The Victorian poet Edward Fitzgerald once commented that Jane Austen “is capital as far as she goes: but she never goes out of the Parlour” (qtd. in Gilbert and Gubar 109). Writing on a completely different topic, sociologist Erving Goffman uses similar terms. Explaining how games generate excitement, he writes,

Looking for where the action is, one arrives at a romantic division of the world. On one side are the safe and silent places—the home, the regulated role of business, industry, and the professions; on the other are all those activities that generate expression, requiring the individual to lay himself on the line and put himself in jeopardy. (Di Filippo 241)

The idea that Austen’s fiction is circumscribed, unexciting, “safe,” whereas games are not, is probably why news of an Austen-themed video game struck gamers and journalists alike as odd. What could there possibly be to do in a Jane Austen game? Granted, some of her characters do play games, such as cards, in the novels, but she has hardly enjoyed a reputation for an action-packed oeuvre. Nonetheless, Ever, Jane, an immersive MMORPG (massively multi-player online role-playing game) developed by video-game industry veteran and Austen fan Judy Tyrer, launched in August 2016.

Ever, Jane has actually been rather widely reviewed in the game industry—and well-reviewed, at that. Further, reviewers have registered an honest astonishment when their expectations of being bored in Ever, Jane have proven to be wrong. In turn, some Janeites may be surprised by the activities of many of the game’s regular players. The game is actively disruptive, on more than one level. It unsettles some popular preconceptions about the novels as primarily reading material for ’tween girls or maiden aunts, but, equally, it unsettles the divisions on which the meanings of “action,” “game,” and “story” depend. What happens when Austen meets MMPORG? Something thoroughly subversive, I argue, and not in spite of the unlikely combination but, rather, because of it.

My argument is necessarily broad, spanning the complex network of relationships constituted by reviewers, developers, players, and text in order to trace its most interesting and salient common feature. I want to address first how industry reviewers have understood what there is to do in Ever, Jane and to contextualize their comments against what is meant by the word “action.” Next, I approach the question of how the game’s developers have understood Austen’s fiction as playable and how they position the game vis-à-vis other MMPORG offerings. What players actually do in the world of Ever, Jane is yet another variable, and I shall turn to this topic last, along with the problem of how to distinguish a story from a game.

![]() Reviewing Ever, Jane for industry media giant IGN Entertainment, two anonymous, male reviewers echo Fitzgerald’s sentiment about Jane Austen. They are not expecting much to happen in this game. They begin their vlog review by noting that Austen’s novels are “all from the female perspective,” so they choose a female avatar. After debating whether to call the avatar “Elizabeth Bennet” or “Elizabeth Báthory” (the Hungarian, Renaissance-era serial killer of young women), they jokingly add, “We thought the Parlour button said ‘Parkour.’ Don’t click that. Don’t ever click that” (“We Crashed” 1:30, 4:44). Ten minutes later, however, they’re delightedly riding around town in a coach-and-six, dashing up and down stairs in search of a lost handkerchief, pushing over NPCs (non-player characters), and chasing an errant sheep through a pasture. They confess themselves unexpectedly charmed, admitting that the game has rather won them over. Notice that the distinction between “parlour” and “parkour” has been undeniably muddied.

Reviewing Ever, Jane for industry media giant IGN Entertainment, two anonymous, male reviewers echo Fitzgerald’s sentiment about Jane Austen. They are not expecting much to happen in this game. They begin their vlog review by noting that Austen’s novels are “all from the female perspective,” so they choose a female avatar. After debating whether to call the avatar “Elizabeth Bennet” or “Elizabeth Báthory” (the Hungarian, Renaissance-era serial killer of young women), they jokingly add, “We thought the Parlour button said ‘Parkour.’ Don’t click that. Don’t ever click that” (“We Crashed” 1:30, 4:44). Ten minutes later, however, they’re delightedly riding around town in a coach-and-six, dashing up and down stairs in search of a lost handkerchief, pushing over NPCs (non-player characters), and chasing an errant sheep through a pasture. They confess themselves unexpectedly charmed, admitting that the game has rather won them over. Notice that the distinction between “parlour” and “parkour” has been undeniably muddied.

Similarly, Jon, the reviewer for ManyATrueNerd (MATN), one of YouTube’s most popular game review channels, initially scoffs at the notion of an Austen-themed video game: how on earth do you play a game about courtship, and why would anyone want to? As do the IGN reviewers, he initially wanders around the simulated Regency village of Tyrehampton, looking for something to do. Having read that the game is an MMO, though, Jon is particularly looking for other players. When he finds one, he considers how best to be civil to this other player. Manners mattered in the Regency period, he insists, as he tries out the buttons that will allow his avatar to bow or to curtsy. After much bowing and a brief dialogue with the other player via the chat window, he concludes, “I actually really like this game. It’s clear it was made for love, not money” (“Ever, Jane—MMO Mr. Darcy” 31:18). Possibly a furtive reference to Austen (or possibly not), his confession makes one thing clear: he’s had a change of heart.

Where the IGN reviewers seem most to have enjoyed moving around the terrain, both in and out of doors, the MATN reviewer seems most to have enjoyed meeting the other player. Their enjoyments are aligned with two different though related definitions of action: the first, from game studies, and the second, from game theory. In game studies, the standard definition of “action game” cites an emphasis on sensori-motor skills and a repertoire of short-term sequences (Arsenault 233). Yet, as Dominic Arsenault observes in his chapter “Action” in the Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies, neither industry journalists nor researchers in game studies have been particularly interested in exploring this definition. He further reflects that the meaning of “action” as well as its connection to “action game” has been largely taken for granted, suggesting that Tzvetan Todorov’s paratextual argument has been taken as evidence enough for the existence of the “action game” as a genre: “it stands as a historical genre (whose existence can be pointed to in historical reality by referring to paratextual materials such as game reviews, marketing, etc.), without a corresponding widely agreed-upon theoretical genre (an analytical category that can be deduced or conceived, abstracted from any given incarnation)” (234). And Arsenault is right. Even without an agreed upon academic definition, there is certainly no practical misunderstanding among the gaming community at large about what an action game is. Action games have consistently declared a combat focus, with gameplay descriptors like FPS (first-person shooter) and titles like World of Warcraft, an MMO that has evolved into an international e-sport.

The multi-player aspect, I would suggest, is as important as the sensori-motor. Like the interdisciplinary study of play and sports, game theory relies on a fundamental and often unquestioned understanding of the word “action,” one in which multiple actors are required. Kevin Binmore offers a refreshingly succinct definition of action in game theory: where two or more agents are involved, their relationships are expressed as “action”; action is thus essentially indistinguishable from “interaction” (1). Clearly, game theory casts a wide net. With this definition, a host of cultural objects and practices, including any novel, can be parsed as action games.

Of course, most MMOs will combine both sensori-motor and interaction elements. Ever, Jane differs by demanding that what counts as action be noticed and does so precisely through its tongue-in-cheek overturning of expectations. Ever, Jane suggests the idea of Austen’s storyworlds as lacking in action to be a lie, makes the parlor the location of athletic feats, and makes us notice the physical work of social interaction (including our use of the buttons that allow the avatar to bow or to curtsy). Ever, Jane gleefully conflates its forms of action, respecting no disciplinary boundaries. Thus both the IGN reviewers and MATN’s Jon surprise themselves by finding something to do in Ever, Jane provoking the question: is Ever, Jane an “action game”?

At the other end of the spectrum from the action game is the life-simulation game, represented by offerings such as The Sims franchise. In these games, housing, clothing, social activities, and relationships are favored over combat and/or displays of simulated physical skill. These titles are not popularly described as action games and, historically, have been more heavily favored by female gamers. In games, as in literature, we might concisely denote this emphasis on domesticity and relationships—the safe spaces, according to Goffman—as “playing house.” Yet Ever, Jane sets about dismantling the distinction between action games and life-simulation games, too.

3Turn Productions (Click here to see a larger version.)

![]()

In an interview with Jessica Conditt for Engadget, Tyrer explains why she wanted to make Ever, Jane: “A lot of people don’t want to play ‘I’m killing things’ games. It’s very offensive to many, many people.” With experience in both combat-oriented action games and life-simulation games, as well as single and multiplayer platforms, Tyrer certainly understands the industry and the assumptions around gender and genre that operate within it. Tyrer was a network engineer for the Ghost Recon franchise, a tactical first-person shooter series published by Ubisoft, before moving to Linden Labs to work on the online life-simulation game, Second Life. She tells Elyssa Chenery of KillScreen that with Ever, Jane she wanted to create a game where the focus would be squarely on role-playing without the distraction of combat, and since she was already an Austen fan, she wanted to make a role-playing game based on Austen’s fiction. Tyrer then founded a small development company, 3Turn Productions, to work on the project. Raising over $100,000 US on Kickstarter within only a few months, Ever, Jane caused a bit of a stir with the unusual success of its campaign for an indie game of its size. As a result of the six-figure campaign, Tyrer was interviewed by major gaming magazines, and gaming news giants like IGN reviewed the playable Beta. Although Tyrer’s love of Jane Austen had brought the game to life, it was the money that brought it to the attention of industry journalists.1

Clever marketing helped as well. Ever, Jane marketing description is designed to appeal to a range of players along a spectrum of gameplay styles, in spite of its self-professed niche status. The marketing description appears to assert the game’s difference from combat-focused action games, but, in the same breath, it masterfully uses juxtaposition to unsettle the difference between them and itself (Ever, Jane, Home Page):

Unlike many multi-player games, it’s not about kill or be killed, but invite or be invited. Gossip is our weapon of choice. Instead of raids, we will have grand balls. Instead of dungeons, we will have dinner parties.

Austen’s concern with social hierarchy, vicious gossip, shattered reputations, and the desperation of the cash-strapped is not so unlike “many multi-player games” after all. Invitations to join leagues or guilds, like invitations to Regency dinner parties, are the status markers of MMOs and e-sports and greatly coveted, especially by neophytes. Similarly, insults hurled during gameplay in MMOs (“trash talk”) can sometimes have consequences, such as loss of invitations to events, loss of in-game currencies, or being banned from the game altogether—consequences not so unlike the disastrous results of gossip, slander, and lies in Austen’s novels. As for raids and dungeons, these usually provide MMO players with opportunities to gain resources and achievements. Ever, Jane reinscribes these features in alignment with Austen’s sagacity about the necessity of balls and dinner parties to improve young ladies’ and gentlemen’s fortunes. Neither did industry journalists miss Tyrer’s parody of Daybreak’s historic MMORPG title, EverQuest.

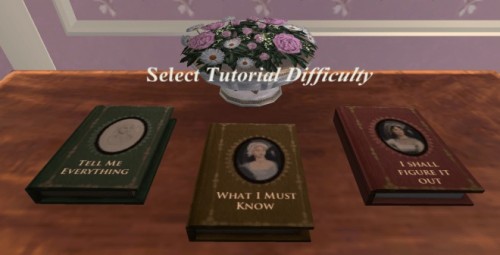

Ever Jane’s advertising description is fascinating in part because its job is to establish expectations about the game, and it performs this job while also using popular preconceptions about Austen to its advantage. The fact that it is also a fairly accurate summary of how the game’s events and activities strikingly mirror more mainstream MMOs is pure genius. Joining the game for the first time, players initially encounter the tutorial quests; even casual gamers will know why and what a tutorial is for. It’s expected. Ever, Jane’s tutorial is accessed via a writing desk in any of the village houses, where players may select from a handful of gilt-stamped books, each bearing a title corresponding to one of the quests. Players can return a lost handkerchief to the NPC named Dorothea Hatch; help another NPC, Shepherd Brimley, harness a stray sheep; or search for flowers in and around the village to make a bouquet. In other games, tutorial quests are meant to help players collect resources that will be useful later in the game and are often accompanied by specific and progressive achievement awards; they also may increase the level of danger as the tutorial progresses. Yet in Ever, Jane all of the tutorial tasks are distressingly mundane; none of them is hazardous or provides any resources that will help the player later on. Although the tasks do fulfill the sensori-motor requirement for action, and, like the IGN reviewers, players can choose to exaggerate the simulated stunts by performing them recklessly, at the same time Ever, Jane’s tasks humorously defeat expectations fostered by conventional MMO titles.

Only one of the tutorial quests results in a resource reward, and it, too, provides a wonderfully ironic reflection on gender and genre associations in mainstream MMPORGs. The quest “In Want of a House” entitles Ever, Jane players to buy a home and then to furnish it in Regency style using virtual money (purchased with real money from the Ever, Jane store). This quest more quietly provokes comparisons but is no less disruptive. It is a truth universally acknowledged that players in possession of game currencies must be in want of a house in which to store and display their loot. In commercial offerings like EverQuest, World of Warcraft (WoW), and The Elder Scrolls Online (ESO), “playing house” is not just for girls. In fact, MMOPRGs are notorious for monetizing player housing and furnishing options, all of which provide visual markers of player progression and advertise achievements while generating real-world income for the developers. Moreover, YouTube content dedicated to homes and furnishings in games is overwhelmingly male authored, as with the popular YouTube series ESO Cribs, or the plethora of video requests for the addition of player housing to WoW. Player expectations are also more directly mocked by the housing quest in Ever, Jane through its lack of requirements. Ever, Jane’s housing quest requires players to defeat no enemy, complete no difficult objective, or do much of anything at all in order to obtain so grand a reward as a house of one’s own. Imagine! Other games require hours of in-game toil to achieve a house, but Ever, Jane offers its lovely Georgian domiciles for, apparently, nothing. Again interrogating the meaning of “action,” Ever, Jane asks nothing of the player in exchange for a house but to select the right book.

3Turn Productions (Click here to see a larger version.)

Disappointment, however, can still occur. MATN’s Jon voices his sincere disappointment when he tries to buy a house in Ever, Jane only to meet with a message apologizing for a current housing shortage (26:54–29:58). A seasoned reviewer and gamer, Jon reveals his investment in the reward system of player housing through his reaction: “the property market here is absolutely ludicrous on toast.” More interestingly, his experience also comically mimics that of several of Austen’s own heroines. The housing shortage is not part of the game’s design and appears sporadically, but, when it does happen, it is deliciously in keeping with the experience of the Bennet girls, of Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, or even of Fanny’s precarious household status. Since the Napoleonic wars have resulted in a shortage of men in Austen’s fictional England, husbands are in meagre supply. Girls like Northanger Abbey’s Isabella must plot and play their way to husbands and thus to houses, notwithstanding Henry Tilney’s comment that women are expected to play the demure and passive role, while men have the privilege of active selection (74). To be sure, even developers must rely on practical solutions during times of shortage. 3Turn Productions addresses the housing problem by evicting players who fail to log in for more than thirty days. Ergo, inaction results in homelessness—in Ever, Jane as in Austen.

The remaining volume in the writing desk, “A Dismal Beginning,” introduces Ever, Jane’s multi-player mechanics by requiring a new player to join other players at a funeral for Darcy’s sister, Georgiana. When I played through this quest, I was initially shocked; Georgiana was always one of my favorite characters, and the developers had unceremoniously “killed her.” I did not discover how Georgiana had died, but I was happy to speculate.2 In other words, I had to make it up, and indeed, Georgiana’s death was the main topic of discussion among all the players at the funeral. Ever, Jane consistently conflates social interaction with making things up, creating an equation between lies, gossip, speculation, and storytelling. Even more disruptively, 3Turn Productions calls these storytelling activities “questing.” The “Official Ever, Jane Wiki” reads:

The quest system allows us to create story lines involving the various players in the game based on their goals, situations, and the story arc of the village. . . . In addition, our forums provide a place for players to publish their stories as they live them in the world. (Quests)

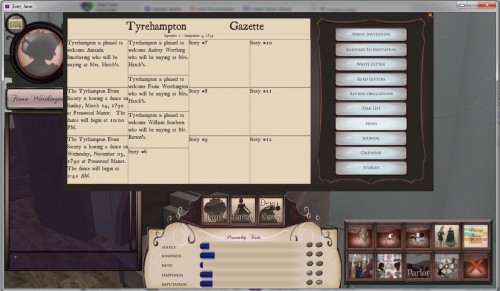

Players involved in the co-creation of stories are thus “questing,” while the UI (user interface) encourages the use of lies and gossip in the storytelling-quests by providing buttons for them. By making “LIE” and “GOSSIP” buttons to automate these actions, rather than leaving them for players to initiate themselves via the chat window, Ever, Jane pointedly also equates game functions with the social interactions of the storytelling-quests.

As detailed, then, Ever, Jane’s support for social interaction is two-fold, with both a chat window for typing in messages and a UI that allows repeated, short-term sequences at the click of a button, including “STEAL” and “FLIRT,” in addition to the “BOW,” “CURTSY,” “LIE,” and “GOSSIP” actions. As the Wiki description suggests, players may also virtually publish the stories they tell in-game on Ever, Jane’s community forum, perusal of which is advantageous to the player’s success in the game since reading the posts will help a player to understand better the plots and characters with which they will soon be embroiled. Again, Ever, Jane brilliantly invokes mainstream MMOs while paying homage to its namesake, spinning the typical MMO “trash talk” into Austen gold: the spreading of insults, gossip, and lies. Other community events include weekly player/character meetings and seasonal celebrations.

3Turn Productions (Click here to see a larger version.)

As of early 2019, 3Turn Productions was rumored to be working on a series of card games to be structured as multi-player mini-games. They promise to provide additional opportunities for both slander and its detection as well as to open specialized quest lines (Mini-Games). The proposed mini-games of cards will be particularly apropos, I think, reminding us of just how important games already are in the novels. For whether enjoying country dances, amateur dramatics, gig racing, parlor games, or cards, Austen’s characters are primarily at play. Austen’s detailed integration of games facilitates the social maneuvering for which these games serve as a backdrop. Card games are especially numerous, and Marianne Vignaux, in a talk delivered at a meeting of the Jane Austen Society of New Zealand, lists several, observing that they offer the means of “isolating characters so that [they] have the privacy to conduct business necessary to the plot.” Vignaux points out, for example, that Isabella’s choice of the game Commerce in Northanger Abbey reflects her actions in the choosing of a husband, as she exchanges one card for a better one in the hopes of improving her hand. I would add that even relatively minor characters are used as facilitators in this regard, as in Sense and Sensibility, where Mrs. Jennings tells Colonel Brandon that she needs him for Piquet and so provides Marianne with an opportunity of improving her hand as well. Though operating on different plot levels, the playing of leisure games and the telling of gossip and lies are nonetheless analogous activities in the novels. With its conflation of stories and quests and its automation of storytelling actions via button prompts, Ever, Jane would seem to take its cue in disturbing the distinction between a “story” and a “game” straight from Austen.

![]()

In reality, the distinction between a “story” and a “game” has been even more fraught in academic debate than the definition of “action.” Among specialists in narratology and in game studies, furious conversations have marked the division of stories from games. Twentieth-century definitions drew heavily on the landmark works of Roger Caillois and Johann Huizinga, and each has been widely referenced in both game studies and game theory. Both men, though, were interested in more broadly defining “play,” with games forming subsets of play activities. As video game technologies have advanced and developers continue to integrate more complex narratives, academics have grappled with increasingly slippery distinctions, leading ludologists sometimes fractiously to assert solutions based on the intuitive and the practical. Markuu Eskilinen, for instance, echoes Arsenault’s invocation of the paratextual for “action game,” tartly commenting, “Luckily, outside theory, people are usually excellent at distinguishing between narrative situations and gaming situations: if I throw a ball at you, I don’t expect you to drop it and wait until it starts telling stories” (36). Still, even Gonzalo Frasca’s initially promising and frequently cited 2003 distinction between the “external observers of stories” and the “involved players of games” (221–22) fairly crumbles in today’s game market—especially with a title like Ever, Jane, which positions the collective creation of stories as the primary set of gameplay events.

Ever, Jane is not the only video game, it should go without saying, to make use of both narrative and game elements, but Ever, Jane is supremely self-conscious in doing so, conflating them with a deliberate and strategic irony that remarkably approximates Austen’s. Its disruptions underscore how gender stereotypes have so often informed what have been proffered as neutral definitions. As it turns out, however, the performance of gender and sexuality in Ever, Jane ushers in yet more fraught debate, as players prove the idea of there being no room for sex in Austen’s novels a lie. A small but loyal fan-base has been enthusiastically telling stories and building Ever, Jane’s online community for nearly five years now and remaking the reputation of decorous Jane.

Tyrer tells Conditt that she initially conceived of Ever, Jane as a product appealing to female players and expected it to attract women who enjoy literature, many of whom might not have played video games before. A number of the game’s regular players are women (or say they are), but not all. The regular players are actively remaking Austen in the image of modern cultural realities, identifying as female, male, and transgendered players and/or characters. Emily Gera quotes one player, identifying as a thirty-seven-year-old male from Philadelphia, who has created several alter-egos in the game, including a “young, gay former opera singer.” The player continues, “My characters have experienced sweet and tender poetic courtships, hot seductions, shame, and subtle triumphs.” Similarly, before her interview with Tyrer, Gera plays through as “Flopsy McCanada,” a girl from the colonies who is “single and ready to mingle,” and not just with other player-characters; she admits an attraction to the NPC, Shepherd Brimley. Tyrer laughs when Gera mentions it, responding, “We have many players trying to lure Shepherd Brimley into matrimony.” Well, that’s one way to put it. 3Turn Productions provides a virtual world that aims to reflect Austen’s portrayal of Regency social norms, but player-fans exercise considerable creativity within that world, telling stories that are Austen-like, if not entirely Austen-appropriate.

Story introductions provided by the development team are intended as anchors for new players. These provide prompts, but not limits. If selecting a female avatar, players will arrive at school having been callously shoved into a coach by a negligent chaperone. If a male avatar, players arrive at school eager to try out the tavern as soon as possible. After that players can, and do, exercise license, and although Ever, Jane does not offer a non-binary gender avatar, the focus on role-playing in story creation, rather than in first-person combat, results in player-created story arcs that perform gender and sexuality in interesting and often subversive ways. With the rapid turn to “sex play,” 3Turn Productions has designated a separate server, “Botany Bay,” for players who may wish to reenact content that includes displays of sexuality that, because not typical of the original Austen material, could interfere with immersion for other players.

For smaller groups, private chat windows offer another venue for illicit material. Tyrer explains to Conditt that 3Turn Productions did not mean “to make a sex game” but adds, “we also don’t want to ignore the reality: it’s in every MMO that’s out there.” As Tyrer knows, in spite of its pretence of decorum, playing with gender, sex, and sexuality is a huge part of Ever, Jane’s appeal, especially for the regular players. Much occurs behind closed doors, either in the private chat window or on the segregated server, with the players’ imposition of desire in Ever, Jane’s simulated Regency village suggesting how well Austen’s novels lend themselves not just to the typical MMO “trash talk” but also to the typical MMO sex banter. Providing support for this content while nodding to the norms of polite Regency society is just one more way in which Ever, Jane subverts by saying, or doing, two things at once. Player-fans are only too happy to fill in the gaps, and to imagine the stories Austen did not reveal.

Finally, in filling those gaps, the player-created story arcs work to dismantle distinctions between romance and erotica. Note that the word “action” can colloquially mean “having sex,” a meaning that also combines sensori-motor skill with social interaction. In Ever, Jane sex banter is a seamless extension of the vividly realized romantic relationships that mimic period plots. The segregated server or private window marks an apparent division, but the story content flows across the virtual spaces so that romantic and erotic expressions appear in the public and private venues alike. Romance and erotica cannot so neatly be tucked into separate categories, as theorists like Janet Radway have demonstrated. Radway’s pioneering study of the Harlequin romance challenges associations of gender and genre by exploring how romance readers are engaged in a form of extended foreplay that is at once emotional and sexual in cadence, a state of expectation or arousal that culminates, according to the Harlequin formula, in marriage (86–97). Linda Williams extends Radway’s argument, suggesting that the only difference between the melodrama, a genre associated with women, and pornography as a male-oriented genre is the direct portrayal of sex acts; otherwise, they are mirror images (267–70).3 Ever, Jane’s hybridization of Austen narrative and MMO shenanigans makes the shared content of romance and erotica visible, erasing the line between them. Perhaps Rudyard Kipling’s commentary is more apt than Fitzgerald’s: “they’re all on the make, in a quiet way, in Jane” (qtd. in Gilbert and Gubar 111).

![]()

In being at one and the same time both a literary adaptation and a video game, and yet stereotypically neither, Ever, Jane undermines many of the assumptions—which we might, with stronger phrasing, term “lies”—concerning gender, genre, and the author herself. As an adaptation of Austen’s novels, Ever, Jane is further from the actual plots than any of the films, borrowing only the Regency setting, the emphasis on social events, and the author’s name, all while facilitating non-canon content. As a video game, it offers none of the visceral gore of typical MMPORG titles, no progressive rewards of stronger armor or bigger weapons, no end-game boss to defeat, no “killing things.” Where does this leave us? How does Ever, Jane’s marriage of material bring us to insight regarding Austen’s work or video games in general? Importantly, Ever, Jane’s strategies of subversion cut in two directions. Ever, Jane’s disruption of assumptions in game studies brings us back to the fundamental interrogation of links among gender, action, and stories already at play in Austen’s novels. Similarly, the ways in which Ever, Jane dismantles preconceptions about Austen and what her novels are about bring us back to debates in game studies that rage because of inherently unstable tenets and/or definitions. As with so many of the odd couples Austen depicts in her novels, it is a mutually eye-opening match.

NOTES

1For a niche indie game like Ever, Jane the “buzz” generated by articles, interviews, and video reviews is nothing short of a coup. IGN has 12 million subscribers to their YouTube channel alone, and, as IGN’s anonymous vlog reviewers note, this game is not their usual fare. Interviews with Tyrer and reviews of the game have appeared in e-zines and gaming blogs like Engadget, Kotaku, CNET, TheMarySue, MMOs.com, and Game Informer, as well as publications like the UK’s The Guardian.

2My guess at the cause of death: a routine morning walk that had given way to sniffles, followed by pneumonia (certainly not because she had turned into a zombie).

3Mainstream MMOs serve rather to reinforce the division, offering few if any plots that include romance, while female players often complain about the (uncontextualized) sex banter and view it as a symptom of the male-dominated gaming environment.