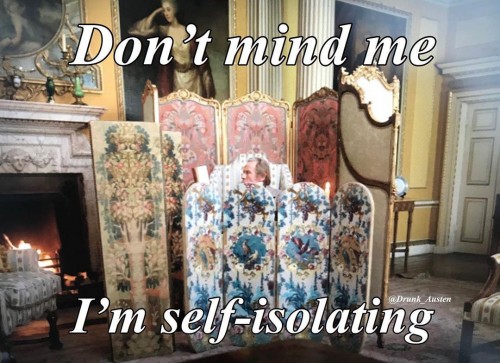

As the COVID-19 lockdown began in March 2020 in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, various internet memes related to Jane Austen’s novels (or the films they inspired) began to circulate online on social media, particularly Facebook and Twitter. The Austen-related memes typically employ words and images—or sometimes words alone—in a humorous way to make a point about the similarities between the situation of Austen’s characters and the situation of twenty-first century Austen readers in quarantine (see Figure 1). The memes circulating on Twitter and Facebook in March, April, and May 2020 testify to how closely twenty-first century middle-class Western life during quarantine resembled the everyday lives of Austen’s heroines: social isolation, dull domestic life and consequent boredom, severely limited physical activity, enforced celibacy for unmarried men and women, and intermittent anxiety about the possibility of contracting or transmitting a potentially life-threatening illness. Deidre Lynch, who analyzes Austen’s reception in eras ranging from the Victorian to the mid-century modern, observes that, for Janeites, “the contingencies of their historical moments mingle productively with their literary appreciations, so that Austen in some sense both produces them—arousing specific enjoyments, consolations, and pleasures in her acolytes—while they in turn are also producing her for us [that is, for Austen scholars], enabling us to read through their eyes and see in Austen’s novels properties and possibilities we rarely if ever suspected were there” (14). The contingencies of this particular historical moment—a global pandemic and consequent lockdown throughout much of the Western world, partially offset by widespread internet access—have inspired in Janeites worldwide what digital communications scholar Henry Jenkins, writing of memes more broadly, calls a “desire to rewrite core stories” (259). Austen fans have produced and reproduced in their online memes a wise and benevolent Austen who offers consolations for their isolation, loneliness, boredom, and anxiety.

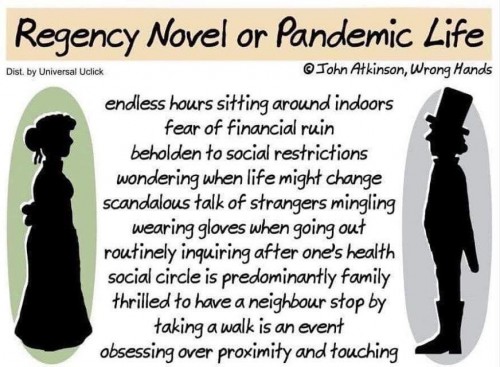

Figure 1

Memes are cultural units—including ideas, tunes, catchphrases, or images—that arise and propagate themselves through imitation. According to Richard Dawkins, the evolutionary biologist who invented the term, “Memes are complex units, distinct and memorable—units with staying power” (qtd. in Gleick). Originally transmitted primarily by word of mouth, they are now more likely to circulate digitally: “As the arc of information flow bends toward ever greater connectivity, memes evolve faster and spread farther” (Gleick). Philosopher David Dennett tells us, “A meme is an information packet with an attitude” (qtd. in Gleick).

Internet memes are multimodal, incorporating “linguistic, image, audio, and video texts created, circulated, and transformed by countless cultural participants across vast networks and collectives,” making them a form of folk media (Milner 1, 40). Memetics scholar Ryan Milner explains, “Understanding their implications for public conversations requires understanding intertextual connections” (2). This essay focuses on internet memes that connect intertextually to Austen’s novels and to the films and television productions based on those novels. Because “memes shape the mindsets, forms of behavior, and actions of social groups,” it is important for us to consider which “shared norms and values” Austen-related pandemic memes construct and perpetuate (Shifman 18, 15).

Analyzing Austen-related memes allows us to examine the ways in which Austen is read by contemporary readers in the midst of a crisis, for it is Austen fans who create the memes (and thus become “prosumers”) and circulate them by sharing and retweeting:

While the words for a post or the image for a meme may come from Austen’s novel or a cinematic adaptation, the content circulated on social media originates with the fan and is created for other fans. This online engagement not only paints a picture of what Austen prosumers find exciting about the author and her novels, but also shows how fans are shaping online Austen culture through the kinds of information they post and share approvingly. (Krueger, “Handles” 380)

While many of the memes cited in this essay use images from the movies to illustrate their point, their creators often incorporate Austen’s words and mocking tone to make the humor effective. Much like Austen’s novels, many of the memes related to her fiction are ironic, critical of social behavior, and genuinely funny.

Only a handful of scholars have examined Austen-related memes or her work’s presence in social media. In a Guardian article titled “How Social Media Helped Me Get Jane Austen on to £10 Notes,” Caroline Criado-Perez has chronicled her experiences organizing a successful Twitter campaign. Camilla Nelson has analyzed memes that reinvent Austen’s Mary Bennet as a postfeminist icon. Misty Krueger has written on the pedagogical value of having students adapt and modernize Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility digitally (“Products”); she has also assessed the significance of Austen’s presence in social media more broadly (“Handles”). No Austen scholar has commented as yet on the use of Austen-related memes about the pandemic and lockdown.

Perhaps the hardest aspect of the lockdown for most twenty-first century humans to bear is the extreme social isolation necessary to limit the spread of the coronavirus. The claim in Figure 2—a meme retweeted more than 9,000 times and “liked” by more than 28,000 Twitter followers—that Austen movies “invented” social distancing constructs Austen (however indirectly and facetiously) as an expert whose wisdom can guide contemporary readers during this crisis.1 As one entertainment journalist explains, “Jane Austen’s heroines embody our lifestyle and offer uniquely positive role models for behavior in an extraordinary time like this” (O’Keefe).

Figure 2

As Valeska’s “Jane Austen Movies” (Figure 2) somewhat facetiously points out, all of Austen’s women experience isolation: “To be a woman of a certain class in Regency England was to be socially distanced by default—isolated in the country-side, living at the pace of the seasons, beholden to restrictions set by others (namely, men)” (Bruner). “‘In a country neighbourhood you move in a very confined and unvarying society,’” Mr. Darcy aptly observes (PP 42–43). For example, Emma befriends the unsuitable Harriet Smith because she is so lonely after losing her governess. Because the abruptly impoverished Dashwoods live in a country cottage and lack a carriage, they depend upon the kindness of Sir John Middleton for most of their social engagements, just as Miss Bates, her mother, and Jane Fairfax would have difficulty socializing without the generosity of their neighbors, such as the loan of a carriage from Mr. Knightley.

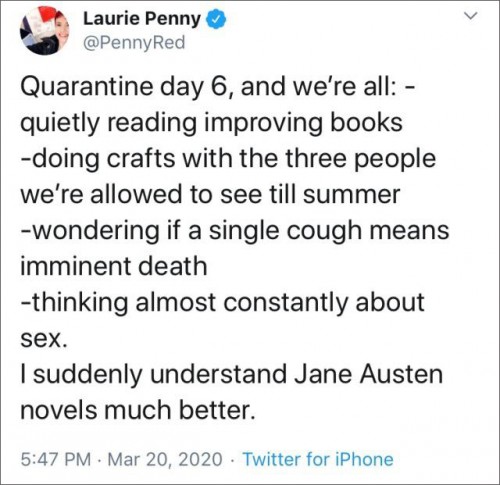

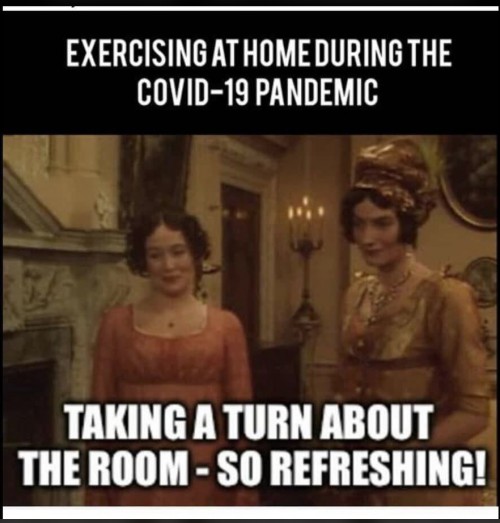

Several Austen-related memes mock the limitations of a dull domestic life— “endless hours sitting around indoors” (see Figure 1). In a particularly comprehensive March 20 tweet, which garnered more than 23,000 “likes” by mid-June, Laurie Penny catalogs many of the similarities between Austen’s time and the twenty-first-century lockdown (see Figure 3). Each of the activities named here has its counterpart in an Austen novel. Her post suggests that the social restrictions thrust twenty-first-century Western society into a situation remarkably comparable to that experienced by every Austen heroine.

Figure 3

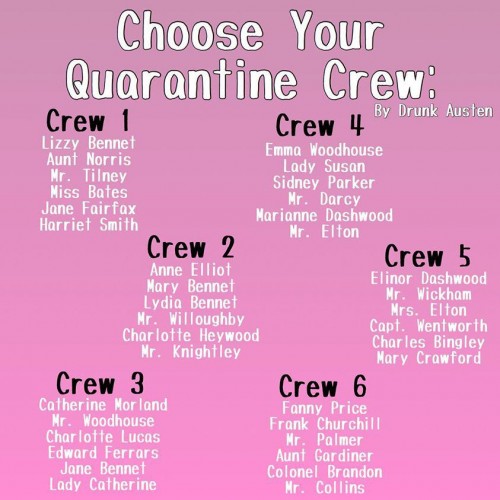

The corollary of their very limited social circles is that Austen’s characters typically spend inordinate amounts of time in close quarters with the same tiresome people. The popular “quarantine house” memes, which ask the audience to choose a house in which to spend time under quarantine, capture that sense of being trapped with a limited number of often very trying individuals, whether under quarantine or in a Regency novel.

Figure 4

In the Austen versions of the meme (see Figure 4, and Drunk Austen, “Choose”), each house contains some attractive companions—Elizabeth Bennet, Mr. Knightley, or Colonel Brandon, for example—and others likely to prove disagreeable—such as Mr. Collins, Mrs. Norris, and Mrs. Elton. The quarantine house meme forces us to acknowledge, with Austen, that any household, including our own, is likely to contain people who are disagreeable and ridiculous, at least some of the time. As a Time magazine journalist writes, “Many of us have been forced into inescapably close quarters with the people we love most—getting reacquainted with one another’s most irritating quirks and wondering how to live under the same roof without losing our minds” (Gutterman). Every Austen heroine learns to master that skill.

Austen clearly disapproves of those who, like Lydia Bennet and Maria Rushworth, incessantly seek excitement outside the home. Writing for Time magazine, Raisa Bruner notes Austen’s “distaste for those who could not be satisfied with staying home, a luxury she could not always afford.”2 Bruner praises the “modest domestic pleasures that Austen’s women know and cherish so well,” such as planning meals and writing letters. As a character like Anne Elliot demonstrates, for Austen, domestic work and emotional labor matter. For as Vera Rubin tweeted during the lockdown, “The economy isn’t ‘closed.’ Everyone is working diligently homemaking, cooking meals, and taking care of their loved ones. It’s just not valued by economists because it’s unpaid labor. Have a great day at work everyone.” What Rubin doesn’t acknowledge in her tweet is that homemaking, cooking meals, and caregiving have traditionally all been women’s unpaid labor. The American men—and it was mostly men—who protested the quarantine by marching on statehouses (sometimes with guns) resented complying with the limitations that would have been common for a woman in Regency England—and that are still common for many stay-at-home mothers of young children. The protestors refused to participate in women’s work and bristled at restrictions that Austen’s heroines (and many twenty-first-century mothers) take for granted.

Figure 5

(Click here to see a larger version.)

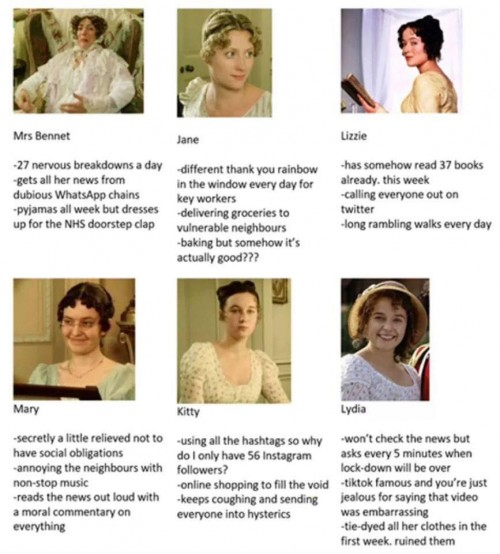

Many of the memes recontextualize Austen’s characters, inserting them into contemporary circumstances to make a point about contrasting responses to lockdown. For example, “Mrs Bennet” (Figure 5) situates half a dozen characters from Pride and Prejudice into today’s pandemic (see also Drunk Austen, “What’s,” and Overstreet). As Mr. Bennet reminds Lizzy, “‘For what do we live, but to make sport for our neighbours, and laugh at them in our turn?’” (PP 364). Laughing with Lizzie’s “Exercising” (Figure 6) recontextualizes Caroline Bingley’s words in Pride and Prejudice to ridicule the extremely limited opportunities for physical activity afforded women during the Regency era, for Austen’s women rarely “exercise” in the twenty-first century sense.3

Figure 6

Although the first page of Northanger Abbey reveals that Catherine Morland enjoys “cricket, base ball, riding on horseback, and running about the country” as a fourteen-year-old tomboy (NA 15), she is the exception; the rest of Austen’s women typically confine their physical exertion to short walks around the drawing room, domestic tasks such as wrangling children, and—weather permitting—long walks through the countryside (preferably without muddying their petticoats). The meme was later transformed to incorporate a photo from the 2005 film starring Keira Knightley with nearly identical text, which suggests that Austen’s words are more significant than the image in this particular meme. Caroline Bingley’s invitation to Elizabeth Bennet to “‘take a turn around the room’” (PP 56) resonated with readers who in some cases were literally proscribed from leaving their homes.

For Austen, reading is a gentle pastime eminently suitable for those convalescing or under quarantine. Captain Benwick reads to Louisa Musgrove as she recovers from her head injury, and Marianne Dashwood ambitiously plans to read six hours a day as she convalesces from a life-threatening illness. Despite understandable difficulty concentrating amidst the anxieties of a global pandemic, many people privileged enough to have seemingly endless free time under lockdown have chosen to employ at least part of it reading. Many Austen fans have not surprisingly chosen to read or reread works by Austen because of what Juliette Wells, in her discussion of how the general public reads Austen in the twenty-first century, identifies as their comforting qualities: “For a wide variety of readers, Austen’s novels relieve the stresses of daily life by affording mental escape” (73).

Figure 7

This escapism is captured in Laughing with Lizzie’s “All of Us After Quarantine” (Figure 7), which recontextualizes Annie Reed and her friend Becky, characters played by Meg Ryan and Rosie O’Donnell in Nora Ephron’s 1993 romantic comedy Sleepless in Seattle. In the film, the two friends rhapsodize weepily over the sentimental 1957 film An Affair to Remember, a romantic melodrama starring Deborah Kerr and Cary Grant. In the meme, it is not the 1957 film but Austen’s novel Pride and Prejudice and its 1995 television adaptation that they find so emotionally moving—specifically Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s recommendations to Mr. Collins in chapter 14 (PP 66), and Elizabeth’s ironic response in the 1995 television adaptation: “A happy thought indeed!” This meme implies that women would read the novel or watch the dramatization so many times during their quarantine that they would have it memorized by the time they escaped from lockdown. The meme constructs obsessive rereading and reviewing of Pride and Prejudice as a form of protective self-care. As Wells explains in Everybody’s Jane: Austen in the Popular Imagination, many readers use Austen’s work this way: “entering Austen’s fictional worlds means leaving behind, and even forgetting, discomfort, worry, and chaos” (74). Or as Rudyard Kipling’s soldier bluntly advises in his short story “The Janeites,” “there’s no one to touch Jane when you’re in a tight place” (140).

Figure 8

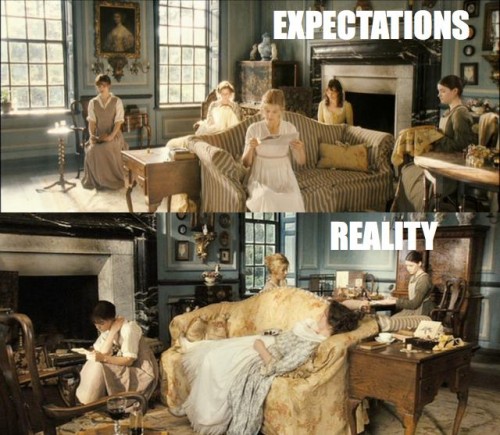

Like many people under lockdown, Emma Woodhouse is forever drawing up lists of improving books to read but never quite manages to read them. The Jane Austen Centre’s “Expectations/Reality” meme (Figure 8) references Pride and Prejudice rather than Emma, but it does capture a comparable gap, and we laugh because we recognize our similarity to Austen’s women in our own failures to live up to our own (perhaps unrealistic) expectations, even amidst the anxieties of extraordinary circumstances. While the meme references the 2005 film rather than Austen’s novel, its pointed irony about human foibles does evoke Austen’s own.

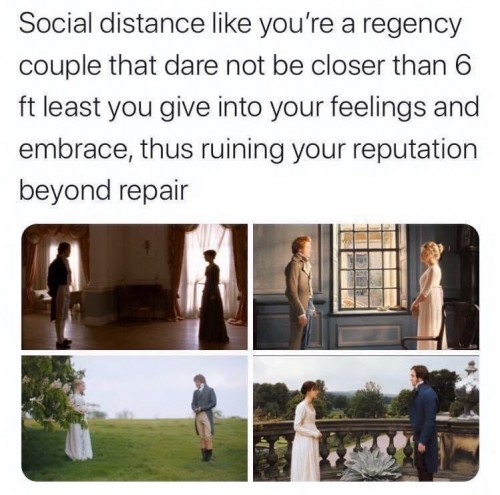

Life under lockdown has required many single adults to experience prolonged celibacy for the first time. As the images in Library Lydia’s “Social Distance” (Figure 9), retweeted more than 26,000 times, would indicate (despite the unfortunate misspelling of “lest” as “least,” which was later corrected), the women in Austen’s novels live under similarly severe constraints, in which young women are permitted to touch potential romantic partners only when they dance or if they become engaged.

Figure 9

Virtually all of Austen’s heroines think about the men available to them, often to the point of unhealthy preoccupation, and several young women—including Lydia Bennet, Eliza Williams, and Maria Rushworth—imprudently run away with sexually attractive (and unscrupulous) men, which suggests that the enforced chastity of the Regency era proved excessively constricting for many women. Twenty-first-century “singletons” have experienced similar deprivation. As one writer bluntly observed in an article for Marie Claire, “we are trapped in a Jane Austen novel, and it is a nightmare” (Goldstein).

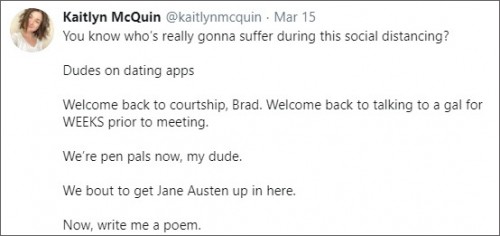

In contrast, however, Kaitlyn McQuin’s sassy tweet about men on dating apps (see Figure 10) suggests that reverting to Regency courtship behavior could be a salutary change for women. That conclusion seems ironic, because Austen’s women characters do not seem particularly powerful. In addition to the limitations already noted, they cannot initiate relationships and must wait to be approached by men, and they are often pressured by parental figures (as Elizabeth Bennet, Fanny Price, and Anne Elliot are) to marry men they don’t love or respect. Retweeted more than 79,000 times and “liked” by more than 484,000 people, McQuin’s enormously popular meme establishes a contrast between dating apps, which give men the power to choose women based almost exclusively on visual appearance and sexual attractiveness, and Regency courtship behavior, in which socially enforced celibacy affords women the ability to judge men’s characters without feeling compelled into a sexual relationship before they are ready. The tweet indicates that requiring men to court women, as they did in Austen’s day, restores to women a certain balance of power in romantic heterosexual relationships.

Figure 10

Speaking of visual appearance and sexual attractiveness, the wildly popular scene of Mr. Darcy wearing a wet shirt in the 1995 television adaptation of Pride and Prejudice is cleverly ridiculed in a reenactment featuring plastic action figures of “Will and Jane” (that is, Shakespeare and Austen) by Janine Barchas (see Figure 11). Barchas, who co-curated the 2016 “Will and Jane” exhibit at the Folger Shakespeare Library, created the Twitter account Pride & Plague, launched March 21; its cheerful memes of the action figures wearing tiny protective masks had garnered the account just under 1,000 followers as of August 2020.

Figure 11

Many Austen-related pandemic memes focused on the challenges presented by the coronavirus itself. The pandemic has provoked (understandable) hypochondria among many, prompting people to overreact to their own minor symptoms. Perhaps because of her own mother’s behavior, Austen ridiculed hypochondriacs: Mr. Woodhouse in Emma, Mary Musgrove in Persuasion, and Arthur, Susan, and Diana Parker in Sanditon all come in for their share of her mockery. Laurie Penny’s “Quarantine Day 6” (Figure 3) similarly satirizes everyone’s hypochondria and very real anxieties about the coronavirus: “we’re all . . . wondering if a single cough means imminent death” (@PennyRed). The creators of the Drunk Austen Facebook account recontextualize a particularly satirical scene of Mr. Woodhouse and his screens from the 2020 film version of Emma (Figure 12) to reframe the present.

Figure 12

Laughing with Lizzie’s “Don’t Keep Coughing” (Figure 13) pokes fun at the concern during the pandemic that any random respiratory symptom (such as a runny nose from an allergy or a cough from the common cold) might be mistaken for COVID-19 and so prompt overreactions from worried bystanders. Kitty’s incessant coughing in Austen’s novel becomes a worrisome symptom when what seems like a mild respiratory illness can kill.

Figure 13

Illnesses are tricky and unpredictable in Austen’s novels. After Mrs. Bennet decides to send Jane to Netherfield on horseback rather than in a carriage so that she will be caught in the rain and be compelled to stay there overnight, Jane sends home a letter to say that she has developed a sore throat and a headache: “‘Well, my dear,’ said Mr. Bennet, . . . ‘if your daughter should have a dangerous fit of illness, if she should die, it would be a comfort to know that it was all in pursuit of Mr. Bingley, and under your orders.’” Mrs. Bennet, unrepentant, responds, “‘Oh! I am not at all afraid of her dying. People do not die of little trifling colds’” (PP 31).

Elizabeth is more concerned than her mother, however, and rightly so, for in Austen’s novels, a host of people develop sudden, life-threatening illnesses, including Mrs. Tilney, Tom Bertram, and Fanny Harville. Marianne Dashwood’s illness, which begins as a cold before progressing to “putrid fever” (SS 330), abruptly becomes so dangerously life-threatening that her mother must be sent for at once. Austen’s sister, Cassandra, lost her fiancé to a tropical fever contracted in the West Indies, and, of course, Austen herself died of a mystery illness, possibly Addison’s disease, when she was only forty-one. Illness is an ever-present threat for Austen’s characters, and she teaches us to be wary of it.

Figure 14

(Click here to see a larger version.)

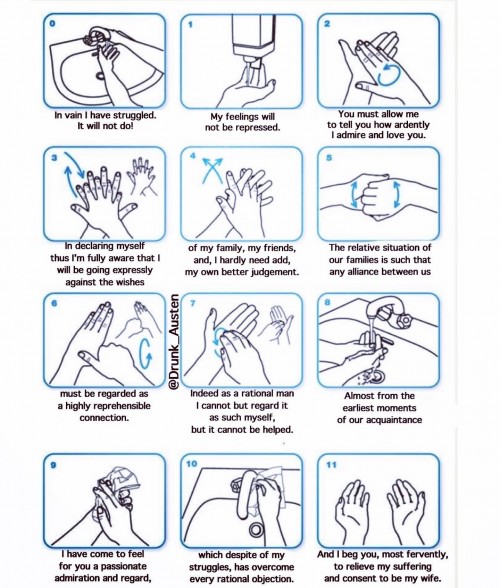

In 2020, one of the most useful precautions anyone can take in preventing the spread of COVID-19 is frequent and thorough handwashing. The memes that recommend washing one’s hands while reciting Darcy’s first proposal (or in some cases, both of his proposals) attempt to distract the handwasher from both health anxieties and tedium by recalling a favorite scene from the novel, complete with a quotation of Austen’s exact words inserted handily into a World Health Organization infographic (see Figure 14 and @Drunk_Austen). The meme constructs Austen as a quasi-maternal figure whose words reduce discomfort, much as a mother might distract her child from the pain of having a splinter removed by singing or reminiscing about happier times in the past.

Figure 15

The second most popular meme discussed in this essay, Hannah Long’s creation (see Figure 15) received more than 274,000 likes and 58,600 retweets. Mocking both Mr. Darcy’s solicitude for Elizabeth and her family and his social awkwardness, Long also satirizes a felt need during the pandemic to ask earnestly about the health of one’s correspondent and his or her family in even the most casual communications, such as random work-related emails to professional colleagues (Steinmetz). The meme evokes the 1995 miniseries rather than Austen’s novel, but Mr. Darcy does make similar inquiries in Austen’s novel (PP 171, 189). Both Long and John Atkinson (Figure 1) capture their audience’s concern for others and their own sense of social awkwardness in making these routine inquiries that had once seemed happily obsolete.

Finally, JASNA’s meme (Figure 16) casts Austen as cautiously optimistic and benevolently wise. Like good scholarship, JASNA’s appropriately tasteful meme emphasizes Austen’s own words and cites the source for its quotation, a letter to Jane’s sister, Cassandra, during their brother Henry’s illness (26 November 1815). Its familiar image of Austen—a “colorized” version of the portrait used as a frontispiece to A Memoir of Jane Austen (1870) by James Edward Austen-Leigh—was inspired by Cassandra Austen’s famous watercolor of her sister (painted circa 1810), both now available for viewing on the National Portrait Gallery’s website. Thoughtful and prudent, this Jane wears a mask, as recommended by various medical authorities, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the U.S. and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control in the United Kingdom and the European Union. But she reassures us that, while taking appropriate precautions, we must nevertheless continue to do the best we can, think positively, and hope for the best.

Figure 16

Based on my own informal surveying of social media, no other author’s work has been the focus of so many pandemic-related memes—ironically, not even the literature of the modernists, who personally survived the worldwide influenza pandemic of 1918, the most obvious historical parallel to this twenty-first-century pandemic. Krueger tells us, “Ultimately, a survey of Austen social media shows us as much about the people who engage with Austen on the web, and to what ends they do this, as it does about Austen and her novels” (“Handles” 379). What do these Austen-related pandemic memes reveal?

Certainly they demonstrate Austen’s enduring popularity in Western culture and a felt need for her continuing presence. As Marilyn Francus observes in “Austen Therapy: Pride and Prejudice and Popular Culture,” “There will always be the desire for more ‘Austen,’ as readers, chronologically and culturally removed from Austen, will adapt and appropriate her life and works to their needs.” In part Austen’s prominence at this particular historical moment reflects the tendency of many people—especially salaried people with white-collar jobs requiring a college education—to read her novels and binge-watch movies and television productions of her work for comfort when under stress (Francus); her novels and the productions based on them are often seen as soothing because they lack violence and have reliably happy endings. Anyone stuck at home trying to kill time has very likely had sufficient leisure to read all six of her novels and watch multiple adaptations. Audiences could not miss the connections to their own lives. As one journalist wrote, “We are all Mr. Hursts and Caroline Bingleys now. These days, I only envy Miss Bingley for having a room large enough to take a refreshing constitutional in. Bully for her” (Tovey).

Austen and her works are frequently employed in these social memes as a form of shorthand to signal a willed emotional resilience in Western culture, which has endured similar forms of deprivation and restriction before. Viewing these comic memes is cheering and distracting. But these memes also suggest to social media consumers that what we have all experienced together is not altogether unprecedented and that—like Austen’s protagonists—we can not only endure but endeavor to find joy in our enforced domesticity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to Debra Bentley and Beth Lindsmith, who helped me find Austen-related memes for this project, and to Julie McDaniel, Rose Tyler, Jean Long, and Susan Allen Ford, who helped me discover and access sources during my research in the midst of a global pandemic.

NOTES

1One of the disadvantages of working with memes is that they become memes by being imitated, which in social media means being shared or retweeted. As a result, “Finding their creator and site of origin is largely impossible, and arguably inconsequential when considering how they resonate” (Milner 15). I have attempted to trace each meme as far back as possible, a feat that is simpler with the prose of tweets on Twitter than with the photographs and other images posted on Facebook. Unless otherwise noted, all of the statistics in this article were verified as of June 17, 2020.

2Biographer Valerie Grosvenor Myer notes that “Jane Austen was never secure financially” and that “[a]s a single woman without money, she was marginal to society” (viii). Her family had a carriage for only a few months of her life, and “[r]espectable women did not travel alone by stagecoach” (60). For the rest of her life, therefore, she was forced to depend on the benevolence of others to travel anywhere too far to walk.

Only after the publication of Sense and Sensibility did Austen briefly have the financial means to travel independently: “The importance to her of this first money she had earned for herself can be best appreciated by women who have endured a similar dependence. It signified not only success, however modest, but freedom. . . . She could give presents and plan journeys” (Tomalin 218). But that was a short-lived exception. As a “poor relation” (Myer 31) for most of her life, Austen had to school herself to find contentment at home.

3It is not clear why Elizabeth Bennet’s nickname is given as “Lizzie” when it is spelled “Lizzy” in Austen’s novel.