With its stunning mountain scenery and full production of the musical An Accident at Lyme, as well as with its speakers and special ambiance, I can claim that the Lake Louise AGM on Persuasion was indeed historic. Of course all our AGMs are historic, but I like to think that some are more historic than others!

First, some back-story.

In 1975, before the birth of JASNA, I convened a Jane Austen conference at my University of Alberta to celebrate the bicentenary—not of Austen’s death, or the publication of her novels, as we have been doing recently—but of her birth. We had a splendid array of speakers—Lionel Trilling, Barbara Hardy, A. Walton Litz, Norman Page—the biggest names of the day.1 And there I first met J. David Grey—or Jack, as we all came to know him. Jack was the most gracious of conference delegates. On that occasion he got talking to Henry Burke. Joan Austen-Leigh was there too (Austen-Leigh, “Founding” 8). She and Jack had already met in Chawton, earlier in the summer, and had mooted the possibility of a North American society—as Devoney Looser told us in her talk at Huntington Beach (140–43). And bingo! There at my conference we had our triumvirate of founders. I’m proud to have had that much hand in the creation of JASNA.

In organizing that long-ago bicentenary conference I got to know our British speakers, Barbara Hardy and Brian Southam. Brian invited me to give the address at the 1977 meeting of the Jane Austen Society, performing in that “famous tent on the grounds of Chawton House,” as Joan put it.2 JASNA was yet to be born, but JAS, you might say, was already set in its ways, with an annual swift business meeting followed by a single talk, on a July afternoon, with tea afterwards on the lawn of Chawton House. For the occasion my husband, Rowland, and I and the kids stayed with a friend nearby, Ruth Robbins of Rookery Farm in Kingsley, who was a member of the JAS Committee. Rawdon and Lindsey, then seven and five, delighted in watching their marbles roll down the sloping floor of her beautiful Tudor farmhouse. Ruth arranged for a sitter while Rowland and I went to lunch with Sir Hugh3 and Lady Smiley, before my talk.4 It was a stirring contact with an earlier era. On the wall was a portrait of Lady Smiley in her youth, by Augustus John. At lunch I sat next to Austen’s early biographer, Elizabeth Jenkins, who was in her nineties at the time. She chatted familiarly of Virginia Woolf and felt “Virginia” made an undue fuss, at the dances they both attended, about the fact that it’s only the man who can take the initiative in seeking a partner. Trust “Virginia”!

Following my 1975 conference and the founders’ consultations, Jack did busy correspondence in that amazing spidery handwriting of his, on his distinctive Janeite stationery. A bunch of scholars were listed there as “Patrons”—to give credibility to “an extremely shaky enterprise,” writes Joan (“Founding” 9). I believe they were largely drawn from the participants in my 1975 conference. And on that further historic occasion of 1979 at the Gramercy Park Hotel in New York, JASNA launched its inaugural AGM. Walton Litz was again a speaker.

Jack was a very special guy. Like all of us, he was devoted to Jane Austen, and he was also a highly knowledgeable collector. There was something princely about him. Like Jane Austen’s favorite hero, Sir Charles Grandison, he was magnanimous. He would always do more than was asked of him—give more, laugh more, enjoy more. Ask him for a dime, you’d get a treasure—whether in money, or gifts, or just grand, generous thinking.

Come to think of it, magnanimity seems to characterize committed Janeites. Joan Austen-Leigh donated the precious Jane Austen writing desk she had inherited to the British Library—and if that isn’t magnanimous, I don’t know what is! The story of Alberta Burke and the lock of hair has gained mythic status. A dedicated collector of Austen memorabilia, she purchased a lock of Jane Austen’s hair through Sotheby’s. At an early meeting of the Jane Austen Society, and hearing Brit mutterings about rich Americans who snatch treasured British relics and take them away to America, she simply announced that she would give the lock to the Society. Such spontaneous generosity is confounding. Juliette Wells gives the full story, from Henry Burke’s narration (54–55).

Jack engaged us all in Jane Austen projects. At a time when our neighbor planet Venus was being mapped, he sought my support in getting Austen’s name on a geographical feature; he was in pursuit of an extraterrestrial reputation for her! And sure enough, there’s a Jane Austen Crater on Venus. Another project he involved me in was the design of a deck of cards in which Darcy, Elizabeth, Wentworth, Anne, Marianne, and the rest would replace the picture cards as kings and queens and jacks.

J. David Grey by Juliet McMaster

J. David Grey by Juliet McMaster

I must pause over another AGM Jack organized, again in his beloved New York City: 1987, at the Waldorf Astoria, on “The Juvenilia and Lady Susan.” He loved the juvenilia. He used to say that two people produced world-class art before they reached adulthood: Jane Austen and Mozart. (You will know that I agree with him!) Sir Hugh and Lady Smiley graced that occasion with their presence. I was on a panel with Jan Fergus, and we became lasting friends. There Jack first encouraged people to come in Regency dress, and that’s when I first decided to go as a guy. I don’t have the endowment to look good in an Empire-line dress. But I did fancy those Regency cut-away jackets, and our Drama Department was ready to tog me out. As I walked down the mirror-lined walls of the Waldorf, I was so confounded by the many reflections of me in that outfit that I had to dash back to fortify myself with a gulp of Scotch. (The Scotch came in handy later that night, when Jack and his co-organizer Susan Schwarz came by to gossip and relax.) “Oh Juliet!” Jack reproached me in dismay when I arrived. “I have a prize for the best-dressed woman and a prize for the best-dressed man. But I have nothing for the transvestites!” It was typical of him that he had bought prizes. He loved giving presents, and he was good at it.

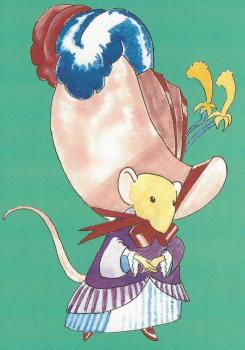

There too I was first smitten with Jane Austen’s cheeky tale “The Beautifull Cassandra,” about a girl who falls in love with a bonnet, and conceived the idea of making it into a picture book for children, with the characters turned into small animals. Jack loved the idea. It took me long to find a publisher. But when the press asked me to suggest a reader, of course I named him. Characteristically, he turned to his five-year-old niece and read her the story and showed her the pictures. What was her verdict? She said, “I want a bonnet!” I couldn’t have had a more authoritative response. This was a book for kids, after all. And with help from JASNA my book went to press.

|

|

|

Another piece of the back-story: My friend and colleague Bruce Stovel attended his first AGM with Rowland and me two years later, in 1989, at Santa Fé. From that day he was a goner for AGMs. I recall that we both bought our sons ponchos in Santa Fé. Bruce and I—and Bruce’s Nora, and my Rowland—talked AGMs, and in due course both our spouses became Janeites, perhaps in self-defense!5 Bruce was keen to do our own AGM, but Edmonton, our city, isn’t exactly an irresistible tourist resort. We wanted a beautiful setting. Lake Louise, “the Jewel of the Rockies,” had to be it. At the exclusive Chateau Lake Louise, no less. We put the idea to JASNA, and JASNA went for it. (There was less palava on such matters in those days.) Everyone on the Board recognized what a spectacular event it could be. Whether the membership would flock there was yet to be seen.

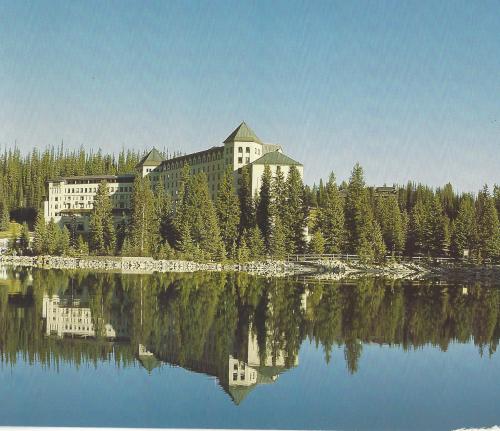

Chateau Lake Louise

Chateau Lake Louise

And in fact there were major disadvantages. Lake Louise is high up in the Canadian Rockies, and winter can descend early. Besides the Chateau and some other hotels, the township is a mere village—some 120 miles from the nearest international airport, Calgary, and 300 from our own Edmonton. It could be a logistical nightmare. Would people take the trouble to come at all, given the travel problems, the risky weather conditions? If the block of rooms we booked at the Chateau didn’t fill up, Bruce and I would be personally responsible for the shortfall. But—in some fear and trembling—we went ahead.

We needn’t have worried. People couldn’t resist that setting. The rooms filled up, to the maximum of 600, which was by far the biggest AGM attendance so far in JASNA’s history. Our earliest booking was from Jack Grey. As soon as reservations opened, he booked a whole suite at the Chateau Lake Louise. It was an act of faith, because he had already received the cancer diagnosis. But that grand early booking was a great confidence-builder for us organizers.

Alas, Jack never occupied that suite, nor saw the stunning view that it commanded. He died in March of that year. He was on the program, though. We had a memorial for him, and the conference was dedicated to his memory.

Joan Austen-Leigh

Joan Austen-Leigh

Joan Austen-Leigh was there, however, and she spoke movingly of Jack at the Memorial. Joan too was a good friend. (I was honored to be introduced, when I gave this talk in Kansas City, by Joan’s daughter Freydis Welland.) Another bicentenary conference of 1975 was held in Joan’s home city of Victoria, British Columbia, and there I first attended her play Our Own Particular Jane. I enjoyed her novels Stephanie and Stephanie at War. When she sent me the manuscript of Mrs. Goddard, Mistress of a School, a most engaging spin-off of Emma, I provided detailed commentary and some suggestions. On the strength of those, some of which she adopted, she waived a royalty for our Edmonton production of Our Own Particular Jane. This was in 1992, the lead-up year to our Lake Louise AGM. “Such anticipation!” she wrote, in a letter I keep in my inscribed copy of Mrs. Goddard. “You’re going to have the whole world there.” Bruce and I had the founders on our side.

At Lake Louise, though, Joan was a rather sad presence. She was grieving for Jack. I somehow felt that she and Jack came to look at JASNA rather as Frankenstein looked at his monster—with a certain awe, as at a creature that had gathered an unpredictable and possibly destructive momentum of its own. I spoke to her as she lingered by that beautiful lake, which she wouldn’t leave to attend the next program event. She lamented what she called the “academic” cast of the papers presented and would have liked the more popular and intimate tone she had favored as the editor of Persuasions. (It was she, of course, who chose our journal’s title and who edited it for the first eight years.) She was an “amateur” in the best traditional sense—the sense that makes “professional” sound second-rate.6

So much for the back-story.

A word about funding. Being academics in the English Department, Bruce and I applied for grants, from our university and from Canada’s granting agency for the humanities.7 Our location involved extra costs: for instance, since it was so far from our homes, during site visits all committee members and others involved had to be accommodated at the Chateau, which isn’t cheap, and their travel paid for. To a large extent we chose graduate students to help us: to do the huge work of registration, hotel arrangements, and so on. A student in Art and Design created our logo. The involvement of students not only helped us get the grant; it gave them excellent experience and considerably lowered the average age of our attendees!

A word about funding. Being academics in the English Department, Bruce and I applied for grants, from our university and from Canada’s granting agency for the humanities.7 Our location involved extra costs: for instance, since it was so far from our homes, during site visits all committee members and others involved had to be accommodated at the Chateau, which isn’t cheap, and their travel paid for. To a large extent we chose graduate students to help us: to do the huge work of registration, hotel arrangements, and so on. A student in Art and Design created our logo. The involvement of students not only helped us get the grant; it gave them excellent experience and considerably lowered the average age of our attendees!

What should we pay our plenary speakers, prominent scholars all? We had novelist Margaret Drabble from England; the feminist critic Elaine Showalter from Princeton; and our own Isobel Grundy, Tory Professor in our own Department. They all got expenses, of course, and to Maggie and Elaine we offered a $1000 honorarium. And here’s how cheese-paring we thought we had to be: we asked Isobel if she would be prepared to speak without honorarium—unless and until we made a profit. Isobel, being Isobel, cheerfully agreed. (Her paper, characteristically, was called “Persuasion: The Triumph of Cheerfulness”!) I’m glad to say that when we made that profit, the $1000 came as a bit of serendipity to her.

The grant also enabled us to do what only two other AGMs have done: waive the registration fee for breakout speakers. I rather wish that JASNA AGMs would do that again, at least for the speakers who apply for it. It seems little enough to do for those who so inform and entertain us.

Bruce and I, as English profs, had a network of colleagues and graduate students to draw upon for support, but at that time Edmonton had no local branch of JASNA. Clearly we needed one, and the AGM gave us the occasion to swing into creating one, and we did. It is still flourishing, with monthly or bi-monthly meetings from fall to spring, a wonderfully lively and energetic community. We would have organized the 2018 AGM if we could!

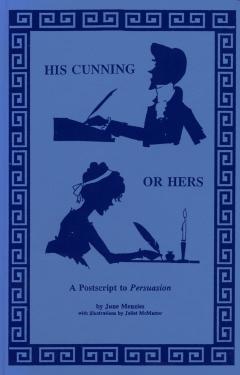

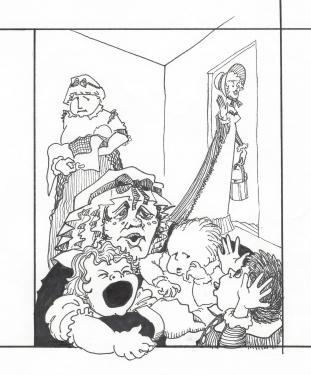

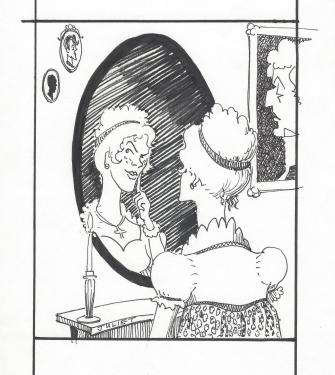

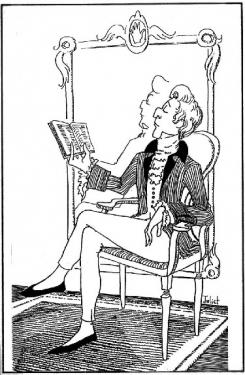

Of course, like other AGM conveners, we wanted our AGM to be special, even besides the spectacular scenery. One special feature was to be our very own Persuasion spin-off. June Menzies of our local chapter took on the writing of it. It was an epistolary fiction, consisting of letters pertaining to that clandestine relation between Mrs. Clay and William Elliot, called His Cunning or Hers. Mrs. Clay’s main correspondent is her long-suffering sister Adelaide, stuck minding the children while Penelope slopes off to catch herself a baronet. William Elliot’s main correspondent is Colonel Wallis. June captured the period style very well; for authenticity she studied and quoted the Bath Chronicle of the day. And I became the illustrator. I posed my Sir Walter by a mirror.

|

|

It’s intriguing to follow the familiar action of Persuasion from this different point of view. For instance, when Sir Walter delivers his diatribe against Mrs. Smith—“‘A poor widow, barely able to live, between thirty and forty—a mere Mrs. Smith, an every day Mrs. Smith’” (P 158)—Mrs. Clay applies it to herself:

It might just as readily have been “a mere Mrs. Clay, an everyday Mrs. Clay.” Secretly mortified, I hastened out of the room. As I sat at my dressing-table looking at my reflection in the glass I was forced to admit to myself the precarious nature of my previous ambitions—ambitions which perhaps now may be redirected? (Menzies 32).

She ponders Sir Walter’s portrait on one side, a miniature of William Elliot on the left. Don’t miss the freckles!8

|

|

Besides His Cunning or Hers, we devised other gifts for our delegates: our conference folder was a veritable Christmas stocking of goodies! It included extracts from the Baronetage and the Navy List and a postcard of the Cobb at Lyme, with the quotation from Tennyson when he visited Lyme in 1867: “Now take me to the Cobb and show me where Louisa Musgrove fell” (372–73). There was a map of local hikes; a package of seeds of mountain wildflowers; and a “medicine stone,” a good-luck pebble, with icons of frog and bear and beaver by local indigenous artists. These images became another motif for our design, for instance in the banquet menu. And animals were indeed part of the fun of our conference. We were in a National Park, after all. Ed Copeland was delighted to watch a bear with two cubs climbing a tree. And when Elaine Showalter reviewed the AGM for TLS, she couldn’t resist mentioning “the coyote and rutting bull elk”9 that she and other delegates watched from the bus between Calgary and Lake Louise!

Besides His Cunning or Hers, we devised other gifts for our delegates: our conference folder was a veritable Christmas stocking of goodies! It included extracts from the Baronetage and the Navy List and a postcard of the Cobb at Lyme, with the quotation from Tennyson when he visited Lyme in 1867: “Now take me to the Cobb and show me where Louisa Musgrove fell” (372–73). There was a map of local hikes; a package of seeds of mountain wildflowers; and a “medicine stone,” a good-luck pebble, with icons of frog and bear and beaver by local indigenous artists. These images became another motif for our design, for instance in the banquet menu. And animals were indeed part of the fun of our conference. We were in a National Park, after all. Ed Copeland was delighted to watch a bear with two cubs climbing a tree. And when Elaine Showalter reviewed the AGM for TLS, she couldn’t resist mentioning “the coyote and rutting bull elk”9 that she and other delegates watched from the bus between Calgary and Lake Louise!

Paula Schwartz

Paula Schwartz

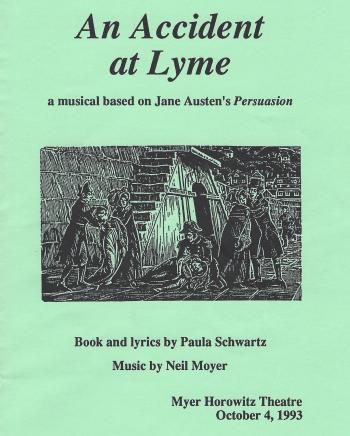

Another special feature of our AGM was the musical An Accident at Lyme, by Paula Schwartz, a beloved JASNA member who is no longer with us. (She wrote her Harlequin romances under the name of Elizabeth Mansfield.) There had been a concert version of her musical Elinor and Marianne at the Washington, D.C. AGM of 1990. But we were to present a full production, costumes and all, with a four-piece orchestra.10 The director, well known in Edmonton’s Citadel Theatre, was Stephen Heatley, now Chair of Drama at the University of British Columbia. To my delight he cast my daughter-in-law, Gail Sobat, a soprano, as Anne Elliot. Cast and musicians had to do all rehearsals in Edmonton, and they all had to be transported to Lake Louise and accommodated there. Of course Bruce and I fully involved ourselves in the rehearsals, which were a great builder of excitement.

The Friends of the University of Alberta were willing to supply a grant towards costs, but they stipulated that for the benefit of our students at home there had to be a performance in Edmonton before we headed for Lake Louise. Paula Schwartz was not about to miss the world première of her musical, so she came to us early, and we all delighted in the first performance. She and her husband, Ira, drove with Rowland and me to Lake Louise the next day.

This was the Wednesday before the official AGM opening on Friday. As we drove and gained altitude, the clouds gathered above us. Soon it was raining. Then it was snowing. Seriously! By the time we got to the Chateau there were several inches. It augured not well!

Thursday was for registration, and the troops came early. The snow had stopped, but a fog descended. You couldn’t see there was a lake outside the window, never mind mountains beyond it. Sandy Lerner registered that day. She had recently signed a long-term lease of Chawton House, and her name was much in the news. I persuaded her to come by asking her to introduce Isobel Grundy. Isobel had given Sandy invaluable advice on the books to purchase for her library of early women’s writing in English. When Sandy introduced Isobel she said, “I worship this woman.” Nobody knows more about early women writers than Isobel!

Sandy Lerner (on left) and

Sandy Lerner (on left) and

Garnet Bass - JASNA President (on right)

Swathed in fog, with no advertised panoramas visible, we chewed our fingernails and hoped—as more and more delegates arrived and looked for the view that wasn’t there. What if it never appeared?

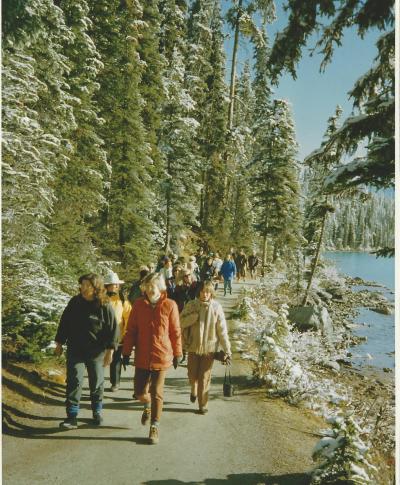

Rowland and I had a room at a corner of the Chateau, overlooking the lake. I got up early on Friday and looked out. Halleluia! Clear sky, Mt. Victoria resplendently visible and gleaming with the new snow. I am not a religious woman, but right away I was down on my knees, thanking God for that magnificent weather, which remained for the duration. On our hike that morning we found that the snow had thoughtfully withdrawn from the trail but remained picturesquely in the trees.

Friday Hike

Friday Hike

As for that other problem, the logistics of getting people to the Chateau: Bruce arranged for a special gathering room in Calgary airport and a succession of chartered buses. He himself drove the cast of An Accident at Lyme. It was rumored that Bruce had cloned himself, since there were confirmed sightings of him at several different locations simultaneously—and always where he was most needed.

On that Friday morning we hiked to Lefroy Hut, just under Mt. Lefroy—which was named after a grandson of Jane Austen’s friend Mrs. Lefroy.11 The Canadian painter Lawren Harris, one of our renowned Group of Seven, painted Mt. Lefroy in 1930, and his painting is now famous. Helen Lefroy from England, a descendant of the same family, was among us hikers. When I introduced her at Lefroy Hut, they gave her lunch on the house.

Also on Friday were two performances of An Accident at Lyme (no extra cost). Paula Schwartz had included Jane Austen herself as a character in the script—an author in search of a heroine—and there are poignant exchanges as she and Anne work out Anne’s character and destiny. A shot of the cast below shows Anne and Wentworth at the back on the left, with Sir Walter nearby.

Cast of An Accident at Lyme

Cast of An Accident at Lyme

Musical numbers included a duet between Charles and Mary Musgrove, “We might pass for a happy couple” (Schwartz 1.4), and an engaging company number at the concert in Bath, when Anne hopes Wentworth will return to sit by her, “An empty seat beside me.” It turns out that all the characters have their secret longings. Sir Walter sings wistfully,

Perhaps we’ll be lucky

And Lady Dalrymple

Will sit down beside me

And ask us to tea. (2.3)

As Anne begins to understand Wentworth’s returning love and his jealousy of William Elliot, in the novel we read, “The gratification was exquisite. But . . . it was misery to think of Mr. Elliot’s attentions” (191). In the musical such opposed emotions are captured in Anne and Wentworth’s duet, “Between despair and delight” (2.3). Paula Schwartz is a close reader and a sensitive adapter.

The lasting content of an AGM is supplied by the speakers, and ours lived up to the standard of the scenery and other accoutrements.

Margaret Drabble

Margaret Drabble

Margaret Drabble indulged us with her own fictional Persuasion update, based on the assumption that Elizabeth Bennet wasn’t just joking when she said she fell in love with Darcy after seeing Pemberley. Drabble’s modern-day heroine is similarly smitten by an estate: the Dower House at Kellynch, now neglected and moldering, like the latter-day baronets who inherit it. But this self-confessed lower-middle-class narrator responds to the faded glory of the crumbling estate and finds the waft of decay irresistibly erotic. She is attracted by the reigning baronet, Bill Elliot. “He is good-looking,” she notes. “The Elliots are famed for their good looks” (209). Sound familiar? Sir Walter would be proud. But like Mrs. Clay Drabble’s heroine hesitates between the reigning baronet and his heir. Along with the late-twentieth-century vision of Kellynch and its people comes a delicious referentiality to Jane Austen’s novel that captivated the audience. Soon after “some early Elliot had been obliged to let the hall” (that would be Sir Walter), we hear, “There had been a scandalous liaison round the time of Waterloo which had scattered illegitimate children all through the county” (207). That would be Sir William Elliot!

Drabble’s heroine is named Emma Watson—of course recalling the heroine of Austen’s unfinished novel The Watsons. Drabble was not to know that today’s famous Emma Watson is the young actress who plays Hermione in the Harry Potter movies. So the whirligigs of time connect Austen’s early nineteenth-century novel with Drabble’s late-twentieth-century fiction, and on to our present early twenty-first-century movies.

Isobel Grundy

Isobel Grundy

Isobel Grundy’s “Persuasion: The Triumph of Cheerfulness” reminds us that alongside Anne’s emotional pain is a tough resilience, her staunch capacity to be amused. Austen, Grundy suggests, was contesting the claims of her contemporary Anna Laetitia Barbauld, collector of the British Novelists volumes of 1810, that women lack humor, specialize in sensibility, and leave “the brisker flow of ideas . . . to the stronger powers of men” (Grundy 7). “[S]tronger powers of men”? Certainly a position worth contesting! And Isobel reminded us of all the things that women in Persuasion do better than men: Mrs. Croft is not only a better driver than the Admiral but also “more conversant with business” (P 22). It is a male, Captain Benwick, who pines away for love, a woman who provides bracing moral advice (Grundy 10).

Elaine Showalter focused on Persuasion’s theme of “retrenchment,” not just in the financial sense of curtailing expenditure but as “a metaphor for withdrawal and recovery, for the ways that various characters, and especially Anne Elliot, deal with loss and personal defeat” (182–83).

Bruce Stovel, Elaine Showalter, Juliet McMaster

Bruce Stovel, Elaine Showalter, Juliet McMaster

And then of course there were breakout sessions, all striking in their ways, but too many to particularize. One that gained classic status was Jan Fergus’s witty anatomy of the whine, in a paper with the fetching title “‘My sore-throats, you know, are always worse than anybody’s’: Mary Musgrove’s Art of Whining.” Only at last year’s meetings, in Huntington Beach, Elaine Bander told us of Lake Louise, which was her very first AGM: “I kept hearing howls of laughter from [Jan Fergus’s] talk though the partition as I gave my own” (Bander 150). And there were other speakers, many of whom are still familiar: Edward Copeland, Gary Kelly, Joan Ray, Peter Sabor, Inger Thomson (now Brodey): stalwarts all, whom we have come to admire.

I too had my hour of glory. Thanks to Jack and JASNA, my own darling child The Beautifull Cassandra finally emerged in all her colored glory. Sono Nis Press obligingly couriered a box of copies, hot off the press, to the Chateau, and she sold like hotcakes. My Beautifull Cassandra has actually produced progeny a-plenty of her own. To go with the story and pictures, Joanne Forman composed music for flute and Celtic harp, which was performed live at the Chicago AGM of 2008 and in turn inspired a children’s ballet, where the dancers came dressed as my Viscount, pastry-cook, and so on (“The Beautifull Cassandra”). Moreover, working closely on Austen’s youthful text taught me how much can be learned from an author’s early work, and so I took the idea to the classroom and founded the Juvenilia Press in order to involve students in hands-on experience in textual editing, annotation, and so on. We now have sixty-something titles to our list, including, of course, many by young Jane Austen. Illustrating those has been another enjoyment. The Press has introduced dozens of students, all over the world, to the refinements of scholarly editing.

All that is a quarter of a century ago, and the 2018 AGM in Kansas City is actually the second one on Persuasion since ours at Lake Louise. Sad things have happened in the interim, as well as happy ones. Joan Austen-Leigh, the last of our three founders, followed Henry Burke and Jack Grey. Paula Schwartz is gone. Bruce died suddenly in 2007, soon after retirement. I lost my Rowland. Even while I was writing this paper, I paid my last visit to June Menzies, author of His Cunning or Hers.

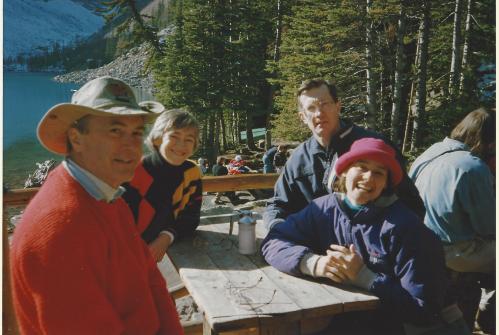

But I treasure certain pictures, certain memories. Gary Kelly came in full Admiral’s fig, sword and all, and looked stunning. At the banquet an attractive delegate asked him pointedly, “Are you attached?” His wife, Jennifer, sitting beside him, said “YES, he is!” I saw Margaret Drabble at a window writing a postcard. The scene in the postcard was almost exactly the scene she could see out of her window. It was a treat to catch a writer writing, in that beautiful place, about that beautiful place. Only just before I delivered this paper in Kansas City, Erika Kotite, JASNA’s new Vice President for Publications, showed me a photograph from that memorable Lake Louise occasion: of her husband proposing to her—dressed as Mr. Darcy, no less! (Yes, she accepted him!)

Tim Hayes and Erika Kotite

Tim Hayes and Erika Kotite

After the conference, Bruce and I co-edited a collection that we called Jane Austen’s Business, which included several of the papers also published in Persuasions 15. Ed Copeland, who had spoken on his favorite subject of money in Jane Austen, invited me to be his co-editor on The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen, and we’ve now published two editions and become close friends in the process. So memories of Lake Louise still vibrate with me.

On the Sunday after the AGM, when some people were taking a snow-cat ride up Columbia glacier and others going home, Rowland and Bruce and I took a hike up to Lake Agnes. The birds there will eat out of your hand. Another hiker joined us—the girl in the pink hat. As the last scene of all in this eventful history, the image I leave you with shows Rowland and Bruce and me, resting on our laurels in that beautiful place.

Rowland McMaster, Juliet McMaster, Bruce Stovel

Rowland McMaster, Juliet McMaster, Bruce Stovel

NOTES

1In the event, and late in the day, Lionel Trilling had to cancel, since he had just received the diagnosis of the cancer that was soon to kill him. The paper he would have presented—“Why Read Jane Austen?”—was subsequently published in TLS. Ian Jack kindly came at short notice to fill his place in the program. Other speakers were Lloyd W. Brown and George Whalley. I published the conference proceedings as Jane Austen’s Achievement

2See Joan Austen-Leigh’s presentation at the memorial for Jack Grey at the Lake Louise AGM. She explained that on July 19 of that bicentenary year she had been asked to thank the speaker at the gathering of the British Jane Austen Society—“in the famous tent in the grounds of Chawton House—which has now been saved for posterity by Sandy Lerner” (“For Those” 2). Jack introduced himself and—urged on by Joan’s husband Denis Mason Hurley—they began to talk of founding a Jane Austen Society of North America.

3Devoney Looser records that Sir Hugh “joked that he never read Austen’s novels” (132). According to my local friend, that was no joke, but the literal truth—and something he was rather proud of.

4My talk at Chawton was on “The Symptoms of Love,” which formed the first chapter of my book Jane Austen on Love.

5Nora Foster Stovel, originally a scholar of the modern novel, has given a number of breakouts at JASNA; after Bruce’s death she edited a collection in his memory, Jane Austen Sings the Blues, and subsequently collected his essays as Jane Austen and Company. Rowland McMaster, a Dickens and Thackeray man, addressed Jane Austen societies in Sydney, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver, on Waterloo, Trafalgar, and women at sea.

6The debate over the virtues or otherwise of “academic” approaches to Austen has been a feature of JASNA’s discourse over the years. See Elaine Bander on “JASNA and the Academy” and Juliette Wells’s chapter on “Reading Like an Amateur.”

7That is, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. It was Bruce who prepared the winning grant application.

8At the Kansas City AGM, I donated the originals of my illustrations to the North American Friends of Chawton House Library in support of Chawton House.

9Times Literary Supplement (2 Dec. 1993).

10Neil Moyer composed the melodies, and for our production Richard Link created the arrangements for the four-piece musical group.

11John Henry Lefroy, as Bruce Stovel explained in JASNA News of 1992, “was a military surveyor whose trip by canoe and dogsled though northwestern Canada in 1833–1844 yielded data of great scientific importance. [He] later rose to the rank of general in the army, served as governor of Bermuda and of Tasmania, and was later knighted.”

Falling in love

Falling in love Setting off

Setting off “ . . . the one book which he finds indispensable”

“ . . . the one book which he finds indispensable”