|

in the autumn of 1814, disappointed that Mansfield Park had not been reviewed in the press, Jane Austen began collecting feedback on her new novel from family and friends. Some opinions she copied from family letters while others were reported to her or given in person. She tidily arranged this private reader response under the heading “Opinions of Mansfield Park.” Critics have aptly characterized some of this reader feedback as “tepid” (e.g., Southam 223), but among the thirty-eight entries, we can also see striking enthusiasm for the portion of the novel set in the bustling naval town of Portsmouth. “Delighted with the Portsmouth Scene” and “a warm admirer of the Portsmouth Scene” are two of the favorable verdicts (Later Manuscripts 231). Why were Austen’s genteel intimates so pleased by her treatment of Portsmouth and the Price family?

Portsmouth is about as gritty as it gets in Austen’s mature novels, a far cry from the refined social and material culture that many of us twenty-first century Janeites find enchanting about this period. The Prices’ small home is a dirty, noisy, almost grotesque interior we would more readily expect to find in Dickens (who was, incidentally, born in Portsmouth in 1812). And Fanny, visiting her large, lower-middle-class family after living some years with the wealthy Bertrams, finds nothing to encourage filial affection in her parents’ deplorable behavior. The other humblest abodes we encounter in Austen’s fiction—old Mrs. and Miss Bates’s cramped upstairs apartment, sickly Mrs. Smith’s small Bath rooms, the Harvilles’ tiny but ingeniously ordered house in Lyme—all invite compassion or admiration for the inhabitants. What can possibly be appealing in the “half-cleaned plates” and paternal profanity at Portsmouth? This essay will take a closer look at Fanny’s urban adventure through the admiring opinions of Austen’s acquaintance, and explicate literary and biographical clues to why these earliest readers reported finding “power,” “spirit,” and “delight” in the Portsmouth portions of Mansfield Park.

“Power”

One rainy Sunday in 1807, while writing a letter to her sister, Jane Austen entertained chatty ten-year-old Catherine Foote by letting her examine “the Treasures of my Writing-desk drawer” (8-9 February 1807).1 This visit occurred at the home she shared with her brother Francis in Southampton for the two years between leaving Bath and moving to Chawton. Southampton, a quiet spa-town on the Hampshire coast, was only nineteen miles from Portsmouth and a popular home for naval families like Frank’s (Southam 139). Little Catherine, or Kitty as she was called, was the daughter of Frank’s naval friend Captain Edward James Foote (140). Captain Foote appears to have been discerning but congenial. After dining one day with the Austens and being served “boiled leg of mutton, underdone,” as Jane Austen reported to Cassandra, the captain acknowledged a “particular dislike to underdone mutton”; he was, however, “so good-humoured and pleasant that I did not much mind his being starved” (7-8 January 1807).

By 1814, Foote was an admiral, and like his daughter an admirer of the “Treasures” of Austen’s writing desk—in this case, Mansfield Park. Austen recorded in her “Opinions” that Admiral Foote was “surprised that I had the power of drawing the Portsmouth-Scenes so well” (LM 234). Whether or not one detects an element of condescension in this response to his friend’s spinster sister, Admiral Foote was clearly struck by the realism in Austen’s depiction of a world so familiar to him. This praise was indeed “true recognition,” Brian Southam writes in Jane Austen and the Navy, as “Admiral Foote was then Second-in-Command at Portsmouth” (223).

Admiral Foote’s pleasure in Mansfield Park seems grounded as much in Austen’s accurate rendering of Portsmouth’s environs as in her subtle acknowledgement of its infamous grittiness. As Fanny’s carriage nears Portsmouth in the third volume of Mansfield Park, a material sense of the naval town’s growing significance is communicated through her “wonder at the new buildings” (MP 435) before she and William pass through the gate into the heavily fortified area now known as Old Portsmouth. The town had featured prominently in Austen family interests at least since 1786, when brother Frank entered the Royal Naval Academy there (Family Record 53),2 and it carried a “national importance” in the popular imagination as well (P 275). Coming off a fifty-year building boom that had begun in the 1760s—fueled by wars abroad and its strategic location on the coast—and now boasting the largest naval dockyards in the world, the Portsmouth area had become a key naval port and a tourist destination (Southam 221-22).

Visitors, from humble sailors’ families to royalty and foreign dignitaries, would come to marvel at the British navy’s sea power or attend patriotic events such as the king’s annual birthday celebrations (Southam 218-19). Portsmouth thus held a much more political sort of draw than other seaside towns we associate with Austen. The nearby but geographically sheltered Southampton, for example, was described in a 1799 guide to watering places as “handsomely built” and possessing an assembly room “pleasantly situated in respect to its view to the water, the New Forest, and the Isle of Wight” (Carey 76-77).

Admiral Foote might have enjoyed encountering familiar landmarks in these chapters and finding that wealthy, sophisticated Henry Crawford visited the dockyard “again and again” (MP 467). His comment that Austen had captured Portsmouth “so well,” though, points to appreciation of her technique as much as her content. Consider this deft highlighting of the port’s natural beauty when Fanny walks along the ramparts one day:

It was really March; but it was April in its mild air, brisk soft wind, and bright sun, occasionally clouded for a minute; and everything looked so beautiful under the influence of such a sky, the effects of the shadows pursuing each other on the ships at Spithead and the island beyond, with the ever-varying hues of the sea, now at high water, dancing in its glee and dashing against the ramparts with so fine a sound . . . (474)

The sinuous elegance of this Portsmouth seascape contrasts strongly with the careening cant Austen would grant Sanditon’s Sir Edward Denham to extol “The terrific Grandeur of the Ocean in a Storm, its glassy surface in a calm, . . . it’s quick vicissitudes, it’s direful Deceptions, it’s Mariners tempting it in Sunshine & overwhelmed by the sudden Tempest” (LM 471). Foote would not need such clichés and forced emotion to recall the everyday splendor—and danger—of the sea. In discussing Austen’s pioneering realism, Sir Walter Scott would praise the author’s technique of “presenting to the reader, instead of the splendid scenes of an imaginary world, a correct and striking representation of that which is daily taking place around him” (Scott 67). The Admiral must have indeed found Austen’s depiction of Portsmouth “correct and striking” to remark on her ability to capture it “so well.”

There was a seedy aspect of the town, however, to which Austen’s text unflinchingly nods in several places. Portsmouth was, like London and Manchester, among England’s fastest growing towns in the eighteenth century; the burgeoning ranks of dock- and mill-workers needed to commute daily by foot, which in turn led to the hasty erection of inferior, densely packed housing (Girouard 258-59). Although not yet designated a city, Portsmouth had a population of around 7,000 and did not lack for urban troubles (Thomas 61). Along the town’s High Street one would find “handsome Georgian houses with shops catering to the affluent,” but just off it were “filthy streets, appalling slums and abject poverty,” B. C. Thomas writes (61). As a port for sailors and marines awaiting orders or returning from sometimes years-long expeditions, there was no shortage of “Rears and Vices” to be found.3 In a 1794 diary entry, evangelical William Wilberforce wrote of Portsmouth Point: “wickedness and blaspheming abounds—shocking scene” (qtd. in Southam 218). The town’s rough reputation is captured well in period caricatures, such as Thomas Rowlandson’s 1811 “Portsmouth Point.” In this image, the proud harbor, crowded with ships and with smaller boats scuttling to and from shore, is foregrounded by the more vivid colors of exuberant port bustle and open-air carousing. It is hard to imagine modest Fanny Price stepping through such a picture, and Mrs. Price is surely not exaggerating in her lament to Henry Crawford that her daughters “‘were very much confined—Portsmouth was a sad place—they did not often get out’” (MP 466). Unlike Bath or nearby Southampton, where Austen briefly attended school and later lived with brother Frank’s family, Portsmouth was not known as a town in which genteel ladies could stroll in safety.

The robust realism underlying the Portsmouth chapters might have especially appealed to male readers like Foote and Austen’s older brothers James and Edward, who also praised this portion of the novel, Katie Halsey writes. At a time when reading fiction was often viewed as a suspicious, female activity, these male readers seem “startled” that Austen “so accurately represented the world of a down-at-heel lieutenant of Marines,” Halsey argues (132). There is indeed a gritty sort of “power” at work in the realistic details of the Portsmouth scenes—most noticeably, in Austen’s uncharacteristically full engagement here of all five senses, as Fanny’s months in Portsmouth gradually overwhelm her. For example, the author summons a physical, even spatial awareness in the reader, as Fanny and William’s carriage is “rattled into a narrow street, leading from the high street” and stops in front of the “small house” (MP 435). In a blink, Fanny is “in the narrow entrance-passage of the house, and in her mother’s arms” (436). We experience the intense closeness of the house with Fanny as she squeezes into the inadequate parlor and, later, through the narrow hallway and staircase, to her cramped upstairs bedchamber. There, Fanny seemingly suffers aftershocks as she reviews the day and feels herself “struck” by the smallness and meanness of her family’s home (448).

Portsmouth is also brought vividly alive through sound and scent. Think how keenly we feel with Fanny the thin walls and incessant activity of her family’s home—a home where the father’s voice precedes him into rooms, and is three parts nautical jargon and one part oaths; a home where little brothers cannot calmly converse with Fanny but must “run about and make a noise,” and are heard “chasing,” “tumbling,” “hallooing,” and slamming doors “till her temples ached” (438-41). Now, Mr. Price has the dubious distinction of being the only character in Austen (that I can recall) who emits an odor. We get a whiff of this disappointing paterfamilias as soon as he enters, when Fanny is “pained” by his “smell of spirits” (440). By my count, the words “smell” and “smells” only appear four times in Austen’s novels, and the two times they carry negative connotations are in the Portsmouth chapters of Mansfield Park. When Fanny later muses upon the evils of passing spring in Portsmouth, she juxtaposes the “bad air” and “bad smells” of town against the “freshness, fragrance, and verdure” of Mansfield’s grounds (500). Austen needs only a few words to recall the pungent urban air for her readers. The moated town proper now known as Old Portsmouth, where the Price family dwells, had “no watermains until 1811, no drainage, indeed, of any sort except the gutters which ran into the moat and into which everything including sewage was emptied,” Thomas notes (61). Hard by the water, fortified and densely built even for a town, Portsmouth around this time must have often given olfactory offense.

Equally arresting, among all these sensations at Portsmouth, are the visual details we get of the Prices’ depressing domestic interior, depicted with the minute flair we often associate with Dickens (consider the absurdly disorganized residence of Bleak House’s large Jellyby family, for instance). Austen does not restrict our experience of the Price home to merely seeing “stains and dirt” and “a cloud of moving dust” (508); so many of the sights here simultaneously offend the palate, such as “the tea-board never thoroughly cleaned, the cups and saucers wiped in streaks, the milk a mixture of motes floating in thin blue, and the bread and butter growing every minute more greasy than even Rebecca’s hands had first produced it” (508). Fanny, losing her bloom to bad puddings and hashes served up with “half-cleaned plates, and not half-cleaned knives and forks” (479), regards the idea of Henry Crawford dining with her family as “so horrible an evil!” not out of distaste for his company but from dislike that he should see the state of her family’s table:

To have had him join their family dinner-party and see all their deficiencies would have been dreadful! Rebecca’s cookery and Rebecca’s waiting, and Betsey’s eating at table without restraint, and pulling every thing about as she chose, were what Fanny herself was not yet enough inured to, for her often to make a tolerable meal. She was nice only from natural delicacy, but he had been brought up in a school of luxury and epicurism.4 (472)

To Fanny’s immense relief, Henry suavely declines Mr. Price’s offer of mutton—a detail that, perhaps, made Admiral Foote smile.

While the Admiral appreciated Austen’s Portsmouth, it is striking that her two naval brothers—who themselves would later become admirals5—offered no comment on it for the compilation. Austen’s dear brother Frank, whose feedback she placed first above the thirty-odd other “Opinions,” had noted the novel’s “many & great beauties” but (like many other early commentators) confessed he preferred Pride and Prejudice (LM 230). If Frank did in fact appreciate the Portsmouth scenes, we can at least infer that other aspects of Mansfield Park appealed to him more. He mentioned enjoying “many of the Dialogues” and the characters in the novel, particularly Fanny and Aunt Norris. Described as serious-minded and Evangelical at this point in his life (Southam 13), Frank would also recall the “higher Morality” of Mansfield Park when later admiring Emma (LM 235).

Charles, who was away on the Namur when Austen compiled the “Opinions,” wrote that he “did not like it near so well as P. & P.—thought it wanted Incident” (Southam 223; LM 233). Could Austen’s realism in Mansfield Park’s naval passages have seemed too familiar to these sailor brothers, too everyday to be art? Certainly many of the “Opinions” judge how “natural” or “unnatural” are the characters and plot of Mansfield Park, but—especially when we recall the immense popularity subsequently of Scott’s Waverley novels, for example, and of Gothic fiction leading into this period—we can see that interests in probability and closely observed domestic fiction were not the only literary measures readers employed at the time. Charles, for one, would later mention high praise for Waverley, also published in 1814 (Family Record 199). How might Austen have regarded Charles’s feedback? In a letter responding to her niece Anna, who must have sent along friends’ opinions for the compilation, Austen joked that her next work would cater better to an acquaintance who craved more adventure, with a sly rag on Mary Brunton’s wildly improbable 1810 novel Self-control:

Mrs Creed’s opinion is gone down on my list; but fortunately I may excuse myself from entering Mr [cut out] as my paper only relates to Mansfield Park. I will redeem my credit with him, by writing a close Imitation of “Self-control” as soon as I can;―I will improve upon it;―my Heroine shall not merely be wafted down an American river in a boat by herself, she shall cross the Atlantic in the same way, & never stop till she reaches Gravesent. (?24 November 1814)

In other words, “Incident” is overrated.

When parsing what Charles means by “Incident,” however, it is important to note his enthusiasm for Pride and Prejudice and his later warm report of having read Emma “‘three times in the Passage’” (LM 239). Charles’s enchantment with Austen’s sparkling second novel and with the spirited Emma Woodhouse might thus also point to a difficulty (like so many readers then and since) in appreciating the quiet, complex character of Fanny Price, rather than a general aversion to domestic novels on his part.

There is an additional plausible reason for Frank’s and Charles’s failure to comment on the Portsmouth scenes. Paula Byrne notes in her biography of Austen that the pair might have taken offence at their sister’s portrayal of the navy—an understandable reaction if one considers Admiral Crawford’s transgressions and the deplorable Price household.6 Intriguingly, Austen’s substantial edits to Mansfield Park’s nautical jargon for the second edition in 1816 indicate that someone with expert naval knowledge pointed out her mistakes. Frank, living nearby at Chawton Great House in 1815 and known as “correct and finicky,” would be “just the man to fasten on his sister’s nautical mistakes, however small,” Southam writes (217). We might surmise, therefore, that not all opinions of the Portsmouth chapters were recorded for posterity.

“Spirit”

Though Austen’s naval brothers were possibly unmoved by the Portsmouth scenes, Miss Alethea Bigg relished their “Spirit.” Alethea was a longtime friend with whom Jane Austen—despite the author’s single-night engagement to her younger brother, Harris Bigg-Wither—remained close. Among Austen’s final letters is one to “dear Alethea,” which angles to amuse while exchanging news about her troublesome health and, maiden aunt to maiden aunt, their respective families. Austen comically expresses “considerable astonishment & some alarm” that Alethea had left behind her best gown while traveling and cheekily notes in a postscript that her letter’s actual purpose had been to request a recipe, “but I thought it genteel not to let it appear early” (24 January 1817).

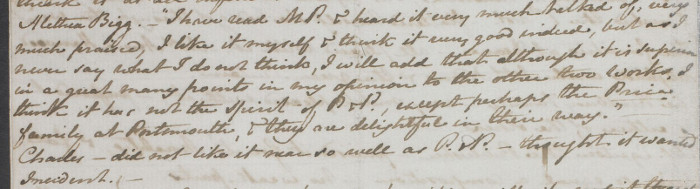

While Alethea’s opinion of Mansfield Park might remind some of the gentle rambling of Miss Bates, as with Miss Bates’s speeches, we can hear in it something really worth noting:

I have read MP. & heard it very much talked of, very much praised, I like it myself & think it very good indeed, but as I never say what I do not think, I will add that although it is superior in a great many points in my opinion to the other two Works, I think it has not the Spirit of P & P., except perhaps the Price family at Portsmouth, & they are delightful in their way. (233)

Spirit. Alethea delighted in the fully rendered life force animating the Price family, an element of the Portsmouth scenes that readers are often less attentive to today. A closer reading of the novel, however, might yield a greater appreciation for all the family—not just valiant William and virtuous Fanny. The third-person narration, filtered through Fanny’s viewpoint for most of the Portsmouth chapters, curiously insists on noticing physical handsomeness and natural ability in the less-than-genteel Prices. One Sunday, with Fanny’s family scrubbed and carefully dressed for church, we learn that “Nature had given them no inconsiderable share of beauty” (MP 473). The individual family members are likewise not without merits. Sam is “a fine tall boy of eleven years” (435) who is “clever and intelligent” (452). Susan is “a well-grown fine girl of fourteen” (436) with “an open, sensible countenance” (443), who becomes “a most attentive, profitable, thankful pupil” to Fanny (485). Tom and Charles—although “ragged and dirty”—are nonetheless “rosy-faced” fellows hale enough for prodigious door-slamming and hallooing (440). When William appears clad in his new lieutenant’s uniform, we learn that he is “moving all the taller, firmer, and more graceful for it” (444). Even the spoiled youngest child, Betsey, reminds Fanny of dead sister Mary, “a very pretty little girl” (445).

Fanny, to her intense pain, cannot view her parents with respect; nonetheless, we catch this young heroine struggling to reconcile her parents’ natural gifts with the sad use they have made of them. Fanny allows that her “dirty and gross” father “did not want abilities” (450) and can have “more than passable” manners with little effort (467), and even her slatternly mother—sister to a baronet’s wife—can muster “artless, maternal gratitude” when conversing with Henry Crawford (464). Overall, the novel ends on a markedly admiring note for the Prices. As the last chapter draws to a close, we learn that Sir Thomas can look contentedly on the trajectories of Susan, Fanny and William, as well as on “the general well-doing and success of the other members of the family, all assisting to advance each other, and doing credit to his countenance and aid” (547). The familial mismanagement and neglect at Portsmouth are disturbing, but despite this natal chaos the novel leaves us with a picture of plucky Price siblings improving their own prospects and caring for each other. It is an image that could certainly have appealed to Alethea, whose comments on Mansfield Park and Emma, Halsey argues, reveal a focal interest in “sociability and family life” shared by other early female readers of Austen (189).

In what way, however, is the Price family’s “Spirit” akin to Pride and Prejudice? This is a surprising connection, no less because so many of the “Opinions” express disappointment that the novel was not, in the words of Austen’s sister, “so brilliant as P. & P.” (LM 231). The colorful crudeness of the Prices and the embarrassing antics of Jane and Elizabeth Bennet’s family emerge as one strong point of comparison. Tom and Charles Price’s indoor tumbling, Betsey’s atrocious table manners, Lydia and Kitty Bennet’s ungoverned swooning over soldiers, Mary Bennet’s penchant for excessive piano performance, the inability of both sets of idiosyncratic parents to effectively discipline their children: there are many corollaries between the Prices and Bennets that a friend with whom Austen could joke about not seeming “genteel” might note.

After the stifling atmosphere of the Bertram country estate, the lower-middle-class port-town household could also be seen as a refreshing change of setting—particularly for the demands it places on Fanny’s activity. Fanny could never be as endearingly spirited as Elizabeth Bennet, but some readers might enjoy seeing this naturally timid heroine forced into a more active role when marooned in Portsmouth, from settling her sisters’ squabbling over the silver knife to tutoring Susan and becoming “a renter, a chuser of books!” (461). The circumstances can be heart-rending (Fanny sends her brothers on errands because she cannot stomach the food at home or walk out alone; there are no books in the Price home, so she must join a circulating library). Nonetheless, we can see why Alethea might take notice of the Price family’s vigor and natural grit, and the liveliness it injects into the novel.

“Delight”

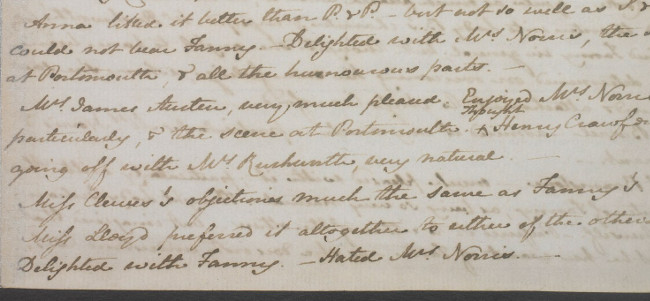

Another sentiment threaded through many opinions mentioning Portsmouth is that of amusement. Several of Austen’s earliest readers found these passages distinctly funny. Austen’s beloved niece Anna, while reporting that she “could not bear Fanny [Price],” noted her delight “with Mrs Norris, the scene at Portsmouth, & all the humourous parts” (LM 230).7

Mrs. James Austen—the former Mary Lloyd, and Anna’s “unliterary” stepmother (Honan 233)—similarly relished the comedic aspects of the novel, saying that she “Enjoyed Mrs Norris particularly, & the scene at Portsmouth” (LM 231). These early “Opinions” indicate that the same readers who could appreciate the absurdity of the mean, meddlesome (some would say monstrous) Aunt Norris might have laughed at the comic grossness of the Price family and their Portsmouth home. In his introduction to the Cambridge edition of Mansfield Park, John Wiltshire observes that the novel’s comedy has “virtually disappeared” from scholarly discussions even as critical interest in the novel has increased (lix). It is indeed difficult for many modern readers to see beyond the squalor and neglect at Portsmouth. Much of the novel’s intended humor is still accessible to us, however. Recall Fanny’s embarrassment when, out walking with Henry Crawford and Susan, they encounter a drunken Mr. Price and Fanny must introduce her father:

She could not have a doubt of the manner in which Mr. Crawford must be struck. He must be ashamed and disgusted altogether. He must soon give her up, and cease to have the smallest inclination for the match; and yet, though she had been so much wanting his affection to be cured, this was a sort of cure that would be almost as bad as the complaint; and I believe, there is scarcely a young lady in the united kingdoms, who would not rather put up with the misfortune of being sought by a clever, agreeable man, than have him driven away by the vulgarity of her nearest relations. (466)

Here, at the phrase “and I believe,” the narration archly distances itself from Fanny’s fluttered confusion to offer an observation full of humorous truth that we can still appreciate today. A newly wed (or soon-to-be wed)8 young reader such as Anna might have reveled in the absurd romantic comedy of the incident. Anna had also experienced first-hand that courtship is not always tidy, even when each party is favorably disposed to the other. Now twenty-one (and several years older than Fanny Price), Anna had at sixteen upset her family by engaging herself to a clergyman neighbor twice her age. Although her father eventually agreed to the match, Anna soon thereafter further alarmed and embarrassed the Austen family circle by deciding to end the engagement (Family Record 162).

That clergyman James Austen also pronounced himself “Delighted with the Portsmouth Scene” (LM 231) is hardly remarkable, if we remember that Jane Austen once complained of finding her “so good & so clever” eldest brother’s “Opinions on many points too much copied from his Wife’s” (8-9 February 1807).9 Though James (unlike most of the Austens) looked down on the novel form in general, a common attitude at the time, and often turned to the “higher” art of poetry for his own creative expression, he was fond of Jane and enjoyed her literary efforts especially where comedic (Honan 234-35). Where another brother, Edward (“Mr. K.”), reports that he liked Fanny and “Admired the Portsmouth Scene” (LM 230), we sometimes recall his being adopted by wealthy, childless relatives (the Knights) while a boy, just as young Fanny goes to live at Mansfield Park. And perhaps Austen’s depiction of the lively if chaotic Price household resonated humorously with James and Edward’s memories of being elder children in a large family, and with Edward’s own experiences as a father of eleven.10

There is perhaps another appeal in Austen’s Portsmouth, one to which the members of her close and clever family were especially attuned: that of its comedic theatricality. Only consider the phrases “Portsmouth Scene” and “scene at Portsmouth”; among the admiring opinions we have discussed, we can note that the five members of the Austen family circle who comment on Portsmouth use similar wording, and use the singular word “scene” (instead of “scenes,” like Admiral Foote does). As many of the Austen family were experienced amateur dramatists and enthusiastic playgoers, could they be using the word in a technical sense and referring to a specific, dramatic scene in the Portsmouth chapters? Austen may not have transcribed these opinions verbatim; possibly, “the phrasing of some of them, though not their substance, may be hers,” as R.W. Chapman suggested when explaining his rationale for including the “Opinions” in his 1954 Minor Works (vi). Still, the usage of “scene” versus “scenes” reminds us of a key literary context through which to consider readers’ “delight” in Portsmouth.

Austen had a long-standing and formative familiarity with drama, from the often-elaborate family theatricals put on at Steventon for over eight years of her childhood,11 to the “wide range of contemporary theatre” she saw with various family members as an adult (Gay 11). Animated readings and small-scale theatricals were cherished home entertainment, and the author is known to have read and acted in the frequent private performances of Edward’s large family. In one, she played the gossipmonger Mrs. Candour in Sheridan’s School for Scandal during a Twelfth Night party, taking on the part “with great spirit,” in the words of one neighbor in attendance (Byrne, Real Jane 139). This dramatic flair carried over into her reading of fiction. A niece recalls watching Aunt Jane open a volume of Frances Burney’s Evelina to “read a few pages of ‘Mr. Smith and the Branghtons,’ and I thought it was like a play” (M. Austen-Leigh 146).12 Similarly, Austen’s brother Henry would later eulogize her excellence in the art of reading aloud to her family circle: “Her own works were probably never heard to so much advantage as from her own mouth, for she partook largely in all the best gifts of the comic muse” (qtd. in M. Austen-Leigh 62).

Mansfield Park’s deep theatrical suffusion is usually discussed in relation to the staging of Lovers’ Vows at Mansfield and Henry Crawford’s beguiling reading of Shakespeare, and even the intricate framing of the Sotherton scenes. Perhaps because unlike the Austens we mainly read silently and alone, however, it is easy to overlook the dramatic elements of Fanny’s trip to Portsmouth—most especially, in her first evening at home.13 This raucous and carefully staged scene could be aptly characterized as a “set-piece,” an episode “similar in shape and length to a scene in a play” (Byrne, Theatre xii). As Fanny arrives home and is ushered into the parlor, a colorful cast of characters, starting with a “trollopy-looking maidservant” (MP 435) enters and exits; they are all trying to tell William, in their own way, that his ship the H.M.S. Thrush has already left harbor, and most pay scant attention to the increasingly dazed sister and daughter who has returned after so many years away. William packs frantically for the voyage, the younger boys chase each other about the house, Mr. Price swears, and Mrs. Price, Betsey, and the maid Rebecca argue, “all talking together, but Rebecca loudest” (441). The social order of the humble Price home is so confused that the servant’s voice usurps her mistress’s, a topsy-turvy flourish drawn by an author who like the Georgians, Byrne argues, “reveled in comedies that depicted scenes in which a person crossed the boundary from ‘low’ life to ‘high’ or vice versa” (Real Jane 147).14

The main comedic action of this opening scene at Portsmouth has a pitch-perfect finale when Mr. Campbell arrives to accompany William to the Thrush, rendered here in a single, magnificent sentence:

The next bustle brought in Mr. Campbell, the Surgeon of the Thrush, a very well behaved young man, who came to call for his friend, and for whom there was with some contrivance found a chair, and with some hasty washing of the young tea-maker’s, a cup and saucer; and after another quarter of an hour of earnest talk between the gentlemen, noise rising upon noise, and bustle upon bustle, men and boys at last all in motion together, the moment came for setting off; every thing was ready, William took leave, and all of them were gone—for the three boys, in spite of their mother’s intreaty, determined to see their brother and Mr. Campbell to the sally-port; and Mr. Price walked off at the same time to carry back his neighbour’s newspaper. (444)

Exeunt the men. If the family members who praised the Portsmouth “scene” did indeed have a passage with continuous and amusing action in mind, this could very well be it. Patricia Howell Michaelson has discussed how Austen “almost certainly wrote her novels anticipating that they would be read aloud” (195), and examines the author’s use of such features as emphasis, dialogue, and free indirect discourse to guide amateur readers-aloud in effective performance. Likewise, when some of these phrases are spoken—“and for whom there was with some contrivance found a chair, and with some hasty washing of the young tea-maker’s, a cup and saucer”—we can note how the serio-comedic subject matter and pacing that might have delighted Austen’s earliest, familial readers becomes more apparent.

Further “Opinions”

“Power.” “Spirit.” “Delight.” Do we find these particular charms in Portsmouth when we read Mansfield Park today? Focal interests shift and change, but contemporary opinions of the Portsmouth chapters—from professional critics and one cinematic response—do sometimes find a serious sort of power in this portion of the novel. In his book The Improvement of the Estate, for example, Alistair M. Duckworth explores the Price home as “a Hobbesian state of incivility” (77). For Edward Said’s post-colonial study Culture and Imperialism, Fanny Price’s Portsmouth home is a stand-in for colonies like Antigua, and Fanny is “a kind of transported commodity” for Mansfield’s consumption (88). More recently, Wiltshire has in The Hidden Jane Austen given helpful insight into Fanny’s famously “creepmouse” character through analyzing the deep psychological and physical tolls taken on Fanny by her natal home (91-121).

As for contemporary creative opinions of Mansfield Park, a controversial 1999 Miramax film directed by Patricia Rozema notably increases the structural and thematic prominence of Fanny’s home (and renders the Price family near destitute), drawing on Portsmouth for the film’s connection between slavery and Fanny’s limited options as a penniless young woman in a patriarchal society. Astonishingly, a 2007 ITV production moves in the opposite direction and eliminates Fanny’s Portsmouth trip altogether (one wonders what Charles Austen would have made of this lack of Incident). It makes a bold statement that Fanny’s story can be satisfactorily resolved without any banishment from Mansfield’s elegant, insular grounds, and that Fanny (and Jane Austen fans) can do just as well without the down-scale sights and sounds of Portsmouth.

From this filmic opinion that Mansfield Park’s Portsmouth scenes are expendable, it is striking to return to the comments of Austen’s genteel original readers, and mark again the vigorous realism, appealing liveliness, and dramatic humor that so many found in these gritty seaport scenes.

Notes

1. See also Austen-Leigh and Austen-Leigh’s Jane Austen: A Family Record (142), hereafter cited as Family Record.

2. Austen’s other sailor brother, Charles, also attended the Royal Naval Academy in Portsmouth, starting in July 1791 (Family Record 67).

3. Describing Portsmouth as “an ugly and dangerous town,” John Wiltshire expands: “Full of sailors on leave or awaiting ships, marines awaiting a posting, workmen and convicts at the dockyards, visitors and tourists, Portsmouth was notorious for its prostitutes and rowdiness” (MP 726 n4).

4. Many JASNA chapters sponsor delightful events like Box Hill picnics and Regency balls and teas—but I have yet to hear of a “Supper with the Prices” or “Mutton at Portsmouth” outing. And with good reason!

5. For a discussion of Frank and Charles Austen’s naval careers, promotions, and honors, see Southam (51-58).

6. Byrne suggests that Austen’s more evenly admiring portrait of the navy in Persuasion “was drawn with a kindlier and more respectful eye perhaps as a form of atonement” (Real Jane 249).

7. In a proto-Fanny War, Benjamin Lefroy (“Mr. B.L.”), took the opposite tack on the heroine than did his bride, but he agreed with Anna in being “a warm admirer of the Portsmouth Scene” (LM 231).

8. Of Anna’s marital status when the “Opinions” were compiled, the editors of Later Manuscripts write that the use of her given name “suggests that her opinion was written down before Anna married Ben Lefroy in November 1814 (in the ‘Opinions of Emma’ Anna is listed as ‘Mrs. B. Lefroy’).” They note that Austen’s final entry, Mrs. Creed’s opinion, was likely entered 24 November 1814 (LM 696).

9. In fact, Austen would subsequently record James and Mary Lloyd Austen’s opinions of Emma in unison, under the entry “Mr. & Mrs. J. A.” (LM 235).

10. It would be overly simplistic, however, to confuse the affectionate Austen family with the fictional, dysfunctional Prices, or even to conflate young Edward Knight with Fanny Price, as Byrne reminds us (Real Jane 27).

11. For more on the Steventon theatricals, see e.g. Gay (1-6) and Byrne (Real Jane 135-39).

12. The selection is telling: at one point in the 1778 novel, circumstances force refined young Evelina to spend time with the Branghtons, her vulgar London relations, who own a silver-smith shop, and their equally ill-bred but pretentious lodger, Mr. Smith. Austen might have read from one of several passages revealing the hilariously embarrassing behavior of the lot.

13. My terminology in analyzing the Portsmouth chapters diverges from that of Gay’s valuable study Jane Austen and the Theatre. Where Gay holds that Austen “chooses not to write them in her usual quasi-dramatic mode” (120), she is using “dramatic” in a stricter sense, to denote dialogue, as she rightly notes that the text here shifts to presenting less spoken dialogue than in the novel’s earlier scenes. I use the terms theatrical and dramatic less formally, to refer to elements of these passages—such as staging and movement, character tropes, and a performative narrative voice—that are reminiscent of stage drama.

14. Strikingly, Portsmouth is the rare place in Austen’s novels where those “below stairs” are granted a memorable (if burlesque) voice and textual prominence. We are treated earlier in the volume, however, to butler Baddeley’s hint of a smile, notably at Mrs. Norris’s expense (375). In Austen, Roger Sales writes, “deferential servants are usually talked about but not heard” (200).

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1995. ______. The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jane Austen. Gen. ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge: CUP, 2005-08. Austen-Leigh, Mary Augusta. Personal Aspects of Jane Austen. London: Murray, 1920. Austen-Leigh, William, and R. A. Austen-Leigh. Jane Austen: A Family Record. 1913. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. Boston: Hall, 1989. Byrne, Paula. Jane Austen and the Theatre. New York: Hambledon, 2002. ______. The Real Jane Austen: A Life in Small Things. New York: Harper, 2013. Carey, George Saville. The Balnea: Or, an Impartial Description of All the Popular Watering Places in England. London: Myers, 1799. Chapman, R. W. “Preface.” The Works of Jane Austen: Minor Works. Ed. R.W. Chapman. Rev. ed. Oxford: OUP, 1963. v-vi. Duckworth, Alistair M. The Improvement of the Estate: A Study of Jane Austen’s Novels. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1994. Gay, Penny. Jane Austen and the Theatre. Cambridge: CUP, 2002. Girouard, Mark. The English Town: A History of Urban Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990. Halsey, Katie. Jane Austen and Her Readers, 1786-1945. New York: Anthem, 2012. Honan, Park. Jane Austen: Her Life. New York: St. Martin’s, 1988. Michaelson, Patricia Howell. Speaking Volumes: Women, Reading, and Speech in the Age of Austen. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2002. Said, Edward W. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Knopf, 1993. Sales, Roger. “In Face of All the Servants: Spectators and Spies in Austen” Janeites: Austen’s Disciples and Devotees. Ed. Deirdre Lynch. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2000. 188-205. Scott, Sir Walter. “Walter Scott, an unsigned review of Emma, Quarterly Review.” Oct. 1815. Jane Austen: The Critical Heritage. Ed. B. C. Southam. London: Routledge, 2003. 63-72. Southam, B. C. Jane Austen and the Navy. London: National Maritime Museum, 2005. Thomas, B. C. “Portsmouth in Jane Austen’s Time.” Persuasions 12 (1990): 61-66. Wiltshire, John. The Hidden Jane Austen. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

|