Austen Chat: Episode 15

September 6, 2024

Cassandra Austen & Her Drawings: A Visit with Janine Barchas

Cassandra Austen, beloved sister to Jane, was a talented artist in her own right. At age 19, she illustrated Jane's satirical History of England with thirteen delightful ink-and-watercolor portraits. She continued to draw and paint throughout her life, most often copying from popular newspaper and magazine prints of the day. In this episode, Austen scholar Janine Barchas discusses her recent discovery of previously unidentified works by Cassandra and the underappreciated "art of copying," a talent Jane Austen gave her heroine Elinor Dashwood. Excitingly, there may still be pieces of Cassandra’s work out there, waiting to be discovered by you, the listener!

Cassandra Austen, beloved sister to Jane, was a talented artist in her own right. At age 19, she illustrated Jane's satirical History of England with thirteen delightful ink-and-watercolor portraits. She continued to draw and paint throughout her life, most often copying from popular newspaper and magazine prints of the day. In this episode, Austen scholar Janine Barchas discusses her recent discovery of previously unidentified works by Cassandra and the underappreciated "art of copying," a talent Jane Austen gave her heroine Elinor Dashwood. Excitingly, there may still be pieces of Cassandra’s work out there, waiting to be discovered by you, the listener!

Images of the Cassandra's drawings discussed in this episode are included in the transcript below. A video version of this episode is also available on JASNA's YouTube Channel.

Professor Janine Barchas holds the Chancellor’s Council Centennial Chair in the Book Arts at the University of Texas at Austin and for the past year has been a visiting fellow first at Clare Hall at Cambridge and then at All Souls College at Oxford. She is the author of several books on Austen, including The Lost Books of Jane Austen, and she was JASNA’s North American Scholar Lecturer at its 2013 Annual General Meeting.

Show Notes and Links

Our thanks to Janine Barchas for appearing as a guest on Austen Chat!

Further Reading

- "More about Cassandra and the Art of Copying," Janine Barchas, Persuasions On-Line, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Winter 2024)

Related Links

- Learn more about Professor Barchas

- Visit the What Jane Saw website to see digital reconstructions of two major museum exhibitions Jane Austen attended during visits to London: the Sir Joshua Reynolds retrospective in 1813 and John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery in 1796.

![]() Listen to Austen Chat here, on your favorite podcast app (Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other streaming platforms), or on our YouTube Channel.

Listen to Austen Chat here, on your favorite podcast app (Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other streaming platforms), or on our YouTube Channel.

Credits: From JASNA's Austen Chat podcast. Published September 6, 2024. © Jane Austen Society of North America. All rights reserved. Theme Music: Country Dance by Humans Win.

Transcript

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and readability.

[Theme music]

Breckyn: Hello, Janeites, and welcome to Austen Chat, a podcast brought to you by the Jane Austen Society of North America. I'm your host, Breckyn Wood from the Georgia Region of JASNA. Listeners, if you've ever poked around a garage sale or rifled through an old attic while secretly hoping you'd find a lost van Gogh, you're going to love today's episode. My guest is esteemed Austen scholar Janine Barchas, and her most recent research has taken her through dusty archives galore, uncovering artwork by Jane Austen's beloved sister, Cassandra. Janine Barchas holds the Chancellor's Council Centennial Chair in the Book Arts at the University of Texas at Austin. And for the past year, she has been a visiting fellow—first at Clare Hall at Cambridge, and then at All Souls College at Oxford. She is the author of several books on Austen, including the award-winning The Lost Books of Jane Austen. And in 2013, she was JASNA's North American scholar. She has recently been exploring Cassandra's practice of copying popular prints of the day and its connection to Austen's work and to the larger Austen family. Excitingly, there may still be unidentified pieces of Cassandra's work out there waiting to be discovered.

Breckyn: Welcome to the show, Janine.

Janine: Thank you, Breckyn. It's really nice to be here.

Breckyn: To start off, we're going to play an Austen version of "Would You Rather." To go along with today's art theme, would you rather take drawing lessons from Elinor Dashwood or harp lessons from Mary Crawford?

Janine: Am I to answer this?

Breckyn: Yes, that's you.

Janine: I was hoping you would get input from all sorts of other people already! But of course—okay, so I would say that it depended on whether you really wanted to learn drawing or really wanted to learn the harp. And I think musical instruments aside, which is probably very difficult, if I really wanted to learn how to draw, I would love to have Elinor teach me. But if the point was to meet an Austen character, I think I would rather meet the spicy Mary Crawford and assume that the conversation, while a bad harp lesson from which I would learn practically nothing, would nominally take place.

Breckyn: I was wondering if you had already had some artistic background, based on your interest in this research. Have you ever taken any art classes or anything?

Janine: Sure. I mean, everybody's taken some art classes, and I've done a little modest sketching of the sort that I would never own up to or share. I'm a very visual person, and many of my projects have taken me into art history, and it's sort of the area I love, although that's not necessarily, as you know, what led me to Cassandra. It wasn't because I'm an art lover that I ended up—although I suppose one reaches for what one knows.

Breckyn: Right. What did make you first look into the artistic habits of Cassandra Austen?

Janine: I'm glad you asked. So, I've been researching—as you said, I was in England for a year, and I've been researching the stuff you could rent in Jane Austen's time, especially luxury items. They were often rented by women. So, everything from pianos to pineapples, jewelry to silverware, were luxury items—things that suggested social standing—and they could be rented as well as purchased. I ended up studying or zooming in in a certain chapter in a certain point of the research on a shop in London in the 1790s that rented prints. And one of the ad copies for the shop was "Lent to Copy." And I thought, Lent to Copy? Why would you hire a print in order to copy it at home? And I thought, of course, this was the age before the photograph, and I could see why that skill in duplication is something you would want to rehearse. But I thought, okay, well, who do I know that could be an example of that for my readers? And so that's when I reached for what I know, which is the Austen family. And so I thought, okay, I remember Cassandra doing something that connected to prints. And then when you scratch one area—I'm Dutch, and so when you clean something, you got to do the whole room—and so suddenly I was looking at—I thought, okay, there's so few works that still survive by her, I'll look at all of them and see whether they are examples of copying. And almost all of them turned out to be, other than the things that were family portraits, like the scratch of Jane that's in the National Portrait Gallery and that's now made its way via the bad Victorian engraving onto the 10-pound note. Everything that she did seems to be—not everything, but a lot of things—seem to be copies of popular prints that were loaned, presumably.

So that particular shop aside, which—that's part of my research about the book—I suddenly ended up in this rabbit hole that was Cassandra's copyist work. And it turned out that all her life long, she copied from popular prints, and that her family knew this, and her family prized that skill. And one can well imagine in the age before the photograph or the Xerox machine, to have a skill that really copies something—she was a veritable human Xerox machine. I mean, she's good at copying things. And so, yeah, that was a skill that she clearly shared with nephews and nieces and friends and family members, and they prized those things and they saved them. And so they're popping up in that context.

Breckyn: And luckily, didn't burn them like Cassandra did with a bunch of Jane Austen's letters.

Janine: No, but why would you burn—yeah, this is about your aunt made you a picture, and so you save it. Or your sister made you a picture, and you save it.

Breckyn: And so our definition of what "counts" as art has changed a lot since Austen's time, partially thanks to the Romantics you've mentioned in your article. But can you talk a bit about what Cassandra was doing, and then why opinions soon changed and started looking down on this art?

Janine: Sure. Yeah. And it makes sense when you think about it. Cassandra was copying something that she would come across in a book, or I'll show sometimes it's a magazine, sometimes it's a book, sometimes it's a loose print that also circulated. And she then copied it for a friend, for a relative—the family are the ones who've saved it. And so this was a skill about holding a mirror up to this object and being able to share it before Instagram and before Facebook. To share images is an impulse that we still very much have, we just use different technologies to do it. And this was about a lady artist having the skill to—or any artist, really—to have the skill to copy things and to share those. And then—and this imitative skill was very much prized. But then Romanticism rears its head and prizes original genius instead of any kind of imitative skill and begins to demote that particular skill over invention. And so, Romanticism hails invention as true art, as opposed to anything imitative, which is mere copying. And so, suddenly, copying begins to be kind of mere skill as opposed to art. And that totally wasn't true.

Janine: I mean, in the age in which Austen and Cassandra grew up, engravers were paid significantly more than painters. So in Shakespeare's—in the Shakespeare Gallery . . . Boydell Shakespeare Gallery, that I recreated in What Jane Saw, the website—Boydell paid the engravers of the pictures more than he did the original artists, unless they were members of the Royal Academy. And so taking something, whether large or small, reducing it in size, enlarging it in size, copying it in whatever size—doing that accurately was a revered skill that, in terms of copper plate, took a lot of time and was paid accordingly. And so, I think in this tradition of revering plates as views of—and in Emma, they're looking at views of different cities in Europe during the strawberry-picking scene—those who are inside with Mr. Woodhouse are looking at pictures—those kinds of prints are revered. But then different kinds of printing techniques evolve in the early 19th century, and photography takes hold, and Romanticism has made us prize original genius, so that when it comes to the history of Cassandra's art and its reception, it just has fallen by the wayside as, oh, it wasn't really—the things that survive have been looked at under the guise of "oh, it must be an original work." And then when things haven't turned out to be original works, they've been moved to the side as, "oh, whoops, I guess she wasn't an artist." And that isn't the case. This was a real—

Breckyn: It's silly.

Janine: Yeah, totally silly.

Breckyn: Yeah. Well, as someone with very little artistic talent, I find Cassandra's copies incredibly impressive, and we're going to look at them together in a bit. But how old was she when she started, and what was her artistic education like?

Janine: So, the earliest one that I can point to—and notice that I didn't say survive because the family may have others—but the earliest one that I point to is from the History of England—so, the text that Jane Austen wrote as a satire of history and history telling that is illustrated by her sister. In that History of England, Cassandra provides 13 images, and she is then 19 when she does that. And the last one that I can point to—she is 61. So, yeah, from 19 to her early '60s—

Breckyn: A lifelong pursuit.

Janine: It's a lifelong pursuit. And so, of that, only less than a dozen am I able to point to and say, "oh, definitively, here's the image she did, and here's the print she copied it from." But there must be many more images. And when we go to specific ones, I'll be able to say the family didn't know that this was a copy of a print, and they saved it because it was a picture done by Cassandra, or a watercolor by Cassandra, or a sketch by Cassandra. And so, these things might now be looked at in a slightly different context to see, well, what else did she copy from? And why did she choose that out of that book or out of that particular magazine?

Breckyn: Yeah. Well, like I mentioned at the beginning, there's some real treasure hunt vibes to your research, and it's very exciting. And we'll talk some more about it in a bit. But let's talk about the images themselves. For those listening to the audio version of this episode, the images are available on the podcast episode page. And if you want to come join us on the video version, it's posted on JASNA's YouTube channel, and the link is in the show notes. But, Janine, you have quite a few of Cassandra's works to tell us about, but let's go through just a few of them, and you can tell us about them.

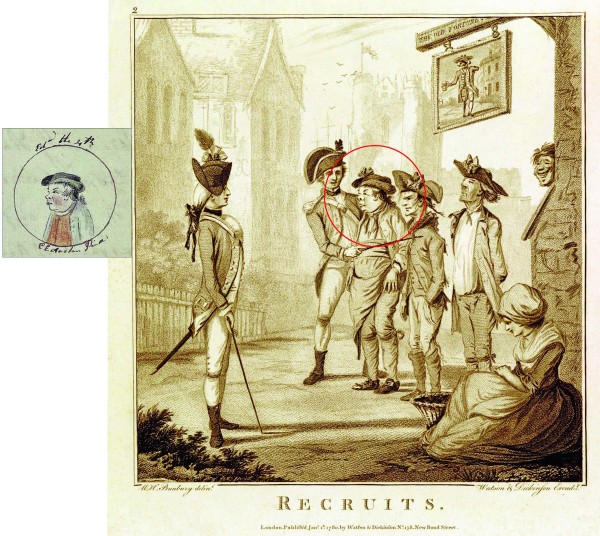

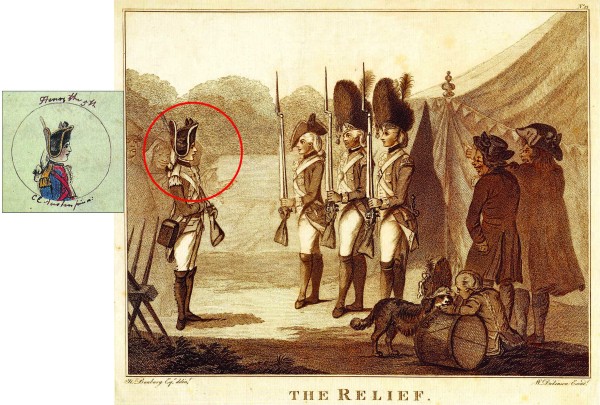

Janine: Yes, let me share. Voila. Yes? Okay. So, this is the first one that I can point to [Image 1]. And when I say first one, I mean chronologically. This is from the 1790s. And if I'm not mistaken, the History of England is 1795. No, 92. So this is 1792. So, this is when Cassandra is 19 years old. And here you can see on the left, the image as it appears as a little roundel in the fair copy manuscript that we have that's in the British Library. And you can see on the right, the print from—called The Recruits by Henry Bunbury, and he was known as a kind of second Hogarth. And you can see that it's a perfect match. Notice I'm at image two. Let's see whether we can make it image one. Here's the other one. [Image 2]. Also by Henry Bunbury. This print—it's sort of a set. They circulate both together and separately, and they're clearly both about army things. And here is The Relief, and here is The Recruits, and here is Henry the Fifth, as he appears in a roundel by Cassandra. The perfect circle was probably created by taking a coin and drawing a pencil around it. And when you overlay them, which you can neatly do—not in this slideshow, but I do in the article, and for research purposes—you can see that she did draw it freehand This is not—she didn't put the print underneath the manuscript and trace it. So, it takes significant amount of skill, a 19-year-old, and—

| Image 1 |

(Click here to see a larger version.)Left, Cassandra’s “Edward the 4th” from The History of England (1792); Courtesy British Library, Add. 59874. Right, Henry W. Bunbury, Recruits (1780); British Museum J,6.47; ©The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. |

| Image 2 |

(Click here to see a larger version.)Left, Cassandra’s “Henry the 5th” from The History of England (1792); Courtesy British Library, Add. 59874. Right, Henry W. Bunbury, The Relief (1781); British Museum J,6.48; ©The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. |

Breckyn: Well, you mentioned another way you know that is when it's significantly enlarged or zoomed in, right? You know—or zoom in or zoom out. There's no way you can trace that. You just have to be able to freehand that.

Janine: That's correct. And many of her images look like facsimiles, like she could have put them against a window and traced them. They're that good. And these are that good. But when you actually—as I did—go to The Recruits, you realize, in terms of measurements, that the print is actually much larger—it's quite a large print. The figure in the print is larger than the figure in her circle in the manuscript. And so, yeah, she had to shrink this one, so she had to have drawn it freehand.

Breckyn: And weren't you also saying that maybe the images that she drew from add to the satiric nature of Jane Austen's text? Can you talk to that a bit?

Janine: I think so. Yeah. Academic reception of the History of England includes some speculation that maybe these two characters and the other eleven versions of kings and queens might be based on family members. But here you have prints that are clearly not based on family members, and there's no customization here at all. But yeah, it is—these are kings and queens, and these are just ordinary blokes, lifted out of prints and placed in that authoritative position. And, of course, that is in keeping with the satirical tone of Jane's text. And so, these two sisters are—each in their own artistic realm—performing the same satirical function and the same joke, if you will, making the ordinary extraordinary and back again and mocking a certain formalistic style of history.

Breckyn: And I love the idea of them closeted together, giggling, sketching, coming up with ideas—this little collaborative effort. It makes me think of C. S. Lewis and his brother, when they were young, wrote comic books and stories together that later maybe influenced Narnia, because they were about animals and talking animals.

Janine: I didn't know that.

Breckyn: Yeah. In Northern Ireland, I believe, or I'm not sure if he's from regular Ireland or Northern Ireland. But as children, they were this brother duo, who would write stories and illustrate them together. And so that's—

Janine: How wonderful.

Breckyn: Yeah. Yeah. It made me think of that.

Janine: Absolutely. And the Brontës, of course. Those siblings—

Breckyn: Oh, the tiny books that they made? The super small ones? That's really fun.

Janine: There's some here at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, and—

Breckyn: Oh, awesome.

Janine: Yeah. But that idea of brothers and sisters and siblings collaborating must have been the case. And maybe the brothers were even in on—I mean, this is—these are the kinds of prints that young men have.

Breckyn: Yeah, you said that they're masculine images.

Janine: Yeah. And so, this feels like a sibling project that involves more than even just the two of them.

Breckyn: Yeah. That's a lot of fun. Okay. Those are from the History of England, and then did you want to move on chronologically, or . . . ?

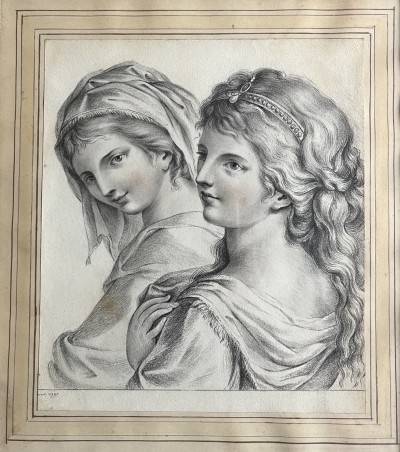

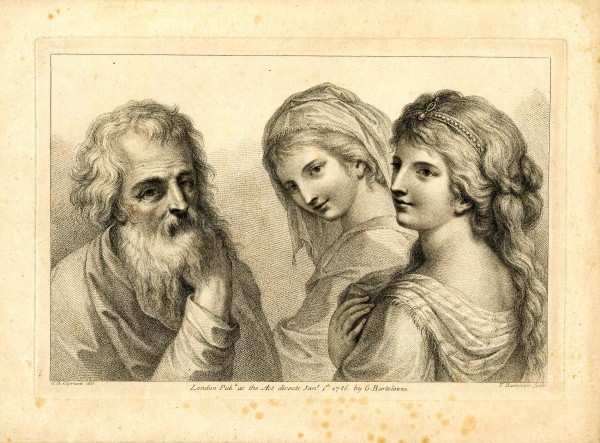

Janine: Yeah, chronologically, we have here—now we're in 1795 or thereabouts, and we have two images that actually arrived last in my hunt, if you will. And this one [Image 3] has just moved from private hands to Jane Austen's House Museum in Chawton. And this was copied from this print. [Image 4] And the owner—the family who had preserved it, who were descendants of Charles Austen—did not know that this was a copy of a print. Instead, in the family, this image circulated as the sisters, Cassandra and Jane. If you then take this print by Cipriani from 1786, from which it is a direct copy—but only on that one side—you can see that there's no customization either. This is not Cassandra and Jane. These are two Italian women, imagined or otherwise, in this particular print. And when you go back to Cassandra's sketch, her copy, you can see in the bottom left-hand corner that it just says "une, 1795," presumably "June," and, presumably, there was something else in front of it, because, presumably, this gentleman was there as well and has probably been cropped out.

| Image 3 |

Cassandra’s pencil sketch, courtesy of Priscilla Shepley. |

| Image 4 |

From Cipriani’s Rudiments of Drawing (1786); British Museum 1871,1111.782. ©The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. |

Breckyn: It's like a bad breakup. Get him out of here.

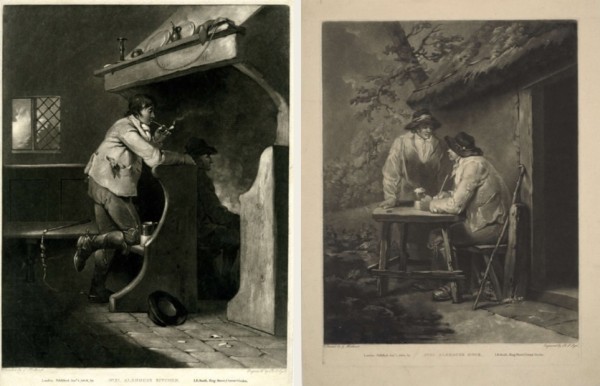

Janine: That's right. I don't know why or when that occurred, or even if Cassandra did it herself, or whether that was just part of the tradition in the family to focus on the two sisters and that's why that was kept. But here's another two prints [Image 5], and these are prints of the work of George Morland, a painter who Austen clearly knew about as well. Not only did she have a heroine named Morland in Northanger Abbey right around the time that this was made—that Cassandra made her copies, apparently—but in Northanger Abbey, a George Morland makes a cameo appearance as well by the cottage door, which is these kinds of pictures that he was famous for, although this was called the Alehouse Kitchen and the Alehouse Door, I think. But I can't show you Cassandra's images because—although they were sold at Sotheby's in 1972, I believe—they are now lost. And so, this is where the hunt begins. Sort of like, go out there! Many of these images by Cassandra were mistaken for colorized prints. And so, it's signed "CEA," both her works, and they were sold at Sotheby's as copies by Cassandra Austen of these two prints. But they no longer survive; the family can't locate them anymore.

| Image 5 |

(Click here to see a larger version.)Left, print after George Morland, Alehouse Kitchen (1801); British Museum 1873,0510.2628. Right, print after George Morland, Alehouse Door (1801); British Museum 1859,0709.776. Both images ©The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license. |

Breckyn: So, that's how good they are—is that people thought they were prints, but they are originals. So, do you have advice about—I would think that you could look at it and you could tell this has artistic material, like paint or pencil on it, but maybe you can't. You study these things so closely, to the point where you're seeing little pin marks in the corners and things like that, so you know that maybe she pinned the original on top of it or something like that, or underneath it. If people were trying to look, what should they look for? I guess a signature?

Janine: I think you should look for—this one's unsigned, but you should look for this kind of signature on the bottom left, bottom right, anywhere, that's C-E-A or C-E Austen. The ones that are signed, and most of them are, are signed in that way, and they often have a date. And they look like this one, which was also in private hands, and now is with the cottage museum in Chawton [Image 6]. This one is It's been sunned, if you will. It's been exposed to sunlight, and so the colors have faded. But it was clearly colored. And so I found this image—actually, a curator found it for me in an Italian museum— that is black and white, but it also might have circulated in color. And so maybe she's reproducing colors on another image that I haven't found yet that might have circulated. So, there are all sorts of ways in which these images could have reached her, and then she decided to copy them in her own way. But look how accurate that is. I mean, you're not looking for somebody who's riffing on an image and making it their own. No, this is about somebody who's artistic powers and interests are about copying.

| Image 6 |

(Click here to see a larger version.)Left, Cassandra’s pencil sketch and watercolor, courtesy of Priscilla Shepley. Right, Conjugal Love, engraved by Bartolozzi after Cipriani (1786); Instituto Centrale per la Grafica, Rome S-FC70120. |

Breckyn: And usually as gifts, right? This one that you have up on the screen now of the mother and baby—wasn't it a gift for her brother and sister-in-law who were going to have a baby, you said?

Janine: Yeah, it was made in 1808. It's the date, or 1806. The date is 1806, and that is the year that they moved towards—that Mary Austen, Frank's wife, first wife—was pregnant with her child, and the Austen women were there in Southampton with Mary when she had her baby. And so, yeah, maybe this is about celebrating that. But there were a lot of Austen women who had a lot of babies. I can't know for sure, but I was just going off of where the women were . . . where Cassandra was in the year 1806 when this was made.

Breckyn: So, that is really fascinating. Seeing the images side by side really underscores Cassandra's skill for me. Like I said, I have very little artistic skill of my own, so if anyone can copy that accurately. I think it's really incredible. Where in Austen's fiction or letters do we see mentions of the kind of art copying that Cassandra did?

Janine: Good question. In Sense and Sensibility, Colonel Brandon visits and has a discussion with Elinor when they're in London, and he's the one who spies her moving towards a window. Can I read you the quote, which I haven't committed to memory? "On Elinor's moving to the window to take more expeditiously the dimensions of a print which she was going to copy for her friend, he (Colonel Brandon) followed her to it with a look of particular meaning." So, this is just a throw-away in Sense and Sensibility. But it's the kind of knowing throw-away that Austen has so many of, where you don't notice it first.

Breckyn: It adds to the realism. Yeah. I don't think I ever noticed that, and now I'm always going to notice it because you pointed it out.

Janine: And for me, too. I didn't—until I was hunting for it I hadn't noticed it either.

Breckyn: Well, and you said she's moving towards the window because she's going to hang it up in the window to get the light through, do you think? Or just to get light on it so she can see it better?

Janine: To get light on it, to see it better. She's taking the dimensions of a print to copy it. So maybe Cassandra used a grid system where she had the same dimensions on a piece of paper as the dimensions of the print. And most of her copies are, in fact, almost like little facsimiles because they are the same size. And maybe she put a grid pattern underneath it. Maybe she did hold it up against a window, tape it even or fasten it in some way, to create a light box, if you will—to be able to trace part of the print or key elements of the print. I don't know how she did it, but all of those things are possible. And manuals that teach, especially young people, how to copy things—which was a thing at the time—suggest all manner of ways that you could copy a print. You could put crayon on the back and then basically trace with some slightly blunt, not too sharp instrument through. And then press those outlines, and then move it to the side, and then go and fill it in. You could use a light box, a window. You could use tracing paper, but it wasn't invented yet until after Austen's own death. So, there are a myriad of ways in which you could copy things, but you needed skill. And copying was the first phase often of training an artist. And so, this is where young people began. And the Brontës also copied things. And Cassandra clearly copied a lot of things, but she continued to do it her whole life long.

Breckyn: And Austen's juvenilia is copying many, many different writing styles, and novels, and all the different things that she—like you said, that's an artist in training. That's where you start. And clearly, Cassandra had to have a really sharp eye to execute these images that you've shown us. So Jane Austen also mentions prints in her letters, or does she mention Cassandra's art at all?

Janine: She does. So when they move from Steventon and they're planning to move from Steventon to Bath, reluctantly on Jane's part, Jane writes a letter to Cassandra. Cassandra was probably attending one of their sisters-in-law in their lying-ins. But Cassandra is away. She writes a letter to Cassandra saying, your prints are obviously going to come with us, but did you know that our brother apparently gave us the botanical prints in such and such a room. Did you know that that was . . . —so, she discusses the fact that the things that are on the walls at Steventon are going to come with them and mentions Cassandra's art. So, I assume that from the very beginning, from Steventon forward, Cassandra's pictures—many of them were copies of prints, but still prized as pictures by her. They weren't masquerading as original work. They were images that were copied, and often she even signs them with the name of the original artist, just as you would if you were engraving them and transferring them from one medium to another. And those things decorated their living spaces.

Breckyn: They were valuable decorations and pieces of visual art in their homes, right? Yeah.

Janine: And made by her, they were even more valuable and, therefore, passed on to other family members in the way that I think we all do when we have an artistic member of the family, and we frame their things, and we keep them around, because—and this is true of Elinor's screens in Sense and Sensibility, where you see that. And it's, of course, true of Jane Austen's own written work that was read aloud in the family, and that—there was a lot of cheering each other on.

Breckyn: It's meant to be shared and enjoyed and was part of the Austen family. So, what's been your most exciting discovery so far in this line of research?

Janine: Well, I I was in England for a year, so there were lots of exciting things, to be truthful. But I guess the stuff that doesn't happen in Texas is when you give a talk about Cassandra's art, in this case, and you say, wink, wink, nudge, nudge at the end, thank you for listening. And as you see, Cassandra was doing this from 19 to in her 60s, so there must be so many more examples than the seven I've just shown you. Keep an eye out. Thank you. Then there's applause and everybody goes their different ways. But then two people came up to me at the end of my talk. This was in Exeter, the Jane Austen Society there. They said, "Excuse me, thank you for your talk. It was very nice. We think we might have two of what you're looking for."

Breckyn: Did your heart just go pitter-patter?

Janine: Oh, my God. I was like, "What?" And they explained that they were descendants of Charles Austen, Jane Austen's brother, and that over the couch at home they had a couple of pictures that they had never considered copies of anything. But after my talk, they thought, maybe these two are also copies. And you and I didn't get to those two pictures in the slideshow, but we got to the other two—the mother and child and the two sisters, let's call them, by Cipriani. Those images then came about when I wrote up these two new images, and I thought, oh, gosh, this is not what I meant to be spending my time doing. I was meant to be researching stuff you could rent, and there's lots of cool research doing that.

But now I know of two works by Cassandra, because I did the research, and they came in to visit me at All Souls, and we had a lot of correspondence and photographs exchanged. And I was able to source those two pictures by Cassandra and where they had come from. And so I wrote it up, and I sent it to them. And I said again, wink, wink, nudge, nudge, just be sure to share with the rest of your family. And the next day—

Breckyn: Such bounty!

Janine: I had an email from someone who said, “I think I have two more of what you're looking for.”

Breckyn: Those Brits don't even know what they've got in their attics.

Janine: But the family prizes these things. But I guess these are like first editions that some people have. These are almost conversation stoppers, right? Like, ooh, I have a picture by my great, great, great aunt, Cassandra. And you say, ooh, how cool. Because it is. But then—but if someone says, "oh, Cassandra, her whole life copied things," then you say, "well, I have a picture by my great, great, great aunt Cassandra, but do you think it's a copy? Where might it be sourced from?" And suddenly you're hunting, and these family members hunted right along. It was really fun, I think, for all of us. And so, hopefully, the articles will animate the conversation, and maybe bring more of them to light.

Breckyn: Might be just the beginning.

Janine: Because there must be more. There must be more.

Breckyn: Yeah. And what I really like about this, just to reiterate, is that there's two prongs to this treasure hunt, and there's one that American listeners probably can't help that much with, but there's one that they can. So, the one—I think we need British listeners to just look through their attics and ask their great grandmas about—

Janine: Absolutely. And look twice.

Breckyn: Look in the chest and look on those prints that you overlooked on the wall.

Janine: And move things. Look like a girl, not like a guy. Move things around.

Breckyn: Look under things. Like I'm always telling my kids, under things.

Janine: Behind things. That's right.

Breckyn: So probably—if you live in the US, you're probably not going to find those things. But the other prong of this treasure hunt, like you said, is finding the print sources of what Cassandra copied. So you found the sources of two of the faces, or the portraits, from Jane Austen's History of England, but we don't have sources—

Janine: Someone else did that before me in 2008. We just didn't really pay attention because there was only that example. But now that we have many more, we should keep—

Breckyn: Look

Janine: Again, yeah. But you're right. We now have two examples of the 13 of those little portraits that are definitively—because I think that those examples are definitive—of her copying prints.

Breckyn: So if you want to look side by side, you've got your copy of the History of England or look up the images online, and then looking through old prints from the late 1700s, early 1800s—I guess it would have to be late 1700s, right? If you could find the original image, wouldn't that be fun? I want to go on that—

Janine: Yeah, any image before 1792 would have been fair game. The examples that I have shown you—although they were found by somebody else—those two examples suggest that near-contemporary prints were being sourced, but it could have been pictures in books as well. But the joke there, if there is a joke, is like, these are ordinary blokes and now they're being elevated to—

Breckyn: Royalty

Janine: Yeah, to the status of kings and queens. So that's where I would look. But that means that you're looking at the whole haystack of popular prints for those needles. And since Cassandra copied out of books, and out of magazines, and from loose prints, it could be anything. And the hunt is on.

Breckyn: We're going to crowdsource this. Austen Chat is going to find one of them. I'm so excited.

Janine: That would be that would be terrific because it makes sense that they are there to be found. The problem is when you—Google Image is getting better. The reverse image search gets better and better and better each time. But Jane Austen's images are so prominent that any version will get you the same thing again. So that was not the way to find any of these.

Breckyn: Got to do it the old-fashioned way.

Janine: The old-fashioned way, yeah. Get through, even if you're doing it online.

Breckyn: Well, so on the topic of Jane Austen and the visual arts—this takes us a little bit off track, but I think it's just so cool. You spearheaded a project called What Jane Saw, which I think you mentioned at the beginning. It's such an amazing online resource. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

Janine: So, whatjanesaw.org—but you can just do What Jane Saw, and even my name, whatever, and you'll get it as—should be your first hit—is a website that creates two visual blockbusters that—museum blockbusters—that Jane Austen must have attended. We know she attended the one in 1813. I think she attended the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery before that in that same building as well. It was a seven-minute or so walk from Cork Street where she visited in the 1790s and visited again in May of 1813. And she saw at that time the Reynolds exhibition, the Sir Joshua Reynolds retrospective that was in the British Institution in 1813. And yeah, I and a team of really cool and talented students recreated that, and professional staff members at UT recreated it online so that you can click on all the pictures that she saw and learn a little bit about them and see—walk in her footsteps, if you will. We're working on a 3D version of it as well at the VisLab at UT, the Texas Advanced Computing Center.

Breckyn: Yeah. And you can just see it all on the walls. And then you can walk through different doors and see which paintings would have been on the wall in which order. It's a really cool resource. And is that the one—

Janine: It's free, and you click through.

Breckyn: Yeah. Where Austen said that she was looking for Mrs. Darcy and Mrs. Bingley.

Janine: She was looking for Mrs. D. and Mrs. B. In the galleries that day. Yeah. And she didn't find them. But this allows you to see what she was looking at and what kind of celebrities that Sir Joshua Reynolds painted she thought she might find Mrs. D. and Mrs. B. Among.

Breckyn: And in a couple of months, we have an episode coming up with somebody— Christine Kenyon-Jones talks about Byron, Lord Byron and Jane Austen, and he attended that gallery as well.

Janine: He attended the opening. He attended the opening, and so did Sarah Siddons, the famous actress.

Breckyn: It was a big event.

Janine: Huge, huge. Royalty attended it. And yeah, and so Austen and her brother went to the gallery. And it's an opportunity to see what she saw. And the only way to recreate that experience was digitally. And so, I had a great PowerPoint that I thought answered all questions, and a friend said, look, this should really be a website. And I said, oh, no, you don't understand. I'm an academic. I write books. I don't do websites. And he said, well, you work at an institution that has 52,000 people. There might be someone there who has that skill. So indeed, in the end, we partnered. And it turned out to be a way of reaching a completely different audience with Austen. And a lot of people are interested in Jane Austen whose interests are also digitally oriented, and who use tools, tools of the future to time travel to the past. And that was the appeal of that particular project.

Breckyn: Right. Yeah. It's collaborative. It's interdisciplinary, it's all those big buzzwords that they love at universities. So, people should definitely look at it if you're doing any research around Jane Austen, or visual arts, or anything like that. It's a really helpful resource.

Breckyn: Well, thank you so much for coming on the show today, Janine. This has been wonderful.

Janine: You're welcome.

Breckyn: Your article on this topic is going to be published in Persuasions On-Line in December of 2024 of this year. So people can look forward to that. What's the title of the article?

Janine: The title of the article continues an article called "Cassandra and the Art of Copying" in the Jane Austen Society Report just this past month. So that's the UK article. And then with those two further examples, "More about Cassandra's Art of Copying" will come out in Persuasions On-Line for Jane Austen's birthday. And then I have this—the spring surprise.

Breckyn: Oh, tell us. Yeah. What are your other Austen-related projects in the works?

Janine: The spring surprise is a graphic novel, speaking of art, about Jane Austen. So it's a graphic biography, called The Novel Life of Jane Austen, and it'll come out in April of 2025, illustrated by Isabelle Greenberg, an award-winning artist and graphic novelist of her own. And, yeah, we teamed up to do something yet different again. And it was—these are projects to be—it's a privilege to work on something like that, so it's been really fun in the making.

Breckyn: Graphic novels are so hot right now. So, that's . . .

Janine: This one will be even hotter.

Breckyn: I'm so excited. And where can listeners go to learn more about your other work? Do you have a website or . . . ?

Janine: I do not have a website, to my shame. I am keeping the next project all to myself until it's ready to be launched. But the What Jane Saw project is the one you can go to. And of course, you can go to Amazon and see all the books that I have on offer about Austen.

Breckyn: Well, thank you so much, Janine. This has been a fascinating discussion.

Janine: It's been really fun. Thank you. ![]()

Breckyn: Okay, listeners, fall is a busy time of year, so we have a few JASNA news shorts and reminders for you this month. First up, the winners of the 2024 JASNA Essay Contest have been selected, and we're delighted to share their outstanding work with the world. We asked students to debate the question, "are Jane Austen's novels still relevant after 200 years?" And we received more than 500 entries from high school, college, and grad school students in the US, Canada, and 34 other countries, making this the biggest response ever. For more on the contest results and a link to the published essays, go to our announcement in The JASNA Post news blog on our homepage, www.jasna.org.

Attention, all teachers, librarians, and reading program leaders working with students in grades K through 12. There's still time to apply for a free Jane Austen Book Box to use in a class or reading program of your own design in the U.S. Or Canada. We're currently accepting applications for the 2024-2025 school year and for 2025 summer programs. Book Boxes are awarded on a first-come, first-serve basis until our program funding is gone, so the sooner you apply, the better. For more information, an application form, and a little inspiration from past recipients, visit the programs web page at jasna.org/programs/jabookbox.

If you didn't register for the 2024 AGM in Cleveland, but you'd like to attend virtually, it's not too late to sign up for the Live Stream/Virtual Option. As a virtual attendee, you can watch all five plenary speakers live: Amanda Vickery, Peter Sabor, Patricia Matthew, Thomas Keymer, and Susan Allen Ford. You'll also have access to 10 breakout sessions (5 live and 5 recorded), and Friday evening's special session featuring fashion historian and previous podcast guest, Hilary Davidson. And you'll have 60 days after the AGM watch recordings of all these presentations. The live stream registration deadline is October 11th. Some spaces remain for in-person attendance as well. For more information and to register, visit the AGM website at jasna.org/cleveland2024.

And as a last reminder, JASNA has started celebrating Jane Austen's 250th birthday next year a little early by offering free student memberships now through December 31, 2025. To sign up, visit our membership page at jasna.org/join.![]()

Breckyn: Now it's time for "In Her Own Words," a segment where listeners share a favorite Austen quote or two.

Betsy Groban: Hello, it's Betsy Groban, proud member of the Massachusetts chapter of JASNA. I couldn't pick just one, so here are two of my favorite contrasting Austen quotes. Don't worry, they're short. The first is from Northanger Abbey when Catherine Morland's neighbor, the good-humored Mrs. Allen, invites Catherine to accompany her and her husband to Bath. Mrs. Allen is aware that "if adventures will not befall a young lady in her own village, she must seek them abroad." The second quote, expressing an opposing viewpoint, is from Emma when the unlikable Mrs. Elton declares, "Ah, there's nothing like staying at home for real comfort." I love these two quotes because they demonstrate, once again, the multitudes that Austen's novels contain, the stark differences in her meticulously-drawn characters brilliantly revealed through their choices and their lives.

![]()

Breckyn: Well, that's it for this episode. Thanks for listening, Janeites. If you're interested in joining the Jane Austen Society of North America or learning more about its programs, publications, and events, you can find them online at jasna.org. That's J-A-S-N-A dot org. Join us again next time, and in the meantime, I remain yours affectionately, Breckyn Wood.

[Theme music]