Austen Chat: Episode 12

June 6, 2024

Jane Austen & Her Bookshelf: A Visit with Susan Allen Ford

"The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid."

—Henry Tilney, Northanger Abbey

As an avid reader and a novelist herself, Jane Austen of course loved to read novels. But what else did she read, and what influence did it have on her writing? What books did she place in the hands of her characters, and what do their reading habits and choices say about them? Drawing from her forthcoming book, What Jane Austen's Characters Read (and Why), Professor Emerita Susan Allen Ford joins us in this episode to answer these questions and more.

As an avid reader and a novelist herself, Jane Austen of course loved to read novels. But what else did she read, and what influence did it have on her writing? What books did she place in the hands of her characters, and what do their reading habits and choices say about them? Drawing from her forthcoming book, What Jane Austen's Characters Read (and Why), Professor Emerita Susan Allen Ford joins us in this episode to answer these questions and more.

Dr. Susan Allen Ford is Editor of JASNA’s journals Persuasions and Persuasions On-Line and is Professor of English Emerita at Delta State University. She has spoken at many AGMs and to many JASNA Regions and has published essays on Austen and her contemporaries, gothic and detective fiction, and Shakespeare. She was a plenary speaker at the 2016 AGM in Washington, D.C., and has served as a JASNA Traveling Lecturer. Her forthcoming book, What Jane Austen’s Characters Read (and Why), will be published by Bloomsbury in 2024.

Show Notes and Links

Many thanks to Susan for appearing as a guest on Austen Chat!

Further Reading Recommended in this Episode:

- Essays in JASNA's journals, Persuasions and Persuasions On-Line

- Burney, Frances. Camilla. 1796. (Link to e-text on Project Gutenberg.)

- Chapone, Hester. Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, Addressed to a Lady. 1773. (Link to e-text on Project Gutenberg.)

- Cowper, William. The Task. 1785. (Link to e-text on Project Gutenberg.)

- Fordyce, James. Sermons to Young Women. 1766. (Link to Internet Archive.)

- Goldsmith, Oliver. The Vicar of Wakefield. 1766 (link to e-text on Project Gutenberg)

Other Links Mentioned in this Episode:

- Learn more about 2024 AGM in Cleveland, Ohio.

![]()

Listen to Austen Chat here, on your favorite podcast app (Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other streaming platforms), or on our YouTube Channel.

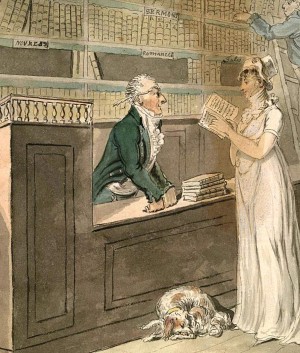

Credits: From JASNA's Austen Chat podcast. Published June 6, 2024. © Jane Austen Society of North America. All rights reserved. Illustration: The Lending Library, Isaac Cruikshank, between 1800 and 1811, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.4.867. Theme Music: Country Dance by Humans Win.

Transcript

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and readability.

[Theme music]

Breckyn Wood: Hello, Janeites, and welcome to Austen Chat, a podcast coming to you from the Jane Austen Society of North America. I'm your host, Breckyn Wood from the Georgia Region of JASNA. Today with me, I have Susan Allen Ford, who has been the editor of JASNA's journals, Persuasions and Persuasions On-Line, for almost 20 years. She is also Professor of English Emerita at Delta State University, and her book What Jane Austen's Characters Read (and Why) is being published by Bloomsbury later this year. A fellow bookworm, Susan is here to talk with us about the rich reading lives of Austen's characters and of Austen herself. Welcome to the show, Susan.

Susan Allen Ford: Thank you. I'm so happy to be here talking about Jane Austen and books.

Breckyn: Yep, me too.

Susan: It's interesting—when you said "what Jane Austen's characters read and why, I was a little startled because I always think of it as what Jane Austen's characters read [pronounced like "reed"] and why. I realized, even as I made up that title, that there was a—

Breckyn: There's no way to know.

Susan: There's no way to know. But I think of them as continually reading in the present time.

Breckyn: That's true. And, yeah, as an English professor—we're supposed to talk about characters in the present tense. Okay, well, I will know in the future what Jane Austen's characters read and why.

Susan: But it's certainly not a prescribed pronunciation for that. So, it's an interesting little tension in there.

Breckyn: Things are getting linguistically interesting already. I'm excited. I'm also an editor; I don't know if all of our listeners know that. And so, I love talking to Susan about these kinds of nitpicky, nitty-gritty, linguistic things. So, Susan, I am interested to hear your answer to our "Desert Island" segment because you've spent a lot of time in the minds of Austen's characters while researching and writing your book. So, if you were stranded on a desert island and could have only one Austen character as your pen pal, who would you choose and why?

Susan: Well, I had a hard time with this question because I don't know how I would respond on a desert island. You know, what is it that I would want, if—you know, what do I miss most on the island: talking about books or reading about people. And watching people socialize. So, I think if I were most missing books and the world of books on a desert island—and that would depend on my circumstances—I would want to write to either Fanny Price or Anne Elliot, because they both read widely and they're very thoughtful about what they read. And, you know, I think those would be interesting, but maybe earnest, letters. Well, if I wanted to have a connection to society and to kind of link to all those people that I'm missing, I think Elizabeth Bennet would be the great correspondent, because she's an entertaining social observer. But especially by the end of the novel, she has an ability to rethink her perspectives on things and to examine herself. So, I think she would be a wonderful correspondent.

Breckyn: Elizabeth Bennet is a popular choice. I will say you're the first one to mention Fanny, which is good, because I like her and I think she deserves a little more credit than she normally gets. And we're going to get into her later because Fanny is one of Austen's great readers. Okay, Susan, let's talk about books. I love your topic. Books about books are my favorite kinds of books. So, is it true that you first heard about Jane Austen from a Newbery book when you were twelve years old?

Susan: Yes, it is. For Christmas, I think in, like, 1968 or 1969—I can't remember the year—my mother gave me Irene Hunt's coming-of-age novel, Up a Road Slowly, which had won the Newbery Award for that year. And it's about this girl whose mother dies and she is sent to live with her maiden aunt, who's a schoolteacher. And the— you know, it in a lot of ways is a kind of conventional coming-of-age book. But one of the things characters—the good characters have in common is a love of reading. And during that book, Jane Austen gets mentioned a couple of times—and specifically Pride and Prejudice. Well, I really loved this novel. I've read it a bunch of times over the years and even recently. And what happened after I read it the first or second time was—it sent me to the public library, because the character Julie had mentioned Jane Austen and Pride and Prejudice. And I thought, well, I like this character. I want to see what books she likes. So, that was—I found the Jane Austen books, and here we are today.

Breckyn: That's so sweet. And one of the books that I loved as a child was—and I think many people, of course, love—is Matilda by Roald Dahl. And in that one, she goes to the public library as a child and is reading so many books. And that book made me want to read Charles Dickens because I think that was a favorite. He's a favorite author of Roald Dahl, and he mentions him in several of his different books. That's such a sweet introduction to Jane Austen. So, where did you get the idea to write your current book? Was that memory kind of in the back of your mind, and you wanted to explore Austen's characters and their reading lives?

Susan: Not immediately, but, you know, I've always kind of been interested in this. Throughout my reading, I just get kind of interested when people would mention specific titles while, you know, they were writing a book about something else; that would somehow—to me, anyway—add to the reality of that world, because here we are sharing something. So, I think in probably the mid to late nineties, I was trying to figure out what to write about for the JASNA AGM on Emma in Colorado Springs. So, that's a long time ago. And I started thinking about Emma's reading lists and how she's made up all these reading lists, apparently, and wondering what would be on those. And I was thinking about what gets mentioned. And so, for that conference, I read, among other things, Adelaide and Theodore by Madame de Genlis. And once I did that it was fascinating enough to discover all these linkages that I had no idea of—that I thought, well, this is really interesting, and if Emma has read this book, she should really know a lot and see a lot of connections that she doesn't seem to be recognizing.

And now, as a reader of Emma, I'm really thinking more about—you know, and more critically about—what Emma knows and doesn't know, as well as what the other characters are seeing. So, that's kind of where it began.

Breckyn: So, this is—this book has been a long time coming. If the first seeds were planted in the nineties, you've been ruminating on it for a long time.

Susan: Yeah, that's true. I was fortunate enough to have a fellowship at Chawton House Library in 2009, but I had to leave early, and then they were kind enough to let me come back. So, I got quite a lot done around that time—and what a wonderful place to write and research that was. But then there was a lot of family illness during the teens, and so, I had to kind of put this down for a while. But during COVID I started back up.

Breckyn: That was the time when a lot of projects were born and created.

Susan: Were rebooted anyway, in my case.

Breckyn: So, tell us a bit about the research process for the book. I imagine that creating the list of books that Austen characters read would be just a matter of going through the novels and seeing which ones she had mentioned. But once you had that list, what did you do with it? What did you want your readers to learn from the literary lives of Austen's characters?

Susan: Yeah, well, my first stage after the list was just to read the books on the list, but also read around about the books on the list, because I was also kind of interested in what people—what other readers during Austen's life—would have thought about these same books that she was reading. You know, so what was—I don't know if I can say a general opinion, but a general and or critical opinion of these books. You know, so, I would look at reviews, if they existed. I would try to find out, you know, how many editions books had gone through. Are there parodies of these books? I mean, just kind of looking around to see what the world around these particular books she's mentioning—or these texts that she's mentioning—might be. I had a couple of things in mind here. Partly, you know, as I think I've already suggested, I think this habit of reading is something that we share with Austen's characters. You know, once I read Madame de Genlis's Adelaide and Theodore, I had a link to Emma that gave me a particular insight into her character—but also into maybe the plot of the novel.

So, you know, to some degree, I see. I'm seeing more what she sees or could be seeing, but, and, you know, I'm just kind of fascinated by the issues, not just of what they're reading and why, but, you know, why these specific texts that Jane Austen is specifying. And of course, sometimes it's books that they don't read, you know, like Fordyce's sermons. They get through about three minutes. Right. And then what happens then that's interesting, but also what happens next that they don't get to hear? What implications might that have for the novel?

Breckyn: Fordyce's Sermons is probably one of the ones that comes to people's minds first, because it's also mentioned in the adaptations as well. We know that that's the one that Mr. Collins tries to lecture the young ladies on. And I think I originally—because it says sermons in the title—I used to think, oh, it's just a religious text and, so it's kind of like they're sitting in Sunday school. But isn't it actually—it's like a behavior or etiquette guide for young ladies? Is that what it is?

Susan: Yeah—behavior, education, morality, that sort of thing. You know, he also does a—I mean, he made his name as a preacher, but he also wrote a follow-up book, Addresses to Young Men. And he says in the intro to that, well, young men don't want to be—don't want to sit through sermons, or they don't want to be preached to. I mean, it's interesting because he's always trying to make a connection to them. He says, "think of me as a brother."

Breckyn: Well, and that's why Austen is such a good moral teacher, I think, because she is almost never preachy. She's so good at illustrating important moral ideas and values in a way that we can relate to without any, like, finger wagging or droning on and on like Mr. Collins. Let's talk about some of Austen's biggest readers. Can you talk about a couple of her standout readers?

Susan: Yeah, well, I mean, I think Marianne is an interesting one, but I would put Elinor with Marianne because, you know, it seems to me that a lot of the reading that goes on in Norland and then in Barton Cottage is going on out loud. You know, they're talking about the poetry that they're reading in the evening or how when Willoughby was here, they're reading Hamlet aloud. It seems like reading is a real family event, and that is, I think, typical of the period and especially of Austen's circle, where, you know, they spend a lot of time in groups reading to each other, maybe while some of them are working or some of them are doing other things. You can even see that in Austen's letters. So, yeah, those two in Sense and Sensibility—I'll add their mother and Margaret in there—are reading a lot, and what we don't hear about is the novels that they're reading in that book. I think that's an interesting absence. But I get the sense that they are novel readers, too, because—I mean, Elinor has this idea that she understands Edward's situation. You know, that she says something like, oh, yeah—or thinks it's the traditional kind of tension between parent and child, you know, and if we could just take care of the mother somehow, things will be okay. You know, she completely misunderstands that, but she reads it through her fictional—you know, a sort of fictional filter.

Go on to Fanny. Yes, Fanny is amazing. I mean, as you suggested, not just romantic poetry, though she is reading a lot, but also lots of travels—I mean, like Macartney's Embassy to China. She's reading drama. You know, she's reading a lot of different things. Crabbe's poetry is sitting there on her desk, as well as Johnson's essays. And, certainly, Anne Elliot reads a lot. And I think—I mean, we get that sense she's walking in the vicinity of Winthrop, thinking about all the zillions of poems she's read about autumn, you know, and then she gets to Lyme and talks to Benwick about Byron and Scott. And then, when she's in Bath, she's thinking about Burney's—Frances Burney's Cecilia and Henry [Matthew] Prior's Henry and Emma, or The Nut-Brown Maid. The Arabian Nights. I mean, she's just got this wide span of reading as well that we don't have complete access to but is really fascinating.

And I think maybe William Deresiewicz made this point first. Fanny and Anne both are very—they are very up-to-date readers, whereas, you know, somebody like the Crawfords—they're quoting stuff from—when they do—from way back, and you get a sense that it might be in some, you know, volume two collection of poems that they've just kind of happened across on the admiral's table, you know, or maybe Elegant Extracts or something like that. There's a lot of Elegant Extracts going on in these novels.

Breckyn: Or maybe, like, they haven't read anything since school, and so they were really just reading what was assigned, and then they haven't read anything since then?

Susan: Yeah, that's another possibility. I think you get the sense that, you know, they store their minds with kind of witty things that they can then use, you know, when the occasion arises.

Breckyn: Right.

Susan: And in Henry's case, I do not believe that he ever sat down and read Henry VIII.

Breckyn: Yeah.

Susan: I mean, my real theory is, you know, he flips through this text, which is clearly a text of the whole play, but he's probably seen in elocution texts or in Elegant Extracts, the same kinds of speeches that he's pulling out and reading—you know, because they were excerpted with little tags on, you know, for what the traits—you know, this is defining anxiety or submission or, you know, different things.

Breckyn: But that's when Fanny first starts to warm up to him—is when he— because he is a good reader, even—or he's a good "read-aloud" reader, right. He has a nice voice, and his performance is good. And maybe even if the Crawfords are all just very surface level and kind of performative in everything they do, Fanny, because she appreciates good literature so much, she also appreciates someone who can read Shakespeare well. So, that's kind of an interesting moment in the novel.

Susan: Yeah, she— I mean, it's definitely a point in his favor, but not a point finally in his favor. Right? I mean, she's able to separate in her mind the kind of—the skill of the performer and the skill of the reader from whether he seems to be a very good person. Although later on, as she starts to get to know him in Portsmouth, that's when I think she gets kind of closer to thinking about him seriously. But, I mean, I think that reading-aloud scene is a very sexual moment. I mean, you can see her attraction to him. And then as soon as she realizes it, she looks down and starts to do her needlework with as much intensity as she can. And even Austen's language in that scene really picks up that kind of erotic charge to that reading. Because it is about—yeah, it's about the body in performance and the body doing the reading as much as anything else.

Breckyn: And so, you mentioned that Fanny and Anne Elliot are very up-to-date readers. I didn't really think about this before, but do you talk about newspapers and things in your book as well, or is it mostly just books that the characters are reading?

Susan: Yeah, I don't talk about newspapers. That's a whole—that'd be a whole other thing to do. I mean, it would be a really interesting project to work on. And there's nothing much that's specific about what newspapers they're reading and why. Hazel Jones wrote a very interesting essay in Persuasions On-Line a few years ago on the Navy List.

Breckyn: Yeah, that's what I was thinking of. That and how at the end of the novel, you find out about Mrs. Rushton [Rushworth] running away with Henry Crawford from a newspaper as well.

Susan: So, yeah, I mean, newspapers definitely are part of the novel. It's just that I'm not sure how specific one could get.

Breckyn: So, we could spend an entire episode just talking about the books mentioned in Northanger Abbey, because that one, right, is a parody of Gothic novels, and so many Gothic novels are mentioned. Catherine Morland's reading gets her into trouble. She reads sensational Gothic novels that make her imagination run wild, and yet we know that Austen herself loved those kinds of books. She's not denigrating that genre, really. She's playfully poking fun. So, what do you think is going on there, Susan? There's a lot to unpack in that novel.

Susan: Yeah, there certainly is. And you're right that Austen loves the Gothic. I mean, she's reading the Gothic from one end of her life to the other. And her family's reading the Gothic. You know, we've got a letter where she talks about her father sitting in an inn reading The Midnight Bell, which is one of the novels on Isabella Thorpe's list. And, you know, even at the—around the time, maybe it's 1809 or 1810, she herself is reading a novel called Margiana; or, Widdrington Tower. You know, I mean, so, she keeps going with this.

I don't know if she's obsessed, but she certainly enjoys it. Yeah, I don't think the problem is the books themselves in Northanger Abbey, but Catherine's immaturity as a reader, you know: how she takes a genre that really is not about realism, but it's about night—is nightmare, really. I mean, it's about our anxieties. What are our social anxieties or our personal anxieties? Well, they're about fears about the family, fears about power—you know, the kind of parental tyranny, but also, you know, political or governmental tyranny—fears about the kind of role that women have in this world, that—where women are isolated and threatened sexually, but also threatened for whatever kind of money or possible power they have. You know, the ways in which women's bodies can be taken over in marriage or not in marriage. So, you know, here we've got a genre that is really exploring these issues that, yeah, Austen is interested in. But the problem is that Catherine is such an immature reader that she's just trying to make a kind of direct map of the Gothic world on the real world or fictional "real world" of Northanger Abbey or Bath. So, that's part—that's one part of the thing that Austen is suggesting, I think. But another part of it is that Catherine's not entirely wrong. So, maybe General Tilney didn't lock up his wife and feed her on coarse food for the last nine years, you know, but he's not a nice man. Obviously.

Breckyn: He starved her emotionally.

Susan: Right. He's a tyrannical parent. She can see that, although she doesn't want to see it. She does—I mean, you know, she—they talk about that toward the end more. You know, he was not, obviously not a kind husband. I mean, even Henry tries to describe him, you know, when he's dressing down Catherine for her wild imagination. But he can't say anything really positive about his father's love for his mother. He says, "I'm convinced he loved her as well as he was able to," or something like that. And then he says, "I will not pretend to say that while she lived, she might not often have had much to bear." I mean, all those one-syllable words; it’s a tortured defense. You know, he can't say anything very positive and very direct. You know, Shakespeare does that same kind of writing. You know, he'll put all these one-syllable words in a line of blank verse, and it really slows things down. And you know that there's difficulty of some sort. Well, we get—I mean, Jane Austen is a very good writer herself, and she knows how to do those things in the same kind of way that Shakespeare does.

So, I think what Austen is really suggesting is that the Gothic does have a lot to teach us. And these characters actually are not—you know, they're big readers of the Gothic; Henry says he's read hundreds—and yet he doesn't seem to recognize either what's going on. He's made a separation between his life and the life of the Gothic. And I think one of the things he's got to learn in the course of the novel is that there's not that much separation.

Breckyn: Northanger Abbey has one of my favorite scenes, and it's a rare instance where Austen just fully inserts herself into the novel, and she gives her sort of soapbox speech about how novels are one of the greatest art forms; and they have so much to teach us; and they're so valuable; and people, you know—it was fashionable at the time, or it was common, to denigrate novels, or to treat them like they were lesser, or they're silly, or they're chick lit. I'm sure you—did you talk about that scene or that sort of essay from Jane Austen in your book?

Susan: Yes, I did. I think it's great because here she is doing a defense of this genre right after, or right at the same time, she's been sort of making fun of Isabella and Catherine for being silly readers. And yet—or maybe it's right before—but anyway, I mean, she's giving us that as a kind of marker to say, you know, here's what I believe. But also, I mean, there are some interesting little jokes in that. So, she mentions in there Cecilia or Camilla or Belinda. Well, Camilla is, you know, the novel that John Thorpe has started to read and says, oh, it's nothing but a character—you know, an old man playing seesaw or something like that. And that's about in the first—I don't know—30 pages or so, let's say. I mean, it's really at the beginning, so it makes you wonder if he's ever, you know, gotten through it. Catherine hasn't read Camilla, which is interesting. I mean, she recognizes it from his description, but she hasn't read that novel. So, I mean, I don't quite know what to do with that. But it's interesting that we're not looking at her as a model of a reader.

One of the funniest parts is the mention of Belinda. Now, when I first started looking at that, Belinda is a novel that comes out in the 18 aughts. And I just thought, okay, well, that must be a way for Austen just to kind of make the reading list—or the references of this novel that she's written, you know, back between the 1790s and the early 1800s—more current for, you know, a later publication. So, I just thought, okay, well, that's an easy way of giving it a little bit of a facelift. But then I went and I looked at— you know, I started reading Belinda, and the first thing in there is this little advertisement from Edgeworth where she says, "I'm giving you this as a moral tale, not as novel, because novels have so much folly, so much error and vice." And I thought, oh, my goodness, here is Austen having this rant about the novel. And in the middle of that rant, she inserts a novelist she admires who has said, don't think of this as a novel. So, she puts Edgeworth right back in that genre, saying, we are an injured body and we have to have loyalty to this corporation, which she says something like, later in that speech. This was really interesting to me because I was always making little discoveries like this that I don't know what they add up to all the time, but they certainly give you a kind of insight into Austen's playful mind.

Breckyn: Yeah, there's the delight of finding the Easter egg, but then you're also getting layer upon layer of meaning. And that's what I was going to ask you, is like, are there any references or jokes or other things that make sense to you now that you have read a lot of these books?

Susan: Yeah, I mean, there are a lot of little jokes, you know, all the way through. The interesting thing about Austen, I think, is you don't—you can read Austen forever without knowing any of this, but once you do, it just adds these extra layers of complexity—but also extra layers of pleasure. For instance—and I don't talk about this in the book, but I do have a Persuasions essay about it sometime in the past—in Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Dashwood mentions a novel called Columella, or, the Distressed Anchoret by Richard Graves, who also wrote The Spiritual Quixote. And that came out in 1779—so, when Jane Austen was four years old. And it's a small but very significant reference in Sense and Sensibility. It has a lot to do with that novel. This novel only went through one edition. It came out in 1779. So, I mean, even by the 1790s, when Jane Austen is putting together Elinor and Marianne, or 1811, when Sense and Sensibility gets published, there can't be that many people who are readers of that novel—who remember that novel very clearly. They might get the reference, but, you know, on a fairly basic level.

But then, in Persuasion, she picks it up again without mentioning it. There's a section in Columella where one of the characters objects to the fact that these people are riding around with other people's coats of arms on their carriages, and—you know, what's happened to the country. We have all these tailors and then other things kind of taking on the names of our great families. And one of the things that is mentioned in a footnote is Wentworth, a barber of Oxford. And that picks up, you know, Sir Walter's whole thing about how our great families—their names have become so common. You know, he's thinking about Wentworth in this case. There's another point where Mr. Elliot comes by, you know, and has something over his carriage so you can't really see the arms on it, and so Mary can't recognize him. So, here she is making a joke about this novel in 1816, 1817, that probably ten people in England remember, and they might all be in her family. So, I think a lot of it is just her own kind of internal playfulness that we're seeing here. I mean, they're not gratuitous, because when you start to look at them, they actually do make sense in the fabric of the fiction. But she can't really be thinking that there are many people who would be remembering that novel very well at this stage.

Breckyn: Yeah. That brings me to what I want to talk about next, which is about Austen's own reading, because, of course, that that hugely influenced her writing. We know that she unapologetically loved novels, but she also really read widely across genres. Can you talk a bit about that, about what else she was reading?

Susan: Yeah. So for the AGM, I'm going to be talking about Austen's reading, and I just thought that was kind of an impossible goal, you know, how do you focus that? Because she's reading everything. And so I decided to look at a particular period from—you know, as they're getting ready to move to Chawton—from that point, January 1809, up to the point that Mansfield Park is published in March 1814. And I decided to just go through the letters—not look at what's going on in the novels—but just go through the letters for now and see either what she says she's reading or what she quotes, you know, just to get a sense of what—from the, you know, the fragmentary evidence we had—what was banging around in her head. And I came up—so, this is not real helpful in terms of, you know, getting me to narrow things—but I came up with at least 51 texts, and maybe twelve of them are novels. About nine are poetry. Nine are in the kind of politics/history/biography category. She's got travels and memoir, maybe four of those. Lots of drama and opera—14 different things—and then some stuff that has to do with religion or piety.

There's a print of a circulating library—I think, at Margate well, no, it's not the Margate one. Anyway, I can't remember where it is—that I'm using in the book. And you can see in the print, if you look closely, that there are labels on the shelves for these different kinds of categories. And, I mean, that really, I think, is interesting because it gives me the sense that, you know, as she's borrowing books from reading societies or circulating libraries, she's not sticking to one genre or another. She's really reading around.

Breckyn: Yeah. And that's what I love about reading the juvenilia. One of the things that I love is that you see how much she's—what a voracious little teenage reader she was. She wrote her—an entire history of England—and, I mean, it's very silly and truncated, but she's clearly read a lot of history to be able to condense it down and write her own History of England. So, it's just really fun to see that she was such a voracious reader and writer from the very beginning.

Susan: Right. And that's really fun, too, because, you know, she's writing back to those historians, like, here I am. I'm gonna tell the story now. You've had your chance.

Breckyn: Yeah. And, I mean, she's this 15-year-old girl, which, first, is a demographic that nobody takes seriously, but at the time, particularly, when women, you know, aren't really considered historians, she felt confident enough to be like, you know what? I'm gonna take on all these dead guys, and I'm gonna tell my own version. I just love the cheek of that.

Susan: Yeah.

Breckyn: So, Susan, if you had to pick just one, is there a contemporary book—contemporary with Austen—that you would recommend to Austen lovers? One that would most enhance our understanding of her life and her novels? It's probably really hard because, like you said, there are so many. But are there one or two that stand out?

Susan: Well, you know, I think a conduct book would be a slog, but an interesting slog. I mean, I think reading Fordyce teaches you a lot at Fordyce's Sermons to Young Women as well, or reading Hester Chapone's Letters on the Improvement of the Mind. She's a little friendlier to women, but, I mean, you do get a sense of how she—you know, how women are being schooled, and so, what kind of world Austen is coming out of. So, that would be one way I would answer. As you probably can tell, I don't like "choose one" questions, because I then start and—I can't choose one! But another one would be Cowper's The Task. He's writing in blank verse, but it's really accessible. And, you know, his neighbor has just said—when he hasn't known what to write about—write a poem about a sofa. So, he starts, and the sofa takes him out, you know, into a walk, and then he writes about the landscape, and he writes about the world. And, I mean, Austen's reading Cowper her whole life, and Cowper's probably in every novel. Maybe not Northanger Abbey, but I think everything else. It's just really—it's fascinating.

The other thing, since we were talking about novels and how long some of these guys are—like Richardson's Sir Charles Grandison or Burney's novels are huge and sometimes frustrating. There's a very short novel that Robert Martin reads that I would recommend: The Vicar of Wakefield, Goldsmith's novel.

Breckyn: Yes, I have that on my shelf. It is thin.

Susan: Yeah, it's thin and it's fun and it's interesting, especially if we think about it in terms of Robert Martin.

Breckyn: I like that you mentioned Cowper because I just want to get a PSA out there. This is a common problem for voracious readers—is that you read words that you have never heard pronounced. It took me a long time to realize that Cooper and Cowper were the same person because Cooper is spelled C-O-W-P-E-R. So, if there's anybody out there this whole time who has thought that those are two different poets—they're the same poet. It's just pronounced Cooper for some reason. My husband says you always know a reader because they mispronounce big words. My nine-year-old reads a lot and is always mispronouncing words.

Susan, this has been a really fun talk. I love talking about books. Thank you for coming on the show today. Where can our listeners go to learn about your book that's coming out and your other work?

Susan: Well, thank you. Jane Austen Books has it up on their website. It's going to be published on July 11.

Breckyn: Okay.

Susan: It's being published by Bloomsbury, so it's on their website as well. It's also on Amazon and I think on Barnes and Noble. One place that you can go besides those places—I mean, if you're interested in other things—is Persuasions or Persuasions On-Line. We have zillions of essays, many of them dealing with Jane Austen and the books that she is thinking about as well as other aspects of her life and works. So, there's my PSA.

Breckyn: Susan has been lovingly curating and compiling those essays for JASNA, and it's been a labor of love for her for a long time. Thanks so much, Susan. This has been really fun.

Susan: Well, thank you, Breckyn. I really enjoyed it, too.

![]()

Breckyn: Okay, friends, it's time for a stack of JASNA news. If you've ever dreamed of being immersed in a multi-day party with your best Janeite friends, put this year's Annual General Meeting on your calendar. Every year, a different city hosts a JASNA AGM, where Austen fans come together from all over the world to learn, to be entertained, and to enjoy the fellowship of like-minded readers. This year, the conference will be held in Cleveland and will be hosted by the Ohio North Coast Region. Since registration is right around the corner, we've invited the co-coordinators to give us a sneak peek at what's in store for attendees.

Jennifer Weinbrecht: Hi, I'm Jennifer Weinbrecht, co-coordinator of the 2024 AGM. Join us at the Hilton Cleveland Downtown, October 18th through 20th, where fascinating speakers will discuss topics related to our theme "Austen Annotated: Jane Austen's Literary, Political, and Cultural Origins." We want to learn what Jane saw in the world around her and how it shaped her as she created her groundbreaking fiction. In addition, there are exciting workshops and sessions Thursday before the AGM begins and activities Friday and Saturday evening, where we can learn to dance like Jane Austen, make our own book or Regency headgear, hear from men of the period about their occupations, enjoy a fashion talk and fashion show, attend a banquet and Regency Ball with live music, and much more.

Amy Patterson: I'm Amy Patterson, the other half of this year's planning team. The AGM in Cleveland also gives you the chance to experience a vibrant city bustling with world-class experiences. A few activities to choose from include a visit to the world-famous Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Cleveland Museum of Art, a Shakespeare play put on by Cleveland's resident classical troupe, a Bach concert performed by a Grammy-winning Baroque Orchestra, and several walking tours around our Gilded Age gem of a city. Day tours include a visit to Amish country or the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and a trip to President Garfield's house. On Sunday night, kick back and enjoy a moonlit dinner cruise along the scenic lakefront.

Jennifer: Visit jasna.org/cleveland2024 to find information on registration and program details.

Amy: We should also mention that you have to be a JASNA member to register for the AGM. If you're not already a member, you can join online before you register. Use the New Membership form on JASNA's website at jasna.org/join, and make sure to sign up for JASNA emails and AGM updates so you'll receive the latest information about the conference. Registration opens June 19th, and you'll want to be prepared with all of the information, so don't delay.

![]()

Breckyn: Now it's time for "In Her Own Words," a segment where listeners share a favorite Austen quote or two.

Peggy Keegan: Hi, Austen Chat. My name is Peggy Keegan, and I'm from the Maryland Region of JASNA. My quote today is from Persuasion, and it reads as follows. "My idea of good company . . . is the company of clever, well-informed people, who have a great deal of conversation; that is what I call good company."

"You are mistaken," said he gently, "that is not good company; that is the best."

In this intense digital era of ours, this quote is a timeless life-lesson about meaningful conversations, no matter one's age or circumstances. Thank you, Jane Austen.

![]()

Breckyn: Hello, Dear Listeners. I just wanted to ask you a favor. If you've enjoyed listening to Austen Chat, please give us a five-star review on Apple Podcasts and leave a comment saying what you like about the show. The more positive reviews we get, the more people will see and hear about the podcast and the more Austen fans we'll find to join our community. Though Emma Woodhouse may have disagreed, I side with Mr. Weston. "One cannot have too large a party"—or too many Janeites. Also, just a reminder to follow JASNA on Facebook and Instagram for updates about the podcast, or to send us a line at our email address, podcast@jasna.org, if you have any comments, questions or suggestions.

[Theme music]