire exhibit.

The Skidmore students in the spring of 2004 took the latter approach and organized their cases more or less in accordance with the chronology of Austen’s reception and influence, beginning with a case focused on the “gentle Jane” portrayed in her nephew’s memoir. The second case attempted in a small space to demonstrate succeeding and richer readings of Austen, those complicated by later and competing senses of what she was “really about” in her novels. Case three demonstrated Austen to be a living presence among us by highlighting the film adaptations, which students realized also constitute interpretations. A fourth case, taking the preceding one as a springboard, provided a sense of the expanding Austen industry beyond the films.

The seminar students at Union in the fall of 2006, struck by how Austen’s novels not only have lasted, but have ultimately permeated our culture, radically sharpened the contrast by naming their exhibit “Jane Austen: Then and Now.”

Figures 5 and 6. Sample Union cases.

Union’s first editions from Austen’s era were placed in one case back-to-back with modern re-workings of her novels in another. Particularly multidisciplinary in approach and ambition, this group also sought out manikins and rented costumes to emphasize the dichotomy of their theme (Fig. 7), and they arranged for “classic” and “contemporary” versions of Austen film adaptations to be playing on screens in the background of their exhibit. In fact, “breaking out of the cases”—reflecting the ways in which Austen herself continues to exceed the bounds of her era and of critical categories—became something of a hallmark of the Union exhibit. Students marked the entrance to their display with wall hangings mixing memorable quotations from and about Austen, and they created and printed a challenging quiz that invited visitors to match the first and last lines of the six completed novels (and to take it home for study if need be).

Perhaps nowhere did this group “break out of the cases” to better effect than at the opening reception for their display, where a group of English Country Dancers soon had the students, faculty, librarians, family members, and guests from the community dancing in the library lobby in proper Regency style to period tunes (Fig. 8). “I finally get all that dancing in the novels!” exclaimed one seminar student afterwards. Accustomed to active learning through their work on the exhibit, the students were not only willing to attempt the complicated maneuvers and changes of partners in the country dances but also perceptive enough to “get” thereby the crucial social interaction involved in dance scenes in Austen’s novels and to grasp the ways in which some of the moves prefigure prospective marital harmony. And they also began to see the library in a new light, as a place where learning could be fun and interactive as well as challenging in surprising ways.

Finally, the third exhibit, once again at Skidmore in the spring of 2007, echoed earlier themes but established its own focus. By calling their exhibit “The Many Images of Jane Austen,” the students in this group took direct aim at the question: which Jane is the real Jane or is she all of them? They described their inspiration in their exhibit statement:

One can imagine Austen’s surprise at the longevity of her work and the many avenues it has taken. The question then becomes, who is this woman and what is it about her that has inspired such a readership—such curiosity, such admiration, such affection? Or, occasionally, such distaste. . . . [I]n imagining how we could provide a vivid, engaging suggestion of all that is Jane Austen, . . . we thought back to what first engaged us, what surprised us despite whatever degree of familiarity with her work we had when we came to the course.

From this sense of their own shared surprise at what they hadn’t known about Austen, they devised an exhibit to juxtapose the gentle Jane image with the satiric, sometimes bawdy Jane (represented by such strikingly suggestive titles such as Madame Bovary’s Ovaries, Sibling Love and Incest in Jane Austen’s Fiction, and Pride and Promiscuity: The Lost Sex Scenes of Jane Austen) in order to demonstrate how more recent interpretations often depend on background material. Although their portrayal of the evolution (or “radicalization”) of thinking about Austen was distributed across the entire exhibit (Fig. 9), the Skidmore students also dramatized it within individual cases such as the one devoted to Austen’s settings. In that case, students highlighted conflicting views by, at one end, rendering a display of landscape images à la picturesque (Fig. 10), placing most decidedly three, not two, plastic cows in a cluster next to their pictures and, at the other, featuring material that examined “The Notion of Improvements” and “Improvements as Social Critique in Mansfield Park.”

These students, too, had a sense of the extraordinary language of Austen’s novels, interspersing quotations from them throughout the cases. Such quotations served a wide variety of purposes. Some, for example, demonstrated points of view or characteristic styles of speech (“‘[I]t is always incomprehensible to a man that a woman should ever refuse an offer of marriage’” [Emma 60]). Others illustrated topics of critical contention about Austen or her subject matter (“[F]rom politics, it was an easy step to silence” [Northanger Abbey 111]). Still others were chosen simply to entertain or “shock” exhibit visitors in the voices of Austen’s own characters (“‘Of Rears, and Vices, I saw enough. Now, do not be suspecting me of a pun, I entreat’” [Mansfield Park 60]). Like students in the other two seminars, this group also concluded their exhibit with a case representing the massive and varied industry generated by the seemingly universal appeal of her novels and the adoration that Austen herself elicits (Fig. 3 and 4).

All three exhibits were gratifyingly successful in generating enthusiasm for their subject among the students and exhibit visitors. But how did the students themselves characterize what they had learned from putting together their displays of Austen’s legacy? Students in all three seminars had an identical reaction to the sheer amount of raw material on Austen that was made available to them: they were overwhelmed. But this reaction became an important “fact” for them as well as a foundation for their subsequent work. As one Skidmore student noted, the impact of seeing the vast numbers of editions, literary criticism, films, and what the student called “tschotchkes” laid out before her on day one “was the most powerful thing for me.” Several students emphasized that physically seeing and touching evidence of even a small part of Austen’s legacy made it palpably clear to them that Austen matters to many people—even to those who, as another student noted in wonder, aren’t necessarily readers of Austen’s works. “It brings home how pervasive [she is], how loved,” said a student from Skidmore. “She’s just a big part of everyday life for people.”

This realization alone was transformative for many students. Several of them described its impact in terms of their fundamental attitude to the seminar itself. They were suddenly able to see that the point of studying Austen is not to fulfill a requirement but to begin to try to understand why she matters and more specifically how she matters. Not that they came up with definitive explanations for all of this richness—rather, their key insight was their engagement in the process. For at the same time that they tried to absorb the scope of Austen’s legacy and interpret it for their exhibits, they came to appreciate (more than to suffer frustration at) the multiple levels, the disagreements, the allusions, the interactions—the complexities, in other words—of readings through time and across diverse audiences. They soon saw that the legacy was enriched by each audience, just as the students themselves were enriching an audience. As they created their own narratives of Austen’s accomplishments, her legacy, and the vital realities of her work, they came to understand the ongoing nature of Austen studies and, perhaps, quite a bit about the nature of literary criticism as well.

The first step was bringing some practical critical skills to their work. Although the seminar students never quite lost their sense of being overwhelmed as they put their exhibits together, they also wanted to make good use of that feeling. As noted above, many wanted exhibit visitors to experience the same sensation of awe and amazement that they themselves had first experienced. This desire itself began to break down classroom walls because students began seeing themselves as part of a larger community that could enjoy sharing their sense of wonder and puzzlement at the many ways in which Austen’s world still reverberates in twenty-first-century society. It also sometimes led to unrealistic expectations about what could fit into four to six exhibit cases. Student teams didn’t want to leave anything out! But accompanying the realization—albeit often at the eleventh hour—that all of their material wouldn’t fit into their assigned cases was the dawning realization that editing is as necessary to the successful presentation of an idea as accumulating.

Indeed, as their exhibit cases came together, students began to speak more and more cogently about the research process and what a good research project in the field of literature entails. Not only did they have to organize and present the material for their cases as they would if they were writing a paper, they had to act as true literary scholars as well. One Skidmore student, who admitted having signed up for the seminar simply to fulfill a requirement, spoke of his excitement at his realization that there were so many “radical” and different ways in which one could interpret Austen’s legacy. The critical essays that he’d read in class had helped him expand his ideas, but he saw the design of his exhibit case as a personal opportunity to move beyond the comfort zone in which Austen is sometimes viewed to enjoy instead being “able to look at her in all the different ways you can.” Interpreting Austen for others became what he called a “liberating” experience, one that opened his eyes to the possibility that literary criticism itself can be liberating when it re-examines received ideas. It should be noted that this same student continued to describe, with appreciation, the exhibit as a whole as a “haven” for everyone in the class as well as its visitors. In other words, it seemed to provide a safe place in which even “radical” questions about Austen could arise, because within that place it was obvious that Austen’s legacy is broad enough to support many different interpretations and responses. Thus the exhibit space gave students a useful model for the expansive, virtual space that literary criticism itself provides for discussion of an author’s works.

Collectively, too, the three exhibits, each with its differing approach to what was essentially the same material, mirrored why new research into familiar texts or new themes and theories constitute such important contributions to literary studies. Although the students reviewed the other groups’ exhibit guides, each seminar developed and presented its own view of Austen’s legacy: in 2004, rendering it chronologically; in 2006, dramatizing its ever-growing contemporary reverberations in light of its modest beginnings; in 2007, contrasting—but finding a home for—both “classic” and “radical” interpretations. Once again the students’ varied choices, following upon what students in the other seminars had done, demonstrated to them how literary criticism builds upon the past but continues to find fresh ideas to contribute to a never-ending conversation.

Students at Union reported several additional effects of spending so much time examining Austen’s legacy. Outfitting their exhibit manikins in matching Regency (“Emma”) and modern (“Clueless” or “Cher”) attire helped them to inhabit Austen’s world in unexpected ways (Fig. 7). Drawing upon their own wardrobes to outfit “Cher,” students reported being stunned to realize that the tale of the young woman who was their imaginary contemporary had roots stretching back to 1816. For another student, it was the Regency clothing that allowed her to enter more imaginatively into the novels. “I think the period clothing we had [was] the most memorable for me,” she wrote. “It strikes me now that in reading Austen, one really participates in the novel itself and becomes entirely immersed in Austen’s world. To be able to get up close to the clothing worn by people of the time makes it that much easier to imagine their reality.”

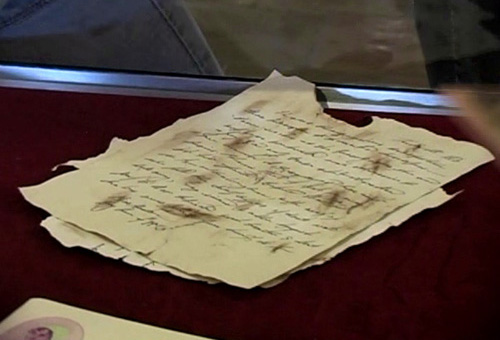

This trend among the students of developing a new relationship to Austen’s writings, characters, and times as they worked through their exhibit materials was common to all three seminars. Examining Austen’s legacy gave them, as one student expressed it, “a new appreciation for the complexity of her novels and for the wide range of material Austen manages to cover within the scope of what, on the surface, seems more like a ‘couple gets together’ kind of plot.” But it also made them intensely engaged with the original texts. By the close of the Union exhibit, for example, one student said that she looked upon the College’s first edition of Pride and Prejudice with new eyes, amazed that so much had evolved from such modest-looking beginnings. At Skidmore, a student who carefully burned the edges of facsimiles of some of Austen’s letters for her exhibit case (in order to dramatize Cassandra’s destruction of so much of her sister’s correspondence) said that doing so helped her to value—and to value the preservation of—such “collateral” literary resources all the more (Fig. 12).

On the other hand, the overwhelming amount of Austen-related “kitsch,” “gimcracks,” and “paraphernalia” (as the students variously described them) also made students more curious about Austen’s actual writings and social world. As one of them concluded, Austen’s influence is obvious, but you can only learn about Austen by reading and studying Austen herself.

Students described two additional kinds of learning beyond their typical classroom experience. First, they became as engaged with each other as they were with the Austen materials. Many students were daunted by the thought as well as the reality of working in small groups to come up with common themes and make decisions, but for the most part they loved it. Several of them noted that English majors, unlike those in other disciplines, rarely work on joint projects, so the exhibit project offered “a great opportunity to take a class outside the classroom.” One student said joyfully that it felt like being “in a glorified book club every day”; others relished the continual group conversations and interactions that combined to create “a different learning style that everyone got a lot from”; another liked the intensity of “many minds working together on an abstract level” to generate the “narratives” for their cases and the coherence for the exhibit.

But the happiest outcome for all seemed to be the fact that students with differing talents and interests—visual, textual, organizational, and otherwise—all collaborated effectively on the final product. “When put together in a group of other people,” said a student at Union, “we’re almost like bumper cars tapping against each other on certain issues. But I think that even with those different work ethics, we each contributed what we were meant to contribute . . . and to me, that is very special, and I was able to discover some very talented and creative persons: my classmates.”

The other kind of learning that students did in connection with the exhibits involved not just their classmates but the many kinds of visitors who came to see the displays and to interact with the students during the receptions that opened each exhibit (Fig. 14). English professors and librarians—those collaborators behind the scenes—were expected guests, but students were amazed by the numbers of friends, fellow students (including, at Union, entire sports teams), faculty, family members, and members of the general public who showed up at each opening event and during the course of each exhibit. College admissions tours were carefully routed to take in the exhibits, proving the adage that “Austen sells” and giving students further evidence of Austen’s popularity beyond the classroom.

More important, the constant exhibit traffic confirmed that the students’ work had value and meaning outside classroom walls. The crowded exhibit openings in particular gave students, as they described it, “a sense of pride,” and they “loved the way [the openings] brought all kinds of people on and off campus together.” The openings also put students on their professional mettle, as they were challenged to answer questions from visitors about the materials in their exhibit cases, about their exhibit themes, and about Austen herself.

A final question might be whether there is something special about Jane Austen that made the student exhibits so successful. Would this approach work for other writers as well? The answer is surely yes, as other student-created exhibits on authors as diverse as Bram Stoker and William Blake (at Skidmore and Union, respectively) have demonstrated. But we would nonetheless conclude that Austen is indeed special. The long history of her legacy, its many formats, its pervasiveness, its accessibility, and its appeal along a broad spectrum of potential exhibit visitors all ensure that students working with Austen’s legacy will find plenty to work with, plenty to say, and plenty of interested parties with whom they can share their insights. In the end, developing displays of Austen’s legacy equips students to become teachers—and there is no better way for them to “exhibit their learning” than that.

Acknowledgements

Photography by Jennifer Carr, Union College, and Skidmore College Media Services.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. The Novels of Jane Austen. Ed. R. W. Chapman. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1933-69. Harding, D. W. “Regulated Hatred: An Aspect of the Work of Jane Austen.” 1940. Twentieth Century Views of Jane Austen. Ed. Ian Watt. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice, 1963. 166-79. |