Volumes have been written about Jane Austen’s connection to music. Her novels make frequent references to the musical activities, abilities, and preferences of her characters. Jane Austen’s music books reflect the widespread activity and enjoyment of musical amateurs in the early nineteenth century. Here we share perspectives on Jane’s musical world and her activities as well as on her predilections as an amateur pianist—with some clips from our performance at JASNA’s AGM, “Brunch at Chawton: A Jane Austen Musicale.”

![]()

Eighteenth-century conduct books, such as Thomas Gisborne’s Enquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex (1797), recommended that young women of the gentry pursue “ornamental acquisitions” such as dance, music, drawing, and languages such as French and Italian that would provide “innocent and amusing occupations” for herself and her family (80). Naturally, such accomplishments made a young woman all the more appealing for marriage. The countless four hand piano arrangements that date from this period were not utilized simply for the greater exploration of musical art but as a wonderful excuse for a young man and woman to sit very close at the keyboard.

Eighteenth-century conduct books, such as Thomas Gisborne’s Enquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex (1797), recommended that young women of the gentry pursue “ornamental acquisitions” such as dance, music, drawing, and languages such as French and Italian that would provide “innocent and amusing occupations” for herself and her family (80). Naturally, such accomplishments made a young woman all the more appealing for marriage. The countless four hand piano arrangements that date from this period were not utilized simply for the greater exploration of musical art but as a wonderful excuse for a young man and woman to sit very close at the keyboard.

In many homes, the pianoforte was a focal point for social gatherings, family life, and even courting. Hiring a music master to train your daughter showed your secure place in the upper classes—or suggested, at least, that you were trying to move into them. In Emma, when the news breaks that Jane Fairfax has received the mysterious gift of a pianoforte, Mrs. Cole chatters to Emma about the prevalence of pianofortes in contrast to Jane Fairfax’s lack of one:

“It always has quite hurt me that Jane Fairfax, who plays so delightfully, should not have an instrument. It seemed quite a shame, especially considering how many houses there are where fine instruments are absolutely thrown away. . . . [I]t was but yesterday I was telling Mr. Cole, I really was ashamed to look at our new grand pianoforté in the drawing-room, while I do not know one note from another, and our little girls, who are but just beginning, perhaps may never make any thing of it; and there is poor Jane Fairfax, who is mistress of music, has not any thing of the nature of an instrument, not even the pitifullest old spinnet in the world, to amuse herself with.—I was saying this to Mr. Cole but yesterday, and he quite agreed with me; only he is so particularly fond of music that he could not help indulging himself in the purchase, hoping that some of our good neighbours might be so obliging occasionally to put it to a better use than we can; and that really is the reason why the instrument was bought—or else I am sure we ought to be ashamed of it.” (232–33)

But Mr. Cole’s fondness for music is not universal. In Sense and Sensibility, Marianne Dashwood and Elinor go to a musical soiree that included “a great many people who had real taste for the performance, and a great many more who had none at all” (283).

Jane Austen began lessons at the age of twenty, studying piano with the organist at Winchester Cathedral, one William Chard. Family music volumes also contained lessons on the rudiments of music. When the Austen family moved to Bath at Mr. Austen’s retirement, however, Jane’s instrument was sold. At Mr. Austen’s sudden death in 1805, Mrs. Austen, Cassandra, and Jane were left in dire financial straits. Relief came in 1808 when the Austen women were offered a cottage in Chawton, part of the estate of Jane’s brother Edward, where they moved in 1809. The family was not wealthy, but in 1808, Jane reported to her sister Cassandra: “Yes, yes, we will have a Pianoforte, as good a one as can be got for 30 Guineas—& I will practise country dances, that we may have some amusement for our nephews & neices, when we have the pleasure of their company” (27–28 December 1808). Thirty guineas was a significant sum for such a piano in 1808. But, far from being a luxury, for Jane, it was a necessity.

The latter half of the eighteenth century in Europe was a time of transition as far as harpsichords and fortepianos were concerned. The harpsichord, with its plucking action, had been ubiquitous for three centuries. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Italian inventor Bartelemeo Cristofori introduced a keyboard instrument “che fa’ il piano, e il forte” (that makes soft and loud). This innovation of a keyboard action that utilized felted hammers striking strings, as opposed to plucking them, gave performers a heightened possibility of playing loud or soft. This attractive possibility helped the pianoforte (or fortepiano—the terms are interchangeable) become the predominant keyboard instrument by the latter part of the eighteenth century.

Stephen Alltop at the piano |

Fortepiano |

Duetto

(Click here to see a larger version.)

In Emma, Frank Churchill buys for Jane Fairfax “a very elegant looking instrument—not a grand, but a large-sized square pianoforté . . . from Broadwood’s” (232). But just as it is not uncommon today to see a Steinway, Mason and Hamlin, or Chickering piano from one hundred years ago, there would have been plenty of older harpsichords and spinets still in homes during Jane Austen’s lifetime. The fact that harpsichords still existed at this time is made evident by the many publications that mention both instruments as mediums for the music therein. Many of the Austen family music volumes have “for harpsichord or pianoforte” written on the title pages.

Jane Austen was an amateur in the best sense of the word: she loved music, and it was an essential part of her daily life. Perhaps the best picture of Jane’s musical activities comes from her niece Caroline (born 1805), who wrote the following in 1867:

Aunt Jane began her day with music—for which I conclude she had a natural taste; as she thus kept it up—tho’ she had no one to teach; was never induced (as I have heard) to play in company; and none of her family cared much for it. I suppose, that she might not trouble them, she chose her practising time before breakfast—when she could have the room to herself—She practised regularly every morning—She played very pretty tunes, I thought—and I liked to stand by her and listen to them; but the music, (for I knew the books well in after years) would now be thought disgracefully easy—Much that she played from was manuscript, copied out by herself—and so neatly and correctly, that it was as easy to read as print—

At 9 o’ clock she made breakfast—that was her part of the household work. (170–71)

The years in Chawton (1809–1817) were highly productive for Jane Austen. Since she knew she would have the time before the 9:00 a.m. breakfast to herself, one could easily imagine that she would have coveted these quiet hours for her writing. But it would seem that she did not use the early morning for writing: she played the piano. We have no reports of Schubert or Beethoven, for instance, using the first hour of each day to work on their creative writing before setting about their composing in the afternoon. But music works on the mind in interesting ways, and I do wonder what creative gestations may have occurred as she communed with some of the music that she played.

![]()

At the time of her death, Jane left eight carefully assembled and bound volumes of music and two unbound collections. In all, the family had about eighteen music books dating back to the 1750s, two of which were rediscovered as recently as 2009.1 Given the loose hold artists had over intellectual property in those times, many recognizable themes are not attributed to their actual composers. There is just one uncredited reference to J. S. Bach in a keyboard work that draws its first bars from Bach’s Partita No. 1 in B-flat. There are several pieces of Mozart’s in various arrangements, and just one piece by Haydn. Gluck’s most famous melody, “Che faro senza Euridice,” appears in a quartet arrangement.

|

|

| Austen Family Music Books Binder's volume of printed and manuscript songs and keyboard music, c.1790-c.1810 |

|

Susanna

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Perhaps the greatest composer making numerous appearances in Jane Austen’s music books would be George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), who lived in England for fifty years and whose music had been published a great deal during his lifetime. The printed eighteenth-century volumes in the family’s possession contain arias from Messiah, Judas Maccabaeus, Acis and Galatea, Theodora, and several operas. Jane copied out pieces such as the famous Allegro from the Water Music and the Organ Concerto in B-flat Major, Op. 4, No. 2. One aria from Susanna, “Chastity, Thou, Cherub Bright,” is copied out in Jane’s hand. At a time when marriages were often arranged more for financial gain than genuine affection, chastity remained one bastion over which women could still hold control and was still so during the early nineteenth century. Another very sublime aria from Theodora, “Angels, ever bright and fair,” is found in the Austen music books. Theodora, persecuted for her Christianity has been sentenced to a fate worse than death: life in a brothel. In this aria, she asks the angels to rescue her.

“Angels ever bright and fair” from Theodora, performed Josefien Stoppelenburg and Stephen Alltop

The second volume of Austen’s instrumental music contains keyboard sonatas by Pleyel, Clementi, and Kočvara (in England, Kotzwara). The third book contains sonatas by Sterkel and Schobert (not Schubert, but Johann Schobert). Schobert came from the generation before Mozart, but his music was still highly regarded. These were the composers in fashion in the 1790s when Jane undertook her study of piano and when her musical tastes were formed.2 Ignaz Pleyel was certainly of some musical importance. He had studied with Haydn and composed widely. Mozart, writing to his father in 1785, shared high praise for Pleyel: “’Twill be a happy thing for music if Pleyel is some day able to replace Haydn for us!” One can almost imagine strolling toward the Chawton home on a misty English morning and hearing the muted sounds of Jane’s fortepiano playing a charming sonata by Pleyel or Haydn.3

The Soldier’s Adieu

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Charles Dibdin (1745–1814) is one of the most frequently cited composers in Austen’s song books. Dibdin was sometimes referred to as the British Schubert, this having more to do with his prolific output as a song composer than any comparison in artistic quality. Many of Dibdin’s songs referred to soldiers, sailors, and nautical life. Jane Austen was proud of her two brothers in the Navy and favored songs about sailors in her collections. In one Dibdin song in her books, “The Soldier’s Adieu,” Jane crossed out the word “soldier” and wrote “sailor.” It is typical that these songs were often set to pithy, even inscrutable texts. Dibdin’s song “Moorings” is typical of the mood and wit of his output:

“I’ve heard,” cried out one, “that you tars tack and tack,

And at sea what strange hardships befall you;

But I don’t know what’s moorings.”—“What don’t you?” said Jack;

“Man your ear-tackle, then, and I’ll tell you;

Suppose you’d a daughter quite Beautiful grown,

And, in spite of her prayr’s and implorings,

Some scoundrel abus’d her and you’d knock him down,

Why, d’ye see, he’d be safe at his moorings.If wedlock’s your port, and your mate, true and kind,

In all weathers will stick to her duty,

A calm of contentment shall beam in your mind,

Safe moor’d in the haven of beauty:

But if some frisky skiff, crank at every joint,

That listens to vows and adorings,

Shape your course how you will, still you’ll make Cuckold’s Point,

To lay up like a beacon at moorings.A glutton’s safe moor’d, head and stern, by the gout;

A drunkard’s moor’d under the table;

In straws, drowning men will Hope’s anchor find out;

While a hair’s philosopher’s cable:

Thus mankind are a ship, life a boisterous main,

Of Fate’s billows where all hear the roarings,

Where for one calm of pleasure, we’ve ten storms of pain,

Till death brings us all to our moorings.”

“Moorings," performed by Josefien Stoppelenburg and Stephen Alltop

It is important to note that the subjects and somewhat bawdy spirit of so many of Dibdin’s songs favored by Jane were quite at odds with the attributes Dibdin himself recommended for young women of the time. In his 1808 primer on the musical training of young women, called The Musical Mentor, Dibdin suggested that songs about Innocence, Constancy, and the Reproach of Vanity were appropriate subject matter. Jane’s love of the “less than innocent” Dibdin songs shows a bit what she enjoyed at home. For the performance of another nautical song by Dibdin, “The Lass That Loves the Sailor,” the audience at the JASNA AGM in Chicago sang along with gusto on the refrain, just as would have been done at an evening salon in Hampshire!

“The Lass That Loves a Sailor,” performed by Josefien Stoppelenburg and Stephen Alltop

Stephen Storace (1762–1796) is another featured composer in Jane’s books. He was born in London to an English mother and an Italian father, who was a professional contra bass player. His father had Stephen educated in Naples, though Stephen spent much of his time skipping his lessons to pursue his interests in painting. Many of his scores were adorned with beautiful engravings that may very well have been done by Storace himself. His sister, Nancy Storace, was a famous opera singer, who not only appeared in her brother’s works but also sang Susanna in Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro. When she departed Vienna, Mozart wrote the incomparable concert aria for soprano and solo piano “Chio mi scordi di te” for a concert to benefit Nancy Storace. While Stephen lived a brief life, he composed some very nice music and is particularly notable for lovely melodies, like this delightful aria, “How Mistaken Is the Lover,” from one of his most successful works, The Doctor and the Apothecary.

“How Mistaken Is the Lover,” performed by Josefien Stoppelenburg and Stephen Alltop

Of all Austen’s novels, Emma probably contains the most musical references. The only actual piece Jane ever refers to in her novels, the charming Irish folksong “Robin Adair” (262) is played by Jane Fairfax.4

Robin Adair

“Robin Adair”, performed by Josefien Stoppelenburg and Stephen Alltop

Jane Austen’s piano volumes included a set of variations on “Robin Adair” for piano by George Kiallmark (1781–1835).

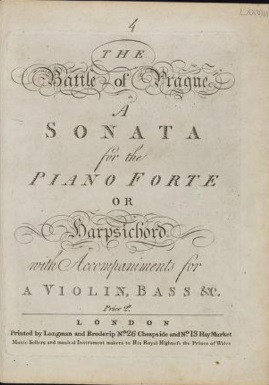

One of the pieces earmarked by either Jane or her teacher for special significance was František Kočvara’s The Battle of Prague. My friends, this may be one of the least profound pieces of music ever composed, but it surely was never meant to be more than it is—a splashy and humorously graphic portrayal of warfare to be enjoyed in the comfort and safety of the drawing room or parlor.

Battle of Prague

Excerpt from The Battle of Prague, performed by Josefien Stoppelenburg and Stephen Alltop

This short excursion has touched upon a mere sampling of the music Jane Austen enjoyed as an amateur pianist. The emotions these pieces conjure in us are surely similar to those felt by Jane and her listeners. From the sublime beauty of Handel’s arias to the whimsy of Dibdin’s confections, the ineffable ability of music to transcend time allows us to briefly stand unnoticed in the drawing room at Chawton, listening with pleasure to sounds from across the ages.

NOTES

1Complete Austen Family Music Books is available at https://archive.org/details/austenfamilymusicbooks.

2For an in-depth look at the music from Jane Austen’s youth, see Dooley.

3Pleyel became better known for his piano manufacturing business than his compositions.

4See Cawelti for a listing of the versions of “Robin Adair” reviewed in Ackermann’s Repository of the Arts between 1812 and 1816.