This essay announces the discovery of the exact location of Jane Austen’s box at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London, on Saturday, March 5, 1814, the night of Edmund Kean’s performance as Shylock in William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. The essay sets out the number of people in the Austen party and names some of the box’s other occupants. It also details the box’s location in the auditorium and offers a discussion of material contextual issues, such as the Austen party’s presumed sight-lines of the stage and the theatre’s total receipts that night.

The essay entails diving into the sociability of early nineteenth-century British theatre, not least including the details of auditorium seating.1 On account of protective royal patents, Georgian London only had two theatres permitted to perform the spoken word, Covent Garden and Drury Lane. The latter had reopened in October 1812, rebuilt by Benjamin Dean Wyatt, after a disastrous fire in 1809, and run by a new management committee headed by Samuel Whitbread of the brewing dynasty. By the time Kean came along, the Drury Lane company was flagging and its receipts falling. His overnight fame as Shylock on January 26, 1814, brought the theatre measurably increased audiences and income.

The scale of London theatre may be surprising. Even before its rebuild, Drury Lane held 3,611 people (and Covent Garden almost as many) (“Andrew Cherry” 169). Audiences would expect to see a “mainpiece,” normally a comedy of manners or a tragedy, followed by an “afterpiece,” usually a farce or a pantomime. References to crowded, hot, and fractious theatres are commonplace and not confined to the royal theatres. On their night, the Austen family was probably fortunate in being able to stay at Henry Austen’s house in nearby Henrietta Street, since the weather that day was, as it had been all week, a mid-winter mix of snow and rain (Cary).

The literary source for our knowledge of the Austens’ visit is mainly contained in Jane Austen’s letter to Cassandra dated 2–3 March 1814: “Places are secured at Drury Lane for Saturday, but so great is the rage for seeing Keen that only a 3d & 4th row could be got. As it is in a front box however, I hope we shall do pretty well.—Shylock.—A good play for Fanny. She cannot be much affected I think. . . . The two vacant places of our two rows, are likely to be filled by Mr Tilson & his Brother Genl Chownes.”

The principal findings can be easily stated.

The Austens were registered in Drury Lane’s Box Book under what was most likely the name of her brother Henry Thomas Austen (“Mr. Austin”). As her letter states, they were in the “3d & 4th row” of what is now identifiable as Stage Box number 13, on the “Prince’s Side” of the auditorium, seated behind the twelve-strong party of “Lady C. Copley.” Behind the Austens was a “Mr. Hoare,” apparently theatre-going on his own. “Lady C. Copley” is identifiable as Lady Cecil Copley (1770–1819), the divorced 1st Marchioness of Abercorn but by that time the wife of a baronet.2 Lady Copley is the only member of her party who can be firmly identified because she gave her name to the Box Keeper (if not in person then through a servant or someone else acting as her agent). The context of the Copley and Hoare parties will be the subject of a separate essay, which will include more extensive information about their identities as well as those of some other occupants of this tier of boxes.

Folger Z.e. 16. Courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C.

Folger Z.e. 16. Courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C.

In the Box Book entry, Henry Austen’s name (“Mr. Austin”) was positioned between that of Lady Copley and Mr. Hoare, consistent with Austen’s understanding that they were in the “3d & 4th row.” From the layout of Drury Lane’s pre-printed Box Book, Box 13 in that tier was the one nearest the stage (the box had its symmetrical equivalent on the “King’s Side,” laterally opposite). Austen refers to it in her letter as “a front box.” Situated above the Orchestra Boxes, which were level with the sunken orchestra pit, the Austen party in Stage Box 13 would have been looking slightly down on Kean and from an extreme lateral angle of about 10–20 degrees (giving them a good view but a very oblique view). Of course, unless they stood up or craned their necks, their sightlines would have been obscured by the Copley party in the first and second rows. Mr. Hoare, behind them, would have had an even worse view.

This information is contained in the Drury Lane Box Book of box occupancy now in the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C. (Folger Z.e.16). The book comprises a substantial, pre-printed auditorium occupancy layout, tier-by-tier and box-by-box, of the theatre’s boxes set out as a calendar sequence of performances. Locating the entry is simply a matter of calling up Folger Z.e.16 and then referring to the date March 5, 1814.

In the Box Book, each night of box attendance can be examined with the book opened out flat, a single night occupying both the left (verso) and the right side (recto) pages.3 Empty space across the top of the two pages allowed the Box Keeper to write in the performance date and the titles of the mainpieces and afterpieces. Although it had a number of uses, the Box Book was probably principally prepared for the theatre’s financial record-keeping and was probably ultimately intended for Drury Lane’s treasury department (back-office accounts in today’s parlance). It may also have been used, since aristocratic titles are often included, as a management “who’s-who” guide to the identities of rich and influential patrons. The Box Book was not particularly intended as a physical map of the auditorium or as a seating-plan in the modern sense.

Each printed box was assigned a printed sequential number. The printed box (with its number) is an empty rectangle for the Box Keeper to record in it the name of the person or persons who had responsibility for taking the box. Sometimes an address was also provided. For example, the radical author and activist “Mr [John] Thelwall” (1764–1834) is instantly recognizable because on February 21, 1814, he took a box (apparently alone) for Richard III, giving his address as “Lincolns Inn Fields,” his residence only since 1813.

More often, however, as with “Mr. Austin,” the entry just records the individual’s title and the family name. Those boxes printed nearest the bottom of the page refer to the auditorium boxes nearest the stage (with the Prince’s Side and King’s Side adjoining each other, separated longitudinally). The boxes at the top of the page indicate those boxes farthest away from the stage. The boxes farthest away (at the bottom of the horizontal “U” of the tier) had the least interrupted or awkwardly angled view of the stage. They also had optimum visibility for being seen by other theatre-goers. The Austen box did not have any of these advantages. As a rule of thumb, on the nights of Kean’s performances at Drury Lane in the 1813–1814 season, his first, the boxes at the top of the page tended to fill up with titled aristocracy. Lower down the Box Book page, where the Austens’ box was printed, there was a lesser array of hereditary titles, although, as on this particular night, so great was the rush for Kean that the best seats in the Austen box were those of the party of “Lady C. Copley,” the box’s stray aristocrat.

The Drury Lane pre-printed Box Book was manufactured specifically for that theatre, uniquely matching its auditorium layout. Improved financial record-keeping seems to have been part of the new management methods initiated by Whitbread.

The names in the Box Book are nearly always entered in the same hand. For Box 13, the occupants are identified as “Lady C. Copley,” “Mr. Austin,” and “Mr. Hoare.” It is likely that the theatre’s procedure was simply for principal persons in each party to announce their arrival to the Box Keeper, with the Box Keeper then writing their name down for them (rather than asking them to sign in themselves). Overall, women (as designated by the title of “Mrs.” or “Lady,” for example) announced themselves as principal box occupants at least as frequently as male box takers. For the Austen party, however, the name supplied to the Box Keeper is unquestionably prefixed “Mr.”

As was the case at other theatres, the Box Keeper was a specific post at Drury Lane. At least as early as 1735, the Haymarket theatre staged performances of La Fille Capitaine, & Arlequin Sergeant, ou la Fille Savante: or, The Woman Captain and Harlequin Serjeant, or The Philosophical Lady for the benefit of their Box Keeper.4 The resulting regularity of this single responsibility means that entries in the Box Book are generally entered to a consistent quality and style. However, not all the details of the Drury Lane Box Keeper’s working methods are now clear. Of course, as long as the Box Keeper maintained a method explicable to colleagues, the theatre could evolve its own culture of recording information. While this method was certainly sufficient for Drury Lane’s management purposes, some details today may not be fully comprehensible.

As far as the Austens’ night is concerned, an obstacle to absolute clarity is figuring out the total number of people occupying Box 13. This is important because it could be a good indicator of the degree of concentration audience members were able to give to their viewing and listening experience.

In many (but not in all) cases, the responsible occupant’s name was accompanied by a number, sometimes alongside the letter “p.” It is not possible to be absolutely certain as to the meaning of these numbers or lettering, but they are, on balance, most likely to refer to the total number of people in that particular party.

On the Austens’ night, the full entry reads, “Lady C. Copley 6/6,” “Mr. Austin 6p,” and “Mr. Hoare 1p.” This suggests that the letter “p” means “places,” the terminology also used in Austen’s letters. If the numbers after the names refer to the number of people in each party, since it is known from her letter that the Austens were in the “3d & 4th row,” this suggests they were seated as a party of 3 + 3. For the Copleys, the entry of “6/6” suggests they were seated as a 6 + 6, that is, six in the first row and six in the second. Including “Mr. Hoare 1p” would make a total of nineteen people occupying Box 13. Whatever the exact physical seating layout of the boxes, a 6 | 6 | 3 |3|1 configuration would at least have the advantage that those towards the back of the box would be able to move around to see over or around those seated in front.

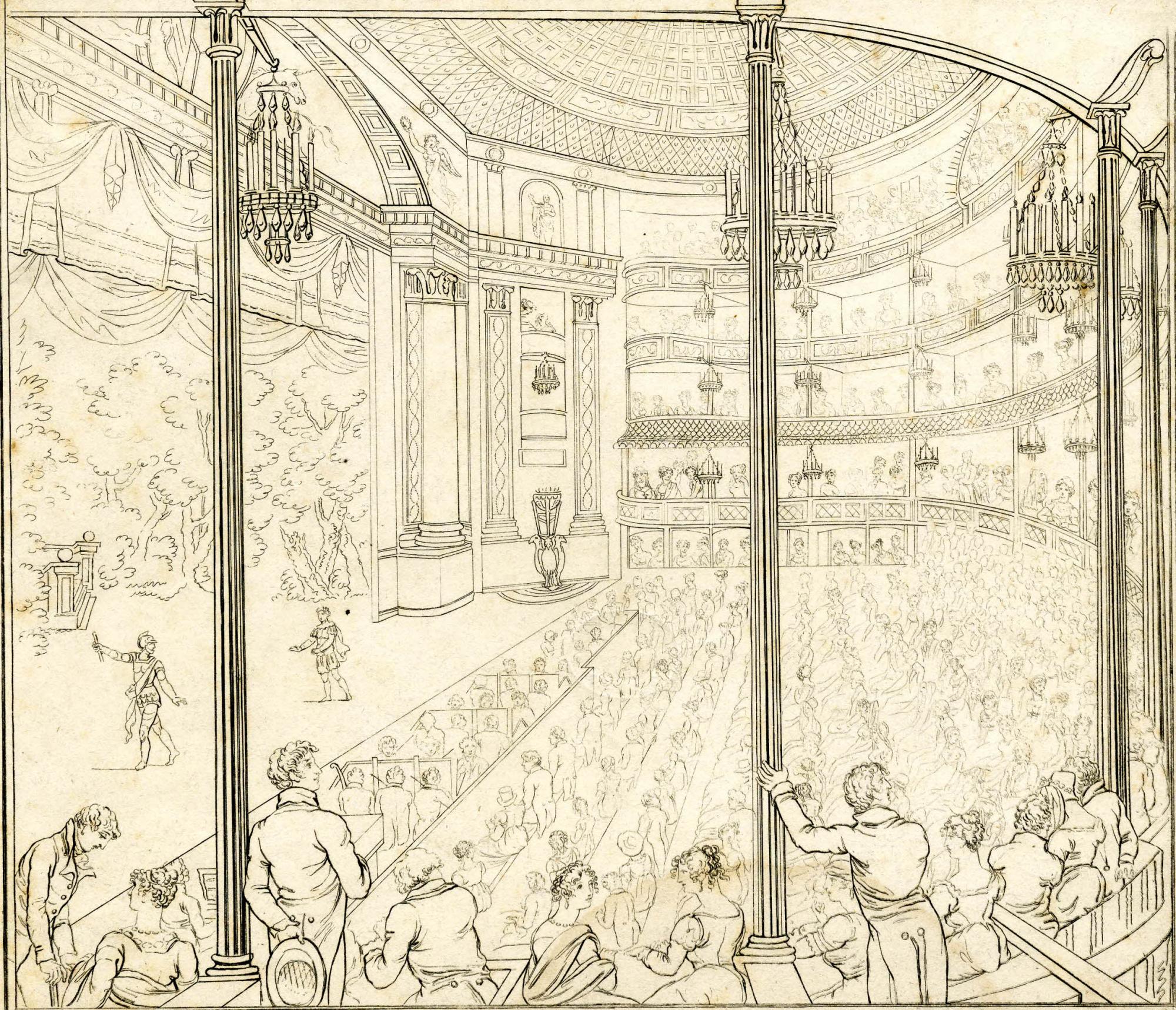

A suggestive visual source for Drury Lane’s new auditorium, very conveniently portraying a perspective across the space from the back of one of these very same front Stage Boxes, can be found in the 1813 etching entitled Interior View of Drury Lane Theatre. This print, however, although wonderfully atmospheric and certainly published after Drury Lane’s reopening in October 1812, must be treated with caution as it seems not to faithfully record the interior plans proposed by Wyatt in his Observations On the Design for the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, As Executed In the Year 1812 (1813), plate 9.5

Interior View of the Drury Lane Theatre

Interior View of the Drury Lane Theatre

Courtesy British Library

The presence of a supporting pillar illustrated in the print means that the boundaries between boxes are not particularly easy to determine, although Heideloff seems to show two groups of six people (or, a two, a four, and a six), all fashionably dressed. Of these, seven are women and five are men. Three of the men are standing, none of whom is looking at the stage. Only four of the spectators (three women, one man) seem to be looking directly at the stage (on which is being performed a play in classical costume).

The six members of the Austen party, judging from inferences able to be drawn from Jane Austen’s letters between March 2 and 8, 1814, was an excursion comprising Jane Austen, Henry Thomas Austen (1771–1850), their niece Fanny Knight (1793–1882), James Tilson (1773–1838), Lieutenant General John Mackenzie Christopher Chowne (1771–1834, who had changed his name from Tilson on 14 January 1812) together with—very probably—Jane’s brother Edward Knight (1768–1852), who, with his daughter Fanny, had arrived on March 5.

It is unlikely that all of them would have been able to see the stage with an uninterrupted sightline for the entirety of The Merchant of Venice and the afterpiece, Frances Chamberlaine Sheridan’s, The Illusion; or, The Trances of Nourjahad: An Oriental Romance, with music by Michael Kelly (1813). Writing to Cassandra on the morning after the excursion to Drury Lane, Austen says, “We were quite satisfied with Kean. I cannot imagine better acting, but the part was too short” (5–8 March 1814). She makes no mention of there being restricted viewing caused by eighteen other people in the box but then, on the other hand, neither does she mention the extreme viewing angle the Austens’ box undoubtedly imposed or even, for that matter, any consequences specific to the fact that “only a 3d & 4th row could be got.” In that same letter, however, Austen writes, “We were too much tired to stay for the whole of Illusion (Nourjahad) which has 3 acts.” Sightlines impeded by Lady Copley’s party may have contributed to this tiredness.

When these “6/6,” “6p” and “1p” numbers and letters were inserted into the record for Box 13 by the Box Keeper is difficult to determine. It is entirely possible the names of the principal occupants were entered some days before the performance if the box had been reserved in advance. The Austens obviously had a reservation, which may even have been made some weeks earlier. It is also possible, however, that box occupancy numbers were only noted at the last minute, on the night of the show. A totaling up of party numbers, as they announced their arrival, would have had the advantage from the Box Keeper’s point of view of providing some idea of spare seating capacity at his disposal. The Box Book was the theatre’s sole record of occupancy distribution per box. Noting the numbers of each party on arrival would allow the Box Keeper discretion as to where to squeeze in any late, unannounced arrivals, presumably including those who had turned up speculatively requesting a box. Whether half price arrivals (another distinctive audience category) are included in any of these names and numbers cannot be ascertained (although it seems unlikely they were recorded).

That night, for example, and despite Jane Austen’s declaration of the difficulty in obtaining seats, only 11 of the 18 Orchestra Boxes are shown in the Box Book as occupied. Of course, it is perfectly possible these were filled on the night but not recorded due to haste or administrative error. Discrepancies between the Box Keeper’s records and the actual night’s receipts were not too disconcerting from a financial management point of view because there also existed a separate account book that recorded the evening’s receipts totaled up from all parts of the auditorium. Again, this book was pre-printed (this time in red ink), almost certainly another of Whitbread’s innovations. This book showed the nightly distribution of receipt sub-totals in different seating areas right across the auditorium, segmented both horizontally and vertically.

Seat prices at Drury Lane were usually 6 shillings in the boxes, 3s.6d. in the pit, 2s in the gallery, and 1s in the upper gallery, usually with half price at half time. With all the prices, there were ad hoc variations. For some reason, Orchestra and Proscenium Boxes are recorded more regularly than others, priced at either £2.12.6. or £3.3.0. (although it is not clear whether this reflects a price for the box or the numbers of people in it). When Lord Byron went there on February 26, also to see Kean’s Shylock, he paid £2.12.6. for a Proscenium Box. It is far from clear whether he was alone.

For the night of March 5, the total theatre receipts were £194.5.0. for the boxes and £113.15.0 for the pit. Along with what Drury Lane itemized as the “Second Account” (“half price” money from the previous evening’s performance, which was not usually recorded until the next night), the grand box office total for the Austens’ night was £408.16.0. Despite the Austens’ evident difficulty in obtaining seats, Kean’s Shylock on 5 March compared somewhat less financially favorably with receipts for his Richard III on the previous night of his performances (Thursday, March 3). On that night, total receipts (including the slightly misleading “second account” delayed money), came to £655.13.6., with £376.11.0. derived from the boxes (not including the previous performance’s “second account” money).6 Again, despite the Austens’ difficulty in finding seats, there were fewer people there to see The Merchant of Venice on the Saturday than there had been for Richard III on the Thursday.

Even by this point in the narrative of the Austens’ night at Drury Lane, some degree of circumspection is required in considering the status of the event. Kean’s debut as Shylock had been on January 26, 1814. His rise to fame was rapid, but his reputation in The Merchant of Venice was already being overtaken (as the box office receipts referred to above demonstrate) by that of his title role in Richard III which had opened on February 12.7 Theatre finances, however, are consistently unpredictable. At the end of the season, Edward Warren, an Assistant Treasurer (accountant) at Drury Lane, was asked to calculate the average box office receipts for Kean’s performances. The average for The Merchant of Venice was £351.10.0. while the average for Richard III (their top earner) was £562.10.8.8 Although receipts on the Austens’ night were slightly below par, the Richard III performance, which they missed on Thursday, March 3, proved to be—despite the bad weather that week—the theatre’s second highest overall receipt that season for any performance (again, Warren had been asked to work out the figures).9

Nevertheless, even taking into account the weather as a variable in drawing audiences, it is problematic to compare the relative popularity of titles. “Runs” of plays in the modern sense did not happen at that time. Although not exactly alternating the two works, while Drury Lane continued to program The Merchant of Venice in tandem with Richard III, the afterpieces were changed almost nightly as the company worked through its secondary repertoire to maintain variety. Whereas Austen left The Illusion early, on the night of Richard III, two days earlier, the audience had been offered a ballet and Samuel Foote’s enduring farce The Mayor of Garratt (1763). Kean also needed to rest, recuperate, and contemplate his next big role. That season, in Othello, Kean played both Othello and Iago (not, of course, on the same night). By March 5, Jane Austen was witnessing Kean in his first, but not his latest, Drury Lane role.

Curiously, a “Mr. Austin” is recorded seated in Box 20 (King’s Side) on February 19, on the second night of Richard III, accompanied by the designation “6p.” This “Mr. Austin”could be Henry Thomas Austen (or just Any-Other male Austin or Austen). The box next to “Mr. Austin 6p” was occupied by “Mr. G. Hammersley,” just possibly George Hammersley, by then a partner in the bank of Hammersley & Co. and possibly professionally known to Henry Austen through Henry’s role as a partner in the Austen, Maunde & Tilson bank. If Henry—if it was he—had five guests, the event would have been a kind of bankers’ outing. Although this is all highly speculative, a February 19 visit by busy banker Henry would have had at least have facilitated an opportunity for making a reservation for The Merchant of Venice on March 5. Austen’s statement in the letter that “Places are secured” may refer to Henry’s acting in this capacity. Even then, however, it is not at all certain that Drury Lane would have known on the February 19 that The Merchant of Venice would be performed on the March 5. Jane Austen may have known from shortly after February 19 that she was going to Drury Lane to see Kean on March 5, but she may not have been able to choose whether it was The Merchant of Venice or Richard III.

With all of these theatrical details, as with the finances, one needs to allow for some level of confusion and imprecision. Theatre employees were not always effective and efficient in managing the nightly inflow and outflow of three thousand paying guests.

If nineteen people to a box sounds cramped and uncomfortable, one needs to put it into perspective. Wondering what he was worth financially, at the end of Kean’s first season Warren of Drury Lane’s treasury department totaled up the number of seat sales that year (including complimentary seats issued) and found that the number came to 484,691, precisely.10 It is now possible to say with confidence that where Jane Austen sat, in the third or fourth row of Stage Box 13, meant that her bench seat, squashed behind the Copley party, was just one addition to another 484,690 places taken that season at Drury Lane. Luckily, she was “quite satisfied with Kean.”

NOTES

1For introductions, see Byrne, Gay, and Worrall’s “Social Functions: Audiences and Authority.” I am grateful for a Folger Shakespeare Library Short Term Fellowship in 2017, which enabled me to make the discovery upon which this essay is based.

2Distinguishing English aristocracy from English gentry has long been a subject of debate. My simple solution has been to assume that any honorary or hereditary title denotes an aristocrat. The complications are evidenced in the case of Lady Copley. She had once been a Marchioness, one of the highest hereditary titles, although she had only been able to marry into that aristocratic level because she had previously been raised into equality with that rank—some years before her marriage—through the granting of a rare personal designation of “Precedence” by George III. By 1814, long after her divorce from the Marquis of Abercorn, she had become the wife of a baronet, the lowest hereditary title. Distinguishing the correct nomenclature and equivalence for historical theatre-goers, within an honors system founded on birth parentage and gendered rights of succession, is almost impossible. The situation for Irish peers, some of whom appear in boxes attending Kean’s performances, makes direct equivalence even more fraught. For a summary of the origins of the debate among historians, see Coleman, along with Tobin and Downie, for discussions of its relevance to Austen.

3Of course, the Box Book should absolutely not be opened out flat but cradled in the foam supports that the Folger Library supplies plentifully in the reading rooms.

425 April 1735, Daily Advertiser.

5My thanks to Iain Mackintosh for pointing out the discrepancy at “The London Stage and the Nineteenth-Century World, II” conference, New College, Oxford, April 2018.

6Folger W.b. 327, Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C., hereafter Folger.

7For a discussion of Kean’s audiences and rising celebrity, see Worrall’s Celebrity, Performance, Reception.