Arguably, the teenage Jane Austen’s two favorite words are “Author” and “Finis.” With few exceptions, she writes them boldly above and below each of the capsule novels and plays with which she filled three manuscript notebooks between the ages of eleven and seventeen: “Finis” 16 times to “Author” 20 times. Together, “Author” and “Finis” imply supreme confidence: the confidence to take control and impose an outcome; to own up to a story and to possess it completely. Everything is on show in these early works: from the starved cartoon characters to the hectic inconsequentiality of their madcap adventures. Self-division, moral and psychological relativity, narrative indirection—all those complicating, delaying strategies we associate with the developed novel—belong elsewhere and much later. Here, by contrast, everything is brightly lit and simple. The path from “Author” to “Finis” is swift and straight. Simple, too, is the fraudulence and fakery of it all; for the best joke is that Austen is not so much authoring and finishing as hoaxing and finishing off.

The young Jane Austen was a looter and a ruinist; a literary tourist, she revisited her voracious reading in acts of wilful, comic misappropriation, reducing her favorite texts to rubble in order to examine their various parts and see how they work. Do characters in fiction need to be believable? Do actions need motives? Must a named hero appear in his own story? What does it mean for a dedication to be longer than the tale that follows? How spare, elliptical, and empty can story be and still be comprehensible? Projecting herself into classic and pulp fiction alike, the young Austen constructed little dwellings among the ruins she made from her favorites in the service of her own fledgling aesthetic—from the novels of Richardson and Fielding, from the moralizing essays of Samuel Johnson, from sentimental romances and schoolroom textbooks.

The actors in the teenage writings are violent, narcissistic, exuberant marauders, given to theft, brawling, murder, and sexual misdemeanour; not so different, then, from that arch-ruinist King Henry VIII, described by the “partial, prejudiced, & ignorant Historian” of “The History of England” as one who has been, through “his abolishing Religious Houses & leaving them to the ruinous depredations of time . . . of infinite use to the landscape of England in general” (Teenage Writings 120, 126–27). The fifteen-year-old Austen’s presentation of the rapacious Tudor tyrant as, like her Gothic self, an admirer of ruins in a landscape, is lifted directly from an acknowledged favorite writer, William Gilpin, who, in comparing Henry’s suppression of monastic foundations with Oliver Cromwell’s destruction of castles a century later, described both as “masters” in a style of “composing.” “Certain however it is,” Gilpin concluded, “that no man, since Henry the eighth, has contributed more to adorn this country with picturesque ruins” (Observations 2: 122).1

The Abbey School, Reading, where Austen was sent to board aged nine, was housed in a thirteenth-century gatehouse and adjoining building overlooking the ruins of Reading Abbey, whose physical destruction was the work of Protector Somerset in the reign of Henry’s son, the minor Edward VI. The earliest of the teenage stories may well have been incubated at school where, as she later reminded her sister and fellow-boarder, they could have died laughing (1 September 1796).

“Detached peices,” “Scraps,” “Morsels,” and assorted, truncated tales litter the teenage notebooks, among them, the two novellas that make up Volume the Third, appropriated and revised many years later by the next generation of scribbling teenage Austens. The built ruin and the crumbling edifice provide architectural equivalents for these “unfinished performances,” as the young Austen proudly calls them (TW 1, 63, 67, 34). In “Ode to Pity,” the poem dedicated to Cassandra Austen that closes Volume the First, an “Abbey,” “a mouldering heap” (66) borrows its gothic decay from Gray’s “Elegy”: “Where heaves the turf in many a mouldering heap” (l. 14). Volume the Second houses the “dismal old weather-beaten” Lesley Castle with “its dungeon-like form” (107). In the unfinished story “Evelyn” in Volume the Third, Frederic Gower is reduced to temporary madness by the terror-inducing “Gloomy Castle blackened by the deep shade of Walnuts and Pines,” home of his dead sister’s dead fiancé (168). Of course, much of this is a teenage girl’s delighted spoofing of the sensation fiction she avidly devoured: later, her over-imaginative teen heroines, Marianne Dashwood, Catherine Morland, and Fanny Price, will all thrill to the romance of ruins.

Destruction breeds appreciation. “A piece of Palladian architecture may be elegant in the last degree,” wrote Gilpin:

The proportion of it’s parts—the propriety of it’s ornaments—and the symmetry of the whole, may be highly pleasing. But . . . should we wish to give it picturesque beauty, we must use the mallet . . . we must beat down one half of it, deface the other, and throw the mutilated members around in heaps. In short, from a smooth building we must turn it into a rough ruin. No painter, who had the choice of the two objects, would hesitate a moment. (Three Essays 7–8)

The Picturesque is a persistent element within English taste; the violent origins of its pleasing decay acknowledged from Gilpin and Austen through to the Blitz aesthetic of Kenneth Clark and John Piper and the more recent ruin lust captured in the film installations and photographs of Jane and Louise Wilson.2 In ruins we commune with an imagined past; we create new forms among their broken vistas; ruins encourage reflection, dialogue, and invention.

Cool, ironic, and merciless, the young Austen understood the comic and didactic potential of ruins. When she began writing, around the age of eleven, the novel was still new enough, novel enough, to provide the occasion for dissertations on its origin, purpose, seriousness, and danger. Her apprenticeship was spent ripping novels apart and from their ruins creating modern follies of her own, compressed edifices of fractured and colliding perspectives whose fragmentary structures witness the excitement she felt for the form. As the late-assembled “Opinions” of Mansfield Park and Emma and “Plan of a Novel” attest, she would never abandon the habit of dispassionately inspecting the dismembered blocks of her own fiction.

But something more is going on and continues to go on to the very end of her writing life: the adult Austen’s brilliantly thrifty, condensed style and its attendant critical consciousness operate perilously close to fragmentation. Consider the evidence: six finished novels, three of which were recast or “lopt & cropt” (29 January 1813) over considerable gaps of time; one other has two endings, neither of which we can surmise was integral to its conception; then, there are two abandoned draft novels, The Watsons and Sanditon, and a discontinued short novel in letters, Lady Susan, with an abruptly patched ending. This is a high count in such a slim body of work. If she honed her art among ruins, Austen continued by building fragments.

![]()

Ruins are temporal constructs; fragments are spatial. The blotted and reworked page of the draft manuscript displays characteristics of both. Both are, of course, metaphors for the Romantic imagination’s work of creation through recovery and by organizing parts into wholes, regularly described in topographical and architectural terms. Wordsworth’s famous trope of the “gothic church,” in which The Prelude serves as “ante-chapel” to the main body of The Recluse, while his “minor Pieces . . . when they shall be properly arranged,” may be “likened to the little cells, oratories, and sepulchral recesses, ordinarily included in those edifices” (171). The reader is invited into a series of connecting spaces, by preference moving through them in a determined temporal sequence. This statement of intention appeared in the preface to The Excursion in 1814, when Wordsworth was forty-four.

By contrast, Keats’s cruelly curtailed life and work, over age twenty-five, are presented apologetically by his nineteenth-century biographer, Richard Monckton Milnes, as no more than a “fragment,” albeit one whose “singularity and greatness” justifies the attempt “to draw general attention to its shape and substance.” Milnes’s model for the poet’s life, as it was Keats’s inspiration, is the Classical statue, the broken survivor from a distant past whose fragment status proves culturally empowering, intimating perfection withheld rather than inconceivable—and so, for Milnes, confirming Keats’s advancement to the pantheon of great literature: “Truncated as is this intellectual life, it is still a substantive whole, and the complete statue, of which such a fragment is revealed to us, stands perhaps solely in the temple of the imagination” (1: 2; 2: 105).3 The affective appeal of a sleight of thinking that confounds modern longing in ancient loss is exposed in the famous aphorism of the Romantic fragment philosopher Schlegel: “Many works of the ancients have become fragments. Many works of the moderns are fragments at the time of their origin” (134).

Austen’s organizing trope is the English village, as she remarks in two of her letters: “You are now collecting your People delightfully, getting them exactly into such a spot as is the delight of my life;—3 or 4 Families in a Country Village is the very thing to work on—& I hope you will write a great deal more, & make full use of them while they are so very favourably arranged” (9 September 1814); and “such pictures of domestic Life in Country Villages as I deal in” (1 April 1816). With its great house, its church, perhaps a shop, an inn, even a militia encampment (for we know from Pride and Prejudice that by 1813 the south of England resembled a military camp), and an assortment of gentry families and carefully culled professionals, Austen’s village is a bustling place. It has been culturally ingested over the last two hundred years, from Tunbridge Wells to Texas, from Cheltenham to China, as a vision of England—England as immemorial village, assembled in parts, and over time, examined from different angles from novel to novel but solid and enduring, until abandoned for the new-built houses, set apart from the “real village of Sanditon” (Minor Works 382) and marching perilously close to the edge of a cliff. Austen’s fragmentary art is remarkably cohesive; its pieces lock together with the satisfying click of a jigsaw puzzle.

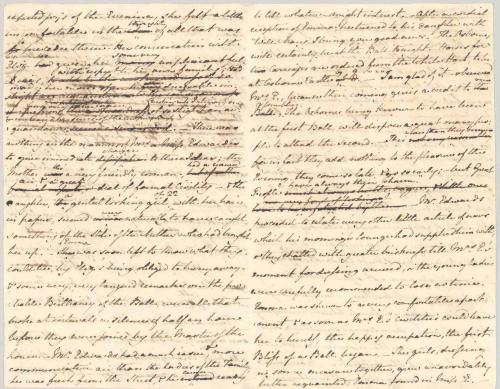

“Remember,” warned Coleridge, the great strategist of the fragment, “that there is a difference between form as proceeding, and shape as superinduced;—the latter is either the death or the imprisonment of the thing;—the former is its self-witnessing and self-effected sphere of agency” (2: 262). The high incidence of both fragmentation and cohesion (cohesion in and across fragments) in Austen’s work suggests that she shared with the great Romantic poets an understanding of “form as proceeding” and an affinity for open-ended structures. The overwhelming evidence for habits of spontaneous composition exhibited in her draft fiction manuscripts would support this view; in drafts the deployment of graphic space clarifies the act of writing. It is Austen’s habit to leave no constant margins, no active space from which to re-enter or critically survey her writing. Most writers do leave margins, whether this space is a regularly defined sector of each page—a wide left-hand margin (as in the case of William Godwin and Mary Shelley) or the bottom of the page or the reverse of the previous leaf, functioning, as it does for Walter Scott, as an enormous left-hand margin. By contrast, Austen’s draft page is saturated with the primary act of writing; she anticipates no return.

Figure 1: The Watsons b2: 4-5, showing how densely Austen filled her page

(Click here to see a larger version.)

In general, draft manuscripts are fluid: the page is not only a space for writing but also, and unlike the printed page, a site of temporal succession, of demolition and repair, where we see the stages of composition through which writing emerges and builds on itself. The observable pattern in Austen’s draft manuscripts of relatively clean passages, free from correction, broken by densely rewritten sections, suggests not only a preference for vocal or phonocentric development—that some compositional acts (the capturing of speech and recording of conversation, for example) took shape in her head prior to writing and following the dictates of an inner ear—but also that, as a writer, Austen was process-centered rather than programmatic. That is, she wrote spontaneously or immanently, with limited reliance on advance planning; and even though writing evolves fragmentarily, these fragments are more fully textualized from the outset, growing from within the space they occupy through layers of rewriting (Sutherland 127–28).

This kind of rewriting, from inside the process of composition, is different from the return of the revising hand to update a detail, refine a phrase, or refresh the currency of a story after it is finished. Of course, novels, unlike short lyric poems, are not likely to take shape simply from the accumulation of local passages of spontaneous writing and sound transcription, without anticipation of structure or larger conceptualization. There must also be planning, on large and small scale. What is observable from Austen’s surviving manuscripts is a persistent tendency rather than a total explanation for the way she worked.

At the same time as working processively, or immanently, Austen was keenly aware of the novelist’s duty to impose order, to resolve the problem at hand. The finished structures of her printed novels bear witness that her moral judgments can be harsh, abrupt, and final. There is a degree of sacrifice, of waste, which is (to return to Coleridge) the consequence of shape “superinduced.” Her best heroines, whose eyes and ears and developing consciousness are also ours, are organic creatures, seemingly capable of life outside the novel, but other characters (Maria Bertram and Jane Fairfax, for example) are briskly cast aside and silenced at the end. Perhaps this “proceeding” way explains her search for images of Mrs. Bingley and Mrs. Darcy among the collection of portraits on show in Spring Gardens, London, in May 1813, and her habit of sharing details of the activities of some of her characters beyond the limits of their novels (24 May 1813; Austen-Leigh, Memoir [2002] 119). Austen’s endings are where the tension between the processive and the super-induced is most keenly felt; endings are not where she appears to best advantage as a writer. By contrast, it might be argued that her fragments retain in their openness a kind of honesty.

![]()

The fragment is key to understanding Austen’s art, which is built upon ruin, recycling, and waste. She began as a ruinist; she continued as a recycler (recycling being the regular fate of ruins). Austen is an inveterate and accomplished recycler—of stories, themes, and the most minor details. She is a writer whose material waited, as she herself said, “upon the Shelve” (13 March 1817), in some instances, for years. The way she patches and fills her small manuscript pages provides an emblem of her processive imagination as she crosses and re-crosses her little plot of fictional ground to bring one novel out of another. The method contributes powerfully to our sense of familiarity with her world.

At the local level, Austen writes thriftily, with composition emerging through repetition. “Amiable,” “agreable,” “disagreable” are favored adjectives; she works them hard, feeling no compulsion to vary. Revision, too, is often a matter of repetition, a word set down and deleted, another tested in its place, only for the original to be restored: “Postboy” > “Driver”> “Post-Boy” (Fiction Manuscripts, The Watsons b8: 5; MW 349); “thought” > “found” > “thought” (FM, Sanditon b3: 17; MW 416). She hoards and reuses phrases—so much so, that groupings of words regularly strike the ear as half-echoes: the “‘old Coachman,’” who “‘will look as black as his Horses’” in The Watsons (b6: 3; MW 340), is recalled in the opening page of Sanditon, where the driver is described as “looking so black, & pitying & cutting his Horses” (subsequently deleted). Elizabeth Watson, observing of her sister Emma, “‘You are like nobody else in the world’” (b6: 8; MW 342), brings to mind Fanny Price’s self-description: “‘I am unlike other people I dare say’” (MP 197).

Recycling is not always so effective: in Sanditon it is likely that Heywood is struck upon as the uninspired family name of Charlotte Heywood because her father, Mr. Heywood, is introduced in “a Hay field” “among his Haymakers” only lines after Mr. Parker has noticed a cottage, “situated among wood” (b1: 3; MW 364–65). In the fragment’s final pages, Austen probably struck upon and subsequently struck out a reference to “Hollies” (“clusters of fine Elms, or rows of old Thorns & Hollies” [b3: 37; MW 426]) because of its proximity to “poor Mr Hollis,” only two pages later (b3: 39; MW 427). D. A. Miller, that shrewd celebrant and castigant of Austen’s style, has called this “undisciplined . . . associationism” (87); it is the downside of a recycling way of writing, where self-sprung linguistic traps topple literary verisimilitude into bathos, finely honed style into ruin.

What exactly is The Watsons? Is it the fragment of an abandoned novel? We assume so, and that Austen, emboldened by the sale of “Susan” to Crosby & Co. in 1803, began it in an attempt to assert through art some power over her dependent economic condition; she was at last a professional novelist. Around the same time, she copied into a notebook the hastily terminated novel-in-letters, Lady Susan. Why do that? Was it an act of scribal housekeeping? Was she drawing a line under one kind of experiment in female psychology (the scheming of a middle-aged sexual predator jealous of her teenage daughter) as she sketched the outlines for another (the narrow domestic confinement of four marriageable women)? According to one Austen family tradition, The Watsons was to pit the youthful Emma Watson against an older female rival, Lady Osborne, a woman “very handsome” “tho’ nearly 50” (b3: 8; MW 329), for the attentions of the much younger clergyman Mr. Howard.4 The suggestion of creative synergy between Lady Susan and The Watsons foreshadows what we know was the future for The Watsons itself, elements of which resurface in the published novels.

Was The Watsons broken off when Austen’s father died and real life collided uncomfortably with the outlines of her latest fiction?5 The manuscript, graphically Austen’s most disordered and unresolved, does not suggest a novel; rather, it appears to be a novella or long short story, like the unfinished “Kitty, or the Bower” in Volume the Third. Like “Kitty,” it is written continuously, without chapter divisions or other strong structural markers. Did The Watsons simply run out of fictional steam? It may have had no real grounds for growth in it. As a fragment, however, it was quarried, plundered, and recombined over time; it became a salvage site. Lord Osborne, cold and careless, “out of his Element in a Ball room” (b4: 1; MW 329), is only slightly more dysfunctional in female society than Mr. Darcy. The snobbish Mrs. Robert Watson, she of the Croydon smart set, was originally blessed with a son, John, at some point altered to a daughter, Augusta (b8: 6). Mrs. Robert Watson is surely relaunched as the social intruder Mrs. Augusta Elton in Emma.

As for Emma Watson, she promises to be a new kind of heroine, shaped by and vulnerable to environment, in the style of Fanny Price and Anne Elliot. There is no interesting pathology to explore in cast-off Emma Watson, her character already a little too fixed, but could Austen have dug down to find the emotional complexity of her later heroines without the experiment in social meanness that is The Watsons? The Watsons is, in retrospect, a hinge between early and later Austen. Greeting its appearance in print in 1871, the Victorian critic Anne Thackeray detected in it the “anteghosts, if such things exist,” of the later fiction (159). Shadowy duplication, the haunting of one fiction by another, is such a persistent feature of Austen’s way of working that it posits the fragment less simply as a structure aborted than as a creative imperative, a kind of test ground. A dark re-run of the lighter elements of “First Impressions,” The Watsons both recycles and anticipates the novel that became Pride and Prejudice while it appears to reach forward to Mansfield Park and Emma. It also demonstrates an important truth: fragment art involves risk.

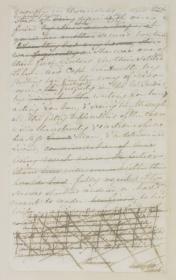

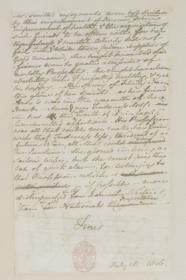

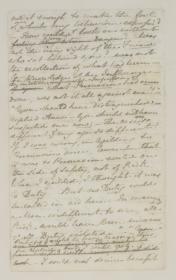

In fragments we see the bones laid bare of Austen’s way of writing: the importance of repetition with variation as a structuring principle; her reliance on immanent or processive composition. Her most illuminating fragment is the discarded ending to Persuasion—a master-class in how not to finish a novel. Its two chapters, surviving as a thirty-two page manuscript booklet, provide unusually detailed evidence of a sequence of timed intentions to resolve its ingredients: an ending, dated “July 16. 1816” (27; fig. 2), itself composed of several layers of text, some deleted, though it is impossible to untangle with certainty those deletions made before or after the temporary completion of July 16; a second ending, dated two days later, “July 18. 1816” (28; fig. 3), building on and developing elements from the first ending; and, following the second ending, a further three full pages of text (29–32), providing an ironic comment on that much favored “Finis” at the foot of pages 27 and 28. In their purpose of explanation and excuse, these extra pages offer a miniature resolution of their own, designed to be inserted towards the close of the previous draft chapter, chapter 10, and to deepen, through Wentworth’s more attentive act of retrospection, what was, at an earlier stage, run through too rapidly. It comes as a surprise to find that it is only in these late-added three pages (materially, the latest addition of all to the manuscript draft) that Austen sets her heroine to speak of the ethical and emotional rights and wrongs of “persuasion”: the word occurs three times on page 30 (fig. 4).

Figure 2 |

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

| Figure 2: Persuasion, draft manuscript p. 27, first attempt at an ending Figure 3: Persuasion, draft manuscript p. 28, second attempt at an ending Figure 4: Persuasion, draft manuscript p. 30, part of the insertion written after the two attempted endings, introducing the word “persuasion” three times |

||

Several passages of dense revision in the Persuasion draft manuscript, reinforced by the markedly different focus of the print ending, make it clear that Austen had no firm structure in place to anticipate or guide her as she wrote. There is evidence of rapid, even awkward, writing, of disconnection from a deeper purpose, not simply or even chiefly witnessed in the narrow scope within which Anne Elliot and Wentworth’s reconciliation is resolved in this discarded ending; its scene as first drafted at the Crofts’ lodgings is, in fact, well plotted and comically satisfying. If, as seems likely, the importance of teasing out the implications of “persuasion” struck Austen as an after-thought, there are other more disturbing examples of a late struggle to resolve significant elements of the narrative in the final pages.

The heavily deleted passage at page 21, with its contrived and indirect confrontation of Lady Russell’s necessary change of heart over Wentworth, is difficult to decipher graphically (in part because, without margins, Austen writes her substituted version between the lines of the deleted passage); it is also gnomic in intention. Austen appears to have written, as a first draft, the following:

Bad Morality again. A young Woman proved to have more discrimination of Character than her elder—to have seen in two Instances more clearly what a Man was it was about than her Godmother!—But on the point of Morality, I confess myself almost in despair after understanding ^myself to have ^already given a mother offence (having already appeared weak exactly in the point where I thought myself most strong) and shall ^therefore leave it ^the present matter to the mercy of Mothers & Chaperones & Middle-aged Ladies in general—; (P 21.5–19; P 282 n.23)

It is impossible to exaggerate the oddity of this section. Jocelyn Harris has described it well as a “frantic paragraph” (65). Austen had already written (and possibly already deleted) a passage where Anne Elliot appears to gloat over Lady Russell’s mistaken good opinion of Mr. Elliot (P 1.10–14; P 274 n.6). On the surface, she appears to exult again in her old friend’s poor judgment, but that only takes us to the second sentence. Much of the satisfaction of Persuasion is accounted for by the narrative’s infusion with the personality of its central character, Anne Elliot. It is not just that with the direct intrusion of the narrator’s voice this communion breaks down, but that that voice now seems to be elsewhere, communing with itself on a different matter: who is the mother the narrator has offended? Are we inside or outside the story? A gap has opened, leaving character and story temporarily adrift from their narrator. This is not the moment, so close to the novel’s ending, to lose fictional control.

It comes as a relief that Austen cancelled the entire section and recast it completely in more balanced and neutral terms. In revision Anne’s relationship to Lady Russell is tactfully repaired and the even temper of the narrator’s voice restored:

There is a quickness of perception, ^in some a nicety of Taste in the discernment of character—a natural Penetration in short in some which no Experience in others can equal—and revealing that Lady R. had been less gifted in this < > part of Understanding than her young friend (P 21.5–13; P 270)

In the struggle to bring Persuasion to a conclusion, are there intimations of a deeper disruption than the regular risk-taking style of the immanent writer? Only months later, Austen began Sanditon.

![]()

As Milnes suggested, biography plays a significant part in how we understand fragment art. The opacity of his judgment intensifies the mystery he attributes to Keats’s fractured forms. These “Literary Remains” are

so fragmentary as more becomingly to take their place in the narrative of the author’s life, than to show as substantive productions. Yet it is, perhaps, just in verses like these that the individual character pronounces itself most distinctly, and confers a general interest which more care of art at once elevates and diminishes. (1: 282)

Sanditon, styled at this stage “The Last Work,” made its first public appearance in 1871, over fifty years after Austen abandoned it. Written into three substantial homemade booklets, it was published as “extracts” only, its 120 manuscript pages reduced to twelve printed pages of selective quotation and plot summary absorbed into the body of the second edition of her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh’s Memoir of Jane Austen, where, as chapter 13, it made part of the story of the author’s life, tied to details of biography rather than to artistic development.

The unique features of manuscripts, their unmediated rawness—the disposition of words on the page and the sense of the hand’s imprint on the paper, both translatable as habits of mind as well as pen—enforce the place of biography in composition and the critical process. All manuscript drafts written in the author’s own hand invite us to connect art to life. James Joyce’s draft page, as Daniel Ferrer reads it, is a unique physical identifier or map of the writer’s personality: “The physiognomy of the draft page is a most individual characteristic, like a kind of thumbprint of the writer’s mind: it is a space of complete freedom that he occupies as he pleases. . . . It bears the imprint of his will, of his habits, of his compulsions” (265).

Last writings are credited with expressing this organic union in extreme form. Here, if anywhere, we expect the relationship between the self that makes and the thing made to appear harmonized and timely. Jane Austen bowed out of Sanditon in the course of chapter 12, its final words—“Poor Mr Hollis!—It was impossible not to feel him hardly used; to be obliged to stand back in his room ^ own House & see the best place by the fire constantly occupied by Sir H. D.”—followed by the date “March 18” (b.3: 39–40; MW 427). Exactly four months later, on 18 July, she died. Austen-Leigh worked up the evidence to a fine sentimental pitch, describing the manuscript’s “latter pages . . . first traced in pencil, probably when she was too weak to sit long at a desk” and its final dating as fixing “the period when her mind could no longer pursue its accustomed course” like “the watch of the drowned man indicates the time of his death” (127).

But the facts are other: only thirty-one lines of booklet two (2: 37–38) were traced first in pencil, and the manuscript continues for a further fifty pages in ink in a firm hand, while the date on the opening page of the third booklet (“March 1st”) makes it clear that the last forty pages were all composed in under three weeks. There is the awkward matter, too, of one of its central topics—hypochondria. Sanditon is a study of people who imagine they are ill by a woman we know was dying. But did she know this in January–March 1817? And, supposing she did, why should she reconcile her art to her life?

In his own dying meditation on style, Edward Said considered the relationship between “bodily condition and aesthetic style” and how, “near the end of their lives,” the work of great artists “acquires a new idiom,” which he calls “late style.” Late style, he contends, need not imply reconciliation, serenity, ripeness, or a sense of completion; rather, he asks, “what of artistic lateness . . . as intransigence, difficulty, and unresolved contradiction”? He continues: “I’d like to explore the experience of late style that involves a nonharmonious, nonserene tension, and above all, a sort of deliberately unproductive productiveness going against” (3–7). After Said, Gordon McMullan has argued that among the criteria for attributing late style is change, understood as soaring creativity, what McMullan also describes as a “caesura,” a break with what has gone before (3, 65, 18). It is not coincidental that McMullan places the origins of “late writing” as a special category of genius in the biological thought of German Romantic philosophers, Austen’s contemporaries, from whom we also derive our conceptualizing of fragment art.

But Austen’s earliest editors held symmetry and proportion in high esteem; for them her sensibilities were Augustan and pre-Romantic. Embarrassed by the teenage writings, discomforted by the mess and struggle of the manuscript page, they were not ready to admit Gilpin’s Palladian-destroying mallet among her tools; such a weapon could be wielded only by an alien, someone beneath or beyond the perfected print novelist. The problem of Austen’s last writings, as they saw it, was how to account for unseemliness rather than soaring creativity. Austen-Leigh defended his extreme redaction of Sanditon by discovering signs of failing power in the graphic evidence of the manuscript. As late as 1948, R. W. Chapman, who had published the first complete transcription of Sanditon in 1925 under the title Fragment of a Novel, expressed apprehension at its “harshness of satire”: had she lived, he confided, “she would have smoothed these coarse strokes” (208). For these early curators of her legacy, the late dissonance between art and life, the unguarded sense of liberties taken with both, is all the more disturbing in a writer whose reputation was built upon lifelikeness.

Austen’s last work has long seemed to its readers loaded with contradiction: last, but surprisingly reminiscent of the zany humor and freakishness of her teenage squibs.6 Does it announce a radically new style of writing and a new social vision or the place where fragment art tips finally into ruin? Tony Tanner’s remarkable reading of the mid-1980s described a work thoroughly compromised by exhaustion and disassociation. Playing upon the homonymic affinity of “Sanditon” and the rhetorical term “Asyndeton,” he argued that “Sanditon is built on—and by—careless and eroding grammar”; his verdict: “She is writing herself out of the world she is writing about” (260, 284). Then again, at eighty pages Sanditon’s final homemade booklet is probably the fattest Austen ever made. Only forty pages are written over, but, with so many pages still to be filled, do we have here a sign that this most economical of writers refused to go gently? Rather than timeliness and thrift, do we find defiance (“unproductive productiveness”) in its materials as in its boldly experimental subject matter?

Like variants in a text, last writings are pressure points, or, to change the metaphor, they are places where the expected path forks, stopping us in our critical tracks. Last writings are dead ends, and they are frail survivors; they trace what might have been. When the last work is a fragment, the sense of rupture with what has gone before is especially intense—more so, if we suppress the fact that Austen was always a fragment writer. But even among many fragments, a final fragment holds a particular place, its incompleteness generates a more intense longing (Janowitz 10).

Part of the challenge Sanditon poses is that it is undoubtedly the finest example of Austen’s fragment art, shot through with fragmentation at every level: stylistic and structural. Unfinished, in some ways barely begun, it is also available as a fully readable structure whose fragment characteristics are thematic as well as formal: it is a study in fragments of a society in fragments. In Sanditon, Austen describes a world opening up to change after decades of war. Like Persuasion, Sanditon turns its satirical focus upon the landed gentry who no longer responsibly maintain their estates and who, in consequence, no longer guarantee the nation’s stability. In Persuasion, whose action takes place during the false peace before Waterloo, Austen aligned herself with the values of the rising professional classes: men like her sailor brothers, whose advancement is by virtue of merit and risk—much as her own progress had been as a professional novelist. But in the post-war climate of boom and bust, the sailor’s meritorious risk has been replaced by the sheer recklessness of landed men like Mr. Parker, who abandons his family estate for property speculation in a new seaside resort.

Mr. Parker is a type of modern man, dislocated by recent events and wishing to make the world anew. We first meet him as he scrambles out of an overturned carriage (the first overturned carriage since the teenage burlesque “Love and Friendship”), the accident a consequence of his ridiculous misjudgment that the road he travels (no more than a “rough Lane” [b1: 1; MW 363]) leads somewhere. The appropriateness of the fragment’s unfinished status to its subject matter of rash speculation, misinformation, and wrong turns, of risk exposed, is irresistible. In his optimistic way, Mr. Parker is laying waste, breaking up the old order, tearing up one kind of socio-economic agreement between landlord and local community and negotiating new private contracts. The fragment form enacts the jeopardy and vanity of his new-built schemes.

But not just those of Mr. Parker. In Sanditon communication and narrative organization alike break down under the obsessive energies of a range of idiosyncratic projectors and imaginists each trapped within their own new-built schemes, their bizarre thought bubbles and unique ideolects: the meddlesome do-gooder Diana Parker, who wages a paramilitary campaign of officious helpfulness (“she was now regaling in the delight of opening the first Trenches of an acquaintance with such a powerful discharge of unexpected Obligation” [b3: 15; MW 414]); the Lovelace impersonator Sir Edward Denham, whose hyperbolic ravings despoil vast swathes of contemporary literature. The speech of both, largely constituted as monologue not conversation, regularly hits the page fully textualized; almost no revision is required. In Sanditon, Austen has shed all but her immanent writing strategies; composition appears as freewheeling and unresolved as the schemes of her eccentrics.

In contrast to their easy fluency is the graphic struggle to lock detail into a wider scheme, visible in the effort required to provide an integrated purpose for the non-eccentric Charlotte Heywood, who may or may not fill the role of conventional heroine. The rehashed moralizing of both parable and eighteenth-century ruin poetry hangs over this world of fragments, foregrounded in the unusual analytical method bestowed on Charlotte, trying to make sense of a world she can neither enter nor fully comprehend. The closing lines of chapter 7 reveal her feeling her way towards an opinion of Lady Denham, Sanditon’s most important landowner. The passage begins: “She is thoroughly mean. I had not expected anything so bad”; or, rather, that is how its opening words are finally resolved. It was first put down as “She is much worse than I expected—meaner—a great deal meaner.—She is very mean” (b2: 40). But, then, Austen breaks up those repeated phrases, deploying them across a wider space, rewriting from inside the initial burst of composition and expanding the passage as she recycles its phrases—a characteristic method evident throughout her career at the level of both style and substance:

“She is thoroughly mean. I had not expected anything so bad.—Mr P. spoke too mildly of her. . . . He is too kind hearted to see clearly . . . But she is very, very mean.—I can see no Good in her. . . . And she makes every body mean about her. . . . And I am Mean too, in giving her my attention. . . . Thus it is, when Rich people are Sordid.” (b2: 40; MW 402)

The contrived particularity of numerous small revisions throughout enhances the narrative’s general air of mystery and the heroine’s apparent function as piecemeal collector of evidence and purveyor of truisms. There are clear signs, too, of the same labor to maintain control as in the aborted ending to Persuasion, where the narrator’s complicity with her heroine (what James Wood calls “a kind of secret sharing” [8]) breaks down. What Tanner identified as “a rather new kind of perceptual limitation” (282) in Austen’s way of writing, already detectable, I would argue, in the draft ending to Persuasion, connects seamlessly in Sanditon with its overarching preoccupation with human delusion, at the heart of which is the speculative venture that Sanditon (the town built upon sand) represents.

There is something satisfyingly appropriate about Sanditon’s fragmentariness. A conspiracy between dissociated style and subject matter appears to have willed it into being as a designed fragment and a type of what Said calls the “unproductive productiveness going against” of late creativity—in Austen’s case, a creativity stripped back to its creative essentials. At the same time, as the last fragment, Sanditon is more accidentally so than those “anteghosts” for which the repetitive and recycling economies of the finished novels enact reparation. If Sanditon is Austen’s finest experiment in fragment art, it is also a ruin.

In Sanditon ruin is modified as fragment, much as the pathological and wasting processes of disease are reinterpreted in the Parker siblings as illness, which, unlike disease, is a state of being with privileges. After all, the dying novelist’s real secret sharer is not clear-sighted Charlotte Heywood but the deluded hypochondriac Miss Diana Parker, like Austen a resident of Hampshire and a martyr to bile. Herein lies the ultimate irony posed by the fragment artist: that we, her critics and readers, cannot distinguish fragment from ruin, waving from drowning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

All images included in this essay are copyrighted to Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts: A Digital Edition and used with permission of the holding libraries.

NOTES

1Gilpin’s comment was prompted by visiting Scaleby Castle, destroyed during the civil wars of the seventeenth century. Gilpin is acknowledged several times in Austen’s teenage writings (see, for example, Teenage Writings 92, 127). In his “Biographical Notice of the Author” (1818), Henry Austen described his sister as “at a very early age . . . enamoured of Gilpin on the Picturesque” (Austen-Leigh, Memoir 140–41).

2During the Second World War, Kenneth Clark, art historian and Director of the National Gallery, London, was chairman of the War Artists Advisory Committee, commissioning John Piper and Graham Sutherland to paint bomb sites as they still smouldered. “Bomb damage is in itself Picturesque,” Clark declared. Clark’s early research had resulted in his classic study The Gothic Revival (1928). See Christopher Woodward (212ff.). Jane and Louise Wilson’s “Blind Landings” (2013), in Tate Britain, explores the derelict H-bomb test site at Orford Ness in Suffolk.

3For Milnes’s exaggeration of the fragmentary nature of Keats’s art, see Jonah Siegel (130–33).

4Cassandra Austen’s suggestions for how her sister planned to develop the novel are recorded in James Edward Austen-Leigh’s A Memoir of Jane Austen (2nd ed. [364]).

5According to her great-niece Fanny Caroline Lefroy, “Somewhere in 1804 [Jane Austen] began ‘The Watsons,’ but her father died early in 1805, and it was never finished” (277).

6See, for example, Clara Tuite: “I also wish to engage the curious conjunction between dystopia and utopia, the backward look and the forward look, old and new styles, which Sanditon embodies” (158).