|

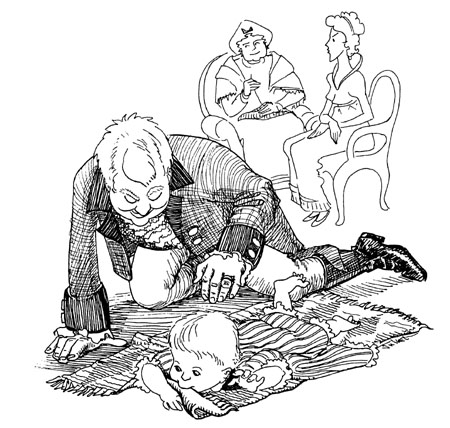

(STILL NOT THE CONCLUSION) “My dear Mr. Knightley,” said his wife, “I am resigned to the daily display of a sort of good fellowship with Mrs. Elton, as it tends to our living in peace together; but really this is going too far. Tell me we do not have to invite her sister to Hartfield, that the name of diplomacy does not demand such a thing.” “My beloved Emma,” her husband replied, “you answer your own question. In a community life, diplomacy is always required; and we can hardly show friendship to Mrs. Elton, and not to her sister. This visit, as you know, is very important to her, and in all probability, will never recur again.” Emma threw a despairing look at her friend. “Mrs. Weston, surely you do not agree with my husband? You have never given in to Mrs. Elton’s good nature – you still consider her a designing, petty, presuming, interfering little woman, do you not, with her caro sposo, and now her caro bambino, and all her airs?” Mrs. Weston’s eyes were on her little Anna, who at eight months old was attempting to creep forward on a blanket laid upon the floor. Mr. Weston was down on the floor himself, overseeing the child’s progress. Such was the disarray at Randalls since the birth of the little household tyrant.

“I do not know – oh, Mr. Weston, she must not eat the blanket, do take it away from her – it is dirty, quite dirty.” “Nonsense! who was it said a child must eat a pound of dirt in the first year.” “She shall not eat it all at once, while I look on, Mr. Weston. Here, my precious, come to mamma.” “Do not let the child eat any thing dirty, Mrs. Weston,” said Mr. Woodhouse anxiously, “and I am very glad you have picked her up. It is very chilly on the floor, I know. My own feet are resting upon the floor, and I feel the draught passing over them. I do indeed. She is much better upon your lap.” “But Mrs. Suckling,” said Emma impatiently, “what about Mrs. Suckling.” “Oh – well, Emma, Mrs. Elton is not my first favorite person, as you know, but I confess that I must incline toward Mr. Knightley's view. It would never do to offend her. I know your good nature will accept the truth of this. Is my love hungry? Perhaps we may give her some of the milk pudding that you have recommended, Mr. Woodhouse, now.” “I do not recommend most solid food for the first year of life,” he replied, “indeed, poor Isabella and poor Emma did not take any thing thicker than pudding for the first two years, if I recall aright – and then gruel, a nice thin gruel, may be taken. But I think your little Anna is not quite ready for that yet. She has only two teeth. The greatest care must be taken of her teeth, you know. Babies are delicate plants, especially young lady babies.” “That's a consideration,” cried Mr. Weston. “I am sure little Anna will like some of Mr. Woodhouse’s good gruel when she is old enough. But you were talking about the Sucklings, Emma. I hope you will invite them to Hartfield; we will have them to Randalls, will we not, my dear? In the winter, at such times as these, good company, good fires, good cheer, and plenty of it, is what is needed to help us all on.” “There, you see, Emma,” said Mr. Knightley with a smile, “you are out voted. But do not dread the event. With your interest in studying human nature, Mrs. Suckling will be sure to afford you a new subject. You know you will be talking of her and thinking of her, and so she will be a new source of pleasure, in one sense.” “Very well,” said Emma with a sigh, “I shall send out my cards, and we will have a full dinner, in state, for the Sucklings. I am sure they will be horrible in every way.”

|