Mr. Woodhouse boldly dissents from contemporary medical opinion when he asserts that “‘the sea is very rarely of use to any body. I am sure it almost killed me once’” (Emma 108). The extraordinary health-giving properties of the sea and sea air had long been medically endorsed when Jane Austen was writing in the 1810s. The publication in 1753 of Dr. Richard Russell’s A Dissertation Concerning the Use of Sea-Water in Diseases of the Glands had, despite its unpromising title, convinced the medical profession of sea water’s potentially therapeutic powers. Russell offered persuasive evidence from his personal practice near Brighton. Patients reported near-miraculous cures having bathed in or drunk sea water. Other physicians took note and made their own experiments and observations, reporting similar results. Thus began one of the great cultural phenomena of the Georgian period: the rise of the sea-bathing cure and, as a direct result, of the English seaside resort as a rival to inland mineral spas such as Bath and Bristol Hot-Wells. The fact that as late as 1817 in Sanditon Austen satirizes the craze for the creation of new resorts is evidence of the enduring faith in the sea’s therapeutic powers. So too does she show here that the extent of the curative powers of sea water and sea air continued to be warmly debated.

In Emma medical opinions about sea bathing are confined to the novel’s two hypochondriacs, Mr. Woodhouse and his older daughter, Isabella Knightley, and their offstage medical men, Mr. Perry and Mr. Wingfield. In contrast almost all of the characters in Sanditon hold strong opinions about the treatment of illness in general and in particular of the efficacy (or not) of the sea. This essay will explore what Sanditon reveals about what could be considered a healthy development: the democratization of medical knowledge. But Austen’s satire suggests that this development could have its dangers, as Akiko Takei has argued in her essay on lay medicine in Austen. We will consider in more detail Mr. Parker’s shameless claim that the sea and sea air at Sanditon are “anti-spasmodic, anti-pulmonary, anti-sceptic, anti-bilious and anti-rheumatic” (Later Manuscripts 148). As Austen was evidently deeply familiar with contemporary medical terminology, it is interesting that there is a striking absence of one widely used term. This essay will consider the fact that, despite the high profile in the period of “hypochondria” as a recognizable physical disease affecting the “hypochondres” or guts, Austen avoids using it.

Sanditon also has something significant to say about the medical profession’s loss of authority over its patients in an era of popular medical texts encouraging self-help. Mr. Parker’s conviction that an aspiring seaside resort must be in want of a physician is paradoxical evidence of this erosion of authority. Parker judges Sanditon to be thriving when visitor numbers increase and those famous signifiers of on-trendness, the blue shoe and the nankin boot, are seen on display in a shop window (160). Austen implies that Mr. Parker’s search for a medical man for Sanditon is on a par with this window dressing. A resident doctor would, he believes, “very materially promote the rise and prosperity of the place—would in fact tend to bring a prodigious influx” (147).

The origins of the sea-bathing cure: Dr. Richard Russell

From early in the eighteenth century, Georgian medicine had focused on the workings of the nervous system. Physicians pursued the notion that, by analogy with Newtonian physics, one underlying natural law would be discovered to govern all human physiology. Where the health-giving properties of mineral water had long been endorsed by the medical profession, it was Dr. Richard Russell’s 1753 dissertation on the use of sea water that seemed to suggest that the sea might very well be the long-sought cure-all. Interestingly, at a time when a successful medical man might have laid most emphasis on his well-to-do patients, Russell’s wealth of case histories concerned patients from all walks of life. He records treating farmers and their families, domestic servants, the captain of a ship (88), and even a thirteen-year-old Jamaican boy (122). Russell, who died in 1759, could not have foreseen that he would come to be seen as the originator of the fashion for sea-bathing. Indeed in 1861, the French historian Jules Michelet would go so far as to call him “the inventor of the sea” (Corbin 64).

Russell’s aims were more modest. He simply wanted doctors and their patients to explore this overlooked natural resource, one that was available to all. One particular thread of his thesis, however, became central to the development of seaside resorts as new sites of health and pleasure: his discussion of the healthiest places to bathe. The situation “should be clean and neat,” he writes, “at some distance from the opening of a river,” so that “the water may be as highly loaded with sea salt, and the other riches of the ocean, as possible” (379). Russell’s ideas are key to Mr. Parker’s claims for Sanditon:

“the finest, purest sea breeze on the coast—acknowledged to be so—excellent bathing—fine hard sand—deep water ten yards from the shore—no mud—no weeds—no slimy rocks—never was there a place more palpably designed by Nature for the resort of the invalid—the very spot which thousands seemed in need of—. . . ” (143)

Furthermore, it’s not like nasty Brinshore, the “‘paltry hamlet’” that lies “‘between a stagnant marsh, a bleak moor and the constant effluvia of a ridge of putrifying sea weed’” (143).

But Russell was not claiming the sort of originality that would subsequently be attributed to him. His statement that the ideal seashore should be “sandy and flat; for the conveniency of going into the sea in a bathing chariot” (380) shows that the craze for sea-bathing predates him. Bathing chariots—bathing machines—are thought to have first appeared at Scarborough on the northeast coast of England in the 1730s.

As well as giving convincing evidence of the therapeutic properties of sea water, Russell offered detailed advice on how to undertake a sea-bathing cure. Other medical writers would follow suit. It was Russell who isolated the important features, doubtless modelling them on the protocols of the mineral-water cure. Key were appropriate diet, the quantities of seawater to be ingested, and the time and length of the “dip.” The notion of applying seawater internally as well as externally is unsurprising when we consider the practice of drinking often foul-smelling mineral waters at spas.

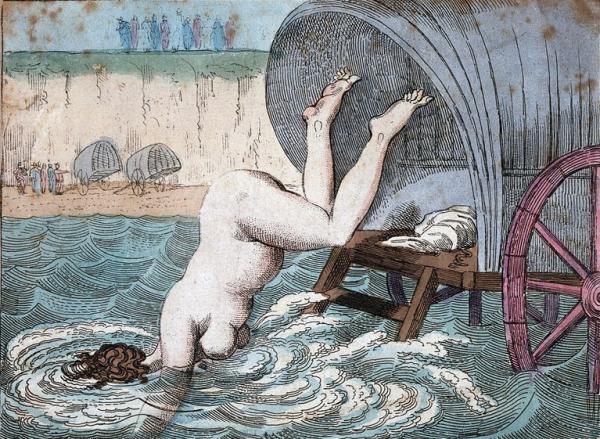

Venus’s bathing. (Margate). A fashionable dip.

Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Again it is unsurprising that in advocating sea bathing for a large range of diseases, Russell expresses caution about attempting it without professional medical advice. Only a doctor has the skill to recommend in each case “how long the patient should remain” in the water, “what is to be done at his coming out,” and “at what time of the day he should enter it” (381).

“The whole medical tribe”: The evolution of medical ideas about the sea

A significant number of medical texts on the benefits of sea bathing followed in Russell’s wake. But where Russell’s writing was addressed purely to other medical professionals (the first edition of the essay was written in Latin, the standard language of medical writing), subsequent writers addressed the general public. This democratization of medical knowledge was not, for the most part, ideologically driven. Doctors writing after Russell reveal a new anxiety about their fees and, more fundamentally, their medical authority. Both were threatened once patients willfully self-medicated by taking up sea bathing without seeking medical advice. Text after text underlines the dangers to those who naively attempt a sea-cure without proper professional supervision.

So, for example, some twenty years after Russell, Dr. Robert White in The Use and Abuse of Sea Water Impartially Considered (1775) is indignant about this sort of usurpation of medical authority. White identifies

the propensity which people of all ranks have discovered towards Sea bathing. Whatever the complaint is, whether Chronic or Acute, the patients promise themselves relief. . . . [T]he Patient unwarily sports with danger; suspects no evil to arise from the use of so general and popular a Medicine; seldom consults those, who from their observations and practice are best able to judge of the propriety of its use. (3–4)

To reinforce the necessity of professional advice on the subject, he lists a number of “Cautions” (7). These include sticking to one dip (“the sooner the business is over the better”); bathing only at the proper times (ideally “a little before noon”), and for the proper length of time (“No-one should continue above a minute in the water, medicinally”). “Excess of bathing” occasions “relaxations, spasms, and many other disorders” (10). Patients who ignore White’s advice usually end up dead.

Some subsequent medical writing is nakedly opportunistic. In the Wellcome Library’s collection of Rare Materials in London there is a tiny, cheap-looking pamphlet published in 1798 by a Dr. Squirrell, entitled Maxims of Health. This pamphlet additionally offers Remarks on Sea and Cold Bathing. The Effects of Sea Air &c. The author is another who insists that sea bathing “when improperly applied” (28) can be dangerous. He threatens readers that such unsupervised activity can have disastrous effects on the very complaints it was supposed to treat and could thus “render them for ever incurable.” For good measure, he rants at those “persons [who] imagine themselves qualified to judge, and boldly venture of their opinion, of the propriety of Bathing, who have not the smallest acquaintance with anatomy, physiology, the history of diseases, the science of medicine, or philosophy in general” (29). In other words, woe betide presumptuous amateurs.

What Squirrell particularly recommends for those bent on taking to the sea is “a proper dose of Tonic Powders” beforehand. At the back of this booklet is an advertisement for just such tonic powders, prepared by Dr. Squirrell himself. These can be purchased either in packets (at 2s.9d.) or as tonic drops (at 5s.5d.). Such quack medicines were evidently big business. In Sanditon, Mrs. Griffiths “did never deviate from the strict medicinal page,” except “in favour of some tonic pills, which a cousin of her own had a property in” (203). Neither Mrs. Griffiths’s cousin nor Dr. Squirrell, however, would get business from Sanditon’s self-reliant Diana Parker, who insists, “‘My appetite is very much mended I assure you lately. I have been taking some bitters of my own decocting, which have done wonders’” (191).

But among serious physicians, there was a new spirit of humanitarianism. An idealistic Quaker physician, John Coakley Lettsom, in his essay “Hints for Establishing an Infirmary for Sea-Bathing for the Poor of London,” argued that scrophulous (tubercular) diseases were particularly prevalent among poor children. Such diseases required sea air and sea bathing: remedies that “might be procured with the smallest possible expense” (246). By 1791, despite a certain amount of nimbyism from local residents, the General Sea-Bathing Infirmary at Margate (soon to become the Royal Sea-Bathing Infirmary) was successfully set up.

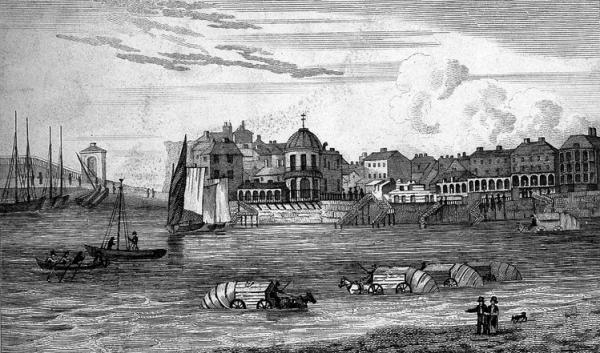

The Back of Bathing Houses, Margate

Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

One of the first physicians at the infirmary was John Anderson. His pamphlet A Practical Essay on the Good and Bad Effects of Sea-Water and Sea-Bathing gives us much more nitty-gritty detail than previous publications about how the now widespread bathing industry was operating at shore-level, as it were. He includes medical evidence from practitioners working in the main Kentish resorts of Thanet, Broadstairs, Dover, and Ramsgate. Anderson is sympathetic to the new bather who is fearful. Unlike Lettsom, who inveighed against the dangers of alcohol, Anderson recommends “timid persons” to take “a glass or two of generous cordial wine” on entering and indeed on coming out of the water. He tells them to “shut their ears, eyes, and mouth,” trust “their sagacious, faithful guides,” and “all will be well” (3).

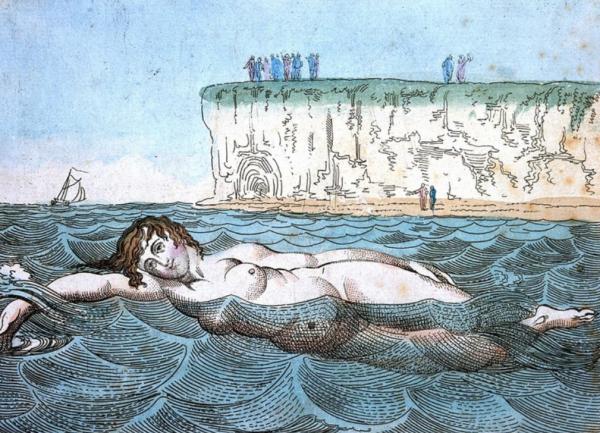

Venus’s bathing. (Margate). Side way or any way.

Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

But Anderson himself is not above recording a few of his own miraculous cures. A female patient, “who had been six years in the East Indies with a first husband, and after bearing nine children to him and a second husband” (16), consults him after a succession of failed sea-bathing cures in Margate, which seemed to worsen her symptoms. He discovers her previous physician had insisted on a “low water-gruel and vegetable diet” and not even “a glass of cordial wine, or anything comfortable” (16). Anderson prescribes a diet of shellfish, meat, and “a few glasses of generous red port after dinner.” The result is dramatic: “in seven days she had not a morbid symptom. She got on horseback, and rode repeatedly about the island” (18). One of his experienced male bathing guides in Margate, Zechariah Brazier, tells him about a Mr. Sanguinetta, who twenty-five years ago had “universal palsy”—“all below his head was without sensation or motion” (32). Brazier, assisted by his wife and three men, used to carry him into a bathing machine for regular dips in the sea. This result was a complete cure: “he threw away his second crutch, and walked with a cane, took up his German flute and played.” Subsequently his wife bore him seven children (33–34).

The Austens at the seaside

What would Jane Austen herself have known about these competing claims about the power of sea bathing? We know that her racy cousin, Eliza de Feuillide, took her young son to Margate for a cure from December 1790 through January 1791 on medical advice, her physician having told her that “one month’s bathing at this time of the Year was more efficacious than six at any other” (Le Faye 97). Despite her description of the severity of the weather conditions, the cure seems to have been effective: “The Sea has strengthened him wonderfully & I think has likewise been of great service to myself, I still continue bathing notwithstanding the severity of the Weather & Frost & Snow which is I think somewhat courageous” (99) It is evident from Feuillide’s endorsement that as late as the early 1790s doctors were continuing to prescribe the winter sea-bathing cure.

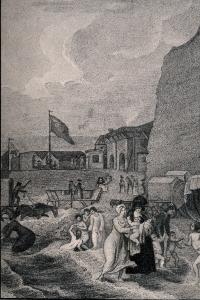

Ramsgate:

The Bathing Place 1788

Courtesy Wellcome Collection

But the tide was turning. When we get a rare glimpse of Jane Austen at the seaside in September in 1804, it is evident that, far from seeking a cure, she was simply enjoying herself. She writes to Cassandra from Lyme Regis about bathing with her maid Molly: “The Bathing was so delightful this morning & Molly so pressing with me to enjoy myself that I believe I staid in rather too long, as since the middle of the day, I have felt unreasonably tired” (14 September 1804). There is no talk here of sea bathing for health, nor indeed will Austen seek a cure in the next decade when symptoms of her illness begin to appear. Unlike Eliza, for Austen and her extended family the seaside mainly offered pleasure. We know that what sweetened the blow of her parents’ sudden decision to move to Bath was the plan to travel: “the prospect of spending future summers by the Sea or in Wales is very delightful,” she wrote (3–5 January 1801). We subsequently hear of their staying in various seaside resorts, and refusing an invitation to spend a summer in Shropshire, Austen privately telling Cassandra, “for the present we greatly prefer the sea to all our relations” (25 January 1801). But she was a discerning visitor. Not all seaside resorts were the same. On one occasion she mentions an acquaintance who “talks of fixing at Ramsgate.” “Bad Taste!” she remarks, adding, “He is very fond of the Sea however;—some Taste in that—& some Judgement too in fixing on Ramsgate, as being by the Sea” (14–15 October 1813).

In Sanditon, when we hear of the dashing Sidney, “‘with his neat equipage and fashionable air’” (159), he has apparently abandoned his “‘scheme to the Isle of Wight’” (164). We can be sure that Sidney’s projected trip to the fashionable Isle of Wight was solely in pursuit of pleasure, as was Frank Churchill’s to Weymouth.

Does the sea-bathing cure become redundant?

There is a subtle shift in claims for the efficacy of the sea-bathing cure in the new century. Altogether the emphasis moves from medically approved dips to more general endorsements of the seaside and to the enlivening atmosphere of the resort. In particular it is sea air as opposed to seawater that is increasingly cited as health giving. Although Diana Parker in Sanditon asserts “‘in my present state, the sea air would probably be the death of me’” (163), her brother, Mr. Parker, believes that even his sprained ankle will respond to “‘[a] little of our own bracing sea air’” (141).

By 1807, when Dr. Thomas Trotter publishes his important intervention, A View of the Nervous Temperament, it is clear that the medical establishment is now being called to account. Trotter dismisses the spate of medical publications on the sea-bathing cure, which, he points out, are mostly cynical attempts to get patients to purchase the so-called tonics dispensed by the book’s author. Trotter is particularly scathing about the more preposterous claims some modern physicians continue to make for the necessity of seeking medical advice before bathing. These, Trotter writes, are simply “greedy attempts to bring it under their control” (265–66). He then makes the wonderfully common-sense observation: “Leaving all these gentlemen in full possession of their theories, I must beg to consider it [sea bathing] principally as an exercise and amusement” (266). Trotter does recommend seaside watering places as “highly beneficial to nervous people,” who will benefit by “shaking off indolent customs, and forcing themselves into company and cheerful society” (268).

“Nervous people” were thought to be particularly prone to a condition which was of central importance to Georgian medicine: hypochondria. It is a curious term for us because its modern usage is so far removed from its historic one. In its dominant eighteenth-century sense, hypochondria was a recognizable disease, located in a sufferer’s hypochondres, the lower abdomen. Its chief symptoms were digestive disorders, but it was usually attended by melancholy or depression: “a languor, a listlessness, or want of resolution and activity with respect to all undertakings; a disposition to seriousness, sadness and timidity,” as the influential professor of medicine, William Cullen, described it in 1777 in First Lines of the Practice of Physic (3: 249). Roy Porter, in his introduction to his edition of George Cheyne’s The English Malady (1733), has shown how well-to-do patients could be proud to proclaim they were suffering from hypochondria, as it was believed to afflict only the elite of society. Developments in the medical understanding of the nervous system allowed the educated public to view their tendency to melancholy as a direct result of their especially refined nerves. Cheyne offered a reassuring analysis: the combination of refined nerves and a lifestyle of unimaginable luxury—rich foods and wine, being carried from one site of pleasure to another in sedan chairs—meant hypochondria was the preserve of society’s elite.

Cheyne insisted that melancholy or hypochondria (almost synonymous terms) was a recognizable physical disease and, importantly, quite separate from madness. William Cullen, however, understood hypochondria to be “idiopathic” (3: 219)—the medical term which basically means “we don’t know.” Importantly, Cullen identified hypochondria as a disorder of the mind rather than the body, describing sufferers as

particularly attentive to the state of their own health, to even the smallest change of feelings in their bodies, and from any unusual feeling, perhaps of the slightest kind, they apprehend great danger, and even death itself. In respect to all these feelings of observation, there is commonly the most obstinate belief and persuasion. (3: 250)

Thus although hypochondria mainly referred to an actual illness, its secondary meaning—in the Parker family sense—was clearly there in 1777.

Sanditon and the sea-bathing cure

In Sanditon, Jane Austen gives the same robust commonsense as Trotter to Charlotte, who, hearing the tribulations of the Parker siblings, suspects “a good deal of fancy in such an extraordinary state of health” (192). Observing Miss Parker’s constant use of salts and drops, she thinks there are no symptoms which would not respond simply to “putting out the fire, opening the window, and disposing of the drops and the salts” (193). To Arthur’s self-diagnosis she speaks out:

“As far as I can understand what nervous complaints are, I have a great idea of the efficacy of air and exercise for them,—daily, regular exercise;—and I should recommend rather more of it to you than I suspect you are in the habit of taking.—” (196)

It is clear which side of the debate Jane Austen is on.

Chamber Horse

Lady Denham is equally forthright but her target is the medical profession. A doctor at Sanditon would, she believes, “‘be only encouraging our servants and the poor to fancy themselves ill’” (171), and she blames the death of her second husband, Sir Harry, on a physician’s expensive interventions. At seventy, Lady Denham has never consulted one, nor taken physic “‘above twice.’” Commercially savvy, however, she keeps “‘milch asses,’” recommending their milk to sufferers of consumption (171). Asses’ milk is so ancient a remedy that eighteenth-century medical texts rarely allude to it (although Russell says he resorts to “a Warm Bathing, and Asses Milk” when diseases have not been responsive to “the Power of Sea-Water”) [158]. Another good, old-fashioned preventative Lady Denham recommends is the chamber horse. These were not, disappointingly, adult-sized rocking horses but well-upholstered chairs with powerful springs which allowed the occupant to bounce up and down. Dr. George Cheyne had been advocating its use for winter exercise since at least 1740, when he recommended one to Samuel Richardson (Guerrini 163). Cheyne had long argued for the importance of exercise, explaining in The English Malady that riding in particular was effective for allowing the “alimentary instruments and Hypochondries” to be “most shaken and exercised” (180). According to Lady Denham, she can easily supply one “‘at a fair rate—(poor Mr. Hollis’s chamber horse, as good as new)’” (171). Austen drily suggests the item in question did its owner no good. Poor Mr Hollis, we must assume, is dead.

Unlike the healthy Lady Denham, however, the Parker siblings have an obsessive interest in their health. Aside from Mr. Woodhouse, they are Austen’s most colorful hypochondriacs. But, as we have noted, it is curious that in 1817 Jane Austen does not use the term. Yet Diana, Susan, and Arthur Parker fit the bill precisely. As William Cullen wrote, “It is said to be the manner of hypochondriacs to change often their physician” (3: 266). Indeed the Parkers, having consulted “‘physician after physician in vain,’” have “‘entirely done with the whole medical tribe’” (163).

Jane Austen clearly understood the ludicrous claims of hypochondriacs—from Mr. Woodhouse’s obsessive fears of wedding cake and slight breezes to the Parkers’ florid array of personalized symptoms. Arthur Parker’s conviction that without butter, dry toast is “‘far from . . . being wholesome’” (198) recalls Mr. Woodhouse’s well-known advocacy of boiled eggs. But Arthur’s conviction that toast “‘hurts the coats of the stomach’” suggests, in his knowledge of basic anatomy, that he has more access to popular medical texts than does Mr. Woodhouse. I want to restate the important point that although Jane Austen evidently knew a hypochondriac when she saw one, she does not use either the term itself or its cognates. Yet the word itself in 1817 continued to be used as a valid medical term denoting a disease of the digestive system—not, as we would understand it, a neurotic fretfulness about one’s health.

It is interesting therefore that in Mr. Parker’s extensive and eccentric lexicon, hypochondria makes no appearance, when we might expect it in his list of the sea’s miraculous properties (“anti-spasmodic, anti-pulmonary, anti-sceptic, anti-bilious and anti-rheumatic” [148]). Let us consider this now in detail.

He held it as certain, that no person could be really well . . . without spending at least six weeks by the sea every year.—The sea air and sea bathing together were nearly infallible, one or the other of them being a match for every disorder, of the stomach, the lungs or the blood; they were anti-spasmodic, anti-pulmonary, anti-sceptic, anti-bilious and anti-rheumatic. Nobody could catch cold by the sea, nobody wanted appetite by the sea, nobody wanted spirits, nobody wanted strength.— (148)

“Anti-spasmodic” was a conventional medical term. Quincey’s Lexicon-Medicum of 1817 defines “spasmodic” as “the power of allaying, or in removing inordinate motions in the system” (58). It covers anything from diarrhea to epileptic fits. Effective antispasmodic remedies, according to Cullen, included assafoetida, castor oil, and musk.

The term “antiseptic” appears occasionally in medical texts. But “anti-pulmonary,” “anti-bilious,” and “anti-rheumatic” are Mr. Parker’s own invention. (Indeed the Oxford English Dictionary’s first sighting of “anti-bilious” is in Sanditon). It is noteworthy that he could, but doesn’t, make a claim for the sea’s being “anti-hypochondriacal.”

And what about Mr. Parker’s claims that sea air and sea bathing were “healing, softing, relaxing—fortifying and bracing—seemingly just as was wanted—sometimes one, sometimes the other” (148–49)? The valences of words are interesting. Where we’ve seen “hypochondria” becoming a pejorative term, “relaxing” will go in the opposite direction over time. To have physiologically “relaxed” nerves in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was to have nerves lacking in power, dangerously unresponsive to the all-important effects of irritability and sensibility. But by including “relaxing” in his list of beneficial qualities of the seaside, Mr. Parker appears to be drawing on a new understanding of the word that was only just coming into use. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the sense of “relaxed” as “free from anxiety” first appears in 1773; its second quoted use is from Lady Morgan’s The Wild Irish Girl (1806), a novel with which Austen was familiar.

When Charlotte first meets Susan Parker, however, she observes that in comparison with her sister Diana, she is “more thin and worn by illness and medicine, more relaxed in air, and more subdued in voice” (193)—her “relaxed” air implying weakness and languor. In cases of miscarriage, Thomas Trotter wrote, ninety cases out of a hundred “may be imputed to a relaxed nervous frame” (36). What Mr. Parker’s use of “relaxing” therefore suggests is that he is freely appropriating medical terms to suit his own needs without a clear sense of their meaning. This would fit with what Akiko Takei has shown about the concerns of medical men during the period with the dangers of loose usage of medical terminology. Takei quotes, for example, from James Makittrick Adair’s Medical Cautions (1786): “Names or terms, when improperly employed in matters of science, necessarily create confusion and error.”

What is particularly significant about Austen’s presentation of hypochondria in our sense is that the three adult Parkers who enjoy the status if not the title of hypochondriacs do not suffer from hypochondria’s concomitant melancholy. They’re not the first hypochondriacs to fret about symptoms while being evidently in robust health. They are perhaps descendants of Moliere’s La Malade Imaginaire, first translated into English as “The Hypochondriac” by John Ozell in 1714. But where Mr. Woodhouse and his daughter Isabella clearly share a nervous temperament and suffer chronically from anxiety, the Parkers seem worryingly well, Diana, in particular, tirelessly ready to interfere in the lives of others.

We will never know whether a newly mentioned character, the sickly heiress Miss Lambe is a genuine invalid or a hypochondriac in either sense of the word. All we can say for sure is that she, poor thing, is obliged to undergo the full medically supervised sea-bathing cure, including being dipped from a bathing machine.

A final unknown is where Jane Austen found the medical language she gleefully supplies for Mr. Parker. There is a high likelihood that her family would have had a copy of William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine, an immensely popular book, regularly reprinted. From 1803 onwards it included an additional essay about sea bathing. She may well have had access to some of the many medical books on sea bathing that appeared in the early nineteenth century, such as Practical Observations Concerning Sea Bathing (1804) by Alexander Buchan, William Buchan’s son.

We can only speculate on the reason Jane Austen refused to use the term hypochondria. Perhaps it was out of tact: her mother’s tendency to fret over her health is well documented. What we know for certain is that Austen rarely spoke of her own illnesses. When towards the end she did mention her own symptoms, she reckoned what she was suffering from was biliousness. It is a sad irony—probably a deliberate one—that one of her arch hypochondriacs, Diana, suffers from attacks of her “‘old grievance’”: “‘spasmodic bile’” (163). And that it’s the one condition Arthur is sure he is not suffering from: “‘If I were bilious,’” he continued, “‘you know wine would disagree with me, but it always does me good.—The more wine I drink (in moderation) the better I am’” (196). Beneath the broad comedy of Sanditon, Austen has explored the limitations of contemporary medicine. But on the other hand, we know Austen’s fondness for a glass of wine. Perhaps there she is having the last laugh.