|

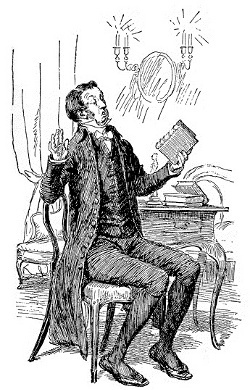

mr. Collins picks up James Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women (1766), and Lydia Bennet “gape[s],” interrupting with gossip about Meryton and the militia before, “with very monotonous solemnity, [he’s] read three pages (76-77). Lydia’s gape—whether interpreted as a mouth open wide, a stare of wonder, or a dramatic yawn—provides a comic response to a character defined from his first appearance as pompous and undiscerning. Mr. Collins has “started back” from the book offered to him, has “protested that he never read novels,” provoking us—the readers of the novel in which he figures—immediately to measure our difference from him. His heavy foolishness seems to be underscored here and then extended to the work he substitutes, to the Sermons themselves, whose own author inveighs against novel-reading: “We consider the general run of Novels as utterly unfit for you. Instruction they convey none” (1:149). In similar tones, Mr. Collins chastises Lydia’s inattention: “‘I have often observed how little young ladies are interested by books of a serious stamp, though written solely for their benefit. It amazes me, I confess;—for certainly, there can be nothing so advantageous to them as instruction.’” Marian E. Fowler’s description encapsulates that identity between Fordyce and his disciple: “Mr. Collins is Fordyce writ large” (57).

Much of the power of Austen’s fiction comes from the characters she creates, characters—as the proliferation of sequels attests—who seem able to step from the pages of her fiction into afterlives of their own. (Lost in Austen and Death Comes to Pemberley are merely two among the flood demonstrating this acknowledged truth.) Jane Austen herself, as her nephew tells us in his Memoir, “took a kind of parental interest in the beings whom she created,” passing on to her nephews and nieces what sounds much like gossip: “that Kitty Bennet was satisfactorily married to a clergyman near Pemberley, while Mary obtained nothing higher than one of her uncle Philips’ clerks, and was content to be considered a star in the society of Meriton” (Austen-Leigh 118-19). And, if we distrust such “traditionary” evidence, we have her own hand against her in the form of a letter to Cassandra in which, four months after the publication of Pride and Prejudice, she describes a visit to a London exhibition:

I was very well pleased—particularly (pray tell Fanny) with a small portrait of Mrs Bingley, excessively like her. I went in hopes of seeing one of her Sister, but there was no Mrs Darcy;—perhaps however, I may find her in the Great Exhibition . . . ;—Mrs Bingley’s is exactly herself, size, shaped face, features & sweetness; there never was a greater likeness. She is dressed in a white gown, with green ornaments, which convinces me of what I had always supposed, that green was a favourite colour with her. I dare say Mrs D. will be in Yellow. (24 May 1813)

Austen does return from the exhibitions, her disappointment is cheerfully colored by her surmises concerning Mr. Darcy’s behavior: “I am disappointed, for there was nothing like Mrs D. at either.—I can only imagine that Mr D. prizes any Picture of her too much to like it should be exposed to the public eye.—I can imagine he wd have that sort [of] feeling—that mixture of Love, Pride & Delicacy.” In this letter, the author’s certain knowledge of the characters she’s created is replaced by the satisfaction of a correct guess and further imagining of extra-textual behavior.

Austen’s characters seem to be available for what David A. Brewer has called “imaginative expansion,” at least partly because of the precision with which she’s imagined them. E. M. Forster long-ago contended that “all [Jane Austen’s] characters are round, or capable of rotundity, . . . ready for an extended life” (74-75). To put it another way, these characters, if not precisely embodied, are fully realized—and one of the ways Austen realizes her characters is to present them as readers. Throughout her fiction, Austen creates characters—like Mr. Collins—with certain formative reading experiences, experiences that seem to provide substance or dimension to fictional character. But if by presenting them as readers Austen increases the sense of the reality of her characters, she might simultaneously be said to undermine it. Readers of Pride and Prejudice reading about Fordyce’s Sermons, in measuring their own experience of reading Fordyce against Mr. Collins’s, or Lydia Bennet’s, may grant those characters a kind of contingent reality. But at the same time, readers imagining readers for one book (in this case the Sermons) may also become increasingly aware of the book in their own hands (in this case Pride and Prejudice)—the very pages of which signal the fictionality or immateriality of that world.

And as she peoples her fictions with these characters reading, Jane Austen does something yet more significant: she constructs the readers of those reading characters. In other words, Austen relies on, even invents, readers who not only have those same or similar formative experiences as her reading characters but who also simultaneously might recognize or at least respond to the shaping power of that reading. These shared reading experiences condition the understanding of plot, character, genre.

In Pride and Prejudice, then, Austen imagines or constructs a reader not only of Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women but also of his Addresses to Young Men and Hester Mulso Chapone’s Letters on the Improvement of the Mind (to which Mr. Darcy obliquely refers). Not only are there numerous verbal echoes between these texts and Austen’s novel, they also share thematic concerns (and, at least in the case of Chapone, have an impact on the structure of Austen’s novel). Although here I will only focus on the reading of Fordyce’s Sermons, and on only one aspect of that, I’m trying to move toward an understanding not only of how Austen creates readers but of what we might learn—or at least imagine—about her fictional process.

When Mr. Collins chooses Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women, he’s choosing a book with which Austen’s characters and readers were certain to be very familiar—and which they had probably read, and heard read, aloud. Jane Austen could rely on an extensive readership of conduct books. William St. Clair estimates that between 1785 and 1820, somewhere between 59,500 and 119,000 copies of conduct or advice books were sold to a population of some 320,000 families with incomes of at least £65 per year. “[I]t is evident,” he argues, “that a high proportion of the upper and middle classes must have owned copies of at least one advice book.” Moreover, “[m]any were sold in fine bindings, . . . an indication that they were meant to be kept and consulted.” According to St. Clair, Dr. Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters (1774) was the most frequently reprinted, with Chapone’s Letters and Fordyce’s Sermons following (505). So when Mary Bennet instructs her sisters and Miss Lucas that “‘Vanity and pride are different things, though the words are often used synonimously’” (21), readers might already have heard an echo of Fordyce: “pride and vanity are different things” (2:26).

By 1814, Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women had gone already through fourteen editions published in London alone. The Godmersham Park catalog—a catalog of the books at the Knight estate inherited by Edward Austen, at which his sister Jane visited and read—lists the eighth edition, published in 1775. The work serves as a touchstone in plays and novels of the period. In Sheridan’s The Rivals (1775), for example, Lydia Languish famously uses the Sermons to distract her guardian’s attention from the books that her maid has fetched from a circulating library. And in Clara Reeve’s 1791 novel, The School for Widows, the virtuous Mrs. Darnford reads Fordyce’s Sermons to her changers who—anticipating Lydia Bennet—“either gaped over them, or else talked aside as [she] was reading” (2:10). Mary Wollstonecraft, in her 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, discussed Fordyce’s Sermons second only to Rousseau in her “Animadversions on Some of the Writers who have Rendered Women Objects of Pity, Bordering on Contempt”: “Dr. Fordyce’s sermons have long made part of a young woman’s library; nay, girls at school are allowed to read them” (166). And Fordyce’s Sermons, of course, are available in the Bennet drawing-room among other books either currently read in or decorating that space.

Fordyce defines his principal motives for these Sermons in terms of a devotion to women and their role in society as well as for the pleasure of trying his own voice:

The author of the following Discourses was prompted to publish them, from an unfeigned regard for the Female Sex; from a fervent zeal for the best interests of society, on which he believes their dispositions and deportment will ever have a mighty influence; and, lastly, from a secret desire long felt of trying whether that style of preaching, which to him appears, upon the whole, adapted to an auditory above the vulgar rank, might succeed on a subject of this nature; nothing in the kind, that he knows of, having been endeavoured before, in any language. (1:iv)

Young women are significant to Fordyce primarily in terms of their social roles—defined of course by their relationships with men. As Janet Todd has pointed out, Fordyce made women “entirely contingent beings” (122), and that contingency informs every topic he addresses. Fourteen sermons cover the subjects of the importance of the female sex, modesty of apparel, female reserve, female virtue (over five sermons, during which he defines the accomplished woman), female piety (three sermons), good works, and female meekness (two sermons).

Indeed, to be fair to Lydia Bennet, the combination of his goals and stated means might cause some sinking of the spirits among readers and listeners:

To entertain the imagination principally, were a poor, and indeed a vicious aim in a preacher. To engage the heart, with a view to mend it, should be his grand ambition. Any farther than as it may prove some way or other subservient to that, entertainment should never be admitted into a Sermon. (1:iii)

Wollstonecraft demurs: “This is not the language of the heart, nor will ever reach it, though the ear may be tickled” (168). In fact, she objects to Fordyce’s style as much as to the substance of his sermons, describing his “mellifluous precepts” as “sentimental rant,” and objecting to “lover-like phrases of pumped up passion” as he addresses his readers (167, 168).

Austen’s use of Fordyce’s Sermons is more complex than her ironic view of Mr. Collins might indicate. Laura Vorachek identifies a “playful resistance” that stimulates Austen’s imagination (130) while Margaret Turnbull describes the novels as “gentle correctors” of Fordyce’s Sermons (50). Both Fordyce and Austen engage young women at what Sir Thomas Bertram defines as “their . . . most interesting time of life” (MP 36). Despite Fordyce’s protestations that “to be married is neither the one, nor the chief thing needful” (2:243), the Female Character he draws is modeled on the Virtuous Woman of Proverbs and certainly is designed for marriage. Introduced in the context of a courtship plot, Austen’s heroines move and grow toward marriage. Austen’s readers might well recognize three major areas in which Pride and Prejudice is in dialogue with Fordyce’s Sermons, all of which center on definitions of ideal female conduct: the attractions and dangers of the witty woman, the definition of the accomplished woman, and the depiction of the virtuous marriage and family.

Although those areas provide interesting insights into Austen’s novel, it’s the scene of reading in the Bennet drawing-room that I want to focus on here. Through the depiction of this scene, Austen makes us attend to Fordyce in a more specific way than we’re asked to, for instance, in The Rivals. In Sheridan’s play, the joke begins with the title of the Sermons and ends with the image of the pages used for curling Lydia Languish’s hair: to her maid’s hasty notice that “the hairdresser has torn away as far as Proper Pride,” Lydia tells her, “Never mind—open at Sobriety.” (Those sections don’t even exist!) But when Mr. Collins opens Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women and reads, both joke and effect are of a different and more complex order. The three pages he’s allowed would take—at a moderate pace—about three minutes to read. Which pages might those be? What do they cover? And what is “lost” by Lydia’s interruption?

Although this is a riddle with no certain answer, I want to hazard a guess. Mr. Collins’s methodical nature—as evidenced by his “very orderly” (117) proposal to Elizabeth—might, particularly at the commencement of a visit of almost two weeks, suggest a starting place. What could be more natural than that Mr. Collins, surrounded by his young cousins and their parents, would begin reading this fourteen-sermon collection at the beginning of the first volume, with Sermon I, “On the Importance of the Female Sex, especially the Younger Part”?

This sermon begins, like many of the others, with a verse from Paul’s letter to Timothy: “I will—that women adorn themselves in modest apparel, with shamefacedness and sobriety; not with broidered hair, or gold, or pearls, or costly array, but (which becometh women professing godliness) with good works” (1:3). Thus far in the novel, we’ve spent a good deal of time on the subject of adornment. Although, given Austen’s method, clothing hasn’t been the focus of attention, references thread their way through the text, setting scenes and defining characters and relationships early in the novel: recall Lizzy trimming a hat and her father’s provocative speculation as to whether Mr. Bingley will like it (6); Mr. Bingley’s blue coat (9); the elegance of Miss Bingley’s and Mrs. Hurst’s dresses, almost including Mrs. Bennet’s guess as to the cost of the lace on Mrs. Hurst’s gown (13); the importance of the milliner’s shop in Meryton (31); Elizabeth’s muddy petticoat (39); and, soon after Mr. Collins reads, the obtaining of shoe-roses from Meryton in preparation for the Netherfield Ball (98).

Far from rebuking such an interest in clothing, Fordyce begins by celebrating it. In two orotund paragraphs he collects scriptural instances of adornment to prove that “the Author of Nature . . . surely meant, that by beholding her with delight we might be led to copy her with care, and from contemplating the inferior orders of beauty rise to the admiration of that which is supreme” (1:4). In short, we can move from Lizzy’s bonnet to the Infinite in no time. God, according to Fordyce, provides the materials and inspires the genius that moulds them:

In saying this we are warranted by revelation itself, where we are expressly told, that “the spirit of the Lord filled Bezaleel, Aholiab,” and others, “with wisdom, and understanding, and knowledge, to devise and work all manner of curious and cunning works of the carver of wood, the cutter of stones, the jeweller, the engraver, the weaver, the embroiderer in blue and in purple, in scarlet and in fine linen.” What multitudes are daily employed and comfortably supported by these and such like ornamental arts, hardly any one is ignorant. (1:5)

At this point, near the bottom of the third page, there’s a break for a new paragraph, a pause for breath, which Lydia seizes upon to interject the news that her uncle “‘talks of turning away Richard, and if he does, Colonel Forster will hire him’” (77). Jane and Elizabeth “bid . . . [her] to hold her tongue,” but Mr. Collins is “much offended” and the reading is over.

So what did the Bennet family miss as a consequence of Lydia’s interruption? Beyond the contention that an appreciation of ornament might lead to an appreciation of God as supreme Maker, Fordyce defines women’s interest in dress as both essential to their beings as women and necessary to attracting a mate: “women may avail themselves of every decent attraction, that can lead to a state for which they were manifestly formed” so as not “by any neglect of their person . . . [to] disappoint the design of their creation” (1:6). The next words Mr. Collins would have read, then, had he not been interrupted, would have underscored his earlier “gallantry”—that the Bennet daughters, of whose beauty he “had heard much” though “ in this instance, fame had fallen short of the truth,” would “all in due time well disposed of in marriage” (72).

If Fordyce’s notion that the Bennet girls might “avail themselves of every decent attraction, that can lead to marriage” would, like Mr. Collins’s earlier attempt at compliment, be “not much to the taste of some of his hearers” (72), Fordyce’s next topic would be perhaps less welcome. His celebration of the female sex involves defining their “duty” (1:12) by imagining both the happiness of a parent in a daughter (1:14) and the importance of a daughter to a widowed mother (1:15-16), not the most tactful of pictures for the heir on whom Longbourn is entailed to present to Mrs. Bennet: “Something within [this soon-to-be widowed mother] whispers, you shall live to be the prop and comfort of her age, as you are now her companion and friend” (1:15). The comic infelicity of this topic is intensified by Mrs. Bennet’s response to Lizzy’s refusal of Mr. Collins: “‘I am sure I do not know who is to maintain you when your father is dead.—I shall not be able to keep you—and so I warn you’” (126). The early stages of Fordyce’s first sermon, then, highlight a Mr. Collins comically out of step with the Bennet family, as he is at Netherfield in his dances with Elizabeth, “awkward and solemn, . . . and often moving wrong without being aware of it” (101).

But the sermon Lydia interrupts might also have sounded a warning voice, as Fordyce imagines the obverse of the virtuous daughter in words that specifically forecast Lydia’s own plot: “When a daughter, it may be a favourite daughter, turns out unruly, foolish, wanton; when she disobeys her parents, disgraces her education, dishonours her sex . . . , what her parents . . . must necessarily suffer, we may conjecture, they alone can fee” (1:16-17). The Rev. Fordyce’s sentimental projection of the depth of parental suffering contrasts to the ironic specificity of Austen’s narrative judgment: Mrs. Bennet responds “exactly as might be expected; with tears and lamentations of regret, invectives against the villainous conduct of Wickham, and complaints of her own sufferings and ill usage” (316-17). Mr. Bennet acknowledges, “‘It has been my own doing, and I ought to feel it,’” but then admits, “‘I am not afraid of being overpowered by the impression. It will pass away soon enough’” (330).

Further, Fordyce’s language suggests Lydia’s trajectory in terms that emphasize the social even more than the moral:

The world, I know not how, overlooks in our sex a thousand irregularities, which it never forgives in yours; so that the honour and peace of a family are, in this view, much more dependant on the conduct of daughters than of sons; and one young lady going astray shall subject her relations to such discredit and distress, as the united good conduct of all her brothers and sisters, supposing them numerous, shall scarce ever be able to repair. (1:17)

This emphasis also gets picked up in the novel for ironic effect. We need only remember Elizabeth’s worry that that “every thing must sink under such a proof of family weakness, such an assurance of the deepest disgrace” (306); she is alive to “the humiliation, the misery, [Lydia] was bringing on them all” (307).

Though Fordyce’s introductory sermon emphasizes virtues such as modesty, meekness, prudence, piety, these seem oddly secondary to the erotic powers of the female body. Fordyce flatters his young listeners that “[t]here is in female youth an attraction, which every man of the least sensibility must perceive. If assisted by beauty, it becomes in the first impression irresistible” (1:18). In the picture of “conjugal felicity or domestic comfort” represented by the Bennets (262), Austen undercuts the flattering image of the attractions of youth that Fordyce (or Mr. Collins) celebrates. That irresistible first impression can turn a man of sensibility, like Mr. Bennet, “captivated by youth and beauty, and that appearance of good humour, which youth and beauty generally give,” into a “true philosopher . . . deriv[ing] benefit from” his wife’s “ignorance and folly” (262). Fordyce acknowledges that a woman, “if she be so minded, has still the power of plaguing her partner out of every real enjoyment” (1:32-33), but he celebrates the effect of the society of women of virtue and understanding on man:

It produces a polish more perfect, and more pleasing . . . , the result of gentler feelings, and a more elegant humanity. . . . The Gentleman, the Man of worth, the Christian, will all melt insensibly and sweetly into one another. How agreeable the composition! (1:23-24)

Mr. and Mrs. Bennet sit before Mr. Collins and before us as a potent counterexample to Fordyce’s rose-scented idyll.

This aromatic image wafts a reader toward the bouquet Mr. Collins seems prepared to tender at the end of his reading, Fordyce’s highly-colored depiction of the wife and mother, the climax of Fordyce’s first sermon. I’m suggesting, of course, that Mr. Collins begins reading aloud this very sermon as flattering to the female sex, as edifying for the girls from among whom he’ll choose a wife, and as a wildly inappropriate compliment to both Mr. and Mrs. Bennet. Listen to the Rev. Fordyce’s conclusion—the point toward which Mr. Collins assuredly tends. Certainly here we’re meant to apply his description of the maternal ideal not only to whichever lucky Miss Bennet will become Mrs. Collins but also to Mrs. Bennet, the mother surrounded by daughters and husband:

But lastly, let us suppose you Mothers; a character which, in due time, many of you will sustain. How does your importance rise! A few years elapsed, and I please myself with the prospect of seeing you, my honoured auditress, surrounded with a family of your own, dividing with the partner of your heart the anxious, yet delightful labour, of training your common offspring to virtue and society, to religion and immortality; while, by thus dividing it, you leave him more at leisure to plan and provide for you all; a task, which he prosecutes with tenfold alacrity, when he reflects on the beloved objects of it, and finds all his toils both soothed and rewarded by the wisdom and sweetness of your deportment to him and to his children. I think I behold you, while he is otherwise necessarily engaged, casting your fond maternal regards round and round through the pretty smiling circle; not barely to supply their bodily wants, but chiefly to watch the gradual openings of their minds, and to study the turns of their various tempers, that you may “teach the young idea how to shoot,” and lead their passions by taking hold of their hearts. I admire the happy mixture of affection and skill which you display in assisting Nature, not forcing her; in directing the understanding, not hurrying it; in exercising without wearying the memory, and in moulding the behaviour without constraint. I observe you prudently overlooking a thousand childish follies. You forgive any thing but falshood or obstinacy: you commend as often as you can: you reprove only when you must; and then you do it to purpose, with moderation and temper, but with solemnity and firmness, till you have carried your point. You are at pains to excite honest emulation: you take care to avoid every appearance of partiality; to convince your dear charge, that they are all dear to you, that superior merit alone can entitle to superior favour, that you will deny to none of them what is proper, but that the kindest and most submissive will be always preferred. . . . Those lovely plants which you have reared I see spreading, and still spreading, from house to house, from family to family, with a rich increase of fruit. I see you diffusing virtue and happiness through the human race; I see generations yet unborn rising up to call you blessed! (1:34-37)

The reader of Fordyce and Austen can contrast the Fordycean ideal and the Bennet real. For the reader familiar with Fordyce’s Sermons, surely a large portion of her readership, Austen comically and tellingly exploits the difference between Fordyce’s ideal father and Mr. Bennet, between his exemplary instructress and Mrs. Bennet: the “tenfold alacrity” with which Mr. Bennet is expected to provide for his offspring; the “anxious . . . labour” of Mrs. Bennet to educate her daughters, to watch the “gradual openings of their minds”; her prudence and impartiality. And the image of the spreading plants, though, as Mary Bennet might say, “‘not wholly new, yet . . . is well expressed’” (71).

If this speculation as to Mr. Collins’s intended compliment seems a bit tenuous, we might remember the dinner conversation that takes place immediately before this scene. There Mr. Collins acknowledges that “‘those little delicate compliments which are always acceptable to ladies’” that he offers for Lady Catherine “‘arise chiefly from what is passing at the time, . . .though I sometimes amuse myself with suggesting and arranging such little elegant compliments as may be adapted to ordinary occasions’” (76). It’s not much of a stretch to imagine that a visit to a family of young ladies, into which he intends to marry, might call forth a similar effort. In this case, however, his labors result in a fruitless attempt to tickle their ears.

Mr. Collins may admit to flattery as a tactic. Fordyce does not. But while Fordyce claims to have “rendered the plain voice of Truth acceptable amongst those who are daily tempted by the siren-song of Flattery” (1:v-vi),Wollstonecraft charges him with the inverse: “If women be ever allowed to walk without leading-strings, why must they be cajoled into virtue by artful flattery and sexual compliments?—Speak to them the language of truth and soberness, and away with the lullaby strains of condescending endearment” (168). Elizabeth Bennet’s later plea to Mr. Collins—“‘Do not consider me now as an elegant female intending to plague you, but as a rational creature speaking the truth from her heart’” (122)—seems born of the same response.

At the end of her discussion of Fordyce’s Sermons, Mary Wollstonecraft remarks, “As these volumes are so frequently put into the hands of young people, I have taken more notice of them than, strictly speaking, they deserve; but as they have contributed to vitiate the taste, and enervate the understanding of many of my fellow-creatures, I could not pass them silently over” (170). Jane Austen doesn’t seem to be interested in a simple acceptance or rejection of the ideals articulated by conduct books. In her appropriation of Fordyce, the conduct book is a comedic tactic: partly useful for highlighting and sharpening thematic concerns (including issues of gender), partly for developing Mr. Collins’s character—as Turnbull puts it, “the walking, constantly talking embodiment of a certain tone in Sermons to Young Women, that of a self-satisfied rhetorician with little understanding of either women or the grace of God” (42). The joke defined around the actual reading of the sermons, however, is more complex and happens—if it does happen—in the gaps, in the space of a sentence or two, unfolding in the consciousness of the reader rather than on the page. It seems to validate Austen’s claim that she doesn’t write for “dull elves” but for readers with some ingenuity. The comedy and the expansion of character are, to pick up Keats’s phrase, “uncontaminated and unobtrusive.”

Earlier I claimed that examining this use of Fordyce might provide some insight into Austen’s method of creating fiction. Cassandra’s notes on the composition of the novels provide only a bit of guidance. “First Impressions begun in Oct 1796,” she writes. “Finished in Augt 1797. Published afterwards, with alterations & contractions under the Title of Pride & Prejudice” (qtd. in PP xxiii). First Impressions was offered to Cadell on November 1, 1797; it was declined. There is much critical disagreement both about when Jane Austen might have revised her novel and about how extensive those revisions might have been.

In his Cambridge University Press edition, Pat Rogers suggests that the reference to Fordyce is traceable to the concerns of the 1790s. Are the traces of Fordyce and Chapone in Pride and Prejudice, then, mere remnants of what might have been a more extensive and more obvious use in First Impressions (akin to the incorporation of the Gothic in Northanger Abbey)? We might guess that after reflecting a heightened concern with conduct and interest in conduct manuals in the 1790s, Jane Austen began subsequently to eliminate and submerge the most overt references to these conduct books. The question of when and how this transformation occurred—how Austen “lopt & cropt” (29 January 1813) her way to Pride and Prejudice—is impossible to answer. But we can see that Austen, rather than using these materials in any discursive or even overt way, transforms and incorporates them into the fabric of her fiction. Margaret Anne Doody has described Austen’s juvenilia as “rough, violent, sexy, joky . . . , sparkl[ing] with knowingness” (98). That knowingness in the juvenilia sports with the literary texts that the young Jane Austen and the members of her family are reading together. Perhaps what we see in Pride and Prejudice is the remains of this wilder playfulness, now incorporated into the sparkling sobriety of Jane Austen’s mature vision.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1997. _____. Mansfield Park. Ed. John Wiltshire. Cambridge: CUP, 2005. _____. Pride and Prejudice. Ed. Pat Rogers. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. Austen-Leigh, J. E. A Memoir of Jane Austen. A Memoir of Jane Austen and Other Family Recollections. Ed. Kathryn Sutherland. Oxford: OUP, 2002. 1-134. Brewer, David A. The Afterlife of Character, 1726-1825. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2005. Fordyce, James. Sermons to Young Women. Introd. Susan Allen Ford. 10th ed. 1786. Southampton: Chawton House P, 2012. Forster, E. M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt, 1927. Fowler, Marion E. “The Feminist Bias of Pride and Prejudice.” Dalhousie Review 57 (1977): 47-64. Godmersham Park Library Catalogue [1818-c. 1840]. 2 vols. Bound ms. Chawton House Library, Chawton, UK. Reeve, Clara. The School for Widows. 3 vols. London, 1791. St. Clair, William. “Women: The Evidence of the Advice Books.” The Godwins and the Shelleys: The Biography of a Family. London: Faber, 1989. 504-11. Sheridan, Richard Brinsley. The Rivals. 1775. The Dramatic Works of Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Ed. Cecil Price. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1973. Turnbull, Margaret. “Jane Austen and James Fordyce.” Sensibilities 34 (2007): 34-57. Vorachek, Laura. “Intertextuality and Ideology: Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and James Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women.” New Windows on a Woman’s World: Essays for Jocelyn Harris. Ed. Colin Gibson and Lisa Marr. Otago Studies in English 9. Vol. 2. Dunedin, NZ: Dept. of English, University of Otago, 2005. 129-37. Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Men and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Ed. Janet Todd. Oxford: OUP, 1993.

|