Mansfield Park has long been regarded as Austen’s darkest, most challenging, most moralistic, and most overtly didactic novel, and, as such, it is arguably Austen’s least “beloved” work. Julia Prewitt Brown, for example, describes Mansfield Park as an “ambitious” novel, but feels that it “does not delight; its vehemence moves us to silence” (80). The case for Mansfield Park as a reactionary didactic novel reached its apotheosis in Marilyn Butler’s seminal and still influential work Jane Austen and the War of Ideas. For Butler, Mansfield Park is “the most visibly ideological of Austen’s novels” (219). It is, Butler goes on to note, clear in its authorial purpose: it is “a book which says what Jane Austen meant it to say” (245). For all its brilliance, this apparently stringent moral didacticism seems to negate the playfulness, gaiety, and even the (relative) liberality of its predecessor, Pride and Prejudice.

Perhaps Mansfield Park suffers for the unhappy accident of the chronology of its creation, but it is undoubtedly the most controversial of her novels and a critical shibboleth.1 The critical debate surrounding Mansfield Park has been for some time somewhat overshadowed by historicist critics’ intense focus on Austen’s supposed admiration for the Evangelical religious movement.2 The source of speculation on Austen’s putative “conversion” to Evangelicalism is found in her letters. To Martha Lloyd in 1814, Austen wrote that England was a nation “improving in Religion” (2 September 1814). In the same year, in response to her niece Fanny’s qualms over her suitor’s Evangelicalism, Austen wrote, “I am by no means convinced that we ought not all to be Evangelicals” (18–20 November 1814). These brief comments have served for some critics as incontrovertible evidence of Austen’s personal support for the movement.3 Such support, if genuine, signaled a volte face from an earlier position demonstrated in a much earlier letter to her sister, Cassandra Austen, in which she declared, “I do not like the Evangelicals” (24 January 1809).

Regardless of the reliability of the “evidence” drawn from her correspondence, such intense focus on one narrow, biographically determined aspect of historical context has led to the underplaying of the aesthetic complexity of the text, resulting in binary, reductionist readings of Mansfield Park. While maintaining the importance of historical contexts, a greater focus on the novel’s form helps demonstrate how critical responses that regard it primarily as a didactic novel greatly underestimate its narrative and stylistic complexity as a polyvocal response to—rather than monologic endorsement or rejection of—its Evangelical influences.

Identifying the differing approaches to narrative authority in Mansfield Park and Evangelical fiction and the latter’s influence on the formation of moral judgement offers a way to re-examine the true impact of Evangelical fiction on Austen’s novel. To do this, I will look closely at the novel’s central relationship between Fanny and her mentor, Edmund Bertram, focusing particularly on the first part of volume 1 of the novel. If Mansfield Park’s moral impetus is straightforwardly didactic, then that relationship would be an unproblematic version of similar relationships between ingénues and their mentor-lovers, common in a great deal of popular fiction. If, however, Mansfield Park asks the reader to engage more critically with narrative authority, the relationship is rendered deeply problematic, particularly in terms of the novel’s putative ultra-conservatism. By demonstrating the ways in which the narrative dismantles the apparent solidity of its central relationship, we can see how Mansfield Park questions narrative authority and—by extension—the social conservatism it appears to endorse.

The most immediately obvious starting point for such an examination has previously been the theatricals, when the Bertrams and the Crawfords attempt to stage an amateur production of Lovers’ Vows by Kotzebue. The importance of this episode to the novel as a whole cannot be underestimated. Furthermore, the text’s ambiguous handling of the episode has meant that persuasive arguments claiming the theatricals as evidence for Austen’s conservatism have been evenly matched by those that claim them as evidence for her radicalism.4 Irrespective of a perceived expression of political allegiance, for many critics, the theatricals are so structurally brilliant and thematically integral to the novel’s development that they seem to cast the rest of the first volume of the novel into shadow. As a result, that the earlier chapters remain relatively under-examined for its contribution to the debate surrounding the novel’s moral authority.

The theatricals certainly do highlight an apparent hiatus in the relationship between Edmund and Fanny, which, up until this point, is seemingly a straightforward one between a kind, sensible, and morally unimpeachable mentor and his adoring pupil. As the participants struggle to fill the roles, an initially reluctant Edmund finds himself offering to play the part of Anhalt, the lover of Amelia, played by Mary Crawford. His decision sparks great concern in Fanny, who is shocked by what is apparently Edmund’s first moral infraction: “Could it be possible?” she wonders, “Edmund so inconsistent” (183). Edmund has apparently “descended from that moral elevation which he had maintained before” (185), and Fanny is shocked by his uncharacteristic errors of judgment. The realization has repercussions for the rest of the narrative as Fanny’s persistent moral rectitude forces her further into isolation at Mansfield and further away from Edmund’s notice.

Far from offering an unforeseen turning-point in their relationship, however, this episode is in fact an inevitable outcome of a relationship that has been problematic from the very beginning. In fact, the very words that signal Fanny’s surprise at Edmund’s poor judgment contain within them a hint that his judgment never has been infallible. Looking again, we notice that “Edmund so inconsistent” is a statement rather than a question, or even an exclamation. When we also consider focalization, we begin to see that the issue of who is passing judgment on Edmund’s lack of judgment is muddied: is this assessment filtered through Fanny, or is it a narrative judgment? Either way, it throws into relief two interesting ideas—that Edmund is not and never has been perfect, and that the more formal aspects of Austen’s style have a crucial role to play in any examination of Austen’s putative didacticism. Consequently, not only ought criticism to acknowledge Austen’s engagement with her literary peers and predecessors, but it must also turn its attention to the formal aspects of Austen’s style that have, until recently, remained curiously under-examined. In the introduction to The Language of Jane Austen, Joe Bray acknowledges that there remains a lack of critical attention to “what exactly makes Austen’s language and style susceptible to such continuing diverse re-interpretation” (2–3).

Austen’s stylistic complexity and the influence of Evangelical fiction

A critical analysis of “what exactly” makes Austen’s novels stylistically important chimes well with John Wiltshire’s assertion that her work requires the same kind of close reading that is demanded of poetry (5). Austen’s style is notoriously difficult to pin down, but, as Bray in particular demonstrates, although it might be challenging formally to analyze Austen’s stylistic devices, it is not impossible.5 In the very recently published Jane Austen’s Style, Anne Toner also reconsiders Austen’s style by focusing on a number of specific rhetorical devices that recur throughout Austen’s work. Furthermore, if we examine closely the minutiae of the novel’s form and narrative structure, we can begin to appreciate that Mansfield Park’s engagement with Evangelical contexts reveals itself as a primarily literary and aesthetic engagement rather than an ideological one. In such a critical context, whether Austen herself was Evangelical, radical, or conservative is almost irrelevant; what is relevant is the fact that all such ideas are interrogated in her work at all.6

A closer scrutiny of Mansfield Park’s stylistic complexity allows for a more nuanced understanding of the Evangelical novel. When examining the potential influence of Evangelicalism on Mansfield Park, criticism should also consider the latter’s interrogation of the relationships between the reader and the text and the author and the text, because both these relationships are crucial to the creation of more discerning, more independent, and more critically thinking readers. Evangelical fiction’s anxieties are centered in its discomfort with its own fictionality. Although Evangelical writers expressed few qualms about their own moral authority, they did have doubts about the novel as an appropriate medium for conveying their principles.

For all the clarity of their purpose, avowedly Evangelical writers like Mary Brunton and Hannah More expressed in very clear terms their distrust of the novel. Hannah More, for example, wrote that, “the corruption occasioned by these books has spread so wide, and descended so low . . . [that] among milliners, mantua-makers, and other trades where numbers work together, the labour of one girl is frequently sacrificed that she may be spared to read those mischievous books to the others” (186–87). For More and other Evangelical novelists such as Mary Brunton, however, the novel—despite its potential to distract and misguide its readers—contained within it the potential for its own reformation into a vehicle for didactic spiritual and religious guidance; like the wayward sinner, the novel was converted, and it in turn became a proselytizing voice. In “The Evangelical Novel,” Lisa Wood notes that the decision to use the novel as a didactic tool was a cunning one; by harnessing the popularity of the novel, religious instruction could be made appealing to a wider audience. Furthermore, the novel, with its frequent focus on the development or education of an individual, offered Evangelical doctrine a clear and linear narrative structure in which an individual might progress—in a relatively straightforward way—towards a state of grace (527).

The didactic potential of the novel was of much greater importance to Evangelical writers than any aesthetic purpose—as evidenced in Brunton’s advertisement to the second edition of Self-Control, in which she categorically prioritizes her novel’s moral function:

The commendations bestowed on Self-Control have been by no means unqualified. Strictures have been made up on various parts of the narrative, and objections stated against the probability of some of the incidents. Had these censures been pointed against the lessons which the tale was intended to convey, the Author would have felt it her duty, as well as her earnest desire to remove them. (4)

She goes on to note that changes have subsequently been made to the language, “either where the expression was faulty, or where it has been said to bear a meaning which it was not intended to convey” (4). Brunton makes clear that the message is more important to its author than the literary means through which it is conveyed. In Jane Austen and the Popular Novel, Anthony Mandal makes an interesting distinction between strictly Evangelical fiction of earlier writers such as Hannah More and writers of what he calls the “moral-domestic novel.” He includes Mary Brunton in the latter category. Mandal writes that, although the moral-domestic novel shares “similar concerns with its heroine’s spiritual and moral states,” there is also a “less categorical focus on religion . . . [and] more on appropriate codes of behavior within the domestic sphere” (95). I would maintain, however, that Evangelical fiction such as Brunton’s is never entirely at ease with its own fictionality and uses it only to direct its readers to better judgment.

Consequently, the reader’s engagement is never allowed to stretch to freedom of judgment—ideologically or narratively. There is, as Lisa Wood notes, an inevitability to the narrative and to the conclusion to which the reader is guided through the text’s reliance on, for instance, biblical references, homiletic interjections by the narrator, or narratives that are focalized through an older and wiser narrator who comments instructively on his or her previous errors (521–36). In Mansfield Park we can trace at least the first two of these characteristics. The novels, however, differ in intention: Mansfield Park seeks to create better—that is, more independent—readers, who are capable of reading behind the narrative’s surface gloss of certainty, whereas Evangelical fiction’s better readers show their improvement through the complete acceptance of the religious truths conveyed through the narrative.

In examining the potential influence of Evangelicalism on Mansfield Park, criticism should consider the novel’s engagement with the implications of the genre’s overt didacticism for the relationship between reader and text, and the author and text because this relationship is crucial to the development of the reader’s skills. Looking again at Brunton’s statement in the second edition about her duty as an author to remove aspects of the text that do not serve its main objective, we see an underlying assumption of ownership over the text. Brunton’s assertion in turn implies great unease at the idea that a reader might form his or her own ideas about the text’s message and meaning. Evangelical fiction endorses a monologic interpretation of its clearly stated intentions, and it assumes that the reader will accept narrative authority as absolute. This kind of homiletic monologism, however, is antithetical to a novel like Mansfield Park that is so interested in a text’s potential to convey a multiplicity, not so much of interpretations, but of conversations about the subjects and objects of its own discourses. Furthermore, a close reading of the text reveals that it does not always support its own apparent message. By continually destabilizing itself, the narrative invites the intelligent reader to treat narrative authority with a considerable degree of skepticism. In Jane Austen and her Readers, Katie Halsey describes the relationship between Austen and her readers as “a dynamic two-way process wherein readers respond to the novels but the novels and characters are also brought to life, re-imagined, re-created and re-invented in and through the reading experience in its totality” (3). This kind of interlocutory, almost democratic, relationship between narrator and reader is a radical departure from the Evangelical reliance on narrative authority as a means of easily conveying a clear (and usually conservative) message.

Re-evaluating the relationship between Edmund and Fanny

Edmund’s attempts to console Fanny when he finds her weeping alone on the stairs offers the first of the text’s efforts to undermine the messages it seems to endorse, and the actual unsuitability of Edmund’s role of mentor is revealed in his misunderstanding of Fanny’s feelings—something that will recur again and again throughout the novel. He divines that

“You are sorry to leave Mama, my dear little Fanny,” said he, “which shows you to be a very good girl; but you must remember that you are with relations and friends, who all love you, and wish to make you happy.” (17)

Edmund’s emotional short-sightedness is further compounded by his declaration that her relations love her. Like his father, Sir Thomas, Edmund relies on an idealized version of familial love and duty that does not exist at Mansfield. On her first arrival, her uncle intimidates her, Mrs. Norris immediately begins her ceaseless campaign of bullying, Tom and Edmund greet her with “much good humour” but little interest, while Maria and Julia scrutinize her appearance (13). Edmund’s obtuse inability to see how things really are will later be played out again in his determined failure to understand Fanny’s pain at the thought of living with Aunt Norris, his lack of self-awareness of his own motives for joining in the theatricals, and his misreading not only of Fanny’s character, but of Mary Crawford’s also. Edmund’s platitudes are expressed in sententious language that carries more than a hint of the sermon—language even a little reminiscent of that most comically dreadful of clergymen, Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice.

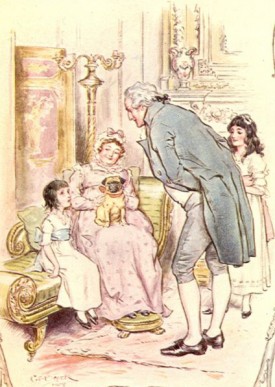

Edmund’s reassurances that Fanny is surrounded by people who love her are highly ironic. The reader chastises Edmund for his lack of insight into his cousin’s predicament; we see the evidence to the contrary that he does not see. If we pause and recollect whose point of view the evidence has actually been focalized through up until this point, we remember that it is mainly Fanny’s; she is a timid, retiring child of socially insignificant parents, who has been suddenly thrust into an alien world. Regardless of how welcoming the Bertrams are or are not, her bewildered and frightened response is possibly made more terrible by her own very normal fears and anxieties. Although the text emphasizes that their efforts were “in vain,” we are told that Sir Thomas “tried to be all that was conciliating.” Even Lady Bertram (for all her faults) attempts to encourage Fanny with her “good-humoured smile” (13). A little further on in the chapter, we are told that “in vain did Lady Bertram smile and make [Fanny] sit on the sofa with herself and pug, and vain even was the sight of a gooseberry tart towards giving her comfort” (15).

Edmund’s reassurances that Fanny is surrounded by people who love her are highly ironic. The reader chastises Edmund for his lack of insight into his cousin’s predicament; we see the evidence to the contrary that he does not see. If we pause and recollect whose point of view the evidence has actually been focalized through up until this point, we remember that it is mainly Fanny’s; she is a timid, retiring child of socially insignificant parents, who has been suddenly thrust into an alien world. Regardless of how welcoming the Bertrams are or are not, her bewildered and frightened response is possibly made more terrible by her own very normal fears and anxieties. Although the text emphasizes that their efforts were “in vain,” we are told that Sir Thomas “tried to be all that was conciliating.” Even Lady Bertram (for all her faults) attempts to encourage Fanny with her “good-humoured smile” (13). A little further on in the chapter, we are told that “in vain did Lady Bertram smile and make [Fanny] sit on the sofa with herself and pug, and vain even was the sight of a gooseberry tart towards giving her comfort” (15).

There is more than a hint that at least one person in the house is attempting to be nice to Fanny. One object in particular seems, however, to emblematize the text’s initial ambivalence over whether or not Fanny’s misery (although justified), is exacerbated by her own personality. That one object is the gooseberry tart.7 The repetition of the phrase “in vain” suggests that several small, though well-meaning efforts are being made by the Bertrams, the offer of the tart being one of them. The gooseberry tart could either uphold or undermine the legitimacy of Fanny’s fears. A gooseberry tart, although probably not exactly a luxury, would at the very least have been a seasonal treat—certainly one not readily available to the Price family in Portsmouth. It may be offered as an act of kindness that Fanny is yet too overwhelmed to see as such, but it could equally signify the abundance of the Bertrams’ table and therefore offer a stark and unpleasant contrast to the home she has left—another source of her feelings of alienation. The textual evidence seems largely to support Fanny’s point of view, but by dropping clues for the observant reader (such as the tart and Lady Bertram’s efforts), it refuses wholly to endorse its heroine in this particular instance. The suggestion that Fanny is too timid to appreciate the Bertams’ largesse is signaled again later in the text by the fact that her sister Susan relishes her transfer from Portsmouth to Mansfield.

The chapter ends with an apparent confirmation of the important role Edmund plays in Fanny’s education. He contributes greatly to

the improvement of her mind, and extending its pleasures. He knew her to be clever, to have a quick apprehension as well as good sense, and a fondness for reading, which, properly directed, must be an education in itself. . . . [H]e recommended the books which charmed her leisure hours, he encouraged her taste, and corrected her judgment, he made reading useful by talking to her of what she read, and heightened its attraction by judicious praise. In return for such services, she loved him better than anybody in the world except William; her heart was divided between the two. (24–25)

This précis of Edmund’s influence on Fanny bears a striking resemblance to that of Mrs. Douglas on the young Laura in Brunton’s Self-Control. The narrator of Brunton’s novel states that Mrs. Douglas was

of sound sense, rather than of brilliant abilities; reserved in her manners, gentle in her temper, pious, humble, and upright: she spent her life in the diligent and unostentatious discharge of Christian and feminine duty. . . . She always treated the little Laura with more than common kindness, and the child, unused to the fascinations of feminine kindness, repaid her attention with the utmost enthusiasm of love and veneration. With her she passed every moment allowed for her recreation; to her she applied in every little difficulty; from her she solicited every childish indulgence. The influence of this excellent woman increased with Laura’s age, till her approbation became essential to the peace of mind of her young friend, who instinctively sought to read, in the expressive countenance of Mrs. Douglas, an opinion of all her words and actions. Mrs. Douglas, ever watchful for the good of all who approached her, used every effort to render this attachment useful as it was delightful, and gradually laid the foundation of the most valuable qualities in the mind of Laura. (7)

The similarities between Laura and her relationship with Mrs. Douglas and Fanny and hers with Edmund are clear. Mrs. Douglas encourages young Laura in much the same way that Edmund encourages Fanny. The reader is told through non-focalized third-person narrative that Mrs. Douglas is a good person and an excellent moral guide. Her role in the development of Laura’s most “valuable qualities” is in no way questioned or undermined by the narrative.

The clear parallels between the extracts above from Mansfield Park and Self-Control do not extend to narrative manipulation. There is a clear echo between “he recommended . . . he encouraged . . . he made” and “With her . . . to her . . . from her.” The crucial difference lies in the fact that one narrator grants the pupil agency in the development of her taste, judgment, and character, while the other does not. Laura applies to Mrs. Douglas, seeks out her guidance, suggesting that she has inherent sense enough to want to learn from her mentor’s superior judgment. Nor does the narrative offer any reason to doubt that superiority. Ironically, the passage describes the ideal pupil-mentor relationship through a narrative method that does not extend the same privilege to its readers.

Edmund and Fanny at odds

In the passage from Mansfield Park, the third-person omniscient narration does not, on first reading, seem to offer an ironic gloss on this categorical statement of his role in Fanny’s education. If we re-read it on the understanding that, “He knew her to be clever” is an instance of reported thought, however, then what follows could potentially be read as focalized through Edmund.8 Fanny, his pupil, is silenced completely, and, because of this silencing, we question the narrative’s apparently objective assessment of Edmund’s help as being useful and his praise “judicious.” With the use of Edmund’s favorite modal verb, “must,” the narrative again suggests that we are actually seeing his point of view here. That “must” is immediately followed by a very brief account of Miss Lee’s role in Fanny’s education: to give her a smattering of French and History. If it is Edmund’s belief that reading constitutes “an education in itself,” then he must be aware of gaps left by Miss Lee that need to be plugged and that he feels an obligation to plug them. (Miss Lee’s competence has already been put in doubt when Maria and Julia sneer at Fanny’s lack of knowledge and reveal the paucity of what they have learned from her.) The statement that he “corrected her judgement” therefore becomes less obviously a statement of fact given by an objective omniscient narrator. In this way, the narrative plays not merely with the reader’s expectations of the relationship between Fanny and Edmund but also with the reliability of any third-person, supposedly objective narrative.

Mansfield Park may not be as lively and sparkling a novel as its predecessor, but there is a kind of grim, bleakly ironic humor in the novel’s artful dissection of the mentor-pupil relationship and its subtle exposure of the fact that its hero and heroine are so continually at odds. When Fanny fears that she may have to live with her Aunt Norris, for example, the two almost clash in their assessment of the plan:

“Cousin,” said she, “something is going to happen which I do not like at all; and though you have often persuaded me into being reconciled to things that I disliked at first, you will not be able to do it now. I am going to live entirely with my aunt Norris.”

. . .

“Well, Fanny, and if the plan were not unpleasant to you, I should call it an excellent one.”

“Oh! Cousin!”

“It has everything else in its favour. My aunt is acting like a sensible woman in wishing for you. She is choosing a friend and companion exactly where she ought, and I am glad her love of money does not interfere. You will be what you ought to be to her. I hope it does not distress you very much, Fanny.”

“Indeed it does. I cannot like it. I love this house and everything in it. I shall love nothing there. You know how uncomfortable I feel with her.”

“I can say nothing for her manner to you as a child; but it was the same with us all, or nearly so. She never knew how to be pleasant to children. But you are now of an age to be treated better; I think she is behaving better already; and when you are her only companion, you must be important to her.” (29)

The passage is noticeably lacking in speech attribution,9 and the narrator seems to have withdrawn completely from the text. The characters thereby have complete freedom to present themselves to the reader as they are, so to speak; the reader is equally free of narrative intervention. As Anne Toner points out, a similarly lengthy exchange takes place between Mr. and Mrs. Bennet in the opening of Pride and Prejudice, which “portrays the fractious intimacy of a long-married couple whose antagonism is best conveyed without mediation” (172). If we examine the dialogue between Fanny and Edmund very closely, we see that their relationship is, perhaps surprisingly, in many ways just as fractious as the Bennets’. Fanny acknowledges that although Edmund has often “‘persuaded me into being reconciled to things that I disliked at first, you will not be able to do it now’” (29). Fanny is often disliked by readers for her meekness, but this statement is decidedly assertive, and the certainty of “you will not” leaves no room for doubt, unlike the modality of Edmund’s “musts” and “oughts.” The lack of a reporting clause here is significant. The absence of a mediating narrative comment creates ambiguity that lends greater force to her declaration because it offers the possibility of a potentially subversive rebuttal of Edmund’s patriarchal, and therefore socially endorsed, superiority.

Edmund, of course, argues that the plan is an excellent one; yet even Mrs. Norris shows greater insight than Edmund when she tells Lady Bertram that it would be “‘the last thing in the world . . . for any body to wish that really knows us both’” (32). The absence of a reporting clause in Fanny’s exclamation, “‘Oh! Cousin!’” in response to his reassurances offers the reader more than one potential interpretation. Readers often complain that Fanny is too passive and consequently read such utterances as a sign of her acquiescence to Edmund’s superior wisdom. Yet those exclamation marks might just as likely express shocked resistance, or even gentle reproof, rather than disappointed and abject resignation to superior judgment. In fact, the rest of their interaction shows Fanny to be perfectly capable of disagreeing with Edmund. Edmund reassures her that “‘You will be what you ought to be to her’” (29); the combination here of the future perfect tense and the “ought” reflects Edmund’s persistently naïve view of how the world works: in an ideal world, a young girl ought to be loved by her aunt; Fanny clearly is not. Again, the lack of reporting clause or narrative comment renders his wish that “it does not distress you very much, Fanny” (29) highly ambiguous. Does he refer to his prediction, or to the news of her move? If it is about the latter, then it suggests that, yet again, Edmund is not properly listening to Fanny.

Fanny’s response to Edmund’s reassurances is very significant. She is adamant that the news does upset her and that she “‘cannot like it. I love this house and every thing in it. I shall love nothing there. You know how uncomfortable I feel with her’” (29). The reader may well react with skepticism to Fanny’s declaration that she loves everything about Mansfield because the evidence suggests that she does not. Nevertheless, her dislike of Mrs. Norris is more than legitimized by her experience. At first, in light of what Edmund says, her logic might seem as specious as Edmund’s—she is happy at Mansfield; therefore she cannot be happy with Mrs. Norris. Her pointed reminder to Edmund that he knows how much she dislikes her aunt, however, serves as the missing step in her logical leap and highlights the more serious flaw in his. Fanny reminds her mentor that the evidence more than implies the probability of her predicted unhappiness. Again, we see that the narrative stresses the importance of acquired female experience over abstract and male ideas of what ought to be. Furthermore, Fanny’s insistence on the importance of evidence in the formation of judgment suggests an allegiance to a posteriori knowledge that is at odds with the Evangelical reliance on one’s inner—and therefore a priori—sense of right and wrong. Negotiating the world is far more complex than Edmund would have Fanny believe because of the existence of self-centered people like Mrs. Norris who do not behave as good Christians ought to behave. Fanny understands this fact better than Edmund does.

Edmund’s a priori certainties cannot help but force him into modalities again and again: as her aunt’s only companion, she must be important; she should be loved because she is kind; she ought to be “brought forward” (30). Eventually Fanny seems to succumb to Edmund’s logic:

Fanny sighed, and said, “I cannot see things as you do; but I ought to believe you to be right rather than myself, and I am very much obliged to you for trying to reconcile me what must be. If I could suppose my aunt really to care for me, it would be delightful to feel myself of consequence to any body!—Here, I know I am of none, and yet I love the place so well. (30–31)

Closer examination, however, reveals that Fanny’s submission could be read as a forceful attempt at resistance. Notice how she echoes Edmund’s use of modal verbs, apparently signaling her acquiescence to Edmund’s naïve reassurances. The fact that she does not follow her suggestion of what “ought” to be with a confirmation in the future tense of the inevitability of Edmund’s surmising, however, is significant. In other words, for Fanny, this “ought” does not translate into what is or what will be. In knowing that she “ought” to believe him to be right, she signals an uncertainty that both echoes and negates the authority of his judgments; Fanny seems subtly to hint that she is in fact uncertain about Edmund’s assessment of the situation. In other words, she knows that Edmund is wrong. She maintains her belief that she “cannot” agree with him. Furthermore, Fanny rejects Edmund’s use of modality to reach her own conclusions about how the world really is. Fanny’s use of “if” is important because it re-implies the counterfactual statement that she “cannot” as a rebuttal of Edmund’s logic. It is also significant that her feelings are expressed in direct speech, unmediated by the narrative voice. Again, the reader is free to ascribe to Fanny the resistance that the narrative appears to deny her. At first the narrative seems to deny Fanny any power of resistance by placing her against an interlocutor whose social superiority ensures that she cannot overcome him. By removing speech attribution, however, the narrative simultaneously offers Fanny’s views an alternative kind of freedom in that they can at least be voiced unmediated by a controlling or biased narrator. In parallel, the reader is equally undirected, free to recognize that the way in which the narrative appears to endorse its own message is also the way in which it destabilizes that message.

Mansfield Park clearly does engage with elements of the Evangelical novel, but any consideration of issues of ideology must be closely linked to the novel’s examination of didactic narrative structures that support that genre’s religious aims. A careful reading of Mansfield Park also reveals that its narrative complexity means that we cannot accept it as a straightforwardly homiletic narrative in the same way that most Evangelical novels are. Mansfield Park, far from being Austen’s most didactic novel, actually eschews Evangelical fiction’s certainties in favor of a narrative that encourages and validates more careful reading—reading that reveals what John Mullan calls “the small important complications of life” (4).

NOTES

1For a more thorough engagement with this issue see also Penny Gay’s Jane Austen and the Theatre, Joseph Litvak’s “The Infection of Acting: Theatricals and Theatricality in Mansfield Park,” and John Halperin’s “The Trouble with Mansfield Park.

2The revival of the Evangelical religious movement is outlined in David Bebbington’s Evangelicalism in Modern Britain. The scope of Evangelicalism’s influence during the late-eighteenth is exceptionally well documented in Peter Knox-Shaw’s Jane Austen and the Enlightenment.

3For a comprehensive and subtle exploration of Austen’s religiosity, see Knox-Shaw. For a reading that stresses the importance of the letters as evidence for Austen’s support for Evangelical ideas, see also Robert Clark’s “Jane Austen and the Moral Empire.”

4Colin Pedley notes that there is “little unanimity of view” of the importance of the theatricals to the novel as a whole (297). It would be impossible to offer an definitive overview of the debate, but a number of differing viewpoints are offered in Katie Halsey’s Jane Austen and her Readers, 1786–1945 (83); Margaret Kirkham’s Jane Austen, Feminism and Fiction (95); Litvak’s “The Infection of Acting: Theatricals and Theatricality in Mansfield Park”; A. Walton Litz’s Jane Austen: A Study of her Artistic Development; David Lodge’s “A Question of Judgment: The Theatricals at Mansfield Park”; and Lionel Trilling’s The Opposing Self: Nine Essays in Criticism (181–203).

5A similar point is made in Massimiliano Morini’s Jane Austen’s Narrative Techniques: A Stylistic and Pragmatic Analysis.

6For a balanced middle-way between the extremes of historicist and formalist approaches, see Norman Page’s The Language of Jane Austen.

7For an illuminating study of the development of literary description of objects, including emblematic ones, see Cynthia Sundberg Wall’s The Prose of Things.

8Austen’s use of style indirect libre can be so subtle that the shift from omniscient narration to focalized narration is often, as Peter Knox-Shaw acknowledges, “scarcely perceptible” (14).

9For an excellent discussion of Austen’s ingenuity with free speech, see Toner’s “Free Speech: Jane Austen, Robert Bage, and the Subversive Shapes of Dialogue.”