Between March 29 and April 8, 2017, Cambridge University Library marked the bicentenary of Jane Austen’s death by exhibiting some of its rare Jane Austen holdings. Jane Austen’s letters and the accompanying items in the exhibition, reproduced below, document two very different times in Austen’s life: the period of the Austen family’s move to Bath in 1801, before Austen was a published author, and the period around the publication of Emma in December 1815, when, although her work was still published anonymously, it was admired by aristocracy and royalty, and she was acknowledged as an innovative writer by one of the most celebrated authors of the day.

Only about 160 letters written by Jane Austen, of what Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade estimates as some 3,000 written over the course of her life, survive (31). In this exhibition, “Jane Austen: Letters and Readers,” three Jane Austen letters held in different Cambridge collections were displayed alongside printed works from the University Library. This was the first time that these letters, which cannot otherwise be seen in one viewing, have been displayed together.

Much of the printed work in this exhibition comes from the collection of Austen’s first bibliographer, Geoffrey Keynes, including a book by Oliver Goldsmith signed by Jane Austen. Geoffrey Keynes’s bibliographies—of, among others, John Donne, William Blake, William Hazlitt, Rupert Brooke, as well as of Austen—relied significantly upon his own collections. When Keynes died in 1982, his scholarly papers, correspondence, and some 8,000 volumes from his library were acquired by the University of Cambridge. Another rare book signed by Jane Austen, in the possession of Geoffrey Keynes’s brother, the economist John Maynard Keynes, is described in James Clements and Patricia McGuire’s essay, “Jane Austen at King’s College, Cambridge,” in this issue of Persuasions On-Line.

In the descriptions of individual items that follow, bibliographical information is indebted to David Gilson’s Bibliography of Jane Austen, which built on Geoffrey Keynes’s Jane Austen: A Bibliography. (Gilson left his own major Austen collection to King’s College, Cambridge.) Information relating to the letters and their provenance is indebted to Deirdre Le Faye’s edition of Austen’s Letters.

Jane Austen and Bath

In December 1800 Jane Austen’s father, the Reverend George Austen, announced his decision to leave the family home at Steventon, Hampshire, a decision that apparently distressed Jane Austen (Le Faye 128). The following May the family moved to Bath, where they lived until the year after George Austen’s death in 1805. The five years that Austen lived in Bath may not have been her happiest, but it was a time that fed significantly into her creative work and certainly into the Bath novels Northanger Abbey and Persuasion.

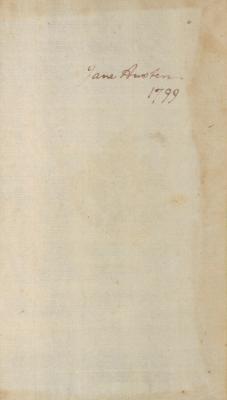

Oliver Goldsmith. An History of the Earth, and Animated Nature. London: J. Nourse, 1774. (Keynes.T.5.21)

Austen's signature |

James Leigh Perrot's bookplate |

| Front endpapers, vol. 1. By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. | |

Before the family moved to Bath in 1801, Jane Austen had visited there at least twice, in 1797 and in 1799. The multi-volume set of Goldsmith’s An History of the Earth, and Animated Nature represented above was perhaps presented to Jane Austen during that 1799 visit (Gilson K10; 441).

The first volume of this eight-volume work by Oliver Goldsmith (1728?–1774) is inscribed “Jane Austen 1799,” written when Jane Austen was twenty-three. All of the volumes have the bookplate of James Leigh Perrot, Austen’s maternal uncle, and were probably given to Austen by him with other books when she was visiting Bath in May and June of that year. There are very few books that Jane Austen is known to have owned. David Gilson lists twenty in his 1997 Bibliography (436-46). This volume is from the collection of Geoffrey Keynes.

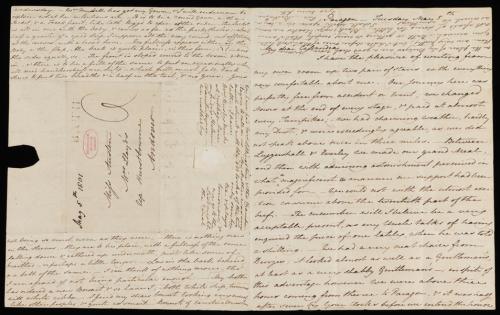

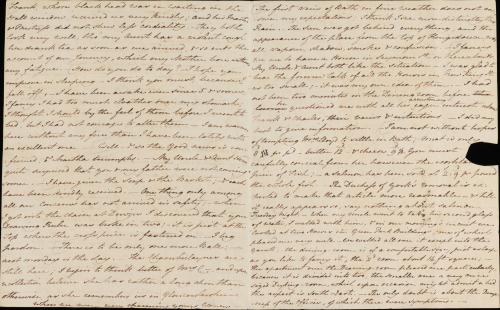

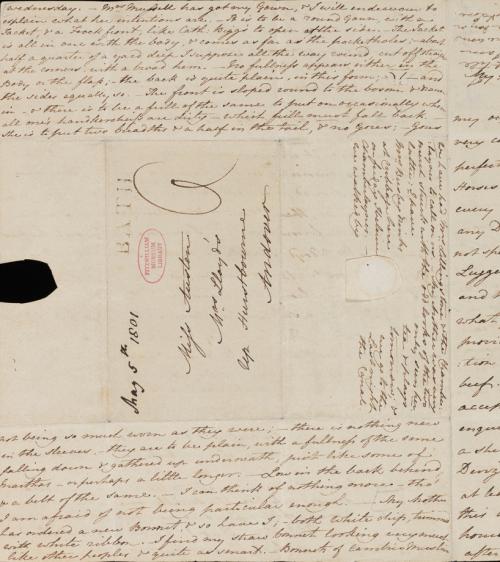

Jane Austen. Letter to Cassandra Austen. Bath, 5–6 May 1801. (Fitzwilliam Museum Gen/A/Austen/1 )

Jane Austen's letter: on left, page 4 with text of letter, address panel and seal; on right, page 1 with start and end of letter.

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Jane Austen's letter, pages 2 and 3.

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

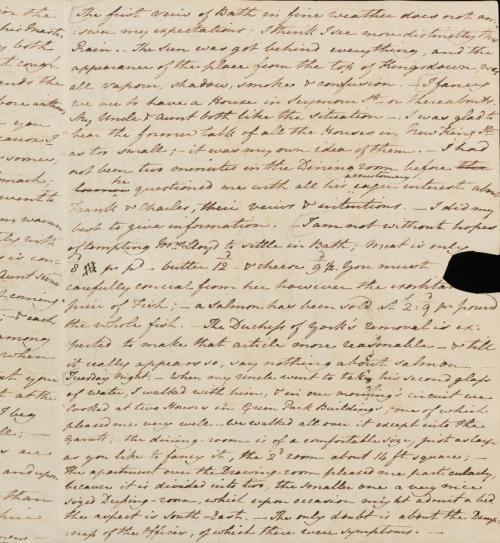

In the first letter of the exhibit, dated Tuesday 5–Wednesday 6 May 1801 (from the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum), Austen narrates for her sister, Cassandra, some of her initial impressions of the city. The letter is extremely rich in social detail—down to the inflated price of salmon.

This letter was written by Jane Austen on her arrival in Bath and is full of news about their journey, accommodation in Bath, the cost of food, and clothes (with Austen's simple illustration of a design for her own clothes: see line 7 on p. 4 in the first image below). Austen memorably described the city on arrival: “The first veiw of Bath in fine weather does not answer my expectations; I think I see more distinctly thro’ Rain.—The Sun was got behind everything, and the appearance of the place from the top of Kingsdown, was all vapour, shadow, smoke & confusion.”

Jane Austen's letter, close-up, p. 4,

with address and postcript below the address panel.

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Jane Austen's letter: close-up, p. 3,

beginning "The first veiw of Bath."

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Austen may not have enjoyed Bath, but she would set parts of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion there. In 1803, while Austen was living in Bath, the manuscript of Susan, an early version of Northanger Abbey, was sold to a London publisher, but it remained unpublished in Austen’s lifetime.

This letter was bequeathed by Cassandra Austen to Fanny, Lady Knatchbull, in 1845 and inherited by Lord Brabourne in 1882. The letter was sold at Sotheby’s in 1886. Lord Ashcombe gave this letter to the Fitzwilliam Museum Library in 1917 (Le Faye letter 35).

The New Bath Guide; or Useful Pocket Companion. A New Edition, Corrected and Enlarged. Bath: R. Cruttwell, 1777. (7460.d.38[1])

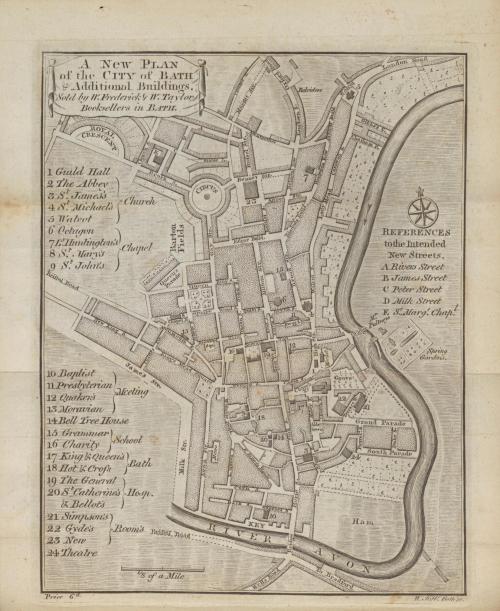

Cruttwell's map of Bath. Plate facing page 3.

By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

According to Austen’s nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh, the original sale of Susan (later revised to Northanger Abbey) in 1803 was to a Bath publisher (105). It is possible, according to David Gilson and others, that the Bath firm of Cruttwell, publisher of The New Bath Guide, provided the connection to Crosby & Company in London, with whom Susan languished until Henry Austen bought it back in 1816 (see Gilson 83).

Cruttwell specialized in print relating to Bath, as in this guidebook, with its folding map. Janine Barchas has speculated that Austen may have identified Cruttwell as offering a particularly receptive audience for her debut novel, which itself serves as a sort of guide to Bath (62–63).

Jane Austen. Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. By the Author of “Pride and Prejudice,” and “Mansfield-Park,” &c. With a Biographical Notice of the Author. London: John Murray, 1818. (Syn.7.81.10)

Northanger Abbey, vol 1, title page.

By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

The item above is one of two first editions of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, published posthumously in 1818, held in Cambridge University Library. This edition of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion contains the short, first biography of the author, written by Austen’s brother Henry.

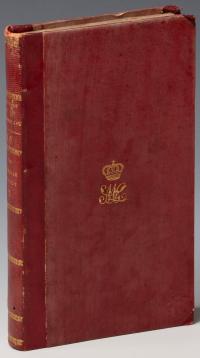

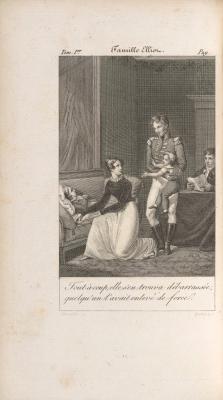

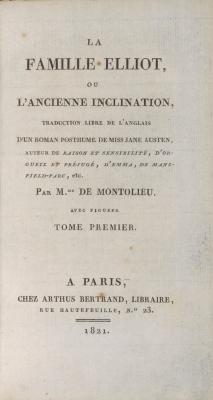

Isabelle de Montolieu, trans. La famille Elliot, ou L’ancienne inclination, traduction libre de l’Anglais d’un roman de Miss Jane Austen. Paris: Arthus Bertrand, 1821. (Keynes.K.2.15)

Frontispiece |

Title page |

| Frontispiece and title page. By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library | |

The first translation of Persuasion, by Isabelle de Montolieu (1751–1832), which appeared three years later in Paris, is the first translation into any language to mention Jane Austen’s name on the title-page. It is also the first illustrated edition of any Jane Austen novel, with frontispieces after Charles Abraham Casselat, engraved by Delvaux (Gilson C11; 167).

This copy of La famille Elliot was owned by Empress Marie Louise, second wife of Napoleon, and is bound in red morocco with her crown initials. The Napoleonic wars are a backdrop to Persuasion. The plot is facilitated by a seeming end to hostilities, allowing Wentworth to return to shore and to Anne Elliot (or Alice, in this translation).

Jane Austen: The author of Emma

The subsequent letters in this exhibition (from the collections of Cambridge University Library and King’s College, Cambridge respectively) are written by Austen as the author of Emma. Austen’s name was not yet widely known, and her novels were published anonymously. But these letters, to Frances Parker, Countess of Morley (31 December 1815) and to her publisher John Murray (1 April 1816) together document the reputation of her fiction. Emma contains Austen’s dedication to the Prince Regent. She was informed by his librarian, James Stanier Clarke, who also presumed to give Austen some detailed literary advice, that she might dedicate a work to the Regent (15 November 1815). This permission seems not to have given her much choice. The letter from Frances Parker, to which Austen’s is a reply, is also in the University Library’s collection and is reproduced here.

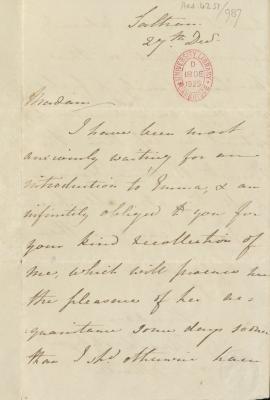

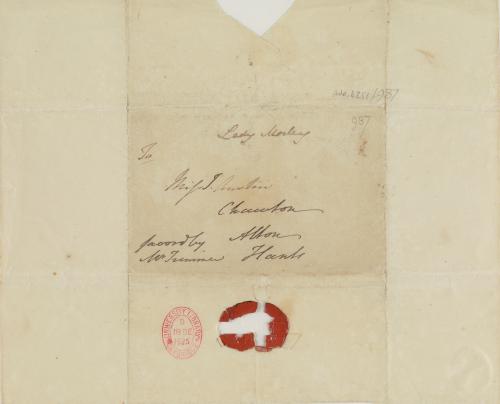

Frances Parker, Countess of Morley. Letter to Jane Austen. Saltram, Devon, Wednesday 27 December 1815. (Cambridge University Library, MS Add.4251/987)

| Countess of Morley to Jane Austen 27 Dec 1815. By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. |

|

The connection between Jane Austen and Frances Parker, Countess of Morley (d. 1857), is not fully known—it may have been through Austen’s brother, Henry—but Austen sent Parker a copy of Emma on publication (see Jarvis 12, 10). Frances Parker has become a significant figure in ascertaining private responses to Austen, about whose works she corresponded. Here Parker writes to Austen: “I am already become intimate in the Woodhouse family, & feel that they will not amuse & interest me less than the Bennetts, Bertrams, Norris’s & all their admirable predecessors—I can give them no higher praise.” In her private correspondence, however, she reported that she did not like Emma as much as Austen’s previous two novels, Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park (Le Faye 231). Parker was herself suspected to be the author of Austen’s early fiction (Jarvis 6). The letter’s wrapper, with the remains of its red wax seal, is also reproduced here. Written on it, in Jane Austen’s hand, is “Lady Morley.

Wrapper of letter from Countess Morley

By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

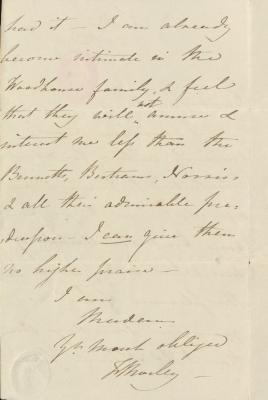

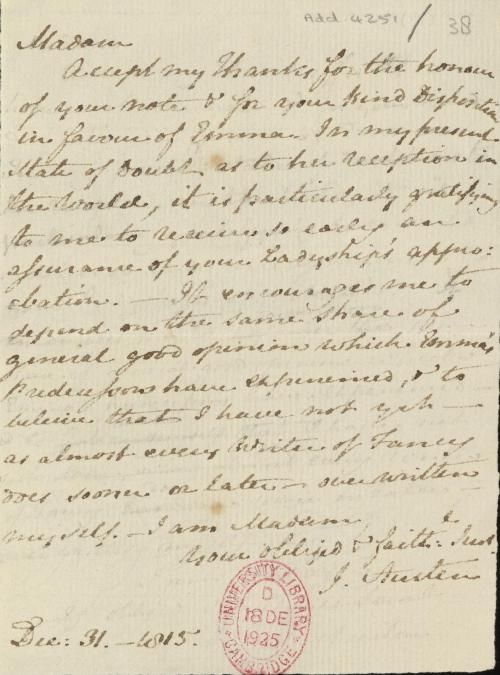

Jane Austen. Draft of a letter to Frances Parker, Countess of Morley. [Chawton], 31 December 1815. (Cambridge University Library, MS Add.4251/38)

Austen to Morley 31 Dec 1815

By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

This draft of Austen’s reply to Lady Morley was originally written in pencil, traces of which can be seen between the lines of ink (Le Faye 453). The near-identical letter that Austen sent to Lady Morley survives and is in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. In her letter, Austen claims to be encouraged by Lady Morley’s praise “to beleive that I have not yet—as almost every Writer of Fancy does sooner or later—overwritten myself.”

These two letters were bequeathed by Cassandra Austen to her brother Charles John Austen in 1845 and descended to his granddaughters. J. Pierpont Morgan bought them in 1925 and gave them to Cambridge University Library in the same year (Le Faye letters 134A and 134D).

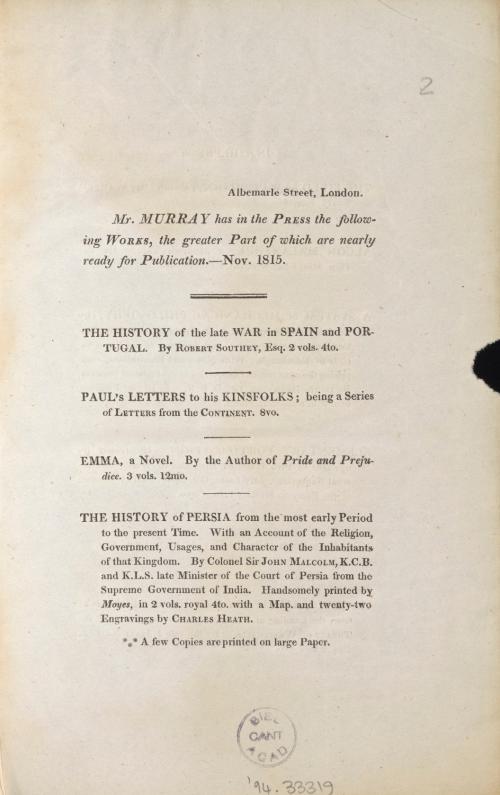

Helen Maria Williams. A Narrative of the Events which Have Taken Place in France; with an Account of the Present State of Society and Public Opinion. 2nd edn. London: John Murray, 1816. (Cambridge University Library, Leigh.c.11.143)

Advertisement

By Permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

The earliest advertisement for Emma is found in Helen Maria Williams’s A Narrative of the Events which Have Taken Place in France (above). The book, dated 1816, in original boards, has an inserted advertisement, dated November 1815 (see Gilson xxix).

Jane Austen. Letter to John Murray. Chawton, 1 April 1816. (King’s College, Cambridge, the Warren Collection, NM/AustenJ/1)

Austen letter to John Murray.

By permission of the Provost and Fellows of King’s College, Cambridge.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

In this letter to John Murray, who had published Emma in December 1815, Austen acknowledges Murray’s loan of a copy of the Quarterly Review, which included an unsigned review of Emma by Walter Scott.

Scott’s review was the first serious appreciation of Austen’s writing, which he saw as exemplifying a new style:

“We, therefore, bestow no mean compliment upon the author of Emma, when we say that, keeping close to common incidents, and to such characters as occupy the ordinary walks of life, she has produced sketches of such spirit and originality, that we never miss the excitation which depends upon a narrative of uncommon events, arising from the consideration of minds, manners, and sentiments, greatly above our own.” (193)

The three people named or described in Austen’s letter testify to Austen’s growing reputation: the influential publisher John Murray, who published novels infrequently (Sutherland 109) but had taken on Emma and published a second edition of Mansfield Park; the immensely popular Walter Scott (whether Austen knew it was he or not), who wrote the first substantial account of her fiction; and the Prince Regent, to whom Austen dedicated Emma, probably unwillingly. The “late sad Event in Henrietta St” that Austen describes was the bankruptcy of her brother Henry.

This letter was given to King’s College, Cambridge, by Dorothy Warren in 1990. It had been in the Murray archive and sometime after 1870 was probably given by a member of the Murray family to the 6th or 7th Earl Beauchamp of Madresfield Court. It was sold at Sotheby’s in 1975 (Le Faye letter 139).

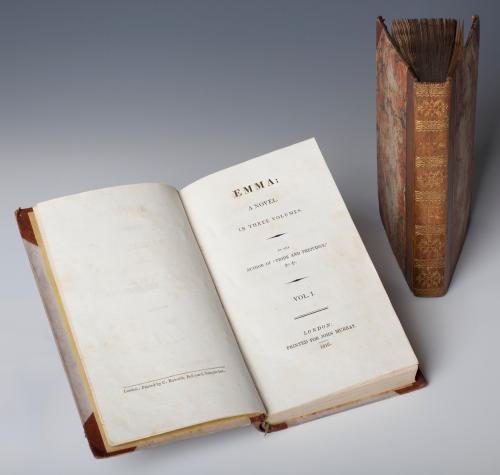

Jane Austen. Emma: A Novel. In three volumes. By the author of “Pride and Prejudice.” London: John Murray, 1816. (Keynes.K.2.3; Keynes.K.2.4)

Emma title page and binding.

By Permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

These volumes are from two of three first editions of Emma in Cambridge University Library.

Adding to Austen’s dedication of Emma to the Prince Regent, the rear copy in this image carries other, more distant, royal associations, containing the bookplate of Marie Luise Pauline de Courlande (1782–1845), the wife of Prince Friedrich Hermann Otto of Hohenzollern-Hechingen, a principality in South West Germany. A signature, “Catharine de Courlande,” probably that of the Princess’s sister, can be seen on the dedication page.

It is, of course, the nature of letters that they inhabit spaces far from their place of composition. The three letters written by Jane Austen that have made their way to Cambridge have done so by distinct routes, and they lie tantalizingly close to each other within Cambridge University’s collections. This exhibition was the first to unite them for public display, while this essay records that juxtaposition more permanently.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The exhibition was organized by Anne Toner and John Wells, Senior Archivist in the University Library. Thanks are due to Lucy Cheng, exhibitions conservator, Cambridge University Library, and to Jill Whitelock, Head of Special Collections, Cambridge University Library; to Stella Panayatova and Suzanne Reynolds at the Fitzwilliam Museum; and to James Clements, Peter Jones, and Patricia McGuire at King’s College, Cambridge. Thanks are also due to the Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Provost and Fellows of King’s College for the original loan of the Austen letters and for permission to reproduce them here and to the Syndics of Cambridge University Library for permission to reproduce material from its collection.