|

Edward Austen’s inheritance of Chawton and Godmersham from his benefactor Thomas Knight is well documented. Thomas Knight and his new bride, Catherine, were on a tour of their recently inherited estates. At Steventon, they visited their distant cousin, the Rev. George Austen and his family. The event is immortalized in the famous silhouette by English artist William Wellings that hangs at Chawton House. Taking a fancy to Jane’s twelve-year-old brother, they took him on the tour of these estates. Whether he travelled as far as Godmersham on this occasion is not known, but he would have visited Chawton and Winchester. When Thomas and Catherine failed to produce any heirs, they officially adopted the sixteen-year-old Edward in 1783 (Nokes 72-73). It is a little known fact that for over one hundred sixty years, the Knight family were also owners of a third estate in addition to Chawton and Godmersham: Abbots Barton and Abbey Farm, the former Hyde Abbey’s lands in Winchester, which included the burial site of King Alfred.

The key to understanding how Thomas Knight came to own land in Winchester, the complexities of Edward’s inheritance, and why he almost lost Chawton, can be found in the church of St. Nicholas in Chawton, in whose graveyard Jane Austen’s mother and sister are buried. Jane’s knowledge of the issues of entail displayed in Pride and Prejudice emanates from this family history. When periodically faced with a lack of a male heir, the Knight dynasty perpetuated the family name and kept estates intact by importing heirs from among remote cousins, one of whom was Jane’s brother, Edward.

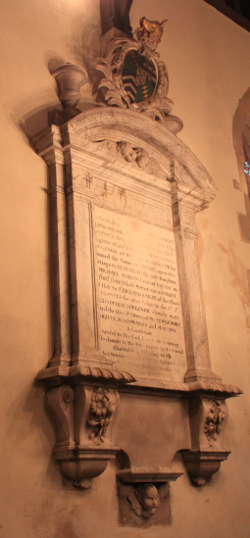

The church is a little different from Jane’s day when the Rev. John Hinton was rector; at that time, the west end of the church was in a ruinous condition, and the rotten timbers in the tower threatened the bells. In 1838 Edward Knight provided the rector, his son Charles Bridges Knight, the desperately needed finance for rebuilding this part of the church. In 1871, during further restoration, the nave and its contents were destroyed by fire (Austen-Leigh and Knight 60-61). Some of the memorials dedicated to the former owners of Chawton survived, including the semi-recumbent effigy to Sir Richard Knight (the last of the direct Knight line), which dates from 1679. Another survival, a stone tablet to William Woodward Knight, outlines the family history:

Lyes the body of William Woodward Knight the only son of Edward Woodward of Fosters in Surrey by Elizabeth the eldest daughter of and coheir to Christopher Lewkenor of West Dean Sussex who assumed the name Knight upon his marriage to Elizabeth only daughter of Michael Martin gent of Ensome Oxfordshire (whose mother was a Knight and heir to Sir Richard Knight of this place) by Frances the other coheir to Sir Christopher Lewkenor, whereby were united the several estates of the Lewkenors, Knights, Woodwards and Martins.1

At Chawton House itself, the magnificent portraits of many of the former owners of Chawton, Abbots Barton in Winchester and Godmersham Park can be seen2 The owners of the three estates were affluent landowners and many served as members of Parliament. Financially savvy gentry expanded their estates by carefully considered marriages between important local families and sometimes through the consolidation of an estate by means of land exchanges. The story of land acquisition, inheritance, and why Edward was able to re-house his family at Chawton is told on the stone tablet.

The story of the Knight family’s involvement in Winchester begins with the mother-in-law of Sir John Lewkenor, Anne Mynne. Sir John was the nephew of Sir Christopher Lewkenor and a cousin of William Woodward and Elizabeth Martin. Anne’s husband, George Mynne of Woodcote Park, Epsom, was described as a merchant, draper, clothier, royal servant, politician, ironmaster, moneylender, clerk in Chancery, and extortionist (Malden 271-78).3 Following George’s death in 1648, his trustees managed his estate on behalf of his widow, Anne. In 1649 Anne purchased the reversionary interest of the Manor of Steventon in Hampshire from Thomas Brocas (Page 171-74). In 1650 she purchased the manor belonging to Edward Darcy in Epsom.

So how did the Abbey Farm (the home farm and site of Hyde Abbey) and Abbots Barton (the grange farm) end up in the hands of the owners of Chawton?4 After Hyde Abbey was dissolved in 1538 by Henry VIII, Hyde Abbey’s farms were separated and sold to different owners. In 1650 Anne Mynne purchased Abbots Barton from the financially-ruined owner. On Anne Mynne’s death in 1663 her estates passed to her daughters: Elizabeth (wife of Richard Evelyn5) and Lady Anne (wife of Sir John Lewkenor of West Dean, Sussex). The Epsom estate passed to Elizabeth, Abbots Barton to Lady Anne, and Steventon was shared between them. Under the law at that time, Sir John was seen as the owner of all Lady Anne’s wealth and property. Lady Anne was well-connected. Her husband’s uncle was Sir Christopher Lewkenor, MP for Midhurst (1628) and Recorder of Chichester (1640). Sir John died in 1669 (aged 46) and Lady Anne (then aged 35), as was common for a young widow, soon married again. Her second husband, Sir William Morley of Halnaker, Sussex, was also a rich and respected member of the gentry (Page 171-74).6 (The family trees of the Lewkenors and Knights are given in the Appendix.7)

When Lady Anne died in 1704, all her estates, including Abbots Barton, passed to her son John, who, like his father, also served as MP for Midhurst. John died in 1706 with no legitimate heirs, and Abbots Barton passed to Elizabeth Martin, a distant cousin, through her parents Michael and Frances (née Lewkenor). Elizabeth already owned extensive property, inheriting lands at Chawton in 1702 after the deaths of her brothers, Richard and Christopher. The Knight family had owned Chawton from 1524 when William Knight had taken on the lease of the manor place and farm. When his descendent, Sir Richard Knight died in 1679 without heirs, the estate passed to the grandson of his aunt, Dorothy. (See Appendix, Table 2.) The eldest grandson, Elizabeth’s brother Richard, died of smallpox in 1687 while at Oxford. Their brother, Christopher, also died young.

Elizabeth Martin was a strong woman with a sense of duty and took an active part in managing her estates (Austen-Leigh and Knight 124). Her detailed accounts have survived at Hampshire Record Office.8 As a requirement of her inheritance, Elizabeth changed her name to Knight as her brothers in their turn had done. When Elizabeth married her cousin William Woodward (son of Elizabeth Lewkenor, her mother’s sister), he too changed his name to Knight, thus perpetuating the Knight family name even though the last direct heir had died in 1679 (Burke 442-44; Austen-Leigh and Knight 122-24, 127-29). Four years after William Knight (né Woodward) died in 1721, Elizabeth married Bulstrode Peachey, who was at one time MP for Midhurst. Her second husband also relinquished his family name, becoming known as Peachey Knight; such was the power of the inheritance conditions.

The marriage settlement between Elizabeth Knight and Bulstrode Peachey was used to protect the rights of Elizabeth’s heirs once Bulstrode had rights over his wife’s property.9 If such an agreement had not been reached, the future of Chawton and Abbots Barton would have been very different. Elizabeth was not entirely happy with the settlement, but “she accepted for the sake of peace.”10 There is some doubt whether Peachey was happy to go through the legal process to separate out the two interests to ensure the profits from Elizabeth’s estates went to her and for her lands to be passed to her heirs rather than to his family. In a somewhat complaining tone, Bulstrode noted in his will that he had laid out “considerable sums of money in repairs and lasting improvement of Mrs Knight’s separate estate and of her other estates all with repairs and improvements.” Bulstrode died in 1735, and as his brother had pre-deceased him, his lands were left to his nephew Sir John Peachey for his life.11

Elizabeth died in 1737, leaving no surviving heirs and no immediate relatives. On her memorial stone in St. Nicholas Church, Chawton, the owner of Abbots Barton is described thus:

She lived with affectionate Tenderness to her Husbands, a courteous Affability to her Friends and charitable Liberality to the Poor. In the true Faith & Fear of God. In a constant Practice of Piety, a christian Charity: and an Example of the true Religion, and Virtue.

Before she died, Elizabeth’s legal advisors constructed a clearly defined entail which was to determine the future of the two estates for generations to come. Under English law, property inheritance followed a well-defined pathway: father (the current entail) to son (the new entail), and then to the heir of the son’s body (future entail). Entails were added or refreshed in each generation. The widow inherited for her lifetime. The current landowner had a life interest being either a “tenant for life” or “tenant in possession.” Fee-tail limited inheritance of the estate to a specified heir or heirs by means of a settlement or will. Usually inheritance was restricted to legitimate male heirs described as “of the body, and so excluded adopted children. Males took precedence over females (as is common in royal lineage). Strict entail in tail-male barred an estate passing to more distant relatives such as cousins. The line could not pass through the mother or a wife.

Elizabeth had no children or close relatives, and so her two Hampshire estates passed in tail-male to a distant relative, in this case a second cousin related three generations back. The will set up an entail naming Thomas May of Godmersham, William Lloyd of Newbury, and the Rev. John Hinton of Chawton and their descendants successively as the heirs:

Manors of Lordships, messuages, farms, land, tenements, hereditaments and premises were given to the use of Thomas May of Godmersham (who hath since in pursuance of a will, taken upon himself to be called Thomas Knight) for his life without impeachment of waste, remainder to the use of William Guidott, John Baker and Edward Munford and their heirs during the life of Thomas (May) Knight in trust to preserve the contingent remainder and after the death of Thomas Knight to use of the first and every other son of the body of Thomas Knight lawfully to be begotten successively in tail-male remainder to the use of William Lloyd of Newberry, gent for his life with the provision for supporting the contingent remainder and after his decease to use of the first and every other son of his body lawfully to be begotten successively in tail-male. Remainder to John Hinton of Chawton, clerk for his life without impeachment of waste with like limitation to preserve the contingent remainder and after his decease to use of the first and every other son of his body lawfully to be begotten successively in tail-male. Remainder to the right heirs of the testatrix Elizabeth forever.12

A proviso or condition was that Thomas May, his sons, and the heirs of their respective bodies who came into possession of the premises, were to change their surnames to Knight.

Thomas was the son of Anne May and William Broadnax. His mother’s aunt Mary and her husband, Sir Christopher Lewkenor, were the grandparents of both Elizabeth Knight and her first husband, William Woodward. Thomas Knight, the new owner of Chawton and Abbots Barton, was well-respected, highly educated, and active in politics. He was educated at Balliol College, Oxford, studied law, acted as High Sherriff of Kent, and became MP for Canterbury. Born a Broadnax, Thomas had changed his name to May in 1727 after inheriting the estates of Sir Thomas May of Rawmere, near West Dean in Sussex. Thomas married Jane Monk in 1729: they had many children, but only five survived to adulthood, a son and four daughters, who died spinsters. On Elizabeth’s death, Thomas once again was compelled to change his name as a condition of inheritance―this time to Knight. Each change of name required a private and expensive Act of Parliament, and one MP commented, “This gentleman gives us so much trouble that the best way would be to pass an Act for him to use whatever name he pleases” (qtd. in Nokes 34).

Managing the Chawton and Winchester estates, which were a three-days ride away from Godmersham, was difficult for Thomas Knight and his steward Edward Randall. Any consolidation of the scattered lands in Hampshire, Surrey, and Sussex inherited from distant relatives led to more efficient and cost-effective estate management. After his inheritance of the Knight estates, Thomas Knight took the opportunity to expand and consolidate his landholdings. He sold Rawmere, the ancestral home of the Mays, and in 1744 he exchanged some of Lewkenor’s West Dean estate with land close to Chawton, now in the ownership of Sir John Peachey. As the two estates had almost identical values, Sir John Peachey and Thomas Knight for “their mutual convenience and accommodation and for the improvement of their several estates in two counties have proposed to make exchange.”13

Hampshire was traditionally a sheep and corn area. Although only sixteen miles away, the Winchester estate’s landscape was different from Chawton. The ideal farm in Hampshire, as Charles Vancouver’s General View of the Agriculture of Hampshire 1810 suggested, allowed for mixed agriculture, utilizing both downland and water meadows: “hence rises the favourite idea among the down farmers, that no farm can be advantageously disposed for the general circumstances of that country, unless it has water-meadow at one end, and maiden down at the other” (Vancouver 78). The meadows were flooded weekly between late November or early December to the beginning of March, thus protecting the land from frosts and allowing the nutrients in the water to fertilize the land. The flooding of the meadows produced an early growth of young succulent grass, facilitating early lambing and increasing the viability of larger flocks, both of which increased the farmer’s income.

The landscape, however, posed challenges for a distant landowner like Thomas Knight and his steward Randall. Like Chawton, the Winchester estate was let out to tenants. Water meadows needed careful maintenance to keep them flowing and regular visits to ensure land was not flooded by irresponsible tenants of neighbouring properties. There was a long history of disputes between previous owners and tenants. Randall was responsible for Abbots Barton Farm and for carrying out negotiations with the owner of Hyde Abbey Farm (the fourth Duke of Bedford) over the operation of the water meadows, whose functioning affected both estates. In 1738, Thomas Knight attended a meeting in Winchester of owners and tenants to resolve on-going matters and successfully negotiated a solution. In 1767, the Winchester estate was extended with the purchase of Hyde Abbey Farm for £5,000 from the Duke of Bedford, who was experiencing financial problems on his London urban estates. The former Hyde Abbey farms were reunited for the first time in 230 years under Thomas Knight’s ownership (Grover 80-86).

When Thomas (Broadnax May) Knight died in 1781, his son, Thomas, inherited the three estates. The younger Thomas did not appear to have such a concern for the Winchester estate or indeed history. In 1785, he sold the site of Hyde Abbey, the burial place of the Saxon King Alfred the Great, his wife, and son to the County for the Bridewell—a House of Correction.14 He also sold other land nearby. To be fair, these plots were not productive, so there was no financial benefit in retaining them (Grover 103, 119).

Thomas Knight died in 1794. In his will he left Godmersham and his other estates, which included Abbots Barton, to his widow, Catherine, for her life and confirmed Edward Austen as his adopted heir. He added the clause that if Edward did not have any children, then the estates should pass to Edward’s brothers in succession. Thomas Knight’s estates had been tied up in trust between William Deedes (the elder and younger) and Nicholas Cage, of whom only William Deedes (the younger), was still alive.15 Four years after her husband’s death, Catherine decided that the estate was better passed over to Edward and his family to run, rather than for him to wait for her to die before inheriting.

Catherine Knight out of her love and affection for Edward Austen and in order to advance him to their present possession of the estates which were settled on him and his issue in remainder under the will agreed to convey all the estates unto and to the use of Edward Austen during the joint lives of him and her Catherine Knight subject to a rent charge or clear annual sum of £2,000 clear of all deductions and taxes to be reserved and made passable.16

Jane Austen did not hold back in her opinions of her brother’s benefactor, and in a letter to Cassandra in 1798 she comments:

Mrs Knights giving up the Godmersham Estate to Edward was no such prodigious act of Generosity after all it seems, for she has reserved herself an income out of it still;—this ought to be known, that her conduct may not be over-rated.—I rather think Edward shews the most Magnanimity of the two, in accepting her Resignation with such Incumbrances. (8 January 1799).

Jane Austen’s irony here is complex. All the risks of the income falling short had passed to Edward, together with the burden of managing the estate. The income from Godmersham and Chawton are estimated at £5,000 and £10,000 a year respectively (Hildebrand). Assuming that these figures were gross of tax and management costs, Mrs. Knight’s reserved income would have been large. The over-generous size of Mrs. Knight’s income can be compared to that of nobility (averaging £8,000 a year) and landowning baronets and knights (upwards of £1,000 a year) (Heyyck 48-49). In Pride and Prejudice, Fitzwilliam Darcy has an annual income of £10,000; Charles Bingley receives a return of 4-5% on his inherited property of £100,000; and an average clerical living earns well below £1,000 a year.17

Catherine Knight moved to Canterbury, leaving Edward the pleasure and worries of Godmersham Park and the stewardship of Chawton and Winchester estates. Edward’s stewardship of Abbots Barton lasted for thirteen years before the decision was made to sell this more remote part of the Knight lands. Through the sale, Edward was able to release capital to meet financial demands—for example, improvements to Godmersham—and to cut running costs by selling land that was expensive and difficult to maintain. In 1811 the Knight family’s ownership of the Winchester estate came to an end when Abbots Barton Farm, extending to 501 acres of uplands and water meadows, was sold for £33,670 to William Simonds, a local farmer of St. Cross, Winchester (Grover 103).

When Mrs. Knight died in 1812, Edward—as a long standing condition of the inheritance—changed his name to Knight. In a letter of 6 January 1812 to Jane Austen, Edward’s daughter Fanny comments, “We are therefore all Knights instead of dear old Austens. How I hate it!!!!!!” (qtd. in Nokes 395). After 133 years during which Chawton was transferred from one distant relative to another, the Knight name survived to become firmly established in one family—the Austens. But like Abbots Barton, Godmersham was eventually sold, and only Chawton remains in Knight hands.

The history of the three estates that formed Edward’s inheritance, with all the characters and their legal wrangles, would have been common knowledge in the Austen family. With the challenge to Edward’s inheritance, the provenance of his lands would have been the prime topic of conversation over several years. It is not therefore surprising that inheritance and land law are significant and recurring themes in Jane Austen’s novels.

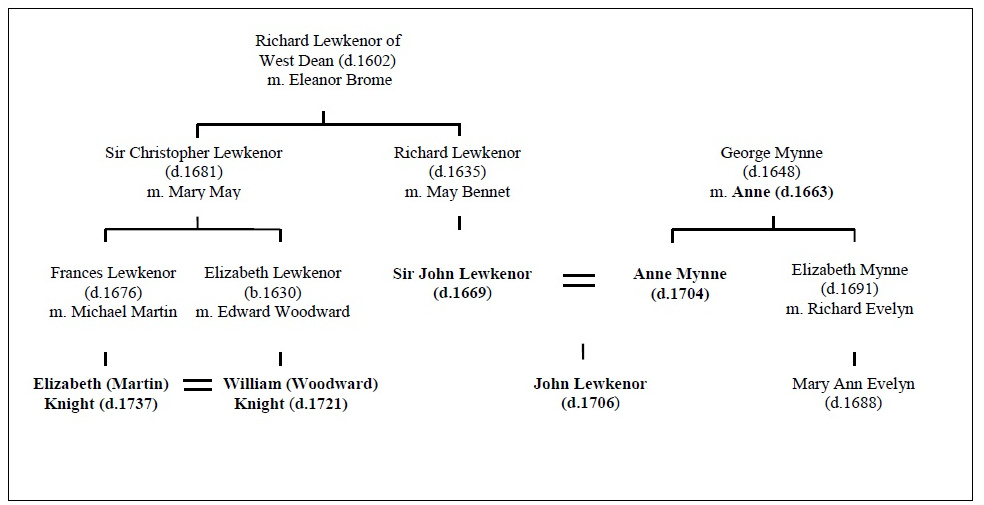

APPENDIX: TABLE 1: The Lewkenors, Martins, Woodwards, and Mynnes

Sources: Burke (1835) and Austen-Leigh and Knight (1911). Those who inherited Chawton or Abbots Barton are in bold.

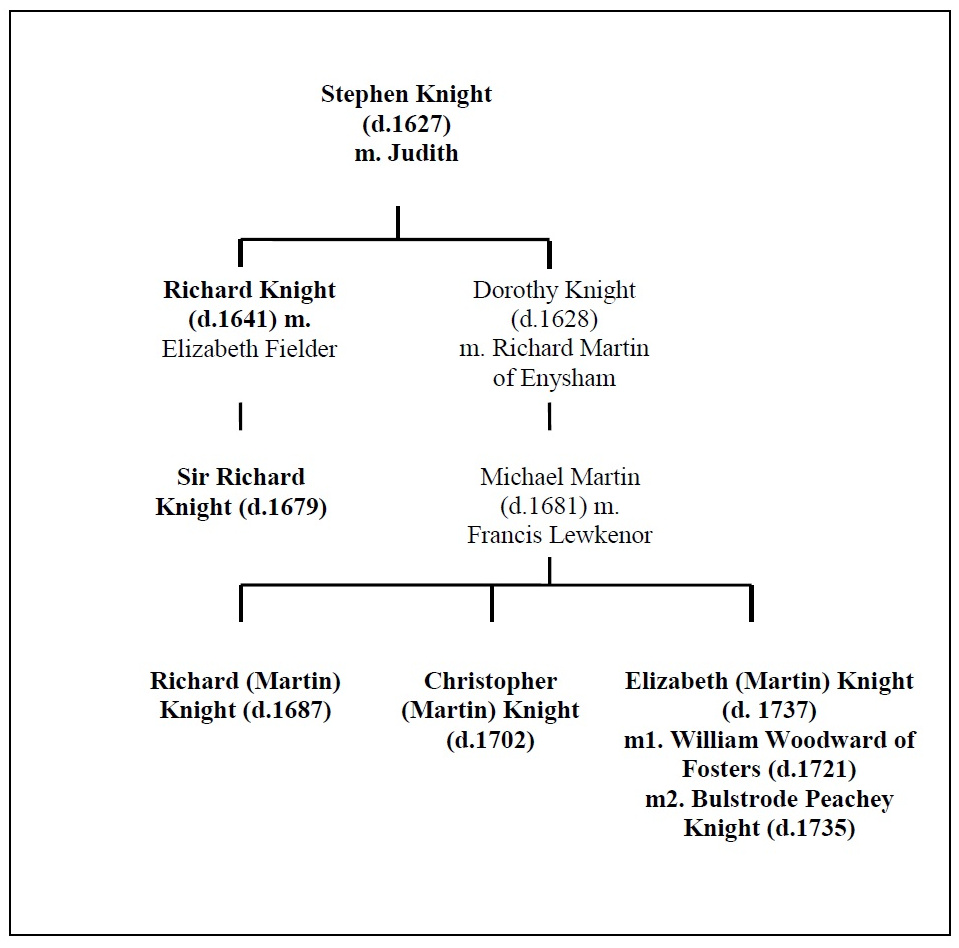

TABLE 2: Knights of Chawton Family Tree

Sources: Burke (1835) and Austen-Leigh and Knight (1911). Those who inherited Chawton are in bold.

Notes

1. The exact format on the stone can be found in the appendix to Austen-Leigh and Knight’s Chawton Manor.

2. Black and white images can be found in Austen-Leigh and Knight, available online at https://archive.org/details/chawtonmanoritso00austuoft. With the kind permission of Richard Knight,colored images are found in Grover’s Hyde: From Dissolution to Victorian Suburb.

3. A history is given at http://www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/MynneG.html.

4. Two archives in the care of Hampshire Record Office (HRO), Winchester, contain a wealth of documents that trace the ownership of the Chawton and Abbots Barton estates: Knights of Chawton archive HRO:39M89/E/ and Barrow Simonds of Winchester papers HRO:13M85W/. The history of Abbots Barton and the Knights’ involvement is detailed in Grover, Chapters 3 and 4. (Extracts of the book can be found at http://www.victorianheritagepress.co.uk.)

5. Richard’s brother was the famous diarist John Evelyn, a contemporary of Samuel Pepys.

6. Also at http://www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/MynneG.html.

7. Extended family trees can be found in Austen-Leigh and Knight: Knights (72), Lewkenors (96), Mays (130), and Austens (150).

8. HRO:39M89/E/B614.

9. HRO:39M89/E/B615.

10. HRO:39M89/E/T/17.

11. HRO:39M89/E/B614/8,9.

12. HRO:13M85W/37. John Hinton was rector at St, Nicholas, Chawton, and died 1802.

13. HRO:39M89/E/T23/18 and HRO:13M85W/29.

14. With the successful identification of King Richard III’s skeleton, focus has shifted to the church of St. Bartholomew in Hyde, where it is thought that bones, possibly relocated when the Bridewell was built on Thomas Knight’s former land, might belong to King Alfred and his family.

15. Both Lewis Cage and William Deedes were brothers-in-law to Edward Austen by their marriages to the daughters of Sir Brook Bridges. Jane Austen and her sister, Cassandra, often met Mary Deedes and Fanny Cage when they stayed at Godmersham.

16. HRO:13M85W/38.

17. See Marilyn Francus for detailed information on the income and wealth of men and women in Jane Austen’s novels.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1995. Austen-Leigh, William, and Montagu Knight. Chawton Manor and Its Owners; A Family History. London: Smith, 1911. Burke, John. History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 1. London, 1835. Francus, Marilyn. “Jane Austen, Pound for Pound.” Persuasions On-Line 33.1 (Win. 2012). Grover, Christine. Hyde: From Dissolution to Victorian Suburb. Winchester: Victorian Heritage Press, 2012. Heyck, Thomas William. The Peoples of the British Isles: A New History. Volume 2: From 1688 to 1870. 3rd ed. Chicago: Lyceum, 2008. Hildebrand, Enid G. “Jane Austen and the Law.” Persuasions 4 (1982): 34-41. Malden, H. E. “Parishes: Epsom.” A History of the County of Surrey. Vol. 3. London: Constable, 1911. 271-78. Nokes, Davis. Jane Austen. A Life. London: Fourth Estate, 1997. Page, William, ed. “Parishes: Steventon.” A History of the County of Hampshire. Vol. 4. London: Constable, 1911. 171-74. Vancouver, Charles. General View of the Agriculture of Hampshire Including the Isle of Wight. London, 1810.

|