Preeminent Austen scholar Deirdre Le Faye died on August 16, 2020. Deirdre was responsible for work that has redefined our sense of Jane Austen’s life, family, and world. Or, as Janine Barchas puts it,

None of the rest of us could claim what we claim or go where we dare, if she had not done all the heavy lifting of locating and transcribing those letters and providing that foundational Chronology. Once upon a time, Jane Austen needed a male champion with Oxford street creds, because then only men in certain circles could wake an author from the sleep of history. R. W. Chapman championed her admirably. But Deirdre Le Faye has been her true scholar, showing Janeites what patient discoveries in the archives look like.

Having left school at the age of sixteen, Deirdre began her life’s work as an amateur in the truest sense: researching Jane Austen and her family while working full time in an administrative position at the British Museum. Her achievements are many and significant: in 1989 she published a substantial revision of William Austen-Leigh and Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh’s 1913 biography, Jane Austen: Her Life and Letters. A Family Record. Further work led to an even more substantially developed and revised version—now, as Deirdre said, one hundred percent her own—published in 2004 as Jane Austen: A Family Record. Deirdre edited the third and fourth editions of Jane Austen’s Letters (1995, 2011), the notes to which provide a vividly detailed picture of the arts and letters of the time, the Austen circle, public figures, politics, and historical events. In 2006 her Chronology of Jane Austen and Her Family, extending from 1600 to 2003 and filling almost eight hundred pages, was released. As she told Linda Slothouber, that work “made me feel like the Recording Angel, writing up all the daily doings of the Austens and their friends & relations.”

And there were many other publications—too numerous to name. Two rich insights into women important to Jane are Jane Austen’s “Outlandish Cousin”: The Life and Letters of Eliza de Feuillide (2002) and Fanny Knight’s Diaries: Jane Austen through Her Niece’s Eyes, a version of which was published in 1986 as Persuasions Occasional Papers No. 2 and then in 2000 (in an updated version) by the Jane Austen Society. Among her other books, perhaps my favorite is Jane Austen’s Country Life, which provides a richly illustrated picture of all things rural, of the rhythms of the country that lie behind Jane Austen’s novels and letters. There were many articles and notes in journals such as the Jane Austen Society Report (now available online), Review of English Studies, Notes and Queries, Book Collector, and Times Literary Supplement. It’s difficult to find adequate language to define the importance of Deirdre Le Faye to those who care about Jane Austen.

Deirdre often lamented “the amount of misinformation about JA in print” and was interested in disseminating further the research that had been done. She was blunt about her disagreements over facts and their interpretation. (See, for example, her article on the Rice portrait in this issue’s Miscellany.) As Julienne Gehrer testifies,

Deirdre Le Faye was tenacious in her pursuit of knowledge and unashamedly intolerant of sloppy scholarship. Although her pointed criticism became legendary, she quietly and generously mentored a new generation of Austen scholars. Having collaborated with Deirdre for her final three years gave me feelings of unique privilege followed by immeasurable loss.

Linda Slothouber was one of that new generation of scholars.

Deirdre was incredibly generous with her time, knowledge, and resources. Her research tips and comments on my work-in-progress were invaluable, and she sent me books and articles she knew would be useful to me. For years afterward, we carried on a correspondence, exchanging little nuggets of biographical information. Her emails revealed her unremitting research, and also how much she enjoyed every tiny find about the daily lives of people long dead. It reminds me of Jane Austen’s line, “You know how interesting the purchase of a sponge-cake is to me.”

And those qualities were there even as she knew her life was ending. In May she emailed her correspondents in groups to tell them about her impending death, including some lines from a poem she identified as the work of “that prolific gentleman Mr. Anon.” One of the early recipients supplied the actual attribution to Anna Laetitia Barbauld. For the later groups, Deirdre included the new information, remarking with satisfaction, “That’s what scholarship is all about! And I am grateful for the correction.” When in June she submitted her essay on the Rice portrait, she also lamented the fact that she had new material on Mary Anne Campion that she would not get a chance to write up.

I experienced both Deirdre’s criticism and her big-heartedness. For example, in 2008 she wrote, having “just finished reading Persuasions no. 29, with, as usual, much interest,” singling out a few essays with which she “was particularly pleased,” but then rather sternly identifying “a strange error” in another article. But even in such a circumstance, she responded with generosity. When I wrote back in embarrassment, and perhaps with some defensiveness, stating that of course both the author and I recognized the difference between Mary Russell Mitford and Nancy Mitford and that the error had somehow slipped through all our proofreading, she replied kindly and with characteristic humor:

sigh, these strange errors do manage to evade the most stringent double proof checking, and then stand out in capital letters as soon as the offending text is printed—very mysterious! I have a theory that JA doesn’t really like all the fuss made about her, and the passionate interest in every tiny corner of her lifetime, and so sends out thought waves from whatever cloud she’s sitting on, guaranteed to scramble our eyes, fingers, and keyboards—what do you think?

I’m hoping that Deirdre is now sitting on that cloud too, countering those thought waves for the good of Jane Austen studies. Or, as Julienne Gehrer writes, “I told Deirdre that her keen eye and quick wit would provide good company for Jane Austen. Henceforth, my enjoyment of the great author will be punctuated by a twinge of jealousy for the company she keeps.”

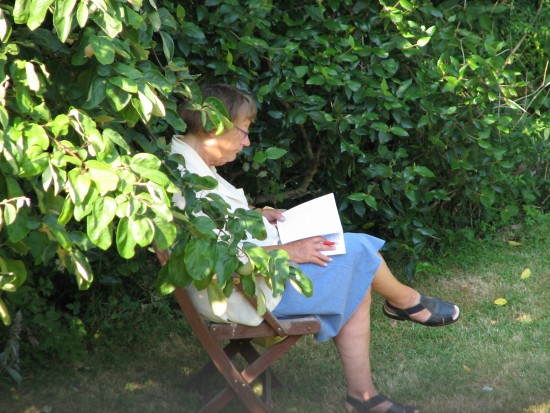

Deirdre Le Faye at Chawton House in 2013. (Photo by Linda Slothouber.)