Jane Austen lived in a time of transformation, and her novels speak to the growing social mobility of the era and the ideals of individualism and equality. In Persuasion, Austen explores the societal and economic changes that took place as power and civic virtue shifted away from the landed class, as exemplified by Sir Walter Elliot, and toward the middle class, represented by the men of the meritocratic navy. In this novel, Austen mentions up-to-the-minute furnishings and dress to elucidate society’s state of alteration.1

The narrator of Persuasion describes the homes and styles of Mr. and Mrs. Musgrove and their family members:

To the Great House accordingly they went, to sit the full half hour in the old-fashioned square parlour, with a small carpet and shining floor, to which the present daughters of the house were gradually giving the proper air of confusion by a grand piano forte and a harp, flower-stands and little tables placed in every direction. Oh! could the originals of the portraits against the wainscot, could the gentlemen in brown velvet and the ladies in blue satin have seen what was going on, have been conscious of such an overthrow of all order and neatness! The portraits themselves seemed to be staring in astonishment.

The Musgroves, like their houses, were in a state of alteration, perhaps of improvement. The father and mother were in the old English style, and the young people in the new. Mr. and Mrs. Musgrove were a very good sort of people; friendly and hospitable, not much educated, and not at all elegant. Their children had more modern minds and manners. . . . Henrietta and Louisa, young ladies of nineteen and twenty, . . .were now, like thousands of other young ladies, living to be fashionable, happy, and merry. Their dress had every advantage, their faces were rather pretty, their spirits extremely good, their manners unembarrassed and pleasant; they were of consequence at home, and favourites abroad. (43)

In the Georgian era, the term “improvement” meant alteration that was undertaken for social, economic, aesthetic, or moral ends (Daniels 2). One of the most famous “improvers” of Austen’s time was the landscape gardener Humphry Repton. He produced before-and-after views, using a paper overlay, to show the effects of his improving designs, collecting the sets of drawings for each client in his Red Books, so named because of the color of the bindings.

Austen knew about the work of Repton; whether she admired him is not known. In 1802, her mother’s cousin the Reverend Thomas Leigh hired Repton to suggest improvements to the estate at the rectory and main house at Adlestrop (Barchas 197). While Jane Austen, her mother, and her sister were visiting their cousin there in 1806, the Reverend was called to Stoneleigh Abbey, which he had unexpectedly inherited, and he invited his cousins “to accompany him to what Jane Austen later described as one of the finest estates in the country” (Batey 20). In 1809, Repton made suggestions for alterations to the land surrounding Stoneleigh Abbey and produced a Red Book for the project. Scholars believe that Austen had read publications about landscape aesthetics since her childhood (Barchas 42). Janine Barchas has observed that, given the family connection, it would not be unreasonable to suppose that, after learning of Repton’s Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803), in which Adlestrop is featured, Austen would have read it and other publications by him (197).

There were objections by some of Repton’s contemporaries to his improvements when they involved the demolition of traditional landscapes, the arbitrary felling of trees, the creation of lakes in the forms of fake rivers, and the relocation of unattractive villages that ruined picturesque views. In Mansfield Park, in which Repton is mentioned by name, Jane Austen seems to condemn him for the destruction of ancient structures and the customs of life they enabled (Bolus-Reichert 213). Alistair Duckworth points out, however, that Repton’s writings promote ideas of improvement that often seem to be in alignment with Austen’s own views:

His emphasis on “utility,” his insistence . . . upon a “due attention to the character and situation of the place to be improved” align him with, for example, Edward Ferrars in Sense and Sensibility, whose “idea of a fine country . . . unites beauty with utility” and who finds “more pleasure in a snug farm-house than a watch-tower.” (42)

Duckworth observes that “[a]fter a temporary enthusiasm for ‘rocks and mountains,’ Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice settles for Darcy’s tastefully improved estate” (42). Indeed, Elizabeth comes to see that the balance between art and nature at Pemberley reflects Darcy’s good character and excellent taste (Zohn). Austen shows that true improvement cannot be merely for show.

The author also espouses this view in Persuasion. In elevating a farmhouse into their cottage, Charles and Mary Musgrove have concentrated on aesthetic appearance, “with its viranda, French windows, and other prettinesses” (P 39), more than on the function and use of the building (Duckworth 185).2 Tony Tanner has remarked that Sir Walter and Elizabeth Elliot’s new interiors at Camden Place are indicative of their “ludicrous snobbery, chilly hauteur, unpleasant seeming-politeness, and mean-spirited pseudo-etiquette” (225). The alterations put into place by self-made naval officers and their families, however, such as the “few alterations” made to Kellynch Hall by Admiral and Mrs. Croft, are “all very much for the better” (P 138). Captain Harville, whom Anne Elliot finds “unaffected, warm, and obliging” (105), has fitted up his family’s small abode to be “the picture of repose and domestic happiness” through his “ingenious contrivances and nice arrangements” (106).

The narrator comments that the daughters’ additions to the parlor at Uppercross have resulted in a “proper air of confusion” (43, emphasis mine). The description of the room seems to echo Repton’s thoughts from the 1803 publication that includes Adlestrop, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening:

Modern habits have altered the uses of a drawing-room: formerly the best room in the house was opened only a few days in each year, where the guests sat in a formal circle, but now the largest and best room in a gentleman’s house is that most frequented and inhabited: it is filled with books, musical instruments, tables of every description, and whatever can contribute to the comfort or amusement of the guests,3 who form themselves into groups, at different parts of the room; and in winter, by the help of two fire-places, the restraint and formality of the circle is done away. (185, emphasis mine)

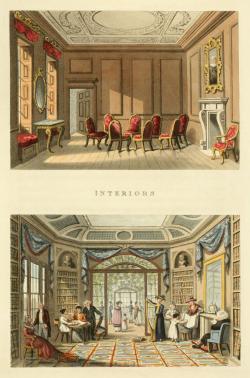

From Humphry Repton’s Fragments of the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1816).

From Humphry Repton’s Fragments of the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1816).

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Repton indicates that modern furniture arrangements lead to convivial interactions among friends and family.

The fact that these habits are still being practiced as Austen was composing Persuasion is illustrated in Repton’s 1816 publication, Fragments of the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening. He writes,

Since the chief object of this collection of Fragments is to bring before the eye those changes or improvements, which words alone will not sufficiently explain, two sketches are introduced, to shew the contrast betwixt the ancient cedar parlour and the modern living room: but as no drawing can describe those comforts enjoyed in the latter, or the silent gloom of the former, perhaps the annexed lines may be allowed to come in aid of the attempt to delineate both. (57–58)

Then follows a poem to accompany two illustrations:

A MODERN LIVING-ROOM

No more the Cedar Parlour’s formal gloom

With dulness chills, ’tis now the Living Room;

Where Guests, to whim, or taste, or fancy true,

Scatter’d in groups, their different plans pursue.

Here Politicians eagerly relate

The last day’s news, or the last night’s debate,

And there a Lover’s conquer’d by Check-mate.

Here books of poetry and books of prints

Furnish aspiring Artists with new hints;

Flow’rs, landscapes, figures, cram’d in one portfolio,

There blend discordant tints to form an olio.

While discords twanging from the half-tun’d harp,

Make dulness cheerful, changing flat to sharp.

Here, ’midst exotic plants, the curious maid

Of Greek and Latin seems no more afraid.

There lounging Beaux and Belles enjoy their folly,

Nor less enjoying learned melancholy.

Silent midst crowds the Doctor here looks big,

Wrap’d in his own importance and his wig. (58)

In using the term “Cedar Parlour,” Repton refers to the fact that throughout the baroque era, in the seventeenth century, rooms were commonly lined with wood wainscoting or paneling. Oak was most frequently used, but cedar and other woods were installed as well (Beard 85–86). In fact, in Austen’s favorite novel, Samuel Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison, the cedar parlor in Selby House is the favorite room of Harriet Byron. James Edward Austen-Leigh remarked that his aunt knew “Every circumstance narrated in [Richardson’s novel], all that was ever said or done in the cedar parlour, was familiar to her” (qtd. in Southam 9). Wainscoting provided an attractive background for paintings, like the Musgroves’ “portraits against the wainscot” in their “old-fashioned square parlour” and the portrait above the mantel in Repton’s illustration.

The boards of the floor of Repton’s cedar parlor are uncovered, while only a “small carpet” covers the Musgroves’ “shining floor.” A new innovation in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was the fitted carpet, upon which the furniture in Repton’s living room is placed. Wall to wall carpets were made in thin strips a few feet wide and cut and sewn together on site to fit the room (Yorke ch. 5). There were two types: loop-pile Brussels and cut-pile Wilton carpets. The latter were about double the cost of the Brussels due to the effort involved in cutting the pile (“A Brief History”).

The main reception and living rooms that had been on the first floor during the baroque era4 moved to the ground floor to allow for access to the conservatory or gardens (Thornton 153). In Repton’s living room, a conservatory can be seen through an open door and surrounding glass windows that come all the way down to the carpet. This space feels more airy and open than the paneled, square parlor.

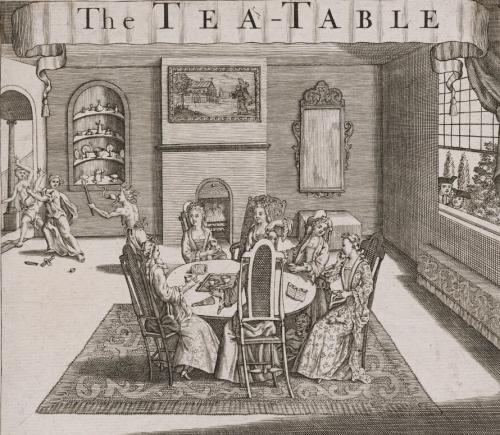

The Tea-Table, by John Woodward (1766).

The Tea-Table, by John Woodward (1766).

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

In a baroque-era parlor, the standard location of furniture was against the wall, but it could be moved around as needed for different activities. A print from 1766 shows a tea table and chairs placed onto a “small carpet” surrounded by a “shiny floor.” In Repton’s cedar parlor, a group of chairs has been set in a “formal circle” in the middle of the room. This placement indicates that all of the people seated there would have been taking part in the same discussion, an arrangement that could have a deadening effect on conversation. As Robin Evans has commented, the interaction in Repton’s room would have been “obsequiously directed by one elderly and overbearing figure, the matriarch, whose domineering presence was symbolized by the portrait on the wall” (215). A passage from December 1782 in the diary of Frances Burney demonstrates that even by that time some people were trying to avoid “the circle.” Burney describes a visit to a fashionable home in London, where the hostess said, “‘My whole care is to prevent a circle.’ Rising hastily, the lady then pulled about the chairs, and planted the people in groups with as dexterous disorder as you would desire to see” (qtd. in Thornton 149).

Eventually, a desire for a more relaxed way of life led to the practice of furniture being permanently placed away from the walls in clusters around the room (Thornton 147). Repton’s living room reflects this new practice. People are seated on a miscellaneous selection of chairs, “scattered in groups,” as Repton says, as they take part in a variety of activities, such as conversing, playing the harp, and reading alone and together. The narrator of Persuasion portrays the sociable atmosphere of the Musgroves’ parlor at Christmas time: “On one side was a table, occupied by some chattering girls, cutting up silk and gold paper; and on the other were tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies, where riotous boys were holding high revel” (145). Observing this scene, Mrs. Musgrove appreciates the “little quiet cheerfulness at home” (146).5 This depiction brings to mind Repton’s living room, where “discords twanging from the half-tun’d harp / Make dulness cheerful, changing flat to sharp.”

Quartetto tables, attributed to Thomas Seymour, painting attributed to John Ritto Penniman (1804–1810).

Quartetto tables, attributed to Thomas Seymour, painting attributed to John Ritto Penniman (1804–1810).

National Gallery of Art, Washington.

As in the Musgroves’ parlor, a variety of little tables was placed around the room in the different seating areas. There were innovations in the types and uses of tables at the time. In 1807, Robert Southey described the new form of quartetto tables as “the nest of tables for ladies. . . . [Y]ou would take them for play things, from their slenderness and size, if you did not see how useful they find them for their work” (qtd. in Snodin and Styles 110). New technologies in lighting encouraged people to gather around a table so that they could see to work or read, instead of having to sit close to the fireplace for light. This new equipment led to round tables appearing in the drawing and other public rooms, with chairs set permanently around or pulled up as needed (Thornton 149). Plant and flower stands, often multi-tiered and of elaborate design, were popular accessories for interiors at this time (Shapard 75).

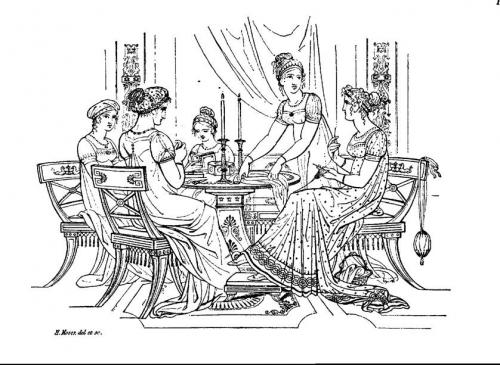

From Henry Moses’s Designs of Modern Costume (1812).

From Henry Moses’s Designs of Modern Costume (1812).

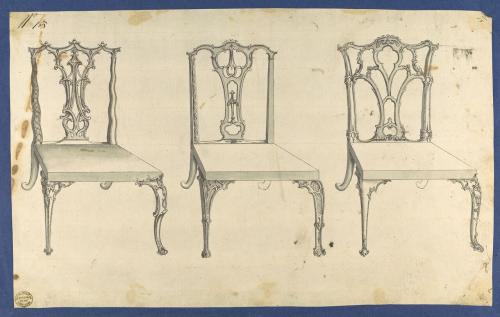

The elder Musgroves would have grown up with furniture produced in the richly carved and heavily ornamented style of the late baroque, or rococo, era in the middle of the eighteenth century. This style is epitomized by the designs of Thomas Chippendale in his famous pattern book, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1753–1770). Given their lack of elegance and education, the elder Musgroves may not have been interested in updating their old-fashioned parlor, but the modern-minded Henrietta and Louisa have taken up the task. Their additions would have been in a new style instigated by archaeological discoveries in Herculaneum and Pompeii that led to a renewed interest in the art of the classical world. Neoclassicism began to supplant the rococo in the 1760s, and by 1770 the change was complete. The work of Thomas Sheraton in his The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book of the 1790s exemplified the new style, which remained fashionable in the first two decades of the nineteenth century. Sheraton’s furniture obeys neoclassical devotion to simple geometry, in particular uncurving forms such as rectangular chair backs. Straight chair legs feature fluting, or sets of grooves, like the columns of a Greek temple.

From Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (p. XXII).

From Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (p. XXII).

From Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (plate 35).

From Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (plate 35).

A few decades after the style had become the norm in furnishings, neoclassicism entered the realm of fashionable dress. The attire of the turn of the nineteenth century employed less elaborate silhouettes and fabrics than had been used for hundreds of years. The goal of fashion had been to distort the body’s natural shape with the use of copious amounts of expensive fabric to indicate plenty, wealth, power, and prestige (Ribeiro and Cumming). At the end of the eighteenth century, however, there was a zeal for ancient Greek and Roman styles. This taste, combined with the break that came with the old order as a result of revolutions in America and France, encouraged those like Henrietta and Louisa, who were “living to be fashionable,” to leave behind what they saw as the frivolous and over-luxurious styles of their predecessors in the “old English style.”6 The transformation was dramatic: a woman who had attended a ball at George III’s court wearing an embroidered silk dress with wide skirts might later attend a ball at the Assembly Rooms at Bath wearing a thin white cotton muslin one.7

During the rococo era of the elder Musgroves’ youth, a woman’s upper body had been completely enveloped in fully boned stays, a foundation garment that creates a conical shape with pushed up breasts and a thin waist.

|

|

|

Robe à la Française (1740s). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Robe à la Française (1740s). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Anne Bissonnette and Sarah Nash have pointed out that, “although the breasts were exposed above the neckline—which could be very low—they were not seen as separate entities. The lower body was not exposed at all” (12). A wide silhouette was created by petticoats supported by panniers, meaning “baskets,” created from padding and hoops of different materials such as cane, whalebone, or metal. The garment that epitomized the era was the robe à la française. The silhouette is extended at the back by box pleats that fall loose from the shoulder to the floor. Women’s hairstyles were correspondingly elaborate, dressed high with pomade and dusted with white powder to draw attention to the face in candlelit-rooms. Red cheeks and lips contrasted with white faces produced with lead-based powder, which not only looked unnatural, but could be deadly, as well (Chambers).

|

|

|

John Hobart, Second Earl of Buckinghamshire, by Thomas Gainsborough. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

John Hobart, Second Earl of Buckinghamshire, by Thomas Gainsborough. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Men’s suits of the rococo era were cut full and could be heavily embellished with trim. An example from about 1760 has a long waistcoat (vest) covered by a knee-length coat with wide cuffs and a flaring skirt that emphasizes the lower torso. Men generally shaved their heads and wore wigs, sometimes powdered white.

The aim of the neoclassical appearance was a much more natural look, and the silhouette was simplified and slimmed down. Female dress was inspired by the styles worn by women in the Golden Age of Greece, illustrated by statues and paintings on vases that were being discovered in archaeological excavations. To imitate the clinging draperies of antiquity, the neoclassical gown had a low and softly rounded neckline, short sleeves, and a high waistline over a column-shaped skirt. This new style emphasized the beauty of the body’s natural lines. Divided corsets now delineated breasts as two distinct units, and the columnar silhouette revealed more of the size and shape of the lower body. This fashion could feel quite shockingly nude to those who were used to the wide skirts and panniers of earlier generations. Ladies arranged their hair in “antique” styles, and the natural look included wearing fewer cosmetics, especially giving up white face powder.8

|

|

|

|

A sleek and simple silhouette occurred in men’s neoclassical clothing, as well. Ancient sculptures of nude athletes, wherein every line of a man’s contours are on display, inspired the new ideal. It was conveyed in a high-waisted and narrow silhouette created by short-bodied waistcoats and leg-hugging breeches and pantaloons. Coats with tails replaced those with full skirts. Men stopped wearing the powdered wigs that their fathers had sported and went for the more natural look of their own hair, often cropped à la Titus to imitate the style of the Roman emperor of that name.

|

|

|

Not only were the silhouettes of the neoclassical style radically different; the types of fabrics changed, as well. During the eighteenth century, fabrics used in fashionable dress included opulent velvet, brocade, and damask that were often enhanced with floral designs. Silk was the most expensive material and was imported from Italy and France. Velvets and lace came from Italy, and linen from Germany and Holland. The fact that the gentlemen and ladies in the portraits on the Musgroves’ parlor walls wear brown velvet and blue satin indicates that they were very well to do. The term “velvet” refers to the weave of the fabric, not the fiber from which it is made. Often woven from silk, its short and dense pile has a shine that softly catches light. Since the production technique was time-consuming and complex, velvet was very expensive, available only to the extremely wealthy (Bucci). Like velvet, the term satin refers to the weave of the fabric, not the material. Usually made from silk, satin fabrics have a smooth and shiny surface. Due to the costly material, and the fact that it snags easily, it was worn only by the upper classes (Akou).

The Strong Family, by Charles Philips (1732). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Strong Family, by Charles Philips (1732). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As a result of the 1786 Anglo-French Treaty of Commerce, the British East India Company shipped huge quantities of cotton to France. Muslin, a lightweight cotton fabric of plain weave, began to surpass silk in popularity for fashionable dresses on the continent and in Britain, and it served the high-waisted and narrow neoclassical silhouette well. Greek and Roman sculptures were originally painted with bright colors, but the fact that they had been bleached over time led to the false notion that classical garb had been completely white (Tortora and Marcketti 311). Although ladies sometimes still wore silk, they heartily adopted white muslin for both day and evening wear. In men’s attire, practical materials such as unadorned wool, cotton, linen, and buckskin in subdued colors replaced bright colors, elaborate embroidery, and lavish fabrics. Akiko Fukai has commented, “If luxurious satin and velvet stood for the nobility and the old society of the eighteenth century, cotton symbolized the trend toward a new, more democratic, society” (111).9

The new fashions and furniture embraced by Henrietta and Louisa complement their unembarrassed and pleasant manners and the affability and cordiality of their family. Tony Tanner points out that, although the elder Musgroves “lack education and elegance . . . , it doesn’t matter. Because other values, such as friendship and hospitality, are coming to seem more important” (225). As Anne Elliot remarks, the Musgrove family members give “Uppercross its cheerful character” (P 133).

The good-spirited Musgrove daughters end up leaving the social class of the family behind: Henrietta marries a mere country curate, and Louisa enters the company of the meritocratic navy. Their clothing reflects the ideals of a more democratic society, and their additions to the parlor in the Great House create a cheerful and informal living space that encourages comfortable conversation. In Persuasion, generational change and happy domesticity usurp family history and tradition in importance. Austen shows that in order for alterations in furnishings and fashions to be true improvements, they must be undertaken in the spirit of friendliness and egalitarianism.

NOTES

1I would like to thank Ann Wass and Angela Tebbe Burke for their constructive comments during the development of this essay.

2The cottage was an architectural form that had traditionally been a habitation for the rural working poor but was currently in fashion as a dwelling for the wealthy. See Crowley’s chapter 7, “Picturesque Comfort: The Cottage” (203–29).

3.Mr. Knightley provides for the entertainment of Mr. Woodhouse during his visit to Donwell Abbey “[b]ooks of engravings, drawers of medals, cameos, corals, shells, and every other family collection within his cabinets” (393). My thanks to the anonymous reviewer of this essay for pointing out this connection.

4These rooms were arranged as a piano nobile (“noble floor” or “place of nobility”), while the ground floor was featured as a podium (platform level) or basement (Sharpe 112).

5The narrator describes this scene with gentle irony as a “fine family-piece” and Anne characterizes it as a “domestic hurricane.” The narrator observes: “Every body has their taste in noises as well as in other matters; and sounds are quite innoxious, or most distressing, by their sort rather than their quantity” (146).

6Georgians identified with the ancient world because they believed that their society had reached an identical pinnacle of cultural excellence. Edward Gibbon, in his The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1788), writes that contemporary Europe was “one great republic, whose various inhabitants have attained almost the same level of politeness and cultivation” (107).

7There have been few other periods in fashion history in which women have experienced such alterations in a single lifetime, such as the advent of short flapper dresses of the 1920s and the casual t-shirt and blue jeans of the 1960s (Kanai 118).

8In an 1811 beauty guide called The Mirror of the Graces, the expert does allow the use of rouge, because it restores the redness of the cheeks to those who have lost their natural color (41).

9Muslin might seem more democratic, but it was only relatively less expensive and easier to wash than silk, and so it was not something that the lower classes usually wore. Mrs. Musgrove comments about Mary’s nursery-maid, who must be wearing the latest style: “‘she is such a fine-dressing lady, that she is enough to ruin any servants she comes near’” (P 49). And, as Henry Tilney, a professed expert on muslin, remarks of Catherine Morland’s gown in Northanger Abbey, “‘I do not think it will wash well; I am afraid it will fray’” (21). The simplicity of muslin, more than the material itself, sets garments made of it apart from the luxuries of the old guard.

Corset (ca. 1780). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Corset (ca. 1780). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Panniers (ca. 1750). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Panniers (ca. 1750). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott, by Thomas Gainsborough (1778). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott, by Thomas Gainsborough (1778). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Suit (ca. 1760). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Suit (ca. 1760). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Dress (ca. 1807). © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Dress (ca. 1807). © Victoria and Albert Museum. “The Ladies Dress Maker,” from

“The Ladies Dress Maker,” from  Portrait of a Woman, by Sir William Beechey (ca. 1805). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Portrait of a Woman, by Sir William Beechey (ca. 1805). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and King of Hanover, after Thomas Rowlandson (1812). © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and King of Hanover, after Thomas Rowlandson (1812). © National Portrait Gallery, London. The Prince Regent, by Henry Bone after Sir Thomas Lawrence (1816). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Prince Regent, by Henry Bone after Sir Thomas Lawrence (1816). Metropolitan Museum of Art.