For many people, there are few things as enjoyable as reading a favorite author’s works or watching a favorite show, but we might not grasp the recuperative effects of reading fiction and viewing films or television shows until we face trying times, such as war, convalescence, or even a global pandemic. For over a hundred years people have been advised to turn to Austen for support, so as COVID-19 spread it is not surprising that people sought out Austen’s novels and adaptations for entertainment, community, and self-exploration. In reading Austen’s fiction during such times we can cultivate what occupational therapists call an “active self” that, as Lena Mårtensson and Christina Andersson explain, “compris[es] meaning in the form of doing, being, becoming, and belonging” (63). Reading is an activity that “fill[s] the gap” when a “substantial part of life is missing” because it “fulfil[s] the ordinary self-image of a reader” and prevents us from feeling trapped (65). By identifying with Austen and her characters, we can better understand our feelings about seclusion and focus on ways to cope with forced isolation. Mårtensson and Andersson remind us that “reading fiction may be seen as an opportunity to achieve a state of being by becoming absorbed in a fictive world”—an escape—but it “may also lead to gaining the social role as a reader, with its relevance for belonging in contexts where reading fiction is a key for inclusion”—such as in book groups and fan clubs (63). Turning to fictive worlds can improve mental and physical health by helping people connect with a range of feelings, from a sense of normalcy and capability to refuge and affiliation (68).

We can link Austen to this therapeutic model, for reading, watching, and writing about Austen works can lead to personal catharsis, insight, and resilience as well as group solidarity. In part, these effects occur because Austen’s fiction shifts the “focus to worlds outside a troublesome reality,” which may allow readers, viewers, and writers to better cope with pain and anxiety and feel capable of functioning in both a meaningful private and a public sphere (65–66). Austen’s plots provide a welcome escape from reality while also helping us both better understand ourselves and the people in our lives and handle as best we can what life throws at us. During the pandemic, for example, many people have spent too much time isolated from family, friends, coworkers, and even potential companions; for others the pandemic forced us to spend more time with our loved ones than perhaps we ever imagined or wanted. Whether we felt isolated from other people or even from our own active selves or felt the desire to escape our remote, stay-at-home routines, turning to Austen during this difficult time made it easier to process the effects of the pandemic on our lives and, through this universalizing experience, to empathize with Austen’s characters as well as fans across the globe.

Of course, this connection with and through Austen is nothing new. For at least a hundred years people have realized the therapeutic effects of turning to Austen in tough times. Perhaps the earliest example of a story describing Austen bibliotherapy, Rudyard Kipling’s 1924 “The Janeites” reminds us that there is no better cure for what ails you than to turn to “Jane when you’re in a tight place” (52–53). Kipling’s characters show the value of reading Austen’s writings during an absence of normalcy and a need for affiliation. Austen’s characters provide common ground for talking about the world and real people, with character names and plots equated to insider intel. The soldiers name weapons after Austen characters, and one experiences catharsis by making fun of an aunt and a nurse by calling them Miss Bates, thus implicitly identifying with Emma. Austen’s books become the soldiers’ companions, helping them feel connected to others, even to feel like special members of a secret society. Their belonging comes from participation in a Janeite society, a condition that applies to many of us today in Austen fan groups and societies like the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA). For these characters, as Mary Favret claims, reading Austen’s novels is not merely “an escape from but training for the demands of world war.” Marilyn Francus likewise confirms that their “discussions of Austen provide an oasis of sanity amidst the chaos of war,” while Janine Barchas and Kristina Straub insist that Austen “represents an unlikely means of uniting people in a common cause across lines of class and gender, even at times of wartime crisis.” We see evidence of this affiliation when a Kipling character proclaims: “Gawd! What a circus you must ’ave been,” and another remarks, “It was a ’appy little group. I wouldn’t ’a changed with any other” (50).

While Kipling draws on bibliotherapy to fictionalize living through war, this tactic is not merely fictional. Doctors prescribed Austen’s novels to soldiers during and after World War I due to what Claudia Johnson calls the “rehabilitative” nature of Austen’s writings on “shattered minds,” and what Favret likens to “restorative therapy” (Johnson 33; Favret). Lee Siegel too writes of “shell-shocked veterans” who “were advised to read Austen’s novels for therapy, perhaps to restore their faith in a world that had been blown apart while at the same time respecting their sense of the world’s fragility.” Writing in 1998, Siegel clairvoyantly argues that in our own time we “may be drawn to Jane Austen for a similar reason”—little could he know that in 2020 we would find ourselves in a year-long global pandemic, feeling shell-shocked. David Owen’s “Conscripting Gentle Jane,” which also addresses World War I soldiers’ directions to read Austen’s novels, has called this prescription the “Austen treatment.” In this essay I address how reading, watching, and writing about Austen’s world can act as a balm that heals wounds and offers a path to both personal restoration and communal affiliation. Turning to Austen can aid us in a variety of traumatic situations, but especially when we are, like Kipling’s soldiers, in a “tight space” and feel cut off from the world and our past selves.

Approximately a hundred years after soldiers in World War I were reading Austen, here we are again needing the Austen treatment. Incidentally, about the same amount of time has passed since another global pandemic, the Spanish influenza. Francus might call this treatment “Austen therapy,” which in her research on early twenty-first-century adaptations shows that readers “turn to [Austen] for respite from their lives, as a kind of therapy.” Austen’s characters and plots have similarities to our lives that allow us to contemplate our current situations, yet their differences afford us the distance to enjoy escaping from our own world for the amount of time it takes to read a book or watch a film. Winston Churchill records a well-known Austen escape in his letter documenting self-prescribed Austen therapy. When he was recovering from pneumonia in 1943, Austen helped Churchill regain his sense of self. He states that in his convalescence he felt disconnected from himself: “it was like being transported out of oneself.” In his recovery he was instructed not to work or worry, so he “decided to read a novel” (actually, to have his daughter read one to him): Pride and Prejudice. Churchill enjoyed the “calm lives” of Austen’s characters and saw them as free from the stresses of war and living in a world for which the biggest problems concerned “manners” and “natural passions” (376–77). Churchill’s account is reminiscent of a 1943 London Times article comparing reading Austen’s novels to the “drowsy hummings of a summer garden” that could drown out the “hummings” of war planes “overhead” (Favret). As Rebecca White suggests, these examples of Austen bibliotherapy reveal a “duality” that “foretells the merging of memory and modernity, past and present”—Regency Derbyshire and war-torn England (489).

Even though Austen’s world is not as calm or drowsy as these two accounts imply, people read Austen’s writings when seeking comfort and take up the Austen treatment beyond times of literal war. Rachel Cohen’s “Living through Turbulent Times with Jane Austen” describes how she turned to Austen at a time when her father was dying from cancer. Cohen shows the signs of bibliotherapeutic insight as she argues throughout the article and in her recent memoir Austen Years that in reading Austen’s work she could reflect on her relationship with her father. As Cohen reminds us, books “have more layers than they can quite contain,” and “this is part of what makes a book a place that a reader can return to at different times over the course of a life” (“Living”). Helen Palmer’s Literary Traveler blog post captures this element, especially the act of returning to a book, in recounting her harrowing experience with dengue fever and confinement. In her convalescence she “devoured more and more Austen, turning from Persuasion to Northanger Abbey and Mansfield Park, then re-reading the others.” Although the act of reading novels was important, the act of re-reading them is as noteworthy. When it comes to the Austen treatment, repeat encounters amplify the benefits.

Churchill, Cohen, and Palmer are not alone in self-prescribing and writing about Austen therapy during medical duress. During my breast cancer treatment, I gave myself the Austen treatment because I needed it to hold on to my active self. I not only listened to her novels on audiobook, but I also kept up with my Austen scholarship and wrote about her in my cancer memoir because writing connected me to my pre-cancer life, gave me a sense of purpose, felt cathartic, and offered me insight into my own experience. In convalescence the Austen treatment was an excellent remedy, for, like Cohen, I found in Austen and her characters uncanny parallels to my life. Through Austen I contemplated the transience of life and how a serious illness can stop you right in your tracks.

Having completed my term as the JASNA International Visitor during the bicentenary of Austen’s death, a year before my cancer diagnosis, Austen’s plight was on my mind. I found myself identifying with her not only as a writer but also a character in a cancer story. Cecilia Pettersson’s essay on women and bibliotherapy reminds us that in sustained periods of isolation, people turn to stories for two reasons: to recognize and to forget themselves. Pettersson says, “Recognition can mean identifying with a character, which has gone through similar problems or difficulties as one’s own, for example, the loss of a loved one or the experience of cancer. But it can also be a matter of recognising oneself on a more general existential plane, in a character who is struggling with a problem” (53). I found myself in a constant state of recognition with Jane Austen, my doppelgänger. Like Austen, I felt my life slipping away. She died at forty-one—I was shocked to learn that Carol Shields speculates that Austen might have died from breast cancer (173–74). I was forty-one wondering if I would make it to forty-two and outlive Austen. I identified with Austen as a writer, too, for I understood, as she did, that writing bolsters an active sense of self, especially when facing death. In writing at the end of her life, she was mindful of her imminent demise, but she kept writing.

Thanks to Austen I survived cancer treatment, but two years later I have found myself forced into isolation and seeking solace from Austen again. This time, however, a global pandemic hit the pause button for everyone. During the pandemic my Austen treatment has included streaming the new Emma; attending digital celebrations sponsored by Drunk Austen, Chawton House, and JASNA; reading and reflecting on passages from Austen’s novels (thanks in part to Natasha Duquette’s 30-Day Journey with Jane Austen); and especially writing this essay.

Many online writers have told readers to pick up an Austen novel to get through this tough time. As a Country Living article claims, “reading classic novels is better for your health than self-help books: time to dig out that Jane Austen classic.” The article cites a study that “discovered that reading classic stories could send ‘rocket boosters’ to the brain and help those suffering from depression, anxiety, chronic pain and dementia” (Walden). Pride and Prejudice to the rescue: it is “time to dust off your Jane Austen classics,” the article advises. That sounds like bibliotherapy. Zoe Gilling, quoted in the article, agrees that “great” literature “has the power to touch diverse people and illuminate what connects us. It can help with inner life, mental health, soul troubles and make us say, ‘I never knew anyone but me felt that.’” It turns out that a lot of people have felt this way about Austen’s writings, and the turn to her work during a pandemic marks a universalizing experience. Although some pandemic readers seek dystopian literature to better understand their emotions, PBS recognizes that not everyone is “finding solace in books that ask dark ‘what if’ questions—some . . . take comfort in the novels of Jane Austen” (Vinopaul). An escape from 2020 is precisely what many of us have needed in these difficult months. The Regency era’s idyllic landscapes, beautiful estates, elegant attire, wit and humor, and, importantly, a world without a pandemic offer the perfect distraction.

Austen’s world, however, holds up a mirror to ours, and people have identified with her characters’ life-threatening maladies, quarantines, and social distancing. It seems that we share the troubles faced by Marianne Dashwood, Jane Bennet, Tom Bertram, Harriet Smith, Louisa Musgrove, and more; some of us might even identify with hypochondriacs Mr. Woodhouse and the Parkers as we panic about coronavirus. If Austen’s characters can survive sickness and seclusion with grace, surely we can too. Right? One of the things we admire about Austen’s characters, Janice Hadlow reminds us, is their resilience. Researchers at the Mayo Clinic argue that “self-directed stress management” and resiliency training help patients divert negative thoughts and interpret experiences positively (Sharma et al. 250). Although the study’s subjects did not read Austen, the findings suggest that reading a good book correlates with resilience, and all of us need that quality to survive months of uncertainty and social isolation.

When we face hard times, Hope Whitmore asserts, “novels and stories tell us that this has all happened before, in a different time, with different names but similar narratives. They tell us that it’s OK to be scared, to have complicated feelings, to feel a bit lost, and they remind us that we are human.” This outcome of bibliotherapy is universalizing: novels “teach us about the world, ourselves and one another” and “give us [hope] for the world to come” (Whitmore). Yet “we wouldn’t return to [Austen] again and again if all she had to offer us was an agreeable candy-colored fantasy,” Hadlow recognizes. Rather, through contemplation and humor, Austen offers timeless problems to think about.

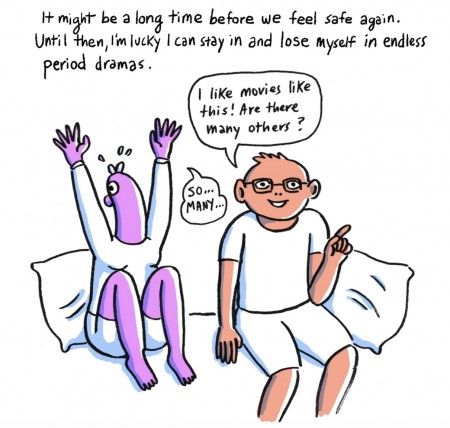

A number of Austen-themed articles and posts appearing during the pandemic have used humor to address isolation, some wittily imitating Austen’s “and” novels to extend the comparison. “Sense and Social Distancing” appears in more than one title, and Lisa Hanawalt’s New Yorker comic “Pride and Pestilence” illustrates how in difficult times people “search for comforting things,” like the 2005 Pride and Prejudice, “to watch while social-distancing.” Still, humor also isolates real concerns, for Hanawalt proclaims, “The pandemic is many of my worst fears come true, and it’s too much to process day-to-day.” It is an “invisible killer” that has made us feel “powerless.” But in the end—as shown below in the last panel of the comic— biblio- and cinematherapy help us cope with “anxiety and boredom.”

For Hanawalt, and many other people worldwide, “fictional romance is [an] escapist distraction from this tragedy.”

Fiction and humor are also what many of us need to get through the monotony of a stay-at-home regime. As Devoney Looser reminds, on “Blursdays”—which is every day when you stay home all of the time—we check “very boring email” and “paralyzing coronavirus news.” However, we also laugh. A lifetime reader of Austen, Looser has to chuckle at comments she reads from “housebound, internet-connected people who say they’ve never understood the confined lives of Austen’s heroines better than they do now.” She laughs at Austen, too, who once wrote in a letter on the Peninsular War, “How horrible it is to have so many people killed!—And what a blessing that one cares for none of them!” (31 May 1811). As Looser recalls, “It’s a line that few of us are likely to be able to find funny these days, although surely Austen, a wartime author, was also just trying to find ways to laugh and get through the narrowest, darkest days?” Like Looser, we probably find ourselves asking if it’s appropriate “to laugh, even darkly, during a pandemic,” but I think Austen would say yes. Dark humor is cathartic, and beyond that, Looser says, we have to “figure out what in the world ‘resilience’ looks like in daily life”—including our ever “evolving, confined relationship to our home (not to mention to space and time).” Perhaps humor and resilience are the only ways to survive a pandemic.

Like Looser, people have been questioning, as a Time article states, “what Jane Austen can teach us about staying home” (Bruner). The piece provides some handy advice: enjoy being a homebody and reading books. Likewise, JASNA president Liz Philosophos Cooper encourages members to find inspiration in sitting with Austen. For Cooper, Austen’s words “every bad day may be the last” (from a letter of 13 March 1816) come to mind as she hopes that at some point there will be a vaccine. In the meantime, Cooper believes that “we can use [Austen’s] example to stay at home, do something creative (however large or small), and help others” (1). Doing something creative and helping ourselves are certainly trends in Austen-themed writings published during the pandemic. “The Guide to Jane Austen Social Distancing” relates Austen characters’ activities—such as only leaving the house to take long walks and “essential trips”; “suddenly wearing gloves, writing letters to far away friends, and taking on unique hobbies”; “maintain[ing] a respectable distance of at least six feet” while in public; and skipping large gatherings like parties (or balls)—to our own pandemic habits (O’Keefe). The article’s author maintains that these behaviors not only represent “doing your part” to avoid spreading coronavirus but also suggest that you are an Austen heroine.

Not everyone wants to be that kind of Austen heroine or is enjoying this stay-at-home time, though some are finding they have more in common with her heroines than they imagined. Wives and mothers living far too long in lockdown with their families are the subject of many essays. Josephine Tovey’s “Sense and Social Distancing: ‘Lockdown Has Given Me a Newfound Affinity with Jane Austen’s Heroines’” is right to point out that “the works of Jane Austen are having a real moment thanks to the pandemic.” The article recalls the absurdity-cum-reality of the scene in Pride and Prejudice when Caroline Bingley encourages Elizabeth Bennet “‘to follow [her] example, and take a turn about the room’” because it is “‘refreshing’” (56). Tovey “discovered a newfound sympathy—affinity even—for every character battling tedium in that room.” Surely, many of us can relate: “All of a sudden, period dramas have become extremely relatable. Ceaseless hours indoors with your family? Fretting about falling into financial ruin? Feeling an outsized thrill at a neighbor who stops by to visit? There’s an Austen for that.” Tovey speaks to the “inherent suffocation of a life lived almost entirely within the same four walls” and how our experiences in pandemic lockdown are providing us with a “fresh appreciation for why characters like Elizabeth Bennet and . . . Marianne Dashwood find a simple walk so electrifying. It gives them freedom and perspective.” What insight!

Rather than chafing against being stuck with people—even those you love—some have bemoaned being single during the pandemic and compared it to Austen’s novels. Included in the byline of “Sense and Social Distancing” is a summary—“isolated, socially distant, and unable to touch anyone: the single life under COVID-19 is eerily Jane Austen-esque.” The article includes @LibraryLydia’s tweet and draws on Austen films to visualize social distancing in Austen’s time alongside ours:

The distance shown in the meme depicts awkward romantic feelings, but Austen gives us more that feels so contemporary and relevant for many young people. Jessica M. Goldstein (in an article also using the title “Sense and Social Distancing”) groans that because of the pandemic a young woman finds herself in the position of an Austen heroine immobilized precisely when “life really starts to happen”:

instead of getting to travel the world, galavant about with friends, go to a university, maybe get a job so her entire financial future doesn’t hinge on her fiancé’s estate situation, our heroine just . . . hangs out at home. With her parents. And her siblings. And then: She waits. Her life is constrained by an endless list of things she is not allowed to do, like go literally anywhere without it being a whole production, or enjoy so much as a friendly hug with a potential love interest.

This description is not far off from the lived experience of isolation and social distancing, which have forced many people into similar circumstances. Goldstein laments that, if we compare ourselves to Austen’s heroines, “we are trapped in a Jane Austen novel, and it is a nightmare.” Obviously not all identifications with Austen’s heroines are pleasant, but their insightful and universalizing qualities can be valuable.

[M]aybe the real takeaway from these books is to emerge from quarantine with less patience than ever before. Everything you were holding off on doing or saying, all those hands you didn’t hold, all those feelings you kept to yourself—now you’re trapped with them, all those unsaid words bouncing around your brain in your empty apartments. It does not have to be this way! When the vaccinated masses can socialize once more, don’t hold back. Waiting 400 pages to tell someone you like them? In this economy? Absolutely not.

On the bright side, then, there is something positive to learn from being an Austen heroine.

Once this pandemic is over, maybe people will think about the things they took for granted, like being able to go to an indoor public place with someone on date. The pandemic truly has shown how difficult it has been for people to date in 2020, and unsurprisingly “This is What Dating Is Like During the Coronavirus Pandemic” brings Austen into this problem. It shares @kaitlynmcquin’s tweet, which jokingly likens dating in our time to Austen’s:

In 2020 many people found themselves getting all Jane Austen up in here, wherever “here” might have been.

Whether we turn to Austen because we enjoy or bewail identifying with her characters, we do so because of her “ability to create characters who resemble us and others we know by portraying psychological states and interpersonal relationships that her readers easily recognize,” as Wendy Jones puts it. Readers “feel the need to be understood, and Austen signals such understanding through her uncanny powers of characterization. Austen is a brilliant psychologist: She ‘gets us,’ and she gets us right” (Jones). That feeling that an author “gets you” is such a powerful one, and it is likely the reason so many people who need a refuge from the world or want to find a way to process what is happening to them turn to Austen.

Reading her novels, watching adaptations, and writing about them in texts as small as tweets and as large as memoirs give us the means to take a break from our lives, understand them better, and connect with others who may be experiencing something similar. In 2020, a global pandemic, seclusion, and distancing generate the need. In the past, war or medical convalescence might have done so, and in the future, it might be something equally isolating. Whatever the case, the Austen treatment is one that helps us cope with our circumstances. When posed the question asked by the author of a NovelTea Tins Facebook post—“Is Jane Austen anyone else’s therapist?”—I say yes. Austen is our therapist right now and, as Amber Brock’s tweet suggests, the medicine we need, stat: