During the childhood of Jane Austen and her siblings, Enlightenment and Romantic notions of the nature of childhood, human rights, liberty, and related concerns let to dramatically new ideas of how to raise and clothe British children. English parents were beginning for the first time to dress children beyond toddlerhood in garments specific to childhood rather than in essentially miniature adult styles. The changes were rapid: what James Austen (born in 1765) wore from toddler years through young adulthood was probably quite different from what his baby brother Charles, born in 1779, would have worn. While Cassandra and Jane were growing up, their white muslin dresses were being worn by increasingly older girls and finally by adults. What can we surmise about how the Austen children were dressed? Examining the numerous family portraits of the time along with a few surviving children’s garments will give us some clues.1

All the Austens of both sexes would have spent their infancy and toddlerhood in virtually the same garments, the infant’s long gown or “slip” and toddler’s ankle-length, back-fastening “frock.” Under the slip went a shirt and stays, the period term for corset.

Figure 1. Infant gown and stays (ca. 1760).

Rhode Island. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Stays were not tightly laced to constrict the torso but were thought to give needed support to the infant body; some used only cording rather than whalebone. The use of stays on infants died out over the course of the century, as a result of changing notions of child-rearing. It is entirely possible that only the elder Austen babies wore them, or that all of them avoided stays in their early years. Infants’ gowns of the 1760s either had a simply pieced bodice, as in the illustrated example, or were made with a series of vertical tucks or pleats to form the bodice, released into the skirt, in which case they were called a slip. (This term is seldom used today, as it gets confused with what we call a slip.) Toddler frocks sometimes used this construction too. These vertical tucks are visible in a number of surviving toddler frocks and infant slips (Figure 2) and in some portraits (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Infant gown or “slip” (1750–1775). Great Britain. |

Figure 3. Joshua Reynolds, Master John Heathcote (1771–1772). National Gallery of Art, Washington. |

Once walking, toddlers required shorter garments. Before being toilet-trained, boys as well as girls were sensibly clad in frocks over a slip. (Costume terms sometimes refer to two or more different garments: in this case, the slip is an under-dress.) As depicted in portraits, these slips are invariably made of white cotton (muslin), but several printed cotton and linen ones survive and were surely common for everyday wear (Figure 4). In the early nineteenth century, Elizabeth Grant remembered wearing “stuff,” i.e., wool dresses, when muslin had all but conquered fashion (qtd. in Buck 204); it seems likely that wool was worn in cold weather throughout this period.

Figure 4. Copperplate-printed linen frock, back view (1771–1780). |

Figure 5. George Romney, Mrs. Johnstone and her Son (?) (1775–1780). |

The frock was usually open down the back from neck to hem, buttoning like the dress worn by Master John Heathcote (Figure 3) or, seemingly more often, tying: ties are visible in many portraits of toddlers in their mothers’ arms (Figure 5). The open center back is evident in quite a few portraits whose subjects’ skirts are visible from the back or are brought around to the front, such as in the Saithwaite family portrait (Figure 6). A few skirts open in front: young John Peyton-Verney’s overlaps slightly at center front and is open below, revealing a white slip underneath as he steps forward to pull his toy (Figure 7). The bodices of his frock and John Heathcote’s show a common bodice treatment worn by boys: two rows of buttons are arranged near center front, and white cord is laced around them down the bodice in a criss-cross fashion.

Figure 6. Francis Wheatley, Portrait of the Saithwaite Family (c. 1785). Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

Figure 7. Johann Zoffany, John, Fourteenth Lord Willoughby de Broke, and his Family (ca. 1766). J. Paul Getty Museum. |

The frock’s muslin may be opaque and worn over white cotton, or more sheer, revealing a colored silk slip underneath. Many sheer frocks after 1770 have woven or embroidered designs, highlighted by their colored slips (Figure 8). Three such frocks complete with their pink, blue, and green silk slips and one of their sashes survive; worn by one of the princes or princesses of Sweden, they have lace and silk embellishments more elaborate than even the dressiest children in English gentry portraits, but give an idea of the dressier frocks (Figure 9). They are constructed with the pleated bodice often seen on infant slips. The wide silk sashes (probably, like silk slips, only worn for dressy occasions and not every day) could also contrast with the slips. John Heathcote’s pink slip is visible, but his sash is blue; these are the most common colors for both slips and sashes. The gender associations of these colors did not yet exist; John Heathcote is not the only boy to wear pink.

Figure 8. Joshua Reynolds, The Hon. Theresa Parker (later the Hon. Theresa Villiers) (1787). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. |

Figure 9. Three embroidered Indian cotton frocks over silk slips (ca. 1775). |

We can imagine all the Austens of both sexes, between the ages of one and about four, looking like the de Broke boys and John Heathcote (Figure 7; Figure 3), the girls without the laced bodice decoration and the boys with or without it. Colored or printed cotton or linen, along with wool, were probably more commonly worn than the finer, sheer white cottons donned for portraits, but sturdy white cotton could be boiled and was less impractical than it might seem. Red “Morocco” leather shoes were almost universally worn by children from about 1760 into the early 1800s. Girls usually wore caps with ruffles and lace (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Johann Zoffany, The Lavie Children (ca.1770).

National Gallery of Art, Washington.

At about four or five, the older Austen boys, like five- and seven-year-old Thomas and Germain Lavie, would probably have started wearing adult suits: breeches with coat and waistcoat, stockings and buckled shoes ensembles (Figure 10). Thomas, sitting on the see-saw, was born the same year as James Austen; Germain is the boy waving his hat. On the other hand, the Austen family may have been one of the “early adopters” of the incoming fashion for boys: trousers, appearing in some portraits starting about 1770, replacing breeches in three-piece suits, with matching waistcoats (often, the coats are somewhat shorter than men’s). If the older Austens did not wear these, the next two boys, Henry and Francis, born in 1771 and 1774, surely did. Trousers and waistcoats as seen in portraits usually match and are often a buff color; the coat is usually darker, similar to men’s coats, which they imitate. By the late 1770s, boys’ shirts generally had ruffled collars that fell over much of the shoulder and extended halfway down the chest, a style that persists into the 1790s (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Circle of John Greenwood (British), The Music Room (ca 1790). DAR Museum.

Essentially contemporaneously, the two-piece trouser suit emerged on the scene, which eliminated the waistcoat in favor of a jacket or tunic buttoned over the shirt. Henry and Francis probably wore something similar to what John Fortnum, born in 1770, wears in his family’s portrait (Figure 12). His embroidered Indian cotton is unusual, but the family lived in Calcutta (Carman 63). Back home in England, these outfits were made of solid fabrics. Early on, the two-piece suits were probably less common than the three-piece, as they were more radically new than simply replacing breeches with trousers. By the 1780s, however, we see countless younger boys in two-piece suits, while older boys have moved on to three-piece ones. It seems probable that Henry and Frank would have worn two-piece suits first, and then graduated to the three-piece trousers before wearing breeches.

Figure 12. Tilly Kettle, Colonel John Fortnum and his Family (ca. 1774). Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, Houston.

Both trousers and jackets, the next garment introduced into boys’ clothing, were garments worn by the lower classes. Trousers were designed for ease of movement, and also solved the problem of keeping active boys’ knee-high stockings up. The Austen boys probably experienced the falling stockings depicted in several portraits such as Lewis Cage’s in 1768 (Cotes). That a portrait would depict such sartorial carelessness (Cage is shown coatless, his waistcoat unbuttoned) reflects the ongoing changes in ideas about childrearing. The 1693 publication of John Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education, in which Locke advocated for play and physical activity and clothes that facilitated them, had gradually affected many British parents’ childrearing. As early as the 1730s, portraits show children playing, and boys’ collars are often open, the first sign of relaxation of their formal, adult-style dress. By the 1760s, boys can appear disheveled and at play, often with kites, fishing poles, or cricket bats. Wearing trousers made sense once such active play was encouraged.

Charles Austen, coming along in 1779, would certainly have worn a later version of the two-piece trouser suit, in which a short bodice and trousers were buttoned together around a wide waistband. A transitional suit in the Colonial Williamsburg collection with Dutch provenance is nearly identical to those in portraits except for not being buttoned together (Suit); other pre-1800 examples survive in pale blue (Figure 13) and a brown vermicelli print (Royal Ontario Museum). This ensemble was at some point dubbed a “skeleton suit,” though the name probably dates to after 1800.2 Jane Austen had no word for it in 1801 when she asked Cassandra (on behalf of their sister-in-law Mary Austen) for a “pattern of the Jacket & Trowsers, or whatever it is, that Elizth:’s boys wear when they are first put into breeches” (21–22 January). (In this context, Austen uses the word breeches to refer to bifurcated garments in general, in contrast to the frock.) Countless boys in portraits beginning in the mid-1780s wear these ensembles, invariably with the deep ruffled collar and often with a decorative sash probably donned only for portraits and more formal occasions. Skeleton suits were often made of “nankeen,” a naturally occurring tan colored cotton originally produced in Nanjing, but later produced by dyeing off-white cotton. There are many colored versions to be found in portraits, however, and those at the Museum of London and Royal Ontario Museum are printed in allover patterns that appear solid at a short distance.

Figure 13. Boy’s printed cotton “skeleton” suit, British (1774–1790). |

Figure 14. John Singleton Copley, Midshipman Augustus Brine (1782). |

So between about 1770 (when James was probably already wearing breeches) and the mid-1780s (when Charles was the age when boys used to don breeches), two new styles for boys had been created to be worn between the frock and breeches. We cannot know which Austen was the first to wear them. Charles, at least, may well have worn all the 1780s versions in succession: frock, skeleton suit, three-piece trouser suit, breeches. Of course, there were variations in practice: some portraits show boys in various garment combinations that defy logical age progression, such as the boys in the Halkett family (Allan). Francis, of course, joined the Navy in 1786 and Charles in 1791, becoming midshipmen in 1791 and 1794 respectively, and they would have worn midshipman’s uniforms in their teens, looking somewhat like Augustus Brine (Figure 14).

As the Austen boys entered their teens, all would be wearing breeches. Only long, loose hair and ruffled shirt collars would indicate they were not yet adults: we can picture them looking something like Thomas Abraham (Figure 15). This speculation is confirmed in part by the 1783 silhouette depicting Edward Austen joining the Knight family (Figure 16). He sports short bangs and loose hair falling to his shoulders; his shirt collar appears slightly shorter than the adults’ and seems to be folded over, but his suit follows adult fashions. (Since he was well into his teens at this point, when all boys would be in breeches, the silhouette provides no clues to how early the elder Austen boys were breeched.)

Figure 15. John Opie, Thomas Abraham of Gurrington, Devon (1784). Yale Center for British Art. |

Figure 16. William Wellings, Edward Austen Presented to Catherine and Thomas Knight (1783). Chawton House. |

What about the girls? Cassandra and Jane Austen, so close in age, may be considered together. By the time they were born (1773 and 1775), girls were wearing the cotton frock beyond toddlerhood but with a pointed waistline and a V-shaped pair of pleats decorating the bodice, echoing the line of women’s bodices and their stomachers (the center bodice panel inserted between the edges of the gown). Sleeves of these frocks, like the toddlers’, were usually folded in a cuff above the elbow, with the pleated shift (chemise) underneath extending over the elbow and ending in a ruffle. Necklines were quite low and were sometimes filled in with a ruffled muslin or lace “tucker.” These three details can be seen in the 1781 portrait of Juliana Willoughby (Figure 17) and also on the younger girls in the Lavie portrait (Figure 10). Like toddler frocks, these frocks were not always made of the white cotton universally seen in portraits; Jane and Cassandra probably spent a lot of time in printed and colored fabrics (Figure 18; Figure 4).

Figure 17. George Romney, Miss Juliana Willoughby (1781–1783). |

Figure 18. Copperplate-printed linen frock, front view (1771–1780). |

It is clear in some portraits throughout the period that some form of stays would have been worn—a smooth conical torso is visible in many cases—but the use of stays on young girls was declining. In portraits of the Austen girls’ childhood years, plenty of girls, especially the younger ones, have bodices which seem to be loosely fitted rather than constructed over stays. Juliana Willoughby painted at about the age of four (Figure 17) looks just as Jane and Cassandra would have done at that age, with a V-pleat visible, a narrow tucker, but no evident stays. Elizabeth Ham, born in 1783, remembered donning “half-boned” stays at age ten (Cunnington and Buck 128); other families would have chosen corded stays for girls. Stays by this time were also evolving to use fewer bones overall.3

The age for wearing frocks rose throughout this period: by 1775, a teenage girl is still in a muslin frock with the V-pleats over a pink slip (Figure 19). By the time the Austen girls were out of toddlerhood, younger girls retained the toddler frock with its looser bodice and straight waistline for some years before moving to the more grownup, V-bodice style worn by Wheatley’s teenage girl. Some portraits show this distinction, with an older sister in the V-bodice and a younger one in the toddler style, such as John Francis Rigaud’s portrait of the Locker children (Sitwell Figure 104). The Austen girls, however, may have graduated directly into the new style, with a drawstring neckline. Around the ages of six to eight Jane and Cassandra Austen may have looked very like Juliana Willoughby or Theresa Parker, but we can also picture them in frocks with drawstring necklines and without the old V-pleat, like the Museum of London’s example (Figure 18). The Austen girls may very well have looked instead like the Wood girls (Figure 20), whose neckline drawstrings tame the gathers that go all the way around their unstructured bodices.

Figure 19. Francis Wheatley, Family Group (1775–1780). National Gallery of Art, Washington. |

Figure 20. Francis Wheatley, Mary Margaret (Pearce) Wood and Two of her Daughters (1787). |

The Wood girls’ dresses have the additional drawstrings introduced into bodices in the 1780s: one at the waist, and a third casing halfway between waist and neckline, a construction that had burst on the English fashion scene in 1782. (The Museum of London’s dress, dated to the 1770s, is transitional, with a drawstring neckline but retaining the waistline seam.) The actress Mary Robinson (known as “Perdita” after her most famous role) wore a white muslin dress sent her by Marie Antoinette, which became “the universal rage” (Byrne 189–90). First called a “gaulle” after a style worn by Creole women in the French Caribbean colonies and scandalously worn by the Queen of France in a publicly displayed portrait (Figure 21), then dubbed by the English fashion press the “Perdita chemise” or “robe de la reine,” it was known eventually as a chemise dress for the linen undergarment it shockingly resembled.4 Made of lightweight white cotton, the chemise dress in its original form was simply a tube of fabric gathered on drawstrings at neckline, mid-ribs, and waist; more drawstrings gathered fabric halfway down and at the end the full, elbow-length sleeves. The single surviving chemise dress of this type, owned by the Manchester Art Gallery, is also open all down the front, similar to a frock’s back opening (patterned in Waugh, Diagram XXV).

Figure 21. Élizabeth Vigée-LeBrun, Marie-Antoinette (copy of the portrait originally titled La Reine en Gaulle, after 1783). |

Figure 22. George Romney, Mrs. Francis Russell (1785–1787). Art Institute of Chicago. |

Countless portraits of the mid- to late 1780s depict English ladies in these voluminous white muslin dresses, a varying number of the drawstrings occasionally visible, with wide sashes like those worn by girls (Figure 22). As we have seen in the Wood portrait, girls wore them too; extant garments survive in this construction (Figure 23). By 1787, the London-based Lady’s Magazine declared that “all the Sex now, from 15 to 50 and upwards . . . appear in their white muslin frocks with broad sashes” (Byrne 192). A few early neckline drawstrings are visible in portraits prior to this, but by the mid-1780s, the multiple-casing style prevailed. Beginning in the mid-1790s, drawstrings at neck and waist became a popular construction for children’s and women’s dresses (Figure 24). As the waistline rose in the late 1790s, there would be no room for a third casing between neck and waist. Dresses with drawstring necklines (and often drawstring waistlines) lasted into the first decades of the nineteenth century. When the Austen girls reached the age when they would traditionally be moving to more formal, adult gowns (about 1790), muslin dresses and dresses with drawstring necklines and waistlines would simply continue to dominate their wardrobe.

Figure 23. Printed cotton frock, American (ca. 1790). DAR Museum. |

Figure 24. “Costume Français: Robe en chemise avec Spincere,” Journal des dames et des modes (ca. 1797–1799). Rijksmuseum. |

The Caribbean connection and neoclassicism are generally cited as design sources of the chemise dress, but since English and Continental children had been wearing white cotton frocks for decades, they should be considered a precursor to the style as well. That children should influence adult styles may seem improbable, as the reverse had been true for centuries, with scarcely an acknowledgment of childhood deserving different clothes. But cultural shifts around the notion of childhood, and of society itself, explain this dynamic.

Marie Antoinette’s adoption of the gaulle was part of her rejection of court formality and protocol; she wore simple muslin dresses (not necessarily always chemise style but much more informal than court dress) in her retreats at the Petit Trianon and eventually even at court (Weber 163). In the mid-1780s, her “petit hameau” was built: a faux peasant village where she and her circle could play at being milkmaids. Rousseau was one of many writers embracing a pastoral ideal, perceiving society as artificial, corrupted by the excessive influence of civilization, and out of touch with a purer, more honest, “natural” existence.5 This ideal had gained new currency in the second half of the eighteenth century, both in France and England, with widespread influence on taste and the arts.

The pastoral ideal was most literally carried out in the garden design. Instead of imposing civilization’s geometry and artifice on the landscape as in the formal avenues and parterres of Renaissance Italian and Continental Baroque gardens, most famously and influentially executed at Versailles and the inspiration for Chatsworth’s Italian garden (Figure 25), designers and their customers preferred the natural effects of a country landscape, under the leadership of Lancelot “Capability” Brown (never mind how much money had to be spent altering that landscape, even occasionally moving un-picturesque villages, to achieve the natural effect) (Figure 26).

Figure 25. Chatsworth. Italian Garden (litho-engraving by Rock & Co., London. 1863).

© Victoria and Albert Museum.

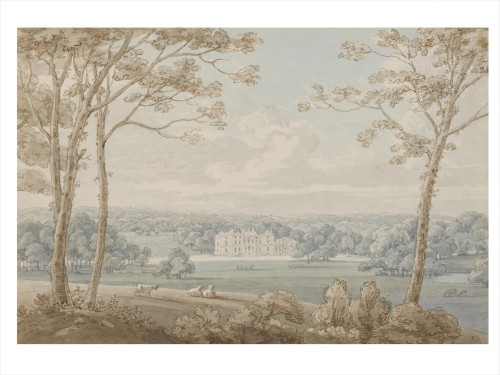

Figure 26. Thomas Sutherland, Sandbeck Park, Yorkshire (1780–1800).

© Victoria and Albert Museum.

Some French aristocrats and intellectuals embraced the English landscape style too, partly in response to Rousseau’s praise in his novel Julie, ou La Nouvelle Héloise (Weber 133). But it was also part of the French “Anglomanie” trend, the pre-revolutionary admiration for English design, manifested in the arts and dress, which was a symbolic and covert expression of alignment with England’s freer society and constitutional monarchy. The Comte de Ségur explained in his memoirs that “our imitation of their dress and manners was not . . . accorded to their taste . . . or superiority in the arts . . . [but to] the desire to naturalize among ourselves their institutions and their liberty” (Ségur 2: 25).

In literature, the idealization of the rural laboring class was summed up by Robert Burns: “‘An honest man’s the noblest work of God’; / And certes, in fair Virtue’s heavenly road,/ The Cottage leaves the Palace far behind” (ll. 166–68). William Wordsworth not only extolled the beauties of nature and wrote in an unaffected manner radically different from the prevailing style, but in his preface to the second edition of Lyrical Ballads he explained his preference for treating “[h]umble and rustic life” by stating that “in that condition of life our elementary feelings co-exist in a state of greater simplicity” (447). And in decorative arts and architecture, elaborate baroque and fussy rococo styles were giving way to more restrained neoclassical design.

Children’s perceived innocence and simplicity put them in the same category as rustics, both being seen as uncorrupted by association with “civilized” upper-class, urban society. Several portrait painters seem to reinforce this ideal by depicting children playing at labor with farm tools (Figure 27).6 In The Prelude Wordsworth too spoke of “[s]implicity in habit, truth in speech” as “the daily strengtheners of [children’s] minds” (5: 421–22). To English and Continental intellectuals and progressives, all these threads came together and became part of political rhetoric. The supposed arcadia shared by children and rural laborers embodied a lost ideal for society destroyed by civilization, and clothing was part of the metaphor. Thomas Paine declared in Common Sense: “Government, like dress, is a badge of lost innocence; the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise” (13).

Figure 27. Johann Zoffany, Portrait of the Blunt Children (1766–80).

Birmingham (UK) Museum & Art Gallery.

In the context of all this idealization of nature and desire for more unaffected approaches to life, art, and dress, it becomes conceivable that lower-class trousers and jackets would be adopted for not only practical purposes but with some echoes of these philosophies, and that women would wear fashions that looked remarkably like children’s.7 Locke’s discussion of children’s need for physical liberty in their clothing was explicitly linked to his notions of personal liberty as a whole, including in political life. To some extent, trousers may have made a deliberate statement of egalitarian beliefs and concern with issues of personal liberty, current among Britain’s liberal Whigs. Many Englishmen were even sympathetic to American colonists in their fight for independence, regarded by Edmund Burke and other Whigs as a legitimate demand for liberties on which the English government was based.

This is not to argue that Mrs. Austen was declaring an affinity for progressive politics by clothing her boys in trousers or rejecting them by hurrying them into breeches. Nor did the Austen girls’ undoubted use of white muslin have any conscious affiliation with the poetic or political idealization of childhood. But it is always worth examining the political and artistic context in which fashions evolve in order to better understand their embedded meanings. Styles develop not only in response to a constant desire for novelty but in tandem with and response to exterior social influences, even if contemporaries were unaware of them. We cannot know the adult Austens’ childrearing philosophies or the conscious thoughts behind the garments chosen for their offspring. But we can surmise that the Austen children were clad in the same garments as other gentry English children of their day, within a short period of each style’s introduction. Contemporary portraits and surviving examples are our best clues to imagining how the young Austens looked in their youth.

NOTES

1It is impossible to include all the portraits mentioned here or all the best and variant examples of the garments discussed. Every effort has been made to use portraits that provide the most typical examples. Those cited but not illustrated are mostly to be found in their museums’ online collection databases; again, examples have been chosen with a view toward easy access. Other useful websites for further browsing include artuk.org; Bridgeman Images (https://www.bridgemanimages.us) the Web Gallery of Art (wga.hu); and the National Trust (UK) collections database, which collects all their sites’ collections in one database at nationaltrustcollections.org.uk. A search for the artists mentioned here will turn up many more examples of children’s and family portraits. Also of possible use is the author’s Pinterest page, which has many boards with all the English, and some American, examples of portraits and relevant garments.

2Charles Dickens’s 1834 description in Sketches by Boz of this garment remembered from his youth is often cited in descriptions of the skeleton suit, and Thackeray mentions one in 1830, but an earlier citation of the term is elusive. It is hard to know what contemporaries in the late eighteenth century called it. As its name seems to derive from its snug fit and possibly its suggestive rows of buttons down the rib area, which were not typical until the turn of the century, the name may well date to the nineteenth century.

3For more on changes in stays and corsets during this period, see “‘A Staymaker of Edinburgh’: Corsetry in the Age of Austen” by Mackenzie Anderson Sholtz and Kristen Miller Zohn in this issue of Persuasions On-Line.

4The story of Marie Antoinette’s adoption of the gaulle, the scandal caused by displaying a portrait wearing one, and how it fit into political and social thought of the time is not relevant here, but it is discussed at length in Caroline Weber’s Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution (150–53 and passim). It is Byrne, however, who documents Robinson’s introduction of the chemise dress and its moniker “Perdita chemise” two years before it was worn by the Duchess of Devonshire, who is usually credited with setting the fashion in England; Byrne also quotes contemporary press that names it a robe à la reine, not de la reine as it is now more commonly called. The original portrait by Élisabeth Vigée-LeBrun is lost; Figure 21 is a copy.

5This trope dates of course to ancient times and is periodically revived; the 1970s saw the Laura Ashley look, and the recent rise of “cottage core” has similar echoes.

6Dated 1766–1770, the boys are toddlers born in 1760 and 1761; even if actually painted later, the work depicts them as they would have appeared in about 1763.

7In the intervening years between boys’ and men’s adoption of trousers, the French Revolution’s glorification of the “sans culottes,” literally “without breeches,” of course played a part, but we here must examine the possible motivations of upper-class English families in dressing children in laborers’ dress a generation earlier.