The production of fan fiction has accompanied Jane Austen’s popularity since its resurgence in the 1990s.1 Besides many online communities in which fans can write and read sequels, variations, modern retellings, slash fiction, mash-ups, etc. to their hearts’ content, there is also a growing market for these stories at large online bookstores such as Amazon, made even stronger by the emergence of e-readers and the self-publishing system. A quick search of these websites will show that Pride and Prejudice is the novel generating the largest body of fan fiction—be it in online, paperback, or electronic editions—and by a very large margin.2 In fact, the conventions of the universe of Pride and Prejudice fan fiction affect the production of sequels and variations for Austen’s biography (see Biajoli) as well as her other novels and, as I intend to demonstrate here, for Sanditon’s continuations.

A close analysis of fan fiction can provide us with insights into what fans value most about Austen and how they interpret her work, as these aspects influence and resurface in their own writings. Most Jane Austen fan fiction focuses on the love plot of Pride and Prejudice, on exploring the details of Darcy’s and Elizabeth’s feelings and relationship, and on trying to create happy endings for minor characters. This plot-driven reading emphasizing romance, sentiment, and a happily-ever-after marriage, and reinforced by the ways her novels have been adapted for television and film, overlooks Austen’s style, sharp irony, and social criticism. In general, this trend can be observed as well in recent Sanditon continuations: of all the many questions left unanswered by Austen, fan fiction tries to answer only one, the matters of the heart, disregarding the wit and satire of the manuscript.

According to the list provided by Mary Gaither Marshall, there are at least twelve continuations of Sanditon produced after the year 2000 and the emergence of the current Austenmania, a number bound to change because of the self-publishing system and the increasing number of “vanity presses” that publish stories written by fans. Among these twelve cases, this essay will focus on continuations that show how current writers, when working with a less commonly-known and unfinished source for their stories, nevertheless maintain a dialogue with Pride and Prejudice fan fiction conventions: Sanditon (2004) by Juliette Shapiro, The Brothers (2009) by Helen Baker, A Return to Sanditon (2011) by Anne Toledo, The Suspicion at Sanditon (2015) by Carrie Bebris, and the five-volume series Girl Finds Eternity (2015) by C. M. Mitchell,3 the last two Sanditon and Pride and Prejudice mixed variations.

![]()

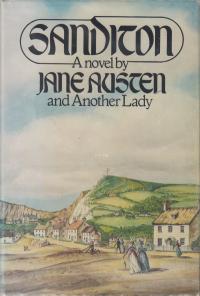

Before we address these interesting cases, it is important to establish that the novel held by many readers to be the best continuation of Austen’s manuscript is Marie Dobbs’s Sanditon: Jane Austen’s Last Completed Novel, published before the current wave of Austenmania, in 1975, and signed only by “Jane Austen and Another Lady.” In a search for Sanditon at Amazon.com, the first result is Dobbs’s novel.

Before we address these interesting cases, it is important to establish that the novel held by many readers to be the best continuation of Austen’s manuscript is Marie Dobbs’s Sanditon: Jane Austen’s Last Completed Novel, published before the current wave of Austenmania, in 1975, and signed only by “Jane Austen and Another Lady.” In a search for Sanditon at Amazon.com, the first result is Dobbs’s novel.

Online reviews provide further indication of the acceptance of this continuation.4 Of the seventy-four reviews of the novel, available at Amazon.com, eighty-four percent are positive, rating it four or five stars out of five.5 Nearly half of these reviewers justify their appreciation on the basis of Dobbs’s writing style, which is perceived as very similar to Austen’s. Readers said they were unable to locate the exact point of the transition between the two authors. Also, many believed that Dobbs developed the characters and plot as Austen might have done, considering her as faithful to the original as possible. For example, Mr. Parker remains obsessed with the prosperity of Sanditon, the Parker sisters hypochondriacs, Lady Denham tightfisted and demanding, Sir Edward a fool—to the point of kidnapping someone during the day in an open gig.

Although there is not a strong indication in the manuscript that Sidney Parker was meant to be the hero, Dobbs paired him with the heroine, Charlotte Heywood, the feasibility of which is still debated among critics. We are told in Austen’s version not much more than that he is “‘a very clever young man, and with great powers of pleasing’” and “a decided air of ease and fashion and a lively countenance,” and that he says anything he chooses and laughs openly at his siblings (Later Manuscripts 158, 207, 158). According to Marshall, Sidney was also Anna Lefroy’s choice for the role of the hero in her own attempt at finishing the manuscript around the years 1845–1855; since Austen might have discussed Sanditon’s storyline with her niece, Lefroy may well have had knowledge that Sidney was indeed intended for Charlotte. Even if Dobbs got this one right, however, she also made choices for her hero that do not resonate with Austen’s work. For example, she developed Sidney in a way very similar to Frank Churchill: as someone who enjoys directing other people’s actions according to his own (hidden) ends, except that the secret engagement Sidney is protecting is not his own. Although Sidney’s manipulations achieve the happy ending for Clara Brereton and her secret fiancé, interfering in the romantic lives of others—as do Frank Churchill, Emma, and Mr. Darcy—is not depicted in a positive light in Austen’s novels. We need only remember Mr. Knightley’s dismay: “‘He has used every body ill—and they are all delighted to forgive him’” (Emma 467). But such inconsistencies have not dislodged this continuation from its privileged place for Austen fans.

![]()

How do recent continuations build upon Marie Dobbs’s version? Helen Baker’s The Brothers (2009) is very similar to Dobbs’s continuation in solutions and style, but it didn’t attract enough attention to prompt readers to post reviews on Amazon.com. (Perhaps fans of continuations and adaptations were more concerned with the publication of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies in that same year or were indulging in the new TV adaptation of Emma.) However, the intertextuality with Dobbs’s novel is remarkably clear, as in the following excerpt in which a caricature portrait of the Parker family drawn by Charlotte Heywood, here an accomplished artist, is described:

“There is Diana winding a second scarf around Arthur, while he snatches another tart from the table behind her back,” [says Mr. Parker].

“I am trying to stop Susan dosing little Mary and tipping some of her drops out of the nursery window . . . ,” laughed his wife. “Meanwhile you, my dear, are inspecting your plans for the construction of an improved Royal Pavilion at Sanditon—well really! But what is Sidney doing . . . ?” High above Sanditon, sitting on a cloud, a smiling Sidney Parker pulled on the tangled strings of his brothers and sisters, like a demented puppeteer. (Kindle position 3855)

This is clearly a rendition of Sidney Parker’s manipulative personality according to Dobbs—even if he has the best of intentions. A blog dedicated to Austen sequels defends the many merits of Baker’s work, quoting this passage as an example of its quality (Adams). In my opinion, however, the reviewer values this excerpt because it fits the 1975 version, rather than what Austen left us.

![]()

It might be another effect of Dobbs’s version that the romantic plot in all the Sanditon continuations analyzed here focuses on Sidney Parker and Charlotte Heywood—or at least they are one couple happily matched among many others, as in C. M. Mitchell’s series. It is curious, to say the least, that no one has dared to pair Charlotte with another gentleman. But Sidney, we are told in Austen’s version, is intending to bring some friends to Sanditon, so could the hero be one of them? In truth, it doesn’t matter. The “fanon”—or the conventions constructed by fans in the fan fiction universe—has already dictated some of the conventions of continuations. Mr. Darcy, for example, must look like Colin Firth: we can read a story in which Darcy is gay, but a blond Darcy is inadmissible. In Bronwen Thomas’s words, it is through repetition that “certain plot or character elements become established within the fan community—even when those elements never appeared in the source text, or radically depart from it” (8). Sidney and Charlotte are always designed for each other. We can see that Dobbs’s continuation works, then, as a strong basis for the fanon regarding Sanditon. And if Sidney Parker was indeed created by Austen to be the hero, then we can appreciate Austen’s talents even more when we recall the scene in which Charlotte meets him for the first time and in which we don’t hear the words they exchange. This scene couldn’t be further from the conventions of “love at first sight,” yet Austen has somehow become the mother of romance. One would think that by not having the traditional happy ending, or any ending at all, Sanditon would be able to escape Austenmania’s obsession with love plots, but it does not.

![]()

While Dobbs’s continuation, then, is the first model that acts as a reference for readers to evaluate newer Sanditon continuations, the second source, no less influential, is the Jane Austen Fanon, which is highly determined by Pride and Prejudice fan fiction. In a previous study of Pride and Prejudice inspired stories, I was able to perceive patterns or aspects that are common, accepted, and even expected by readers.6 These continuations focus on the courtship between heroine and hero, particularly on their love story and happy ending, usually with much drama and sentimentality. Deidre Lynch remarks that these stories “often feel, in their sensationalism, strangely pre- rather than post-Austenian” (164–65). For example, frequently the role of the main character is given to Mr. Darcy (rather than to Elizabeth). The Darcy of fan fiction goes through a process of “correction” so as to have no pride, no negative traits. He is courageous, kind, honorable, incredibly handsome, and sexy, and his rudeness and officiousness are deleted, moderated, or justified by his shyness and desire to protect his loved ones.7 Since a hero will always need a nemesis, Mr. Wickham becomes the true villain, the opposite of Darcy in a dualistic structure where good is really good and bad is really bad. One is reminded here of what Jane Austen mocked in “Plan of a Novel,” her script for a future novel that collected absurd suggestions from different people: “all the Good will be unexceptionable in every respect—and there will be no foibles or weaknesses but with the Wicked, who will be completely depraved & infamous, hardly a resemblance of Humanity left in them” (LM 228). Ironically, given what Austen herself laughed at, fan fiction’s Wickham is typically bad: in Deborah Ann Kauer’s variation he plots and schemes, he is violent, and he even organizes a gang-rape of Lydia.

In the Sanditon continuations, some of these solutions applied to Darcy and Wickham appear in the character of Sir Edward, who is often transformed into a perfect man or a perfect villain. In Austen’s manuscript, Charlotte judges him to be a “downright silly” man (176), who “had read more sentimental novels than agreed with him”: because of “a perversity of judgement, which must be attributed to his not having by nature a very strong head, the graces, the spirit, the ingenuity, and the perseverance, of the villain of the story outweighed all his absurdities and all his atrocities with Sir Edward” (183). Austen here revisits Northanger Abbey’s theme but shows that the usual condemnation of her time—that novels were a risk to the impressionable minds of the fair sex—is as ridiculous as Sir Edward himself, whose “great object in life was to be seductive” (183) and whose chosen victim is Clara Brereton, his rival for Lady Denham’s inheritance:

If he were constrained so to act, he must naturally wish to strike out something new, to exceed those who had gone before him;—and he felt a strong curiosity to ascertain whether the neighbourhood of Tombuctoo might not afford some solitary house adapted for Clara's reception;—but the expence, alas! of measures in that masterly stile was ill-suited to his purse. (184)

This passage is very similar to another excerpt from “Plan of a Novel,” in which Austen describes the fate of her perfect and innocent heroine:

Often carried away by the anti-hero, but rescued either by her Father or the Hero—often reduced to support herself & her Father by her Talents, & work for her Bread;—continually cheated & defrauded of her hire, worn down to a skeleton, & now & then starved to death.—At last, hunted out of civilised Society, denied the poor Shelter of the humblest Cottage, they are compelled to retreat into Kamtschatka. (LM 228)

Here Austen registers her lack of patience with sentimentalism, unlikely adventures, and exotic locations, all of which are found in Sir Edward’s not very strong head.

In Anne Toledo’s A Return to Sanditon, however, Sir Edward is cured of it all, in a similar process of “correction” as that applied to Darcy but with a different outcome. While Darcy is modified to become the perfect hero, Sir Edward is slowly changed into a sentimental character, now “an excellent young man” who genuinely loves Clara Brereton, even after she departs to London to start her own seamstress business. This recuperation is reinforced when Charlotte says to Clara that “Sir Edward is no fool” and feels for him: “Charlotte could not but admire him for the strength and steadiness of his affection, so unexpected in a young man who had initially presented himself in the guise of a Byron or a Lovelace” (Kindle position 3281, my emphasis). In this passage, Sir Edward is no longer that downright silly man but noble and honored, if not perfect, because of his taste in literature. The comicality of Austen’s character is lost—a problem if we consider how her genius shone through her other highly entertaining characters (Mr. Collins or Miss Bates, for example). As Sir Edward is corrected, then, not only he is developed in an unusual way in relation to Austen’s manuscript, but this continuation rejects the richness of Austen’s creation in the name of another happy ending.

There are other “corrections” in Toledo’s story, such as in Miss Diana Parker, who in Austen’s original is a lovely mixture of a comical hypochondriac and an annoying meddler but in Toledo’s version is finally, Charlotte realizes, sympathetic:

I have been unjust to Miss Diana. . . . I thought of her almost as a figure of fun, an eccentric spinster, with her hypochondria and her love of intervening in other people’s affairs. . . . I did not understand that under her fussy manner there lay a genuine desire to help others, even at the cost of considerable sacrifice to herself— . . . for not all her ills are imaginary. (Kindle position 3119–23)

It’s fair to note that this specific correction is not limited to Toledo’s attempt. Carrie Bebris, while maintaining the Parker sisters as hypochondriacs, makes them able to cure their little nephew’s pneumonia, showing that their medical knowledge at least is real.

Lastly, we have the case of Sir Edward’s sister, Miss Denham, who in Toledo’s Return is reformed “from a proud, cold and discontented young woman to a hopeful and animated girl” (Kindle position 1761–63). There are precedents for this kind of change as well, since in fan fiction even Caroline Bingley once in a while remedies her ways and is rewarded with a happy ending of her own (Wood).

These alterations may have affected Toledo’s reviews on Amazon.com, which are evenly divided: nine readers rating her novel with five or four stars, nine with between three and one. Among the positive opinions, three readers cite her faithfulness to Austen’s style, asking, “Is Jane Austen back?” or declaring her “the new Austen!”8 Austen remains the authority or the main reference for these reviewers: somehow they do not see Toledo’s corrections to the characters as inconsistent with the original. Eight people, however, disagree with the solutions and style in this continuation, claiming that Marie Dobbs’s version is still the best.

Despite Toledo’s improvement of Sir Edward, the most common treatment of his character is that applied to Wickham: his transformation into a villain. In Juliette Shapiro’s Sanditon (2004), Sir Edward is described as having an “elegant appearance [and] accomplished manners” but being “the epitome of dishonesty and selfishness” (78). He is a scoundrel who contracts secret engagements with Miss Lambe, Clara Brereton, and a third lady from a distant estate, all for money. Charlotte Heywood, in a letter to a sister, presents him as someone really dangerous—not the silly man we see in the original manuscript:

He is an expert on captivation, the very embodiment of all that is charismatic. He is attentive . . . poetic, well-mannered, and accommodating. . . . He is something quite spectacular in the way of appearance and attractiveness. But all this derives from nothing more than learned skills and applied appeal, he has no genuine sentiment, women are mere instruments to him, he knows how to play them well. (Shapiro 130)

This portrait is as different from Austen’s description as the “corrected” one, but it can be explained by the need of having a real rogue in the story. Curiously, Shapiro herself has stated that “this story, my personal resolution to the unsolved mysteries of Sanditon, is written with every intention of remaining faithful to Jane Austen” (1). It didn’t convince the readers, though, who judged this continuation “insipid,” “uninspired,” “poorly done,” and a disappointment:9 among eleven reviews, only three are positive, and six point out again that Marie Dobbs did a much better job.

The issue of fidelity to Austen is also behind one of Shapiro’s negative reviews, which called her Sanditon a “travesty” because, while this

version is written with a good amount of period knowledge, the author suffers from a lack of plotting and writing skills. It is clear when she diverges from the Austen text. . . . As well, added characters and plot lines appear from nowhere, overshadowing the original intent of the text. I appreciate Shapiro’s interest in completing Sanditon but it has been done with better skill and without insult to Austen in Sanditon by Jane Austen and Another Lady. (my emphasis)10

Again, while readers agree that Austen’s text must be followed, when there is no text—Sanditon is an unfinished manuscript, after all—Dobbs’s continuation will be referred to as a standard.

Helen Baker’s The Brothers follows the same path, presenting Sir Edward as a dangerous Lovelace, who seduces the youngest Miss Beaufort and would have eloped with her if not for the Parker brothers’ adventurous intervention in the middle of the night. This continuation not only creates villains, it also relies on the dramatic additions usually observed in Pride and Prejudice fan fiction. But the most extreme case is found in volumes 10 and 11 of C. M. Mitchell’s Girl Finds Eternity series. Charlotte Heywood “had been in error [about] the man behind the malicious romance. She thought him harmless. He was not” (10: 1181–83). In this series, Sir Edward actually abducts Clara Brereton and tries to rape her:

“However his lust and desire for carnal embraces could not wait until they reached an inn,” Mr. Darcy stated, “or perhaps he did not wish to go to an inn of course, because Clara could very easily get word to us while she was there, or tell anyone that she had been taken against her will.

“Therefore, Sir Edward thought it in his best interests to stop the carriage,” Colonel Fitzwilliam hissed, “He did so and took Clara to a set of woods. And that was where we found him, with her crying out for help and him not listening.” (11: 589–97).

As expected, the villain is defeated by the noble heroes Mr. Darcy and Colonel Fitzwilliam. In Elizabeth’s words: “All thanks to our chivalrous men, who came to her with alacrity, soon we had one wrong righted—for the good of the victim and the misadventures of the villain” (11: 643–44). Over-sentimentality is the rule behind this mixed continuation, a style very common in Jane Austen fan fiction, which permeates most of the recent Sanditon novels, accounting for the loss of Austen’s satirical tone.

The only continuation that maintains both the depiction of Sir Edward as a silly man and Austen’s humorous tone is Carrie Bebris’s The Suspicion at Sanditon, the final book in a series, begun in 2004, in which Darcy and Elizabeth travel around England, meet characters from other Austen novels, and help them solve mysteries. In this case, the disappearance of Lady Denham before a dinner party to which they were invited again places Darcy in the role of the hero who will lead the investigation. In other words, even though Bebris is able to capture Austen’s satire, she still produces a story according to Pride and Prejudice fan fiction conventions. This conformity to convention and Bebris’s competence as a writer are perhaps responsible for the eighty percent of approval that The Suspicion at Sanditon registers at Amazon.com, and since this novel is the last in a series begun as a Pride and Prejudice fan fiction project, it’s safe to assume that most of these readers found Bebris’s continuation because of Pride and Prejudice rather than because of their interest in Sanditon.

Finally, the power of Pride and Prejudice can be felt even in Sanditon continuations that do not ostensibly intend to mix the two universes. In Juliette Shapiro’s completion, for instance, we can find many parallels between her characterization of Charlotte and Austen’s Elizabeth Bennet. For example, Charlotte refuses a proposal from Sidney Parker because she thinks he is mocking her, but when she learns the truth, she regrets it:

For want of a little less pride she might have responded differently. “I was prejudiced against him from the very start, his natural inclination to amuse and see the amusing was what I took to be his entire nature, she thought. Am I so blind? Can I have been so irrational as to think the jester his only role? . . . She had forfeited love for the sake of being forthright. From a fatuous determination to be willful, opinionated, and impenetrable came her loneliness and her complete despair. (127)

This moment of self-criticism is very similar to the one that Elizabeth undergoes after reading Darcy’s letter, when she discovers “that she had been blind, partial, prejudiced, absurd” (PP 230). And when Charlotte’s sister tries to cheer her up, she answers with another sentiment echoing Elizabeth: “You know I like to laugh whenever I can, but I confess that in this matter all humor is lost to me” (Shapiro 129). This tactic is not uncommon. Many authors of sequels and variations use not only Austen’s characters and plots but even her words to fill in the gaps of their new creations—sometimes as a clear homage to the author, sometimes as a clever wink at readers—but more often than not it is just plain copying.

This practice is even more evident in C. M. Mitchell’s series. As a Pride and Prejudice-Sanditon mixed continuation, these novels bring together, among many other characters, Darcy’s and Elizabeth’s families (even a Mrs. Bennet happily cured of her silliness), Charlotte Heywood’s family (including the majority of her thirteen siblings), and Jane and Cassandra Austen, who live in the neighborhood of Longbourn. Elizabeth is the narrator, but the plot that moves Mitchell’s five novels is the romance and courtship between various couples, mainly involving the Heywood sisters: Charlotte, Elizabeth, Marianne, Fanny, Emma, and Catherine. As their names indicate, they have the same personalities as Austen’s heroines, and they go through similar plots in order to achieve their happy endings. This series could as well have been named a combination of Sanditon and almost everything else Austen wrote.

Mitchell’s series is dependent on more than Austen’s novels. Elizabeth Heywood is not only very similar to her namesake but also appears in scenes clearly taken from the 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. In fact, this adaptation was essential to the rise of the current Austenmania and is still a reference point in the fanon. For example, there is a recurrence of the scene from the miniseries in which Elizabeth Bennet gets lost at Netherfield Park and finds Darcy playing billiards. In Mitchell’s novel Elizabeth “heard movement, and entered [the room], only to find Mr. Madison in it, by himself and playing at billiards. When he beheld her, he bowed. ‘Oh, forgive me,’ Eliza said, and then she turned around” (12: Kindle position 3351–54). There is also a scene in which Elizabeth Heywood plays with a dog just as in the BBC adaptation Darcy watches Elizabeth do the same: “The dog walked up to her, she patted its head and then it ran off. Spirited by the sight of it, Elizabeth ran after it and they raced down the lane next to the hill. . . . Eliza picked up a stick and began to play fetch with it” (12: Kindle position 3508–11). And, not surprisingly, there is a reimagining of the famous encounter between Elizabeth and Darcy after his emergence from the lake: “Elizabeth was looking around at the view of the woods when suddenly . . . Mr. Madison himself appeared, with his jacket off, his riding crop in his arms, his shirt sleeves rolled up and his vest unbuttoned” (12: Kindle position 3167–69). The intertextuality of current fan fiction goes beyond Austen’s novels to TV and movie adaptations.

Even Sanditon, with only eleven chapters, has a place in the Jane Austen fanon, although Marie Dobbs’s 1975 continuation becomes a major reference, especially when the original manuscript cannot act as an authority. Further, most recent continuations incorporate other aspects of the Austenmania, including sentimentality, the opposition between the perfect man and the bad villain (with Sir Edward alternating between these roles), and the influence of TV and film adaptations, usually the 1995 Pride and Prejudice. Jim Collins has argued that Austen fans not only produce stories; they are involved in a world building, a transauthorial, transmedial and transnarrative universe, and that “within this world building the relationship of the textual and the paratextual becomes increasingly hard to draw” (647). Since in these Sanditon continuations Austen’s satire is often discarded in favor of romance, it is fair to conclude that love is crucial to this world building, to how current fans read and understand Austen’s work.

NOTES

1See, for example, Darcy’s Story, by Jane Aylmer, published only a few months after the airing of the 1995 BBC version of Pride and Prejudice.

2For example, a search on Amazon.com (20 Oct. 2017) with the keywords “pride and prejudice variation” produced 1,441 stories, while the same search using the other novels’ titles didn’t even find ten results each.

3This series is a continuation of a previous one, with seven volumes based solely on Pride and Prejudice; therefore the volumes of this Pride and Prejudice-Sanditon mixed variation are numbered 8 to 12.

4Reviews posted on websites such as Amazon.com or Goodreads.com are interesting sources for readers’ reception to a novel, but it is impossible to determine whether the reviews posted constitute a relevant sample in relation to the total number of readers.

5Reviews available at https://www.amazon.com/Sanditon-Jane-Austens-Novel-Completed/dp/0684843420/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1508642157&sr=8-1&keywords=sanditon (accessed 20 Oct. 2017).

6My dissertation “Orgulho e Preconceito no Século XXI: A Austenmania e a Fantasia do Final Feliz” (Pride and Prejudice in the Twenty-first Century: Austenmania and the Fantasy of the Happy Ending”) focuses on these issues, but since it is written in Portuguese it will not be accessible to most readers. My essay in Persuasions On-Line 38.1, “Jane Austen, Heroine: Looking for Love,” builds on some of this material.

7See, for example, Rose Fairbanks’s No Cause to Repine (2015) and Deborah Ann Kauer’s Sense of Worth (2016).

8Reviews by CN (7 Feb. 2011) at https://www.amazon.com/Return-Sanditon-Anne-Toledo-ebook/product-reviews/B004LX0J1C/ref=cm_cr_getr_d_paging_btm_2?ie=UTF8&reviewerType=avp_only_reviews&sortBy=recent&pageNumber=2" (accessed 29 June 2017) and Marie Williams (26 May 2015) at https://www.amazon.com/Return-Sanditon-Anne-Toledo-ebook/product-reviews/B004LX0J1C/ref=cm_cr_getr_d_paging_btm_1?ie=UTF8&reviewerType=avp_only_reviews&sortBy=recent&pageNumber=1" (accessed 29 June 2017).

9Reviews available at https://www.amazon.com/Sanditon-Austens-Unfinished-Masterpiece-Completed/dp/156975621X/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1490473782&sr=8-2&keywords=juliette+shapiro (accessed 29 June 2017).

10Review entitled “A travesty”by MLW (9 Aug. 2011). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Sanditon-Austens-Unfinished-Masterpiece-Completed/dp/156975621X/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1490473782&sr=8-2&keywords=juliette+shapiro (accessed 29 June 2017).