|

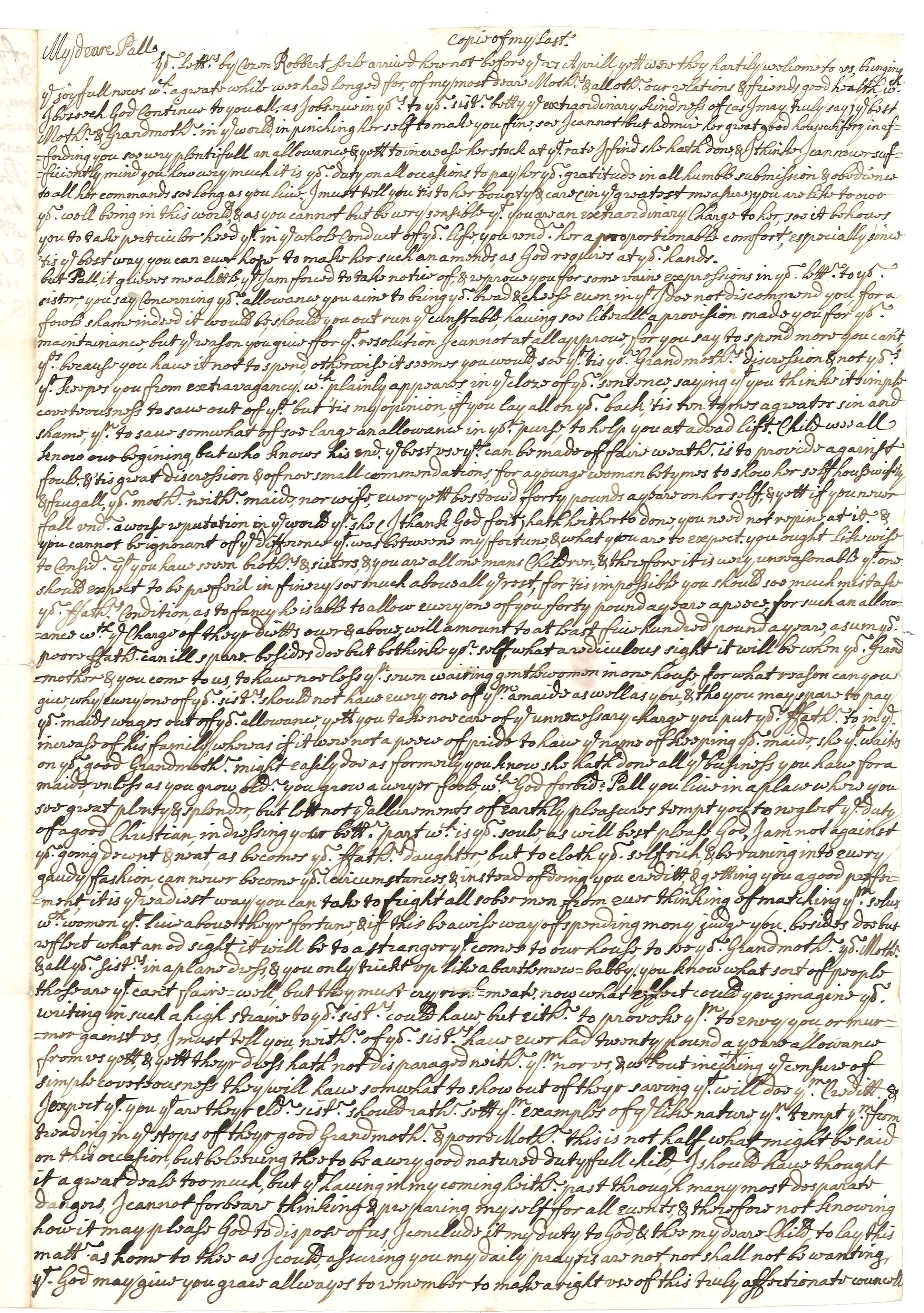

scholars have long puzzled over the printing of “A very old Letter” in the Memoir of Jane Austen compiled by her nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh (45-48). This “curious letter of advice and reproof,” as James Edward describes it (44), is transcribed in full, occupying more than three pages. The letter had been sent to Jane Austen’s great-grandmother Mary Brydges in 1686, three years prior to her marriage, in Westminster Abbey, to Theophilus Leigh of Adlestrop.1

The letter is from Mary’s own mother Eliza, Lady Chandos, sent from Turkey where the the rest of the family had been for four years, Lord Chandos being Ambassador at the Porte. Eliza is complaining strenuously about her daughter’s extravagance, and she pulls no punches. Not only, it appears, is the wayward twenty-one-year-old, left in London with wealthy relations, wasting money on clothes, but in so doing she is jeopardizing her chance of finding a sensible husband, which is the chief purpose of her staying behind. Eliza’s words tumble over one another in the energy of her rebuke (this sample is taken from the Memoir):

My deares Poll,

She draws breath.

& besides, doe but reflect what an od sight it will be to a stranger that comes to our house to see yr Grandmothr yr Mothr & all yr Sisters in a plane dress & you only trickd up like a bartlemew-babby . . .

A “Bartholomew baby” is a Londoner’s description of a woman “dressed up in a tawdry manner, like the dolls or babies sold at Bartholomew fair” (Lexicon Balatronicum). And that’s not the end of it. Mary’s provident sisters are apparently putting something aside for “a dead lift,” as Eliza calls it, and

will have some what to shew out of their saving that will doe thm creditt & I expect yt you tht are theyr elder Sister shd rather sett thm examples of ye like nature thn tempt thm from treading in ye steps of their good Grandmothr & poor Mothr.

There’s a great deal of this relentless lambasting, concluding, alarmingly,

This is not half what might be saide on this occasion but believing thee to be a very good natured dutifull child I shd have thought it a great deal too much . . .

Nor, indeed, was it Eliza’s last word on the subject.

This is delightful material to be able to reproduce in a biography of Jane Austen. The themes of propriety, husband-hunting, and good sisterly conduct are resonant; and, of course, it’s a letter. The role of letters in Jane Austen’s writing is paramount, and her own correspondence remains a fundamental source for scholars and biographers. But James Edward failed to explain why he felt justified in allocating it so much space in the Memoir. He simply wrote, “any such authentic document, two hundred years old, dealing with domestic details, must possess some interest” (44).

The lack of stated context has always invited speculation. The contemporary Spectator reviewer was hot off the mark in December 1869 (the title-page of the first edition of the Memoir is dated 1870). Acknowledging Austen-Leigh’s shortage of material, Richard Holt Hutton dares to suggest that the “very old Letter” provides evidence that Jane Austen’s good sense was inherited.

Mr. Austen-Leigh has done all in his power; he has prefixed a very attractive and expressive portrait of his aunt; a great deal of pleasant gossip about the manners and times in which she was brought up; a very sensible and amusing letter by her great-great-grandmother, written from Constantinople (where her husband was ambassador) in 1666 [he means 1686] to her daughter (Miss Austen’s great-grandmother) proving that the excellent sense and sobriety of the novelist had been handed down to her through four generations at least” (1533).

Modern scholars continue to puzzle over the significant place the letter occupies in Chapter Three of the Memoir. Professor Kathryn Sutherland, in the latest edition, accords it an extended note (220-21). She has tracked down a reference to it in correspondence between James Edward (JEAL) and his relations, copies of which are preserved at the National Portrait Gallery: “Writing to her brother as he was collecting materials for the Memoir Anna Lefroy drew his attention to ‘the origin of Poll’s letters . . . in the possession of Mrs. George Austen—it was given to her at Portsdown.” Professor Sutherland fills in the detail: “The letter must have been a cherished heirloom, handed down through the Leigh and Austen families. Portsdown Lodge, near Portsmouth, became the home of Frank Austen, and Mrs George Austen would be the wife of Frank’s son George.” But the justification for its printing in the Memoir remains unclear. Observing “the injection of mercantile wealth from Eliza’s family” into an aristocratic but far from wealthy lineage, she is forced to conclude, “JEAL’s inclusion of this letter to JA’s great-grandmother can only be explained as symptomatic of that social anxiety which surfaces in the Memoir at various points and was itself a major feature of JA’s novels” (220).

But there may be a more straightforward explanation for the space accorded to it in the Memoir. James Edward had known his aunt, and his biography in part derives from personal memory. It was after all to him, a fellow writer, in a letter of 1816, that Jane Austen made the celebrated remark about her “little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory on which I work with so fine a Brush” (16-17 December). He was eighteen when she died only seven months later, and went to her funeral, representing his father, Jane’s eldest brother, James, who was too ill to attend. I suggest that James Edward printed the text of the “very old Letter” in the Memoir because he believed that the original had belonged to Aunt Jane.

If the letter had indeed belonged to Jane Austen, it would have passed, with the rest of her effects, to her sister, Cassandra, on her untimely death in 1817. Cassandra, much later, gave anything relating to Jane to close family members before her own death in 1845. Without evidence that it had been through Cassandra’s hands, it would be difficult to argue that it had belonged to Jane. Anna Lefroy’s letter on the subject is undated: Sutherland suggests “1869?” in her printing of it in her Appendix (Memoir 184). Anna tells us that the original of the 1686 letter had been handed down through their brother Frank’s family but not how it came to be in Frank’s possession. In the same paragraph she records, “At Aunt Cassandra’s death there were several scraps marked by her . . . to be given to different relations,” but it is frustratingly unclear whether the “very old Letter” was one of these.

But there is further evidence, buried in an archive at the British Library. In 1930 Capt. Ernest Leigh Austen, Frank’s grandson, donated to the British Museum the material relating to Jane Austen that had come down to him. The five letters Jane wrote to Frank aboard HMS Leopard and HMS Elephant between 1805 and 1813, together with her poem on the birth of Frank’s son in China in 1809, formed the chief part of the gift. But the donation was of seven items—and the seventh was Eliza’s letter. James Edward, it seems, was not the only one in the family who believed that the “very old Letter” was connected with Jane; Frank’s descendants thought so too.

The inclusion of Eliza’s harangue in the gift did not go unnoticed at the time. It was briefly described by Harold Idris Bell in The British Museum Quarterly, 1930-31: “The letter, addressed to ‘My deare Pall,’ is a very racy and amusing one, consisting largely of a lecture on the sin of extravagance” (117). By the end of the thirties, however, Jane’s letters to Frank and the poem had all been published in scholarly editions. The presence of the letter from Lady Chandos became forgotten.

It is worth revisiting the archive, now BL Add MS 42180, and dusting off Eliza’s letter. James Edward had clearly not had access to the original, and neither had his half-sister, Anna Lefroy. Her reference to the recipient as “Poll,” for a start, was incorrect: Idris Bell, who had read the letter, knew that Mary’s family name was “Pall”—like Samuel Pepys’s sister—not “Poll.” Rosemary O’Day tells us that Pall’s daughter Mary, born in 1690, was nicknamed “Mall” “to distinguish her from her mother” (83).2 This is the joking of a verbally sophisticated London family, and joking much to the taste of their Austen descendants, particularly Jane. As Janine Barchas notes, “Name and word games were popular in the Austen household” (14).

Anna had only seen a copy of the Chandos letter, and a highly inaccurate one at that. The misreading of Pall’s name is typical of the careless errors that pervade the transcription given in the Memoir. The anomalous “deares,” for example, simply reflects the copyist’s unfamiliarity with seventeenth-century handwriting: Eliza of course wrote “My deare Pall.” The careful printing of abbreviations and archaisms suggests that James Edward is giving a faithful copy of the original, but this is far from being the case. There are thirteen commas missing from his version of the extracts quoted above, which are riddled with other transcription errors. Seventeenth-century forms have been misread or silently corrected: he gives the verb “clothe” where Lady Chandos wrote cloth, “running” where the original reads runing, “money” for mony, and “believing” for beleeving. Abbreviations are mistranscribed: “prefernt” for Eliza’s prefermt, “yr” for yor, “trickd” for trickt. There are also what appear to be two downright editorial changes: neither the exclamation mark that ends the first quoted section nor the ampersand that opens the second is present in the original.

The identity of the first copyist is not known. But the printed text confirms what Kathryn Sutherland tells us in the Oxford edition: “It is worth mentioning that neither JEAL nor his assistants in the Memoir were overly concerned to reproduce accurately the documents which they transcribed” (200). Copying anything to do with Jane was by then a family speciality. And then copying the copies.

The British Library archive moreover provides the missing evidence that Eliza’s letter passed through Cassandra’s hands. It is accompanied by her covering note, signed “C. E. Austen,” explaining the family connection, presumably for Frank’s benefit: “Letter from Lady Chandos, written at Constantinople (where Ld C. was Embassador) in 1686, to her eldest Daughter Mary Brydges, remaining in England with her Grandmother, Lady Bernard: Mary Brydges afterwards married Theophilus Leigh Esqre of Addlestrop in Gloucestershire & was the Grandmother of my Mother.”

Cassandra’s wording invites an aside on Austen-speak. The form “my Mother” might seem incongruous in a note written for the benefit of her younger brother, and in the same way to counter the argument that the letter could have previously belonged to her sister. We would more naturally write “our mother” in such a case. But although Jane, in her letters to her sister, regularly refers to their mother, the collocation “our mother” does not occur. The form is always “my mother”: “Do as you like; I have overcome my desire of your going to Bath with my mother and me” (25 January 1801). The same usage runs throughout the novels, leading to exchanges that sound strangely dislocated to modern ears. After Lydia Bennet’s shocking elopement, Elizabeth asks Jane, “‘And my mother—How is she? How are you all?’” “‘My mother is tolerably well, I trust,’” replies Jane, “‘though her spirits are greatly shaken’” (PP 286).

The letter, then, was in Cassandra’s hands before it passed to Frank. And the space accorded to it in James Edward’s Memoir of Jane Austen, together with its presence in Capt. Austen’s much later gift of Jane Austen material to the British Museum, suggests that that this cherished heirloom had indeed originally belonged to Jane. It is not only its subject matter that would have had particular appeal to the novelist: it is an example of her ideal letter, as described to Cassandra in 1801. “I have now attained the true art of letter-writing, which we are always told, is to express on paper exactly what one would say to the same person by word of mouth; I have been talking to you almost as fast as I could the whole of this letter” (3-5 January).

How did the “very old Letter” come to be in Austen hands?

Lady Chandos wrote regularly from Constantinople to her daughter at Wanstead House, the seat of her wealthy brother-in-law Sir Josiah Child, between May 1682 and March 1687—letters that in the most part are heavily freighted with matters godly. They are now housed at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford (DR 762/57-77), together with much else relating to the Adlestrop Leighs, preserved in a large collection of papers belonging to Stoneleigh Abbey. The Adlestrop material would have been taken to Stoneleigh by Jane’s second cousin James Henry Leigh, who inherited the Warwickshire estate in 1813. Before then he and his wife lived at the manor house in Adlestrop, now called Adlestrop Park.

The Austens, on their visits to Adlestrop, stayed at the parsonage opposite the Park as guests of the Reverend Thomas Leigh, James Henry’s uncle. Jane was fond of Thomas Leigh, describing him on his death in one of the letters to Frank on board the Elephant as “the respectable, worthy, clever, agreable Mr Tho. Leigh, who has just closed a good life at the age of 79, & must have died the possessor of one of the finest Estates in England [he had preceded James Henry as the inheritor of Stoneleigh]. . . . We are very anxious to know who will have the Living of Adlestrop.” (3-6 July 1813). When staying at Adlestrop there would have been regular visits to the Park, where Thomas Leigh’s nephew was head of the family. Park and parsonage are after all only two hundred yards apart—not half a mile, as in Mansfield Park, where an interruption to the daily intercourse signals worrying division.3 Sociable friends, like Agnes Witts, usually managed to take in both, whatever the weather. From her Diary, August 1789: “A most wonderfull hot Day quite overcoming, we were almost broil’d going in the two Post Chaises to Dine at Mr. Leighs at Adlestrop, first making a short visit at the Parsonage, sat down 11 to Dinner” (134).

When Jane was a girl, her hostess at Adlestrop would have been the Reverend Thomas Leigh’s wife Mary. A record survives of one of these visits, in the summer of 1794, when Jane was eighteen. Thomas’s wife was a Leigh both by marriage and by birth, and of a literary inclination. According to her husband, she “wrote some novels, highly moral and entertaining, on which she spent more time than agreed with her health.”4 They do not survive: perhaps Thomas destroyed them out of grief when she died in 1797.

But in 1788, when Jane was twelve, Mary had presented James Henry Leigh with an entertainingly anecdotal history of the Adlestrop Leighs. This manuscript, which is in part a guide to his inheritance, does survive: it is a handsome folio volume bound in vellum and is also now at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Mary puts names to many of the family portraits hanging on James Henry’s walls, portraits that would have been familiar to the Austens. They include paintings of Pall and her husband Theophilus Leigh: “You have a beautiful picture of this Lady by Sr Godfrey Kneller—its companion Theophilus in his long black wig and military accoutrements, I believe was painted by Jarvis” (Leigh TS folio 45). Most of the pictures that Mary describes were taken to Stoneleigh when James Henry Leigh moved there and are now on the walls of the Abbey. The large and handsomely framed painting of Lady Chandos herself, by an unknown artist, is hard to find, hidden behind a chandelier in a narrow corridor among the offices. The Leighs of Stoneleigh had after all been a separate branch since the sixteenth century and had their own eminent ancestors. But in James Henry’s time Eliza’s portrait would have been given pride of place: not only were both his parents descended from her but so also was his wife Julia, whom he married in 1786.5 Among his many possessions at Adlestrop Park were the letters Eliza sent to her daughter Pall from Constantinople, which Thomas’s literary wife describes in her 1788 history as “worthy of Madame Savigné” (Leigh TS folio 36).

Adlestrop Park under James Henry and Julia appears to have been a livelier place than the parsonage, and Agnes Witts, a great one for cards, found Thomas’s learned wife by comparison rather hard-going. “Dropp’d Mr. Witts at Chip:6 & went to to Adlestrop to make a visit to Mrs. Thos. Leigh, more agreable than usual by the adition of Mrs. Elizabeth Leigh, a very chearfull pleasant old Maid” (103). But Mary Leigh, with her novels and her old family stories, was probably more to Jane’s taste than Mrs. James Henry at the Park.

Kathryn Sutherland tells us in the Introduction to her edition of the Memoir that “genealogy seems to have been a favourite Austen pastime, and the appearance in the novels of names taken from the concealed, maternal line is evidence that Jane shared the pleasure in some degree” (xliii). A romantic story Mary tells about Pall in her manuscript must have had particular appeal.

In early youth at Wanstead, a mutual passion subsisted between Sr Josiah’s eldest son (. . .) and herself; to ask consent, he well knew would be in vain; he had therefore prevailed on his fair and tender Cousin to allow of a private Marriage; as he was leading her to the Carriage she recollected it to be Childermas day [28 December], would not proceed; before the next morning the design was discovered and negatived by the higher powers. More happy tho less splendid was her future destination. (Leigh TS fol. 44)

The name of Pall’s young lover? I withheld Mary’s parentheses: “Sr Josiah’s eldest son (afterwards the first Lord Tilney).”7

Did Jane Austen ask if she might be given the “letter of advice and reproof” on one of her visits to the Park? Or was it simply a generous gift to an interested relation? However it happened, there was a circumstance to justify the removal of this particular letter from the family archive. James Henry had two copies of it.

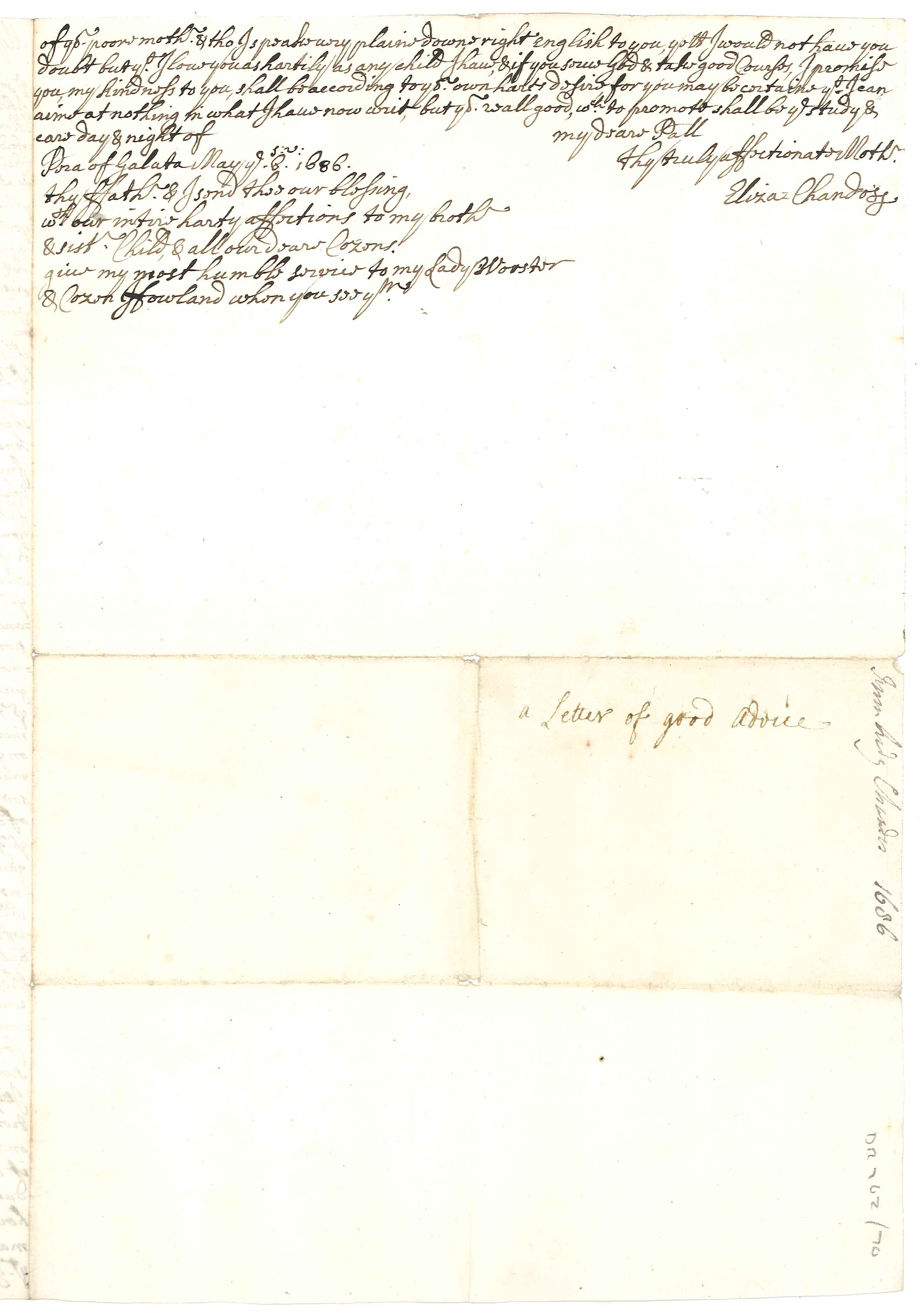

The careful transcript that Eliza herself made remains in the Stratford archive (DR 762/70), together with the other letters sent from Constantinople to Wanstead. It has probably passed under the scholarly radar because it is misdated by a day in the catalogue, which reads “5 May 1686”: the copy, like Eliza’s original, is dated “Pera of Galata May ye 6. 1686.”

This mistake is not one that the young Jane would have made. The 6th of May was one of her dates. The sprightly 1791 History of England is dedicated to Cassandra, and Jane assures her sister at the outset, “There will be very few Dates in this History” (138). But when it comes to Anne Boleyn’s doleful letter to her husband Henry VIII from the Tower, the author relents: “Tho’ I do not profess giving many dates, yet as I think it proper to give some & shall of course make choice of those which it is most necessary for the Reader to know, I think it right to inform him that her letter to the King was dated on the 6th of May” (142). Could this elaborate teasing be a reference to the Chandos letter, and another family joke?

“A very old Letter,” the copy made by Lady Chandos herself. ©Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

Alas, the copy made by Lady Chandos was no file copy.8 She appears to have sent her daughter the blasted thing twice. Captioned “Copie of my Last”—not “Copie of my Letter of xyz”—it was presumably enclosed with her next, uncharacteristically brief, note of 27 August: “I thought I should scarce have found tyme (wch I am now faine to take from my sleepe) to write to you, I am in hast, & this is only to wish you to thinke well on what I writ you last, ye advise I gave you being much for yor good I am sure” (DR 762/74).9

The lecture so eloquently preached in 1686, received at a time when Pall was recovering from her thwarted love for the wealthy future Lord Tilney, is echoed in chapter ten of Northanger Abbey. Catherine has discovered that Henry—Henry Tilney that is—is to be at the cotillion ball the following day:

What gown and what head-dress she should wear on the occasion became her chief concern. She cannot be justified in it. Dress is at all times a frivolous distinction, and excessive solicitude about it often destroys its own aim. Catherine knew all this very well; her great aunt had read her a lecture on the subject only the Christmas before; and yet she lay awake ten minutes on Wednesday night debating between her spotted and her tamboured muslin, and nothing but the shortness of the time prevented her buying a new one for the evening . . . It would be mortifying to the feelings of many ladies, could they be made to understand how little the heart of man is affected by what is costly or new in their attire. (73-74)

Whether delivered by great aunt or great-great-grandmother, the lesson is the same. A young lady’s excessive concern with dress may well destroy its own aim—or, as Eliza more powerfully puts it—“is ye readiest way you can take to fright all sober men from ever thinking of matching ymselves wth women yt live above theyr fortune.”

Eliza’s maternal insistence had the required effect. Mary Leigh’s 1788 history recounts the outcome: “Nor did Mrs. Leigh ever sigh after the great world, tho educated in all the splendor of Sr. Josiah Child’s at Wanstead House and brought up there with the future Duchess of Beaufort, Bedford, Rutland and Chandos in sisterly intimacy” (Leigh TS fol. 42). There is a later portrait at Stoneleigh of the mature Mary, looking decidedly dowdy. The husband she was to secure, Theophilus Leigh of Adlestrop, was an old-fashioned man known for his formal etiquette and traditional garb. A newfangled wife would not have been to his taste. As Mary Leigh delights in telling us, “they were models of conjugal Love” (TS fol. 36), and they were to have twelve children, one of whom was Jane Austen’s grandfather.

The story is one worthy of a novelist’s pen. But it was Jane Austen’s desire “to create, not to reproduce,” and we are told by one of James Edward’s correspondents that she had “a very great dread of what she called ‘such an invasion of social proprieties’” as to portray any real person in her writing (Memoir, Appendix 196). The preservation of social proprieties was of profound importance to her, and to her family. The letter from Lady Chandos is a highly personal one, intended solely for her daughter Mary’s eyes. Despite the passage of time, it would have remained, for the Austens, a family letter. Anna Lefroy describes how wholeheartedly she approved of her aunt Cassandra’s destruction of private letters that had passed between the two sisters (Memoir, Appendix 184), and in a similar way Caroline Austen is concerned to stress to her brother that “printing and publishing seem to me very different from talking about the past” (Memoir, Appendix 188). Such family reticence could well explain the absence of any surviving reference to the letter in Jane Austen’s correspondence, and it may also lie at the root of James Edward’s lack of explicitness when it came to its ownership history.

Notes

1. James Edward misdates the event (44), transposing the last two numbers; they were married in 1689, not 1698.

2. Pall Mall, now a street in Westminster, was opened to the public in 1661 on the site of an old pall-mall court, pall-mall being a seventeenth-century ball game not unlike croquet. I am also grateful to Professor O’Day for drawing my attention to Pall’s mother’s name. I have followed the text of the Memoir in calling her Eliza, but this may just have been her way of abridging “Elizabeth” in writing: she signs herself “Eliza: Chandos.”

3. Maria’s agitation at the non-appearance of Henry Crawford tells the story:

But they had seen no one from the Parsonage—not a creature, and had heard no tidings beyond a friendly note of congratulation and inquiry from Mrs. Grant to Lady Bertram. It was the first day for many, many weeks, in which the families had been wholly divided. Four-and-twenty hours had never passed before, since August began, without bringing them together in some way or other. It was a sad anxious day. (192)

Three chapters later, the distance between the two houses is clarified: “she had scarcely ever dined out before; and though now going only half a mile and only to three people, still it was dining out” (219).

4. From the Memorandum by the Husband of the Author of this Family History, viz: the Rev. Thomas Leigh (Leigh TS fol. 99).

5. James Henry was descended from Eliza through the male line: his grandfather was Pall’s eldest son William. His mother, Caroline Brydges, was a great-grand-daughter of Eliza through Henry Brydges, Pall’s brother. James Henry married Julia Judith Twistleton, a great-great-great grand-daughter of Eliza, descended, like him, from Pall’s eldest son, through William’s daughter Cassandra.

6. Chipping Norton.

7. As Janine Barchas astutely observes, “Wouldn’t Austen have known that the half-brother of Cassandra Willoughby, the supposed ancestor of her mother, became the Earl Tylney/Tilney in 1731?” (256).

8. There are trivial differences between the original letter and the copy made by Lady Chandos. The errors in the Memoir transcription noted here remain true for the copy.

9. The apparently intervening letter to Pall dated August 21 in the Stratford catalogue is another cataloguing error: the letter is from Eliza to her sister Emma, Lady Child.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 4th ed. Oxford: OUP, 2011. _____. The Works of Jane Austen. Ed. R. W. Chapman. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1933-69. Austen-Leigh, J. E. A Memoir of Jane Austen. 1871. A Memoir of Jane Austen and Other Family Recollections. Ed. Kathryn Sutherland. Oxford: OUP, 2008. Barchas, Janine. Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity. Baltimore: John Hopkins UP, 2012. Brydges, Elizabeth, Lady Chandos. Letters to her daughter Mary Brydges. 1682-1687. MS. Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, DR 762/57-77. Hutton, Richard H. “The Memoir of Miss Austen” The Spectator (Dec. 1869): 1533-55. Idris Bell, Harold. “Letters of Jane Austen,” signed H. I. B. British Museum Quarterly 5 (1930-31): 117-18. Leigh, Mary. History of the Leigh family of Adlestrop, Glostershire. Dedicated to the head of that Family James Henry Leigh Esqr. Written by a Relation of his family. 1788. MS. Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, DR 671/77. TS. DR 671/77a. (Folio references are to the typescript copy.) Lexicon Balatronicum. A Dictionary of Buckish Slang. London: Chappel 1811. O’Day, Rosemary. Cassandra Brydges, Duchess of Chandos, 1670-1735: Life and Letters. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007. Witts, Agnes. The Complete Diary of a Cotswold Lady. The Diaries of Agnes Witts 1747-1825. Ed. Alan Sutton. Volume 1. The Lady of Rodborough. Amberley: Amberley Publishing, 2008.

|