The question of Jane Austen’s source of inspiration for Longbourn and Meryton in Pride and Prejudice has frequently exercised the minds of Austen scholars and readers. Throughout the novel she scatters numerous clues to their location, tantalizing in their detail and suggestive of real places yet never allowing casual readers easily to work out for themselves which places she had in mind; there appears to be no straightforward, definitive answer. And yet, as we shall see, it is possible to identify Meryton, to make in-roads into identifying Longbourn, and in the process to shine a light on a source of inspiration for the geographies of Austen’s novels.

Since I first read Pride and Prejudice some thirty years ago, I felt that it should be practicable to work out the location of both places and sporadically pored over maps old and new in vain attempts to solve the problem. Then I came across Kenneth Smith’s essay “The Probable Location of Longbourn in Pride and Prejudice.” Using a systematic process of triangulating distances from London, Smith places Longbourn in the vicinity of Harpenden in Hertfordshire. Although not entirely convinced by his argument, I found his methodical and logical approach admirable and was inspired to try again.

But did Austen even have real locations in mind for Meryton and Longbourn? The accumulated evidence of the novel suggests she did, and the most suggestive indication is her anonymizing of the nearby town of “______.” If she had not wished to disguise heavily its location, she might have written “W______” (or some other initial consonant followed by a dash) as she does in The Watsons, for example, where “D______” is given for Dorking. The anonymity of “______” suggests that it is a real town, the identification of which would enable the reader to recognize Meryton and thence Longbourn, which Austen wanted to disguise, possibly because the novel makes reference to real events or people.

The key to identifying Meryton lies in Elizabeth Bennet’s journey to Kent, which she begins by travelling to her aunt and uncle’s house in Gracechurch Street, London, a distance given as twenty-four miles (PP 172). She travels with Sir William Lucas and his daughter in their private carriage; it is not stated whether they depart from Longbourn or Lucas Lodge, but the Bennets and the Lucases are close neighbors so it will make little practical difference: we may assume they live not more than half a mile apart as their houses are within “a short walk” of each other (19), and both are one mile from Meryton.

For me, the most telling (and inspiring) passage in Smith’s essay is found near the end:

It may well be the case that when Austen said the journey from Longbourn to Gracechurch Street was a journey of only twenty-four miles, she meant the journey by road rather than as the crow files. We obviously do not know the source of Austen’s claim that Longbourn/Lucas Lodge were exactly twenty-four miles from Gracechurch Street. (240–41).

Smith is I believe absolutely correct when he reflects that Austen may have meant the distance by road, but I disagree that we cannot know her source. As he notes, the precision of the measurement is typical of Austen and is probably significant, otherwise she could have written something vaguer, such as “a journey of nearly twenty-five miles.” When Austen says twenty-four miles, surely she means just that: no more, no less. Measure this distance via likely routes, and we should end up with a shortlist of candidates for Longbourn.

Unfortunately, this is not a simple process. We do not know the route Elizabeth is presumed to take, although it is certain she would travel along a main turnpike road. Nor do we know whether Longbourn is reached before Meryton, after it, or if it lies on a side road. And we must ask how a road is actually measured. As it turns out, however, none of these considerations much matters because it is possible to work out a distinctly limited range of distances within which Meryton must be situated and from there to examine all the candidate towns within that range.

It seems unlikely that Austen was stepping off distances on maps with a pair of dividers or counting milestones from the windows of coaches, and, in any case, she is not known with certainty to have visited Hertfordshire. She must have had a reliable source of geographical information on which to base her settings. This source could have been a family connection: her father’s second cousin the Rev. Thomas Bathurst was rector of Welwyn1 in Hertfordshire until his death in 1797, and Austen may have been able to ascertain local details from him (Le Faye 179; Jarvis 81).

More likely, though, Austen had access to a convenient, readily available, and accurate source of topographical information, which I believe was a travel itinerary. Itineraries were early travel guides that gave details of all the principal coaching routes throughout Great Britain. There were two popular publications of the time, Paterson’s Roads and Cary’s New Itinerary. Using a copy of either, Austen could have calculated the distance from Longbourn to Gracechurch Street.

Paterson’s Roads2 was first published in 1771 and went through eighteen editions by 1829. It is a mine of information: routes are broken down into stages by settlements and other significant places such as posting inns; each stage is given in statute miles and furlongs, along with the cumulative mileage from the starting point; textual markers indicate whether a town has a market, if it is a borough, and where roads pass into different counties. There are commentaries on towns and places of interest along the road such as the houses of notable people. Cary’s New Itinerary3 is similar but organized somewhat differently; it was first published in 1798 and went through eleven editions by 1828. It tends to be inferior to Paterson in quality of design but contains much the same information.

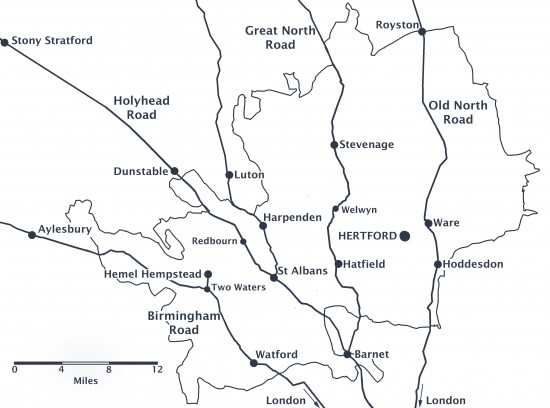

While they are one of Austen’s possible sources, neither itinerary directly solves the problem, as Hertfordshire lies to the north of London and is crossed by all four main roads to the north and northwest. Starting in the east, these are the Old North Road via Ware and Huntingdon to Alconbury Hill and so to the North; next is the Great North Road via Barnet, Hatfield, and Welwyn, joining the Old North Road at Alconbury Hill; farther west, the Holyhead Road branches from the Great North Road at Barnet to run via St Albans and Harpenden; westernmost is the Birmingham Road via Watford, Aylesbury, and Banbury.

Map of Hertfordshire showing roads and places mentioned in the text.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Distances were measured from the “standards” or datum points of each road. The standard for the Old North Road was Shoreditch Church, while the Great North and Holyhead Roads were measured from the site of Hick’s Hall in Clerkenwell; both are about one mile from Gracechurch Street. The Birmingham Road was measured from Tyburn turnpike gate, about three-and-a-half miles from Gracechurch Street. The first edition of Cary measured distances from a single datum, the General Post Office in Lombard Street, but this practice evidently caused confusion and from the second edition (1802) roads were measured from the commonly accepted standards, bringing mileages more into line with Paterson.

From all this information we can already deduce a surprising amount. If Elizabeth takes the Old North, Great North, or Holyhead Roads, her journey will be measured from one of two standards, each one mile from Gracechurch Street. Therefore, if Meryton is reached first when travelling from London, it must be twenty-two miles from the standard (twenty-three miles from Gracechurch Street), since Longbourn will be one mile farther on, to make a total journey of twenty-four miles. If Longbourn lies not directly on the route from London but to one side, the same principle applies. If, however, Longbourn is reached first, then Meryton must be another mile farther on at twenty-five miles from Gracechurch Street and therefore twenty-four miles from the standard. So Meryton must lie between twenty-two and twenty-four miles from the standard for either road. In the case of the Birmingham Road, it must lie between nineteen-and-a-half and twenty-one-and-a-half miles from Tyburn turnpike gate.

What else do we know about Meryton? It is a small market town with a mayor, formerly Sir William Lucas (19), and is therefore a borough—a town governed by an elected corporation. It has an Assembly Room (10) where the monthly ball is held (243). It cannot be far from the town of “______” because Mr. Bennet sends his two youngest daughters there unaccompanied by anyone other than (presumably) the coachman to meet Elizabeth on her return from Kent (242). We can deduce one further thing about Meryton, which is that it does not lie on a main coaching road. Austen does not specify how Elizabeth travels back from London, but, since she has to be met with a carriage, she must have travelled by public coach and has to be collected from the nearest town. We can infer, therefore, that “______” lies on a main coaching route and that Meryton must be some little distance off it.

So, to identify Meryton we are looking for a town in Hertfordshire that is a borough with a market and Assembly Room, that is within a prescribed distance from London, that is not on a main coaching route, and that has a neighboring town nearby that can be identified as “______.” Moreover, the distance has to be easily calculated using Paterson or Cary.

On the Birmingham Road there is no candidate within the required distance from Tyburn turnpike gate. Paterson lists Kings Langley at nineteen and three-quarter miles and Two Waters at twenty-two miles, but neither place is of any significance; Hemel Hempstead is twenty-three and a half miles via a side road from Two Waters, about twenty-seven miles from Gracechurch Street: too far, even if Longbourn is reached first (145).

Moving east to the Holyhead Road, St. Albans is a borough and has a market and an Assembly Room. It is twenty-one miles from London, only just outside the range we are looking for, but St. Albans is actually a small city with a large cathedral, which Austen surely would at least have hinted at if she had St. Albans in mind. It lies directly on the Holyhead Road, a further disqualifier. Farther along the same road, the village of Redbourn is Smith’s favored candidate for Longbourn, with Harpenden as Meryton. Despite the intriguing assonance of name, at twenty-five and a half miles from Hick’s Hall, Redbourn is too far from Gracechurch Street to be Longbourn while Harpenden, twenty-seven miles from the standard, is too far to be Meryton. In any case, both places lie on the main road.

Taking next the Great North Road, Hatfield is a market town but is not a borough and, at nineteen and a half miles from Hick’s Hall, is not nearly far enough. Welwyn, the living of Austen’s relation the Rev. Bathurst, at twenty-five miles is too far, is not a borough, and does not have a market. Again, both places are disqualified by lying directly on a main coaching road.

Farthest east, Ware on the Old North Road has often been suggested as the most likely candidate. It has a market but is not a borough and is only twenty and a half miles from Shoreditch Church. Moreover, it too lies on a main coaching route.

Only one candidate remains: Hertford,4 the county town of Hertfordshire. A small market town, in 1801 it had a population of 3,360. It is a borough (indicated by a dagger in Paterson, a superscript ‘b’ in Cary). Its Shire Hall (built 1771) survives, now used as a county court, and retains its Assembly Room. Most importantly, Hertford is not on a main road, lying as it does between the Old and Great North Roads. What of its distance from London?

Hertford Shire Hall.

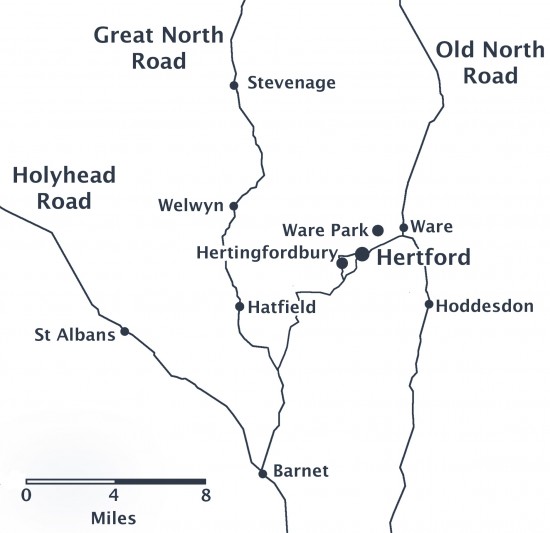

Paterson records a direct coach from London to Stevenage travelling via Hertford at a measured twenty-one miles from Shoreditch Church: not quite far enough (249). However, both Cary (444) and Paterson (248) give an alternative route via the Old North Road, nineteen and a quarter miles from Shoreditch Church to Amwell and a side road of two and three quarter miles to Hertford, making the distance twenty two miles exactly: within the range we are looking for. Add a mile from Gracechurch Street to Shoreditch Church and another mile from Hertford to Longbourn, and we have our distance of twenty-four miles from Longbourn to Gracechurch Street. Paterson also lists an alternative: the London to Carlisle route following the Great North Road through Barnet to a mile beyond Little Heath Lane, sixteen miles from Hick’s Hall, where a side road to Hertford for a further eight miles gives a total distance of twenty-four miles (178). An extra mile must be added for Hick’s Hall to Gracechurch Street, but if Longbourn were reached one mile before Hertford, then the journey would be twenty-four miles exactly.

Detail Map of Hertford area.

Austen provides corroborative evidence. Jane Bennet says that Lydia’s and Wickham’s presumed flight to Gretna Green has brought them “‘within ten miles of us’” (302). Gretna could be reached either by the Great North Road or by the Manchester Road, which branched from the Holyhead Road at Stony Stratford; Jane’s statement implies that Longbourn must be just about ten miles from the more distant of the two alternatives since if it was, say, only eight miles distant she would have specified that far instead. A radius of ten miles from Hertford just encompasses both roads to Gretna, but the equivalent location on the Birmingham Road (in the vicinity of Hemel Hempstead) is more than ten miles from the farthest route, the Great North Road. And it is the Great North Road that Colonel Forster takes when he enquires after the eloping couple “‘at all the turnpikes, and at the inns in Barnet and Hatfield.’” Furthermore, after his inquiries he “‘came on to Longbourn’” (303), indicating that it must be somewhere beyond Hatfield and in the environs of the Great North or Old North Roads; to continue to the Birmingham Road would be a circuitous route indeed.

Incidentally, locating Elizabeth’s aunt and uncle’s home at Gracechurch Street may not be coincidental, for Austen could have known it herself: Cary lists stage coaches leaving from inns there for Kent, which she could have used on her frequent trips to see her brother Edward at Godmersham Park. Another point of note is that Gracechurch Street is the continuation of the Old North Road as it enters the City of London, so her choice of that street could even have suggested the locations of Longbourn and Meryton, simply by following the road northwards.

Hertford is the only town that fits the profile of Meryton. And if Hertford is Meryton then the town of “______” must be Ware, only four miles away: an easy distance to send the two youngest daughters in the family coach. It cannot be Hatfield, the only other alternative, since that is mentioned specifically by name in the novel.

I am not, of course, the first person to come to this conclusion. Deirdre Le Faye states that towards the end of Pride and Prejudice “Longbourn is specified as lying within ten miles of the Great North Road” (179). In fact, Austen makes no such explicit declaration: Le Faye was probably thinking of Colonel Forster’s route and may have been unaware of the existence of the western road to Gretna. She continues, “This means that Jane could have mentally placed Meryton and the town of (Blank) somewhere in the area of either Hemel Hempstead and Watford to the west of the main road, or else Hertford and Ware to the east—and it can be deduced later on that Meryton is, in fact, Hertford and (Blank) is Ware” (179). But she does not explain how one is supposed to make this deduction from the text. Pat Rogers, in his notes to the Cambridge University Press edition, suggests either Ware or Hertford, though “Ware is slightly more likely” because of its location on the Old North Road, “a primary route for centuries” (PP 510n1). I have shown, I hope conclusively, that Le Faye was correct in her assumption. Furthermore, this deduction corroborates the identification of the “_____shire” Militia as the Derbyshire Militia, which was stationed at Hertford and Ware in 1794–1795 (Breihan and Caplan 24).

If we are confident in our identification of Meryton, then we are within reach of the possibility of identifying Longbourn. But here, alas, we are unable to be quite so conclusive.

What do we know about Longbourn? It is a village close to Meryton, the home of the Bennets and the Lucases, who are neighbors. Sir William Lucas has moved from Meryton to what is clearly a pre-existing dwelling, as Austen refers to it as “denominated from that period Lucas Lodge” (19); the appellation “lodge” suggests that it is not an especially large house, although clearly more than a lodge house at the gates to a bigger park. The residence of the Bennets is similarly one mile from Meryton (31) and is a substantial house, containing a vestibule, drawing room, dining parlor, and breakfast room, with grounds containing a lawn, shrubbery, a “little copse,” a “hermitage,” paddock, and parkland with “walks.” Mr. Bennet’s estate includes a farm, though clearly not a large one as his carriage horses are one and the same as the farm horses (34). Is there any place within a mile of Hertford which fits this description?

Hertingfordbury is a village one mile west of Hertford on the Hatfield Road. It contains a seventeenth-century house known as “Epcombs,” which was allegedly stayed in by Jane Austen and has been suggested as the model for Longbourn, but I have been unable to verify the evidence for this statement. Epcombs has relatively small grounds with no copse or hermitage and certainly no farm: a document in Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies records only the “House, Yard, Garden and two Meadows” (Pallett).

Epcombs.

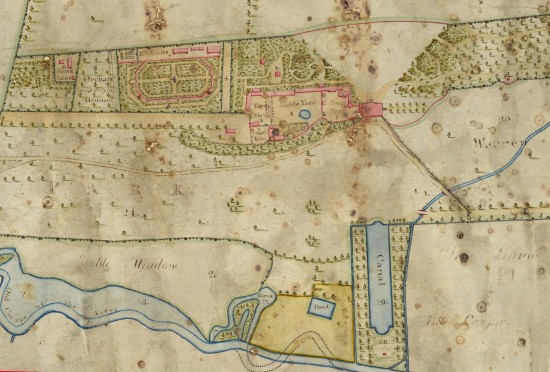

Nearby Hertingfordbury Park is of rather more interest. It is more than a mile from Hertford along the Hatfield Road but has a private drive that is exactly a mile to the town center via a different route. The distance from Hertingfordbury Park to Gracechurch Street would be twenty-four miles via either Ware or Hatfield. It has extensive grounds: an estate plan of 1773 indicates the presence of a lawn in front of the house, a park, formal garden and hot houses, as well as a farmyard and a stack yard (hay yard).5 There is, however, no trace of a hermitage; instead, the chief landscape feature here is a short canal across the park from the house leading south towards the river, in an area planted with trees in a regular pattern—reminiscent of an earlier, more formal style of garden.

Plan and Map of Hertingfordbury, by John Waddington (1773). Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies, D/EP.P12.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

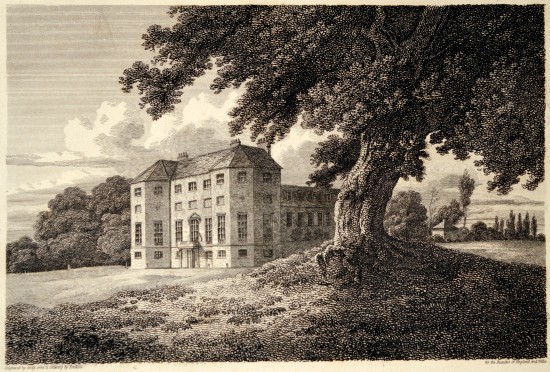

View of Hertingfordbury Park (ca. 1785–1805). Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies (HALS), DE/Of/3/488.

Hertingfordbury Park at the end of the eighteenth century was in the ownership of Earl Cowper and appears to have been rather grander than Austen’s description of Longbourn House (and the Bennet’s lifestyle) suggests. Nevertheless, it is a strong candidate, in which case Epcombs is a clear contender for Lucas Lodge, the two properties being less than half a mile apart and situated such that it would be easy for the Bennets to call on the Lucases on their way back from Meryton/Hertford.

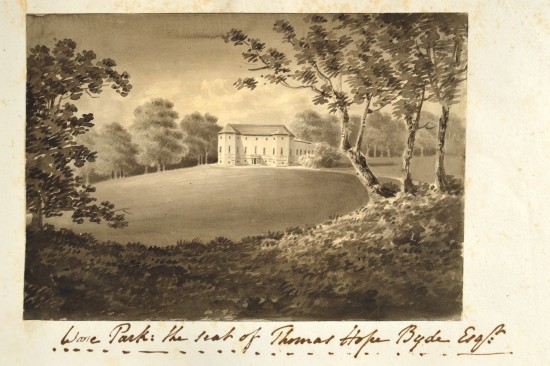

There is, however, another candidate. Ware Park to the northeast of Hertford was a sizeable house with grounds containing a lawn, copse, and farm, and Historic England records attest the existence of a hermitage. The property was sold by auction in 1826, and the sale particulars and map describe the land in eloquent terms: “A capital mansion, of regular distinguished appearance, planned with noble suits of apartments seated in a beautiful park . . . , calculated for a family of the first consideration and fortune, the walks are various and pleasant . . . , the grounds enriched with thriving shrubberies and plantations.”6

Ware Park—the seat of Thomas Hope Byde Esquire [watercolor, early 19th century]. Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies, CV/WAR/42

Ware Park, Hertfordshire (1 Mar. 1812). Engraved by John Greig after Charles Tomkins for The Beauties of England and Wales. Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies, Hine/123b/75.

The description of the house with its vestibule, drawing room, dining parlor, and library bears similarities to Longbourn, but, like Hertingfordbury, Ware Park is grander than the image Austen projects: there is a “Justice Room,” no less than ten principal bedrooms, two butler’s pantries, kitchen gardens with a “Melon Ground,” four double coach-houses with stabling for twenty-eight horses, and a farm stable for seven horses—a far cry from Mr. Bennet’s coach-cum-farm horses. It should be added that Ware Park is somewhat more than a mile from the town (but perhaps Austen was not so precise about such short distances), and there is no nearby house that would fit the description of Lucas Lodge.

For the present, I cannot conclude that either house alone is Longbourn. I am inclined to believe that Longbourn is set in the location of Hertingfordbury Park but that is not a portrait of a single place and is more likely a composite of some of the features of both mansions—perhaps other houses too—and more modest in scale. If that is the case, then it opens up the intriguing possibility that Jane Austen may have visited Hertford after all since her setting matches local geography so well in numerous small details that would be difficult to acquire remotely.

Curiously, Hertingfordbury church has a monument that reinforces the Derbyshire connection. The monument is dedicated to Sir Christopher Vernon, Lord of Hertingfordbury Manor (died 1652), who originated from Haddon Hall in Derbyshire. Readers may recall that Vernon is the familial name of the eponymous heroine of Austen’s juvenile novel Lady Susan and that Haddon Hall is close to Chatsworth, one of the sights on Elizabeth Bennet’s northern tour. This may well be a coincidence, but it is a striking one nonetheless: if Jane Austen did stay at or visit Epcombs, she might well have taken notice of this monument.

There remains the question of which itinerary Austen might have used, Cary or Paterson? She could of course have had access to both: they were very popular books, which ran into numerous editions each, and there was little to choose between them. But there is a clue to which is likely to have been her main source. In Emma, Mr. Woodhouse advises his daughter Isabella on the Knightley family’s trip to the sea:

“You should have gone to Cromer, my dear, if you went any where.—Perry was a week at Cromer once, and he holds it to be the best of all the sea-bathing places. A fine open sea, he says, and very pure air.”’ (113)

Isabella replies that Cromer would mean a journey of “‘[a] hundred miles, perhaps,’” a very inadequate guess but one most appropriate to Isabella’s character, who cannot be expected to take much interest in the details of journeys. Her husband can, however, and replies, “‘If Mr. Perry can tell me how to convey a wife and five children a distance of an hundred and thirty miles with no greater expense or inconvenience than a distance of forty, I should be as willing to prefer Cromer to South End as much as himself’” (114). Paterson’s Roads lists three different routes from London to Cromer, one of which is 130 miles exactly, and notes that the town “has a fine beach for bathing” (262–64).

Finally, what of that name “Meryton”? There is no such place name in Britain, but there are five examples of “Cheriton.” One of these is near Folkestone, not many miles from Edward Knight’s home at Godmersham. The other is in Hampshire, less than ten miles from Chawton. Interestingly, about one mile away is the village of Tichborne.7 Another coincidence? Perhaps, but maybe Jane Austen, at Chawton when revising Pride and Prejudice for publication, was tempted to look around her locally for inspiration for names, if not actual places.

NOTES

2Properly, A New and Accurate Description of all the Direct and Principal Cross Roads in Great Britain, containing: i. An Alphabetical List of all the Cities, Boroughs, Market and Sea-port Towns in England and Wales; ii. The Direct Roads from London to all the Cities, Towns, and Remarkable Villages in England and Wales; iii. The Cross Roads of England and Wales; iv. The Principal Direct and Cross Roads of Scotland; v. The Circuits of the Judges.

3In full, Cary’s New Itinerary: or An Accurate Delineation of the Great Roads, Both Direct and Cross, Throughout England and Wales; With Many of the Principal Roads in Scotland. From an Actual Admeasurement by John Cary; Made by Command of His Majesty’s Postmaster General, for Official Purposes: Under the Direction and Inspection of Thomas Hasker Esqr. Surveyor and Superintendant of the Mail Coaches.

4The correct pronunciation is “Harford” (hence the county should be pronounced “Harfordshire”) although nowadays the “t” is more usually pronounced.

5This house, which from descriptions appears to have dated from the late seventeenth century, burned down in 1816.

6See Sale Particulars of Ware Park. The mansion described in the 1826 sale particulars burned down in 1865, and the present house was erected in its place.

7Later in the nineteenth century Tichborne became infamous for the bizarre case of the Tichborne Claimant that so scandalized mid-Victorian society, in which an obscure and impecunious Australian butcher claimed to be the missing son of Lady Tichborne and heir to the Tichborne estates.