Between 1938 and 1967, there have been ten television adaptations of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. One of the most freely adapted takes on the novel is no doubt Orgoglio e pregiudizio, an Italian TV series in five parts made by the RAI in 1957. At well over 300 minutes, it was for a long time the lengthiest version ever made—until the 1995 BBC series came along. Orgoglio e pregiudizio was a lavish spectacle, for its time, using large sets and including scenes with many extras (e.g., a military parade and a village dance).

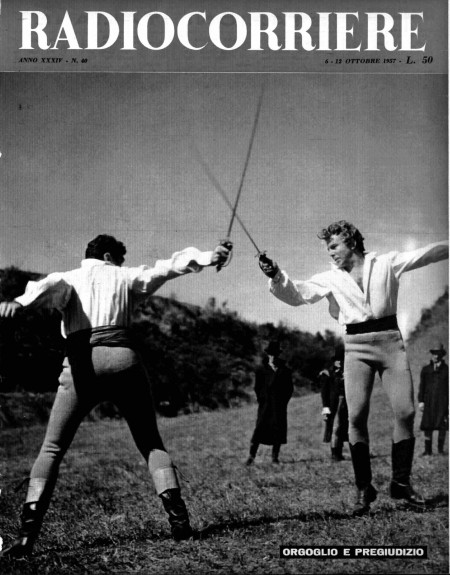

But unlike the BBC version, length in this case does not equal closeness to the source material. In the opening scene for example, Darcy and Wickham fight a duel with swords. This event, which served as a teaser before the opening credits, is illustrative of the serial’s whole approach: it was not afraid to make alterations, and it sets up the rivalry between the two leading men as prominently and actively ongoing from the first moment. Its events are also played out directly before the camera rather than presented to us by indirect reports of stories of past grievances. These differences make for a take on Pride and Prejudice that we haven’t seen before, one that is less true to the pages of the book and may also contain a few surprises.

The duel between Darcy and Wickham on the cover of Radiocorriere (September 1957).

There are in fact only three non-English television serializations of the novel, all made in a space of ten years between 1957 and 1966.1 The Dutch De vier dochters Bennet (1961–1962) was based on a BBC screenplay (Wels, “De vier dochters”); the only other Mediterranean version was the Spanish Orgullo y prejuicio (1966), which, filling ten half-hour slots, was also quite long but is now lost (Romero Sanchez). Unlike the Dutch series, Orgoglio e pregiudizio was made completely independently from any earlier attempt; as such it covered fresh ground and was thus able to make its own rules and provide its own reading of the story.

Background

In 1957 the RAI was the only station in Italy, and its television service was just three years old; Italian television had started regular transmissions in 1954. Earlier in 1957 the RAI had shown Jane Eyre, and it would later that year follow up with performances of many other masterworks. Orgoglio e pregiudizio is not identified as part of a larger series, but the RAI at this time regularly included works of international literature, and its programming might therefore almost be considered to present an anthology series of sorts. In the previous year it had, for example, broadcast its production of Wuthering Heights, Cime tempestose. By coincidence, both Dutch and Spanish public television presented adaptations of both stories in the same order in the sixties. Orgoglio e pregiudizio aired on the RAI on Saturdays from September 21 to October 19, 1957, at 9 o’clock in the evening. The episodes were performed live, except for a very small amount of pre-recorded footage. The output was recorded on film (video tape had not yet been invented) and was rebroadcast early on Wednesday evenings between July 2 and 30, 1958.

Virna Lisi as Lizy Bennet.

Orgoglio e pregiudizio (1957).

Virna Lisi portrayed Lizy Bennet, Franco Volpi played David Darcy, and Enrico Maria Salerno was Wickham, with Daniele D’Anza directing. The principal actors, the director, and the script writer all have many, many credits to their name, often in other, similar literary or historical adaptations. Orgoglio was for most of them an early point in their long careers—perhaps hardly surprising because, after all, television had only just been introduced in the country. The only exception is the screenwriter, Edoardo Anton, who was also active in the Italian movie industry and who had been producing screenplays since the thirties. But for Lisi and Volpi it was one of their first leading roles; Salerno had had one or two central roles on television before. Luisella Boni, Lydia, had played in over a dozen movies; she would later marry Daniele D’Anza, the director. She perhaps looks a bit too old for the role, but in reality she was only one year older than Virna.

For a quarter of a century after the repeat of 1958, the program apparently remained unseen. In the 1980s, Orgoglio e pregiudizio experienced a small revival. It was shown on afternoons between January 25 and February 1, 1984; September 15 to 19, 1986; and again between November 3 and 9, 1987 (although that last broadcast may have been the 1980 BBC version). An official DVD was released in 2008, along with the RAI’s Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and other literary classics; it was reissued in 2018. Although the DVD has no subtitles, fan-made Italian transcriptions as well as an English translation can be found online. The RAI also currently offers the program online for free to those located in Italy. The online version is slightly different from the DVD because the former occasionally briefly loses its sound (e.g., when Lizy is rebuffing Mr. Collins’s advances). The DVD smoothed things out by simply cutting off before that point; it also adds a caption to episode three in order to briefly explain a few clearly missing events. (The loss of audio is caused by reel changes in the film on which the episodes were archived.) In addition, an early version of Anton’s scenario is archived in an Italian library.

Orgoglio e pregiudizio

Episode 1 (September 9, 1957):

The pre-title sequence depicts a swordfight between Darcy and Wickham.

After chaos in the Bennet household, its ladies head for a ball that Mr. Bingley is hosting at Netherfield; Lizy overhears the slight from Darcy, and she retaliates by refusing to dance with him later. Wickham (whose name is not mentioned) afterwards visits Bingley to borrow money to pay off a gambling debt, admitting to a troubled relationship with Darcy (in this version his stepbrother). On her way to Netherfield (on foot), Jenny is surprised by the rain, with Lizy just behind her bringing an umbrella. When Jenny falls ill upon arrival, Lizy is forced to stay as well. Caroline Bingley points out her horror at Lizy’s bad manners and their mother’s provincial behavior, which signals a lower status; however, Caroline is unable to make her brother dislike Jenny. Conversation between Darcy and Lizy all but reveals that he is in love with her.

Episode 2 (September 28, 1957):

The pre-title sequence depicts Mrs. Bennet visiting Jane at Netherfield and saying all the wrong things.

Cugino (Mr. Collins).

Orgoglio e pregiudizio (1957).

The arrival of pompous cugino (cousin) Collins prompts a lengthy exposition about the entail. Since he only has three days, he and Mrs. Bennet get to business much more directly. Wickham makes Lizy’s acquaintance and spins his tale about how badly Darcy has treated him. At home, Lizy keeps evading Mr. Collins, eventually steering him towards Charlotte. Meanwhile Darcy fears that Bingley’s affection for Jenny is becoming too serious; when he talks about it to Charles later, it’s hinted that he might also be projecting his own feelings for Lizy. Wickham confronts Darcy outside after aparty. Wickham hints of a scandal that Darcy will want to keep secret and also accuses him of having treated him as an inferior throughout his childhood. Mr. Collins is revealed to be already engaged to Charlotte, but the Bennets are not yet aware of Bingley’s departure.

Episode 3 (October 5, 1957):

Lady Katherine.

Orgoglio e pregiudizio (1957).

Elizabeth and Jenny receive from Caroline the bad news that the Bingleys won’t be back anytime soon. Aunt Gardiner and Lizy advise Jenny to write to Bingley, but Caroline destroys her letter. Jenny does not go to stay in London, but Lizy and Sir William Lucas still go to visit the parsonage at Hunsford. Wickham is briefly revealed to be already wooing Miss King and her fortune (one of the few events that is included, but not elaborated upon). At Rosings, they find Lady Katherine ordering people about even more explicitly than in the novel. Lizy earns the respect of Colonel Fitzwilliam by speaking up to Lady Katherine. To Lizy’s great surprise, Darcy had in fact visited Longbourn on his way to Rosings from London, only to find that she would be at his aunt’s. At this point the episode cuts off (see the section on missing footage, below), depriving the modern viewer of Darcy’s first proposal and Lizy’s rebuttal.

Episode 4 (October 12, 1957):

We find Lizy in the coach with Sir William Lucas, on the way home, in her thoughts reproaching herself for her lack of judgment; apparently Colonel Fitzwilliam set the record straight on Darcy and Wickham. Back at Longbourn, at Elizabeth’s insistence, Mr. Bennet forbids Lydia from going to Brighton. Darcy unexpectedly returns to Netherfield with his sister, followed by Bingley. Things are looking good, with Lizy and Darcy even playing four hands at the piano, when Lydia elopes with Wickham. Darcy traces him to a gambling den and confronts him. Although a drunken Wickham threatens all sorts of violence, even against Lydia, in the deal that they make there is a new element of forgiveness: it represents a reconciliation between Darcy and his jealous, rebellious stepbrother—although a purse of money is still needed to seal the deal. The Bennet family, unaware of what the viewers have already seen, is astonished to receive the good news.

Episode 5 (October 19, 1957):

The episode opens with Mr. and Mrs. Wickham’s visit to Longbourn. As in the novel, Lydia eventually lets slip that Darcy was behind the marriage. Darcy, returning with Bingley, finally reveals his sister’s secret, the near elopement, that was hinted at in episode 1. Lizy now accepts his proposal. In a merry sequence, he joins the village in dancing at the local harvest festival. Lady Katherine now pays her visit. As she leaves again in her coach, however, Darcy stays behind, confirming his choice. At last, after Mr. Collins has said a blessing on the coaches of the two newlywed couples, Mr. Bennet finds himself consoling his wife, who is sad to find the house so empty.

Darcy and Lizy. Orgoglio e pregiudizio (1957).

Jenny and Bingley. Orgoglio e pregiudizio (1957).

Missing footage

The survival and condition of the program require some attention. The episodes that we have today are of significantly unequal length, odd and even. The first and last parts are just under 50 minutes, while the second and fourth parts are between 65 and 70 minutes. The third installment was originally longer but now, unfortunately, cuts off at 42 minutes. A considerable portion of film has been lost, robbing us of a crucial scene: Darcy’s first proposal and Elizabeth’s refusal, followed by the revelations regarding Wickham’s and Darcy’s true characters. When normal service is resumed with the fourth episode, these events are over and done with. One revelation seems not to have been made: the true nature of the relation between Darcy and Wickham, which Wickham had alluded to when first confronting Darcy and which involves Giorgiana, will only be revealed halfway into the final episode.

Television schedules represent the third “puntata” as lasting 65 minutes, broadcast from 21:00 to 22:05. It should be noted that this source of information isn’t totally reliable: in general one hour was simply the designed time slot; the time tables give the first episode more but the second and fourth parts less time than they currently run. The final episode was scheduled to last until 22:10 but did not use its last twenty minutes.2 When the series was resurrected in 1984, its time slot was 50 minutes, suggesting that, whatever happened to episode 3, the damage had by that time been done.

It is something of a miracle that most of the series still exists at all. During the fifties, a repeat usually meant a repeat performance. Luckily for us, the Italians recorded and kept the recordings of literary works that they were adapting at this time (their Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, for example, survive as well). Renditions elsewhere were not so lucky: out of ten versions of Pride and Prejudice made worldwide between 1938 and 1967, only four still exist, and the Italian is the oldest but one (Wels, “First and Last Impressions”). The remaining material of Orgoglio e pregiudizio is at times rather scratched and has sound problems in one or two places, usually (but not exclusively) near the start and end of a reel.

Under these circumstances, it is quite possible that the first episode originally lasted longer as well. On both broadcasts, it seems to have had a larger time frame at its disposal. The video currently cuts off rather abruptly after 47 minutes, without any closing caption “fine della puntata” in the way that the others (2, 4, and 5) have. There isn’t any obvious discontinuity, and the story up until then includes some scenes from the novel, such as Caroline’s commenting while Darcy is trying to write a letter, as well as some new inventions, such as a conversation between Darcy and Lizy about choosing a book. At first glance, nothing essential appears to be missing.

Or is there? While the novel is thus covered up to chapter 10, some material from chapter 11 and later is unused, even though the stay at Netherfield is important as the starting point of not one but two romances, as well a chance for Lizy to display her wit and vivacity. And as seen before, this series does not shy away from adding new material; events could easily have been elaborated upon. In addition, one or two plot lines remain unfinished: does Wickham repay the money he borrowed from Bingley? Neither do we see Lizy and Jenny leaving for home again—a potentially valuable scene for revealing the different responses of each of the characters. It’s implied in a one-minute pre-title sequence of the next episode that, differing from the novel, they return with Mrs. Bennet after her visit. To modern eyes, a small jump skipping their departure isn’t abnormal; but, when held against the slow and continuous storytelling of the rest of this serial, it surely must be. Finally, in episode 3, Colonel Forster refers to a bet on Miss Bennet that was apparently made by Wickham that we never witnessed.

It is therefore my belief that the end of the first episode has been lost as well and that the serial originally consisted of four parts running nearly 70 minutes each, followed by a 50-minute finale. Certainly, the fifth episode seems to have exhausted all possible venues and could not possibly have been longer. Its slow pace serves to illustrate perfectly how unusually quickly the first episode concludes in comparison. The last reel of the first episode may have met with some sort of accident—when or how is unknown.3 In this case, the pre-title sequence of the second episode, Mrs. Bennet’s painfully embarrassing visit to her daughters at Netherfield, must have originally belonged to the first instalment. None of the remaining episodes starts with a pre-title sequence; even without the pre-title sequence, the second episode is the longest of them all. Episode 2’s pre-title scene opens rather abruptly and may have been salvaged from an otherwise unusable final reel of part one; most of the material that might have once been in episode 1, such as the departure of Jenny and Lizy from Netherfield, must have come (chrono)logically after this scene. The cut from there to the opening credits is not a dissolve as before but happens via a “wipe” to black, followed by a fade-in; it could easily, therefore, be a later edit.

A copy of Anton’s original screenplay is archived at the Biblioteca Museo Teatrale S.I.A.E. (Società Italiana degli Autori ed Editori). This screenplay, however, appears to be an early version: “Puntata 1” contains, for example, the domestic chaos when the Bennets leave for the ball as in the existing video but not the duel or the money lending. In fact, the screenplay contains almost none of the newly invented scenes that appear on screen. As such, it is too different from the final cut to support any conclusion. There is a scene resembling the pre-credits “teaser” of part 2, but that is the end.

The script for puntata 2 picks up the story during a piano lesson exactly as the broadcast does after its opening credits. But the script for this episode is, on the whole, much closer than the first one to the end product, in both scenes and dialogue—save, again, for a scene that was added later, wherein Wickham confronts Darcy and blames him for his childhood traumas. As a result, this evidence neither confirms nor excludes a longer first episode.

Missing persons, places, and plots

Despite the record length of this production, a number of people and places that appear in the novel did not make it to film. To start with, the Bennet daughters have been rearranged a bit: from eldest to youngest, Lizy, Jenny, Lydia, and Mary; Kitty has been eliminated, although Mary has been redefined as somewhere between Mary and Kitty. Mary’s main function in the story is to follow Lydia and to attempt to play the piano. Omitting one of the sisters is in fact quite usual in early adaptations (Wels, “First and Last Impressions”). Orgoglio e pregiudizio devotes very little screen time to the younger sisters anyway: with the exception of Lydia’s eventual elopement, their lack of decorum is not much shown or dwelt on, at least not in the copy that survives; it’s principally their mother who constitutes an obstacle to Jenny’s eligibility. Bingley has only one sister. Less usual revisions include the change of Darcy’s first name to David, and George Wickham’s becoming Robert.

The four Bennet sisters. Orgoglio e pregiudizio (1957).

A second and more drastic elimination is the reduction in the number of locations. Here, the reasons for the restriction are mostly technical. Although the cameras are sometimes surprisingly mobile, giving us more dynamic shots than we might have expected for 1957, the number of studio sets was nevertheless limited. Two sets per episode seem to have been the maximum. As mentioned earlier, the broadcasts were almost entirely performed live. The only way to supplement the real-time output was through the use of pre-recorded film, the so-called “filmed inserts.” While there are some of these (the opening duel is one), they’re very few and very short, and they’re limited mostly to those scenes that are truly outside and that involve coaches—no doubt because horses cannot fully be depended upon. Clearly the use of pre-filmed sequences was kept to an absolute minimum; similarly it was necessary to cut back on the number of studio locations.

Places that we do see are the interiors of Hunsford and Rosings and, later on, the place where Wickham and Lydia hide. Exteriors are of course more difficult. Bits of street can still be filmed in the studio with the help of backdrops. Rosings, on the other hand, is only seen indirectly: the company at Hunsford admires its grandeur with a telescope, commenting to each other. But the new medium of television was meant above all to show things to the viewers. While using the characters’ reaction was the only workable solution to get Rosings into the story, Orgoglio e pregiudizio, as a rule, declines to repeat this trick or to present any parts of the story indirectly. The series tries its best either to show or not to include at all. In other words, it avoids as much as possible the practice of informing us of events that take place elsewhere—for example, by means of letters or other reports. In contrast to the technical limitations, this choice is deliberate.

The TV series thus entirely removes everything that can’t be shown, such as the events that take place in Cheapside in London or in Brighton and also, most importantly, Lizy’s holiday with the Gardiners and their visit to Pemberley. The storyline dispenses with these travels by working around them. Out of necessity, that last example (an important development in creating the right conditions for a new meeting between Lizy and Darcy) has been supplanted by Darcy and his sister’s becoming the new occupants of Netherfield. As a result, the story is focussed on fewer locations; too much movement was simply not an option, and neither were regular outdoor shots.

Finally, another significant victim of the limits of technology is dance. Needless to say, dancing is an important element of the novel: dance was at the heart of the ball, and balls were crucial events for eligible young ladies such as the Bennet sisters. But although all societies dance, without technological refinement it is difficult to televise the result; the cameras and the microphones simply weren’t capable of following all that movement. In this case, in episode 1 the ball at Netherfield takes the place of the public assembly, and a party at Longbourn substitutes for Austen’s Netherfield ball in episode 2.

Orgoglio e pregiudizio isn’t the only rendition that has had to work around the dancing: a Canadian adaptation one year later was forced to do the same, and a 1949 version from the U.S. only managed to include conversation from the dance floor by resorting to a very stationary waltz indeed (Wels, “First and Last Impressions”). The Italians managed to stage the dancing much better in episode 1; here we get several lines of dialogue from the couples on the floor. In later episodes, however, the pleasures of the dance have to be dispensed with, save for a slightly silly village dance in episode 5.

Missing irony

There is a one striking difference in the dialogue of the story. Jane Austen’s ironic style does not fully carry over. Although the irony has not fully evaporated, it is not at the strength that it in the novel or in other adaptations. The best examples are no doubt the protagonists: Virna Lisi’s performance has energy, vivacity, and involvement, but Lizy’s dialogue is at times less verbally witty. Another case is the beginning of the story and the character of Mr. Bennet. While he and his wife still bicker and argue, the script does not include the revelation that he had secretly visited Mr. Bingley while pretending to refuse to do so—an opening scene that has been duly included by all other television treatments existing on video or in script form. Instead, Mr. and Mrs. Bennet display a love–hate relationship that is played through her volume and his patience. Later on, familiar conversations take place between Lizy and Lady Katherine, but again their opinions (or orders, in the case of Lady Katherine) are more overt and less veiled in decorum.

Mr. Bennet. |

Mrs. Bennet. |

At other times the subtext is still more or less intact, for example during the stay at Netherfield, although a few sentiments are expressed more explicitly. Fidelity to the text varies greatly throughout the series. Although some phrases from the novel duly appear, as well as the gist of some scenes, albeit with different lines, the style of dialogue is often very different and more intense. The completely new content has a slightly different angle, and does not specifically add up to any conclusion. These moments—mostly involving Wickham—convey what is troubling the characters inside, although with less structure: they belong to a different time. Wickham’s appearance at Netherfield to borrow money from Bingley, for example, does not make as much logical sense as Jane Austen’s own storylines.

At any rate, despite (or because of) the somewhat diminished level of irony, the series is in general very wordy. Everything is discussed at great length, both the events narrated by Jane Austen and a significant amount of additional conversation for new scenes and dialogue she did not write. While the story may move a bit more slowly, its characters definitely have more to say to each other. Thoughts and emotions are spoken aloud. This change is not necessarily due purely to the translation from “English composure” to “Italian temperament”: it’s also a matter of moving from a book with a narrator to a medium with direct speech only. The loquacity is in fact what makes this series one of the longest renditions—unlike the even longer 1995 BBC series, which, being shot entirely on film, had the means to include splendid sights, interior and exterior, and therefore didn’t need to rely solely on speech. An adaptation with serious change of tone had been made once before, though in a much shorter version, in a 1956 American TV episode of NBC Matinee Theater, which currently survives only in script form (Wels, “First and Last Impressions”).

The extra scenes in Orgoglio also change the development of the story for the viewer, as compared to the reader. While the narration of the novel generally stays with Elizabeth, this TV version moves the perspective closer towards the omniscient. Consequently, while verbal irony is less prevalent, there is on the other hand a slight increase in dramatic irony: Wickham’s early introduction gives the audience a head start over Lizy’s perception of him. In that sense, the presumably missing end of episode 1 might be more important than it seems. An extra appearance of Wickham there could determine our prejudice as viewers when he is introduced to Lizy in episode 2. Only archival records of the RAI, if they should turn up, could provide the definitive answer.

Crisis: David Darcy versus Robert Wickham

Despite my emphasis on what has disappeared, Orgoglio e pregiudizio isn’t all a vanishing act; on the contrary, the series boldly added many completely new scenes. Some, such as the visit of the piano teacher or public events in the village, have no crucial impact. Others, like a discussion in the stables between Bingley and Darcy in episode 2, may offer a twist or a different approach; in this case, Bingley almost suspects that Darcy is running away to save himself from Lizy.

There is one aspect, however, that the writer drastically expanded and re-envisioned: the relationship between Darcy and Wickham. While some smaller embellishments already appeared in the early version of the script, this new motif did not. Although the conflict is recognizable, it is much more continuously represented in this adaptation than it is in the novel. The choice for a duel as the opening scene of the series is telling: when Darcy declares, “For me, the match is over,” Wickham replies, “For me, this duel is over. The match starts now.” As we find out in episode 2, Wickham has additional grievances, of a new, different kind: namely, the humiliations that he suffered in his youth. Testifying to his hatred, he accusingly sums up his limited “rights” as a child of ten: helping Darcy onto his horse, getting only hand-me-down toys, and having to be grateful for his support without ever crying. In practical terms, this change of emphasis means more screen time for Wickham, who now appears in every episode of the series. The social inequity (it would be far too much to call it a class struggle) is not revisited during the rest of the series.

As noted earlier, the new material does not always serve the purpose of a specific storyline; rather, it draws attention to emotion, specifically the inner life of the characters and what ails them. Viewed in this light, the difference is always visible (albeit with the considerable hindsight benefit of knowing what is new). The most obvious explanation is that more male screen time was decided on after Edoardo Anton had completed the initial screenplay, simply to make sure the series was palatable to Italian men as well as women. As a result, this line of additions (to both the story and the earlier script) was not integrated into the plot; in other words, removing these scenes would not affect the rest of the program.

Anton’s Wickham appears tragic at times to the point of existentialism. His dialogue sometimes turns to monologue about his inner troubles—even though he is still as weak of character as ever. Perhaps Darcy really did reduce him to poverty, leaving him no real choice other than to turn fortune hunter? When in part 4 he threatens Darcy with inflicting violence on Lydia, he seems as much desperate as villainous. Darcy, however, rescues them from themselves and can finally end the feud with Wickham because of his newfound modesty, which allows him to forgive the failings of others. Wickham’s character sees less development: he undoes his new touch of fallible humanity by waxing lyrical over a purse of money in the scene that follows. Lydia, too, might actually love Wickham at that point, even if we are not sure of him. But episode 5 sees them return to true form when they visit Longbourn, fully in the spirit of the novel. In the end, in keeping with Jane Austen, there is no real salvation for the Wickhams after all: they’ve made their own proverbial bed.

Epilogue

Orgoglio e pregiudizio is in fact a double translation. First of all, it converts a novel to a television series, a process that is more specific than just combining words with sound and image. The translator/script writer did not have a free hand: on the contrary, he had to meet technical requirements that limited what could be staged.

Secondly, the story is translated not just into another language; in a wider sense, it is also transposed onto another culture and another time. Here, the script writer was able to take whatever liberties he deemed necessary, and he was not afraid to become creative. The concerns and other defining characteristics of the characters have been modified to better resonate with the Italian audience; similarly, the entirely new scenes—although they are not directly anachronistic—belong stylistically more to the 1950s than the 1800s.

Promoting the role of male rivalry and developing Wickham’s part were significant to this multi-layered translation. The stepbrotherly enmity, an expansion of their original rivalry for Elizabeth’s affection, becomes a consistent theme throughout the series, beginning with the duel. In addition to increasing the masculine element, this tension was probably introduced to heighten the series’ emotional load in general—not an unusual move for Austen adaptations (Wels, “De vier dochters”). It is here that we can detect a modern emphasis on inner motivations.

Taken scene by scene, Orgoglio e pregiudizio employs three gears on its way through the novel: more or less faithful renditions; differently styled dialogue for existing scenes; completely new material. Despite the fact that several elements of the novel disappeared one way or another from Orgoglio e pregiudizio, it may not be productive to see that as a type of criticism. Most omissions were simply necessary in a time when television technology was still in its infancy and there were technical limits to filming dances and exteriors. An original, Mediterranean, and at times even almost existentialist take on the novel must be valued as a welcome innovation. With the verbal ice more above the waterline than below, Orgoglio e pregiudizio uses less irony but speaks more directly to the viewer. Translation, in other words, meant three things: it did not just entail semantics (the translation proper); it also meant crossing a cultural divide; and it involved a jump forward through time of almost 150 years. These changes of style, however, do not invalidate the result. After all, when Jane Austen wrote the novel Pride and Prejudice, it wasn’t a costume drama; it too was a contemporary story.

NOTES

1Compare the seven English-speaking versions between 1938 and 1967, which are covered in Reinier Wels’s “Pride and Prejudice in Black & White: First & Last impressions (1938–1967).” This number excludes adaptations that relocate the story in time and place.

2I take the programming schedule of the repeat to be more accurate than that of the premiere, which must have been prepared for publication in advance of the recording itself, meaning the precise runtime wasn’t known yet.

3Neither the RAI nor Centauria, the publisher of the DVD, was able to either confirm or deny my hypothesis.