Readers of Jane Austen are intimately familiar with the passionate note Captain Wentworth writes to Anne Elliot at the climax of Persuasion. It’s a scene that captivates readers who, if they’re anything like me, enviously yearn for someone to scrawl in a frenzy of passion, “‘You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope’” (257–58). Yet, the conclusion to Jane Austen’s Persuasion as we know it was not the ending she originally penned. Austen rewrote the conclusion to Persuasion, relying on the incorporation of a miniature portrait to accomplish the reconciliation between Captain Wentworth and Anne Elliot. Benwick’s portrait not only propels the story to its turning point but also emphasizes the cultural shifts taking place in Regency England, articulating Austen’s complex attitude toward class restructuring in the early nineteenth century. Many critics claim that Austen revised her conclusion to make it more dramatic—her own nephew even going so far as to say, “She thought it tame and flat, and was desirous of producing something better” (Austen-Leigh 125). Regardless of the reason for the alteration, the inclusion of Benwick’s miniature portrait is a critical narrative instrument, connecting with wider practices in the visual arts that shaped cultural discourses on class fluidity, a central theme of this condition-of-England novel.

In chapter 11 of the second volume, Captain Harville shows Anne the miniature portrait Captain Benwick had commissioned for his first betrothed, Harville’s sister Frances, who died while Benwick was at sea. While in Bath, Harville has been tasked with getting a setting for the small painting for Benwick’s new intended, Louisa Musgrove:

“Look here,” said he, unfolding a parcel in his hand, and displaying a small miniature painting, “do you know who that is?”

“Certainly, Captain Benwick.”

“Yes, and you may guess who it is for. But (in a deep tone) it was not done for her. Miss Elliot, do you remember our walking together at Lyme, and grieving for him? I little thought then—but no matter. This was drawn at the Cape. He met with a clever young German artist at the Cape, and in compliance with a promise to my poor sister, sat to him, and was bringing it home for her. And I have now the charge of getting it properly set for another!” (252)

The ensuing discussion of the constancy of the sexes leads Anne to defend the fidelity of women and reveal that she still loves Captain Wentworth; overhearing her, Wentworth writes Anne a note confessing he still loves her, too, bringing about the conclusion of the novel. Benwick’s commissioning of a miniature portrait and its setting does more than facilitate the novel’s conclusion. It is a significant insertion for its art historical and sociocultural context, both as a reference to a period art form and as literary device that signals class ascendancy and fluidity.

Portrait of a Young Woman, thought to be Catherine Howard, by workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger (ca. 1540–1545). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Portrait of a Young Woman, thought to be Catherine Howard, by workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger (ca. 1540–1545). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The affiliation of miniature portraiture with aristocratic tradition makes it exceptionally important in the conclusion of Persuasion. Miniature portraiture is generally defined as a small-scale, portable image of an individual, typically a bust portrait placed in a decorative frame to be worn for public display or intimate viewing. Miniatures range in size according to the desires of the commissioner and the fashion of the time, varying from the miniscule to “too large to put in a pocket but small enough to be passed around a dinner table” (Pointon 48). Miniature portraits were made popular in England at the court of Henry VIII (1491–1547) with the influence of Burgundian and Flemish manuscript illuminations. Artists Hans Holbein (1497–1543) and Nicholas Hilliard (1557–1619) continued the tradition into the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and wearing miniatures as jewelry in the sixteenth century was a cultural practice of the elite, as seen in the Portrait of a Young Woman, Thought to be Catherine Howard. In this portrait, the subject wears luxurious garments and accessories associated with wealth: a French hood, gold jewelry, and a miniature portrait that mark her elevated social class.

Before the sixteenth century, miniaturists worked primarily on vellum, a material that allows paint to dry on the surface with a smooth, rich finish. As portraits on vellum gradually grew faint over time, the material was abandoned in favor of fired enamel and, later, ivory (Todd 77). While enamel had a richness of color, ivory was soft and gauzy but required a nimbleness of hand to avoid surface puddling of watercolor paint. The first painter to popularize ivory as a medium for miniature portraits was Bernard Lens (1682–1740), miniaturist to George I and George II.

Whether on vellum or ivory, miniature portraiture has a long history of association with aristocratic practices, confirmed both by the original miniatures and portraits that depict sitters wearing miniatures, which provide invaluable evidence of the tastes and aspirations of those portrayed. In the seventeenth century, commissioning a portrait of oneself was traditionally reserved for nobility, and wearing miniature portraits of other titled, esteemed family members or aristocratic or political figures in these portraits was a sign of familial relation or association and respect. Evidence of this fashion can be seen in the portraits of Katherine Manners (1623), an exceptionally wealthy aristocratic woman, and Princess Henrietta Anne of England, the youngest daughter of King Charles I.

|

|

|

In the seventeenth century, the aspiring pseudo-gentry and merchant classes commissioned and wore miniatures to elevate themselves socially, thereby conveying wealth and self-importance. By the time of Jane Austen’s lifetime, however, “anyone who possessed the means could acquire what had once been a mark of distinction” (Pointon 50). In 1777 William Combe wrote a book of poems in which he referenced prostitutes wearing miniature portraits: they consider “the Bracelet, with the Miniature-Painting, as an ornament necessary to [their] Station in Life” (qtd. in Pointon 50). While still a luxury good, miniatures, as Marcia Pointon argues, were cheapened by their appropriation by unseemly members of society (50).

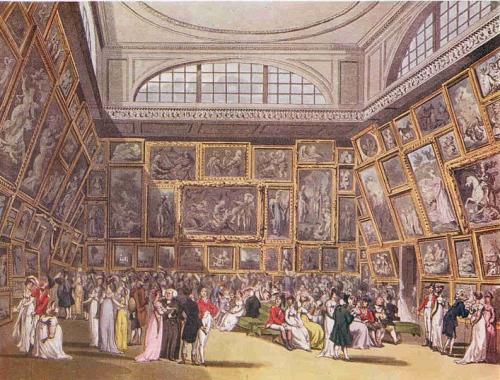

The shifting cultural perceptions of miniatures were further reflected in their treatment by the British Royal Academy. Established in 1769 as the “Royal Academy in London for the Purpose of Cultivating and Improving the Arts of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture,” the Royal Academy was the definitive authority on culturally acceptable and elite art in England, as an art school, exhibition space, authority on art, and institution charged with “elevating public taste” (“Britain’s Royal Academy”). When the Academy was founded in 1769, Nathaniel Hone (1718–1784) was the sole miniature painter to be made a member (Todd 77). Although exhibitions shown at the Academy included miniature portraits, they were often relegated to the downstairs in an institution where location was a direct statement about status within the art hierarchy. Miniatures were generally disliked by critics for their small size, perceived ease of completing, and commercialized status. Miniature painting was lucrative, and miniature painters profited from both patrician and middle-class patrons who, during the French and Napoleonic Wars, commissioned small portraits given to loved ones as tokens of remembrance, sometimes referred to as aides mémoires (Todd 78).

The Exhibition Room at Somerset House by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin (1808). The British Museum.

The Exhibition Room at Somerset House by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin (1808). The British Museum.

Portrait of Jane Austen’s Aunt, Philadelphia Hancock, by John Smart, Sr. Jane Austen’s House Museum, Jane Austen Memorial Trust.

Portrait of Jane Austen’s Aunt, Philadelphia Hancock, by John Smart, Sr. Jane Austen’s House Museum, Jane Austen Memorial Trust.

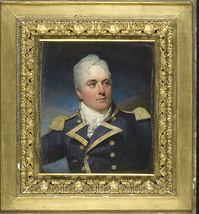

During the second half of the eighteenth century there was an insatiable market for miniatures. By the Regency, miniatures were an established practice of fashionable society, popular for their accessibility and charming intimacy. They were “the most likely pictorial artifact to be found in the bourgeois household” (Bertelson 351). One of the most popular artists of the time was John Smart (1742/43–1811), who painted “middle-class merchants, entrepreneurs, gentlemen makers of empire and professionals, their wives and relatives—including Jane Austen’s aunt Philadelphia Hancock” (Todd 78). Smart was famed for his ability to capture the lifelike character of those he painted with minimal decorative adornments; his delicate hand rendered almost translucent, porcelain-like images. Examples of Regency portraiture as seen in the miniature portraits of Captain Alexander Skene and of Captain Roger Curtis, R.N., convey the preference for naturalistic and delicate watercolor portraits. Naval officers often chose to be painted wearing their uniforms to indicate their rank and, therefore, status, within the Royal Navy.

|

|

|

Austen was familiar with the tangible and cultural practices of the visual arts and miniature portraiture; at one time, miniatures of members of the Austen family and their friends could be seen hanging in the dining room of Chawton Cottage (Bertelson 363). From her remaining correspondence, we know that Jane attended art exhibitions and would search for and assign portraits on display to the characters in her novels (24 May 1813).

Dining parlor (1990s). Jane Austen’s House Museum, Jane Austen Memorial Trust.

Dining parlor (1990s). Jane Austen’s House Museum, Jane Austen Memorial Trust.

Moreover, within her novels, she assigned artistic penchants to characters, including Elinor Dashwood, whose “drawings were affixed to the walls of their sitting room” (SS 30), and Emma Woodhouse, who displayed her “beginnings,” including “[m]iniatures, half-lengths, whole-lengths, pencil, crayon, and water-colours,” which “had been all tried in turn” (E 45). Austen uses art within her novels to move the plot and to distinguish her characters. In Sense and Sensibility Elinor Dashwood’s hopes are shattered when Lucy Steele unveils her miniature of Edward Ferrars, confirming their engagement (151). In Mansfield Park Fanny Price has “a collection of family profiles, thought unworthy of being anywhere else” in her room (179); and in Pride and Prejudice Elizabeth Bennet on her trip to Pemberley with the Gardiners views “the likeness of Mr. Wickham suspended, amongst several other miniatures, over the mantelpiece” in addition to a miniature portrait of Mr. Darcy, “‘and very like him’” (273).1

In her conclusion to Persuasion Austen uses the miniature portrait of a sailor for the first and only time. While naval officers’ promotions, earned wealth, and marriages into esteemed British families are manifestations of class struggle in the writing of Jane Austen, Benwick’s miniature portrait serves as a manifestation of the anxieties felt by the aristocracy and the up-and-coming-military meritocracy.

As confirmed by the memoir of Royal Navy Captain Thomas Boulden Thompson, men employed in service to the British Royal Navy often carried miniatures with them. In the account of the capture of the 50-gun British ship Leander by the French Généreux in 1798 (Robson 60), Captain Thompson describes the treatment of British on board the French vessel, led by Monsieur Lejoille, as “infamous.” The British were “plundered of everything they possessed,” Captain Thompson robbed of a miniature of his mother (“Biographical Memoir”).

Like the miniatures of family and friends they carried in pockets and personal seabags, sailors commissioned miniatures of themselves as tokens for those who remained on land. A naval miniature portrait, such as that done by “‘a clever young German artist at the Cape’” for Benwick (P 252), was a frequent commission, and such a practice was common among Austen’s contemporaries as evidenced by the numerous military miniature portraits preserved in museums.

In Persuasion, Austen emphasizes sailors’ challenge to the traditional British class structure as members of the Royal Navy gained what Sir Walter calls “‘undue distinction’” through advancing rank and acts of merit rather than birth into a prominent family (21). The Royal Navy was a comfortable subject for Austen, who grew up in the village of Steventon and later lived in Chawton, both in the county of Hampshire, the site of Her Majesty’s Naval Base Portsmouth. Two of Jane’s six brothers, Francis (1774–1865) and Charles (1779–1852), were sailors in the Royal Navy. Francis actively served from 1786 to 1865, retiring at the rank of Senior Admiral of the Fleet, aged ninetey-one; Charles served from 1791 to 1811 and again from 1826 to 1852, when he died of cholera at the age of seventy-three “in the line of duty” at the rank of Rear Admiral (Southam 39). Both Francis and Charles commissioned miniature portraits while in the service. Included here are the miniatures of Francis Austen, taken in his twenty-second year while in service to the Navy, and Charles Austen, later in his career. Francis’s miniature, commissioned during his sister’s lifetime, may have influenced the inclusion of Benwick’s in Persuasion.

|

|

|

During Austen’s lifetime, the Royal Navy was the largest and most powerful military force in the world, integral to securing Britain’s enduring global economic dominance, “based on free access to global trade routes, guaranteed by strategic positions and the Royal Navy” during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (Robson 233).2 Sailors played a critical role in maintaining British global influence, aboard ships that both defended British trade from potential threats and aimed offensive charges at ships that dared challenge them. The prominence of the Royal Navy led many young men to join, as a number of Austen’s characters do. Those afforded little opportunity for economic advancement on land were incentivized to join the navy, which afforded officers aboard ship greater opportunity to earn wealth and status through the acquisition of prize monies, earned by capturing enemy ships or valuable cargo. When an enemy ship was sunk, each crewmember of the conquering ship was given a portion of “Head Money,” a reward calculated by a tally of men on the enemy ship, at £5 per man (Harris 82). Sinking a ship, however, was hardly as lucrative as capturing an enemy ship. In the case of a capture, the conquered ship could in turn be purchased by the Admiralty for a higher payout to officers, particularly if the captured ship was carrying profitable cargo (82). Wentworth returns from the war with “five-and-twenty thousand pounds” (P 270), a sum “something like £1.25 million in modern terms” (Le Faye, World 287).3

The accumulation of great wealth by sailors was not, of course, the case for all, as Austen shows us in Persuasion with the less fortunate Harville family. Captain Harville, recovering from injuries sustained in the war and at home on half-pay with a wife and children, resides in Lyme Regis, in a house with “rooms so small as none but those who invite from the heart could think capable of accomodating so many,” with “ingenious contrivances and nice arrangements” that made up for the purported “deficiencies of lodging-house furniture” (106).4

Though the Harvilles had no such good fortune, a naval career did make possible the accrual of wealth and rank outside the establishment of inherited wealth and status, a point critical to the transformation of the upper classes in Regency England. Sailors of modest birth like Captain Wentworth and Admiral Croft garnered distinction on the decks of their ships rather than through ancestral lands and estates. While members of the navy may not have been accepted into the circles of those families of old, established money, some naval officers were able to earn wealth comparable to that of the landed gentry—and achieve land ownership. It was historic reality, rather than fictional coincidence, that Mr. Shepherd suggests that Sir Walter economize by renting his large estate to a wealthy naval officer.5

Captain Benwick then becomes an important part of the discussion about the dichotomy of wealth in the Regency, particularly as concerns the miniature portrait. Captain Benwick, “first lieutenant of the Laconia, . . . an excellent young man and an officer” (P 104) seems to be of the middle classes. When we are introduced to him in Lyme Regis, he is mourning the loss of Fanny Harville and staying with her family, “living with them entirely” (104). He is described by Mary Musgrove as “‘not at all a well-bred young man’” (143), a description which may refer to his lack of deference to Mary’s right to precedent. Benwick, however, is a man of some means. His fortune earned on the high seas is described as “great” (104) but not more than Wentworth’s, according to Mary, who finds “it was very agreeable that Captain Wentworth should be a richer man than either Captain Benwick or Charles Hayter” (272). Charles Hayter is positioned to take over as the curate of the aging Dr. Shirley, likely receiving a salary of something like £50 a year (Collins 111)—though he is set to inherit “‘the estate at Winthrop, . . . not less than two hundred and fifty acres’” (P 82). Benwick’s income is placed between Hayter’s current £50 and Wentworth’s annual income of £1,250 (Francus).

As the first lieutenant of the Laconia, a sixth rate ship, Benwick’s position in 1815 would have garnered £8.8 per month, about £100 per year (O’Neill 73).6 He was later promoted to captain, a position that would have earned £16.6 per month, about £200 per year (73). Benwick is not impoverished: £200 per annum in addition to a lump sum of prize money would make Benwick a decent catch during wartime. While the amount of Louisa Musgrove’s dowry is never explicitly stated, the Musgroves are said to be “in the first class of society in the country” (P 80), with “landed property and general importance” (31). Even the snobbish Mary Musgrove concedes that Benwick is “‘[c]ertainly not a great match for Louisa Musgrove, but a million times better than marrying among the Hayters’” (179). We can safely place Captain Benwick, having earned his fortune through the navy, as a man of some means, with purchasing power.

The ordering of a miniature portrait by an essentially self-made man is a transgressive act and a signal to Austen’s readers of the kind of cultural negotiations that were occurring during the Regency Originally a cultural practice of the elite, miniatures—both as personal mementos and markers of collective social identity—provide cultural insight into the permeability of the social and class boundaries of the period. Benwick’s profession is not approved of by Sir Walter, who, representative of the struggling landed gentry, says, “‘The profession has its utility, but I should be sorry to see any friend of mine belonging to it’” (21). It affords Benwick the leverage to participate in a cultural practice belonging, in a previous time, to the genteel. The clash between those who earned their wealth and those who inherited it is a recurrent theme throughout this novel, as seen in Sir Walter Elliot’s open disdain for the navy, the weight afforded to rank both in high society and the Royal Navy, and Austen’s pointed use of Debrett’s Baronetage of England and navy lists. Class relations are paramount to Persuasion, and tension among the classes was particularly resonant in the visual arts of the period, which convey material manifestations of personal wealth.

Art makes repeated appearances throughout Persuasion as a marker of class distinction. In chapter 3, Mrs. Clay arguing for the decency of officers who might lease Kellynch Hall says, “‘I have known a good deal of the profession; and besides their liberality, they are so neat and careful in all their ways! These valuable pictures of yours, Sir Walter, if you chose to leave them, would be perfectly safe’” (20). Anne, preparing to leave Kellynch, copyies “‘the catalogue of [her] father’s . . . pictures’” (41) likely large, expensive oil on canvas works passed down through generations, appropriate for the furnishing of a great house like Kellynch.

Austen uses art owned by her wealthy characters as indicative of fortune and status, as seen in Pride and Prejudice when Elizabeth Bennet tours the “picture-gallery” with “many family portraits” at Pemberley (276–77). In Sense and Sensibility with the announcement of Willoughby’s marriage to the excessively wealthy Miss Grey, Mrs. Palmer busies herself with “procuring all the particulars in her power of the approaching marriage. . . . She could soon tell at what coachmaker’s the new carriage was building, by what painter Mr. Willoughby’s portrait was drawn, and at what warehouse Miss Grey’s clothes might be seen” (244). Austen uses the wedding portrait—classed with the new carriage and new clothes—as an indication of Miss Grey’s wealth. Commissioning wedding portraits of a bride and groom was a traditional practice of the aristocracy: here it serves as a pointed demonstration of the power of Miss Grey’s £50,000.

In contrast, the home of the Harvilles is described in detail, but there is no reference to any art hanging on their walls. In volume 2, chapter 2, Admiral Croft “stand[s] by himself, at a printshop window, with his hands behind him, in earnest contemplation of some print” of a ship (183). The admiral’s appreciation of prints, a popular and inexpensive art form widely reproduced and circulated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, is another pointed juxtaposition Austen uses to reveal class disparities. While members of the landed classes have grandiose collections of fine paintings, the middling class is shown to take enjoyment in more common, modest manifestations of art.

The inclusion of Benwick’s miniature in the climactic scene of Persuasion is an indication of the transformation in society and the challenges posed by this transformation. This revised version of Jane Austen’s conclusion to Persuasion emphasizes her acknowledgement of the mounting social conflict occurring at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. As a meritocratic institution, the Royal Navy allowed for socioeconomic promotion and buying power. Given the implied status associated with miniatures, the ability to commission these portraits evinces sailors’ increasing affluence and upward mobility during the Napoleonic Wars.

Benwick’s commissioning of a miniature indicates his desire to emulate the sophistication and wealth of the aristocracy; his fiscal ability to do so signals his class ascendancy and the transformation in the socioeconomic dynamics of British society. Jane Austen’s deliberate use of the miniature in the conclusion of Persuasion demonstrates her observation of society and perhaps signals her recognition of class fragility in a social order that was (pardon the pun) adrift.

NOTES

1Jane mentions miniatures in a letter written to her nephew James Edward Austen on her forty-first and final birthday in December of 1816 in reference to her own art: “What should I do with your strong, manly, spirited Sketches, full of Variety & Glow?—How could I possibly join them on the little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory on which I work with so fine a Brush, as produces little effect after much labour?” (16–17 December 1816).

2The Navy was paramount to insurance of continued remunerative British import and export trades: in 1793, British imports were valued at £19.3 million and exports at £20.4 million. By 1814, this had ballooned to £80.8 million in imports and £70.3 million in exports (Robson 233). The astounding influence and economic dominance of Britain was threatened by the French. And while the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar affirmed Britain’s superior naval power, British policy after 1805 aimed to curtail the war with Napoleonic France “in a manner that was most beneficial to British interests” (Robson 234).

3Jane Austen was familiar with sailors’ aspirations for a great capture, as her own brother Francis Austen waited two years, from 1804 to 1806, before earning “honours and prize-money [that] evidently encouraged him to think that he could now afford to marry” (Le Faye, Family Record 153).

4Lyme was described in an early-nineteenth-century guidebook as “a retired spot. . . . [L]odgings and boarding at Lyme are not merely reasonable, they are even cheap; [with] amusements for the healthy, and accommodations for the sick.” It was an appropriate location then for Captain Harville and his family (qtd. in Le Faye, World 288).

5Indeed, the single most famous sailor of the Royal Navy, Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), was the son of a poor village rector. Nelson joined the navy at the age of twelve and rose through the ranks through courageous acts and distinction by influential members of the Royal Navy.

6Due to time constraints, my research has produced only pay rates for 1815, after the setting of Persuasion.

Portrait of Katherine Manners, after Anthony van Dyck (ca. 1623). National Library of Wales.

Portrait of Katherine Manners, after Anthony van Dyck (ca. 1623). National Library of Wales. Portrait of Princess Henrietta Anne of England, by Jan Mytens (ca. 1665). Enfield Museum Service.

Portrait of Princess Henrietta Anne of England, by Jan Mytens (ca. 1665). Enfield Museum Service. Miniature portrait of Captain Alexander Skene, by Andrew Robertson (1805). Victoria and Albert Museum.

Miniature portrait of Captain Alexander Skene, by Andrew Robertson (1805). Victoria and Albert Museum. Portrait of Captain Roger Curtis, R.N., by George Engleheart (1811). Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Portrait of Captain Roger Curtis, R.N., by George Engleheart (1811). Philadelphia Museum of Art. Miniature of Francis Austen, by unknown artist (1796). Jane Austen’s House Museum, Jane Austen Memorial Trust.

Miniature of Francis Austen, by unknown artist (1796). Jane Austen’s House Museum, Jane Austen Memorial Trust. Miniature of Charles Austen, by unknown artist. Jane Austen’s House Museum, Jane Austen Memorial Trust.

Miniature of Charles Austen, by unknown artist. Jane Austen’s House Museum, Jane Austen Memorial Trust.