While this essay introduces a previously undiscovered short story by Louisa May Alcott, the larger context is abolitionists’ deliberate use of the traditional phrase “pride and prejudice.” Examples from a list too large to recapitulate included Thomas Clarkson, William Lloyd Garrison, Methodist Bishop Gilbert Haven, the formerly enslaved Jermain Wesley Loguen, Harriet Beecher Stowe (quoting Edward Gibbon), the poet John Greenleaf Whittier, and Unitarian minister Joshua Young, of Burlington, Vermont, who prayed over the body of abolitionist John Brown after Harper’s Ferry.1

Obviously, the most effective popularizer of the phrase in the long run was Jane Austen, who chose it as the title of her most popular novel. However, “pride and prejudice” had appeared in print hundreds of times before Austen’s novel in 1813. In addition to approximately a dozen examples previously found by scholars, there are at least 240 other published uses of the phrase, not counting variants, by as many individual authors, before Pride and Prejudice.2 That they have gone under-discussed has led to past underestimation of Austen’s seriousness; the popularity both of phrase and of author has a depth that has gone partly camouflaged—by Austen’s ironically self-deprecating “little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory” (16–17 December 1816), among other factors. Examples dating from 1610 through 1812 can be found in religious writing, politics, fiction, and poetry.3 This discovery reveals greater resonance of the title and further reason for Austen to choose it.

One weighty reason for Austen’s choice was the linguistic trend of using the phrase to oppose slavery. By Austen’s lifetime, use of the critique “pride and prejudice” not only to support denomination, faith, or ethics but to oppose enslavement and the slave trade was already established. It was used explicitly to condemn slavery, and many of the authors who used it even in other contexts were abolitionists.4 When Austen in 1813 applied it for the first time as a book title, she married English Regency fashion to the crucially earnest social cause of the time, joining a train of writers also using the phrase who supported social reform generally and abolition and emancipation specifically. This paper joins later American writers Frederick Douglass and Louisa May Alcott in the train with Austen, who, I argue, passionately opposed enslavement.

Like Protestant clergy who used the phrase in the seventeenth century; like translators of French books into English who used it in the eighteenth century; like admirers of Jane Austen who used it in the earlier nineteenth century; abolitionists before, during, and after the Civil War formed social and editorial networks using the traditional phrase as sign and signal. The slavery system itself was consistently associated with the individual or cultural attributes of pride and prejudice; the attributes of pride and prejudice were held to cause slavery, or to stem from it, or both; and condemning slavery and its attributes by using the exact phrase “pride and prejudice” became an abolitionist hallmark (Burns).

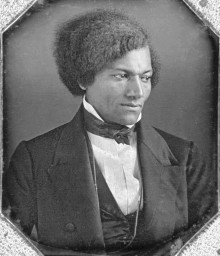

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass

Prominent among the abolitionists using the phrase was Frederick Douglass, who as orator, author, and newspaper editor used it repeatedly and consistently from 1848 through 1883. Douglass’s life and work have been extensively written about by historians and others. Recent books include David Blight’s authoritative biography, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, and Manisha Sinha’s Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, which deals extensively with Douglass as abolitionist leader. Douglass’s use of the expression “pride and prejudice” has not, however, been often examined.5 Such different individuals and entities as Mathew Carey, Thomas Clarkson, and American Whigs had used “pride and prejudice” in opposition to slavery.

The energetic, heroic Douglass relied on it consistently, harking back to it in speeches, articles, and correspondence before, during, and after the Civil War. Douglass’s usage is one of the continuities between antebellum opposition to enslavement and the work of Reconstruction.

Douglass’s own newspapers were a frequent vehicle; the newspapers, archived in the Library of Congress, yield examples of the exact phrase through 1874.6 Both Douglass’s own writing and speeches and those of office holders and other sympathetic correspondents contain many occurrences. Alongside the exact phrase, furthermore, the papers referred to “prejudice” more than a thousand times; “pride” hundreds of times; and both words on the same page more than 400 times.7 Close variants also appear from the earliest issues to the last.8

Three notable examples spanning four decades illustrate the usage. In 1848, Douglass used the phrase in a letter to Horatio Gates Warner (1801–1876), editor of the Rochester Courier newspaper. At the time, Douglass and his family lived in Rochester, New York, where Douglass published his North Star newspaper—later Frederick Douglass’ Paper—and where his home and office were stations on the Underground Railroad. Returning from a trip, Douglass discovered that his nine-year-old daughter Rosetta, attending the private Seward Seminary, had been separated from the other students and was being seated in a different room. When Douglass moved to take his daughter from the school, the school principal, Julia Tracy, then quizzed the other students individually about their willingness to have his daughter there, assuring them that if even one objected, Rosetta would not be taught with them. All the children supported her staying—even under pressure, as Douglass pointed out in his letter. Presumably chagrined, Tracy then took the remarkable step of directing the students to ask their parents whether they approved of allowing Rosetta Douglass to be taught with the others—assuring them, as she had told the children before, that if even one were opposed, the child would be excluded. The only parent opposed was Horatio Warner.

In response, Douglass wrote Warner a touching, stinging letter. Narrating the events outlined above, he closed with an emphatic declaration, “But I do not wish to waste words or argument on one whom I take to be as destitute of honorable feeling, as he has shown himself full of pride and prejudice” (488). Soon after, Douglass published the letter in his North Star newspaper, and William Lloyd Garrison reprinted it in his abolitionist paper, the Liberator.9 The letter was one of Douglass’s more personal uses of the expression and may have been his earliest use in print.

Twelve years later, in December 1860, in Douglass’ Monthly, Douglass reported “Equal Suffrage Defeated” in New York State. The state law on the books required Black men, but not white men, to have $250 worth of real property before they could vote. When the legislature failed to reform the law, Douglass criticized the “triumphant party,” meaning newly elected Republicans, for supporting equality less zealously than the Democrats supported “slavery and oppression” (“Equal Suffrage” 369; Burns). The last election had been tainted and compromised; as a poll watcher, Douglass saw “white men, native and foreign, . . . brought to the polls so drunk, that they needed support on both sides while depositing their votes.” Their “only political principle seemed to be injustice to the negro.” Failing to protect the vote for former slaves and other free Blacks was “an act of unmitigated pride and prejudice, intended to depress and degrade a class which, of all others in the State, need the ballot box as a means of self-elevation and popular regard,” Douglass wrote. The national Republican Party’s putting Abraham Lincoln into the White House did not much help abolitionists in New York (Blight 325–26). As in many such passages, the single terms “pride” and “prejudice” appear repeatedly alongside the intact phrase.

Occasions to apply the phrase did not end with the Civil War or with emancipation or even with the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments. A third Douglass example dates from October 1883, when in United States v. Stanley, the U.S. Supreme Court drastically weakened the fourteenth amendment by declaring the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional.10 The federal law of 1875 had attempted to prohibit discrimination in privately owned spaces of public accommodation, as in transportation, hotels, and restaurants. The effect of the ruling therefore was to strike down federal protection for former slaves and other people of color—and for women, as Douglass mentioned—against discrimination on trains, in hotels, and elsewhere in commerce. From the ruling stemmed decades of restricted accommodations within states. In his October 22 “Address at Lincoln Hall,” Douglass excoriated the decision. The address ranged beyond racial inequities.

Color prejudice is not the only prejudice against which a Republic like ours should guard. The spirit of caste is malignant and dangerous everywhere. There is the prejudice of the rich against the poor, the pride and prejudice of the idle dandy against the hard-handed workingman. There is, worst of all, religious prejudice, a prejudice which has stained whole continents with blood. (Life and Times 661–62)

He went on to observe that while Irish Catholics often harbored vehement prejudice, England was culpable for its “injustice and oppression” toward the Irish.

The references to class and to religion as well as to race were typical of Douglass, who consistently opposed a motivation of prejudice against any targeted group and frequently referred to treatment of women and others besides African Americans; the motto for his North Star paper was “All Rights for All!” Like earlier factions using the expression later made global by Jane Austen, he used it as part of a rhetorical platform to support social justice that expanded the grass roots, to free large segments of the population from everyday oppression as well as from enslavement. The critique of “pride and prejudice” applied to anything that obstructed social justice. Despite the negatives in the phrase itself, and notwithstanding its narrow origins in sectarian branches of British Protestantism in the early seventeenth century, for Douglass as for his linguistic forebears it came to be sign and signal of an enlarged and progressively more inclusive perspective, oriented toward a wider horizon. Not one to let good words go to waste, Douglass republished most of the “Address” in his revised third autobiography in 1892.

Several abolitionists linked collectively by the phrase were individually close to Douglass, such as New York Congressman Gerrit Smith, a Liberty Party member and supporter of the Liberty Party Paper that merged with Douglass’s North Star to create Frederick Douglass’ Paper. On January 18, 1854, Smith had risen in the House to oppose war with Britain.

Let not these appeals, which are made to our higher nature—to all, that is pure, and holy, and sublime within us—be overborne by the counter appeals, which are made in the name of a vulgar patriotism, and which are all addressed to our lower nature—to our passion, pride, and prejudice—our love of conquest, and power, and plunder. (Speeches 14–15)

Smith cited and praised Douglass on the House floor several times and published his admiring “Letter to Frederick Douglass,” Aug. 28, 1854, in his collected speeches.11 In their mutual alliance, Douglass printed Smith’s letters and speeches in his newspapers and referenced him publicly at abolitionists’ gatherings; he further chronicled Smith, admiringly, in his third autobiography.12

At the end of the Civil War, Congressman William Darrah Kelley of Pennsylvania used the same language (5–27). Like Douglass in 1860, Kelley in 1865 supported equal voting rights for Black and white men. Kelley’s rhetorical ploy was to represent discriminatory measures—represented in Congress as reconciliation--as a retroactive defeat. “Let not, I pray you, the South achieve her grandest triumph in the hour of her humiliation. Let not the spirit of a prostrate foe practice on our pride and prejudice, and exult through all time over a lasting victory” (23). Kelley’s speech was published with speeches by Douglass and by Wendell Phillips, another Douglass ally. “Pride and prejudice,” having been a hallmark of abolitionism, was a hallmark of Reconstruction.

If Douglass was the most prominent American abolitionist to use “pride and prejudice” in critique of enslavement, in this linguistic detail as in other ways, he was aligned with the other abolitionists and of course with his own followers, supporters, and allies. The trend was so established for more than a century as to constitute a linguistic phenomenon. That it became forgotten after the nineteenth century may constitute another linguistic phenomenon.

Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott

Among contemporaneous abolitionists using “pride and prejudice” were New England’s Universalist Unitarians—including, I believe, the young Louisa May Alcott. Although the short story published in the Universalist Union weekly and titled “Who Is the Lady?” has yet to attain the status of footnote to history, it deserves examining. Notwithstanding the title, the six-page story was not a suspenseful thriller about a mysterious lady. It had a simple point—perpetually dear to Alcott—that true gentility consists in enlightened behavior rather than in elevated birth or status. The main characters are the nineteen-year-old Fanny Sheldon and Alice Mandeval, the former a worthy farmer’s daughter and the latter a wealthy 1847 uptown girl, “very aristocratic in her ideas of persons and things” but nonetheless fond of the “truthful and intellectual” Fanny. The narrative indicates cryptically that the two are cousins: “Fanny Sheldon had been on a short visit at her wealthy uncle’s . . . , where she became acquainted with Alice Mandeval, an only daughter and an heiress” (349).

The story line is typical for nineteenth-century heroines, tasked with choosing whom to marry among too few or too many options. The leading men are Fanny’s oldest brother, James, a worthy young man whom Alice’s mother calls a “country clod-hopper,” and a wealthy but melancholy orphan named Augustus Horton. For anyone who has read Little Women, the outcome for the two attractive young women is predictable, though perhaps it was less predictable in 1847. The phrase “pride and prejudice” appears near the end.

Mrs. Alice Sheldon is reaping the reward of her courage and fortitude, in giving up vanity, pride and prejudice, and attending to useful and ennobling duties, for thereby it has been in her power, when fortune and friends deserted her parents, to offer them a pleasant and quiet home, with her and her husband. (365)

Demonstrating that the expression is not accidental, a close variant appears on the previous page.

James Sheldon was attracted by the beauty of Alice, but when he saw how selfishness and indolence ruined her, he would not allow himself to love her, but when her better nature triumphed, and he saw her slowly, but surely, overcoming prejudice and pride, and applying herself to useful employments, he loved her, and had the happiness to know that she loved him in return. (364)

The fiction is dated at bottom “Millington, Conn., Feb. 1847” and is signed “Louisa” (366). I believe it to be an unknown short story by Louisa May Alcott. The major counter argument is Alcott’s age, since she would have been only fourteen at the time. I believe, however, that she could have composed this simple story, probably guided by her father and by her reading. She had been attempting plays since the age of ten; for this early story, her literary models were not Shakespeare or “lurid” gothics but the novels of Jane Austen (Stern xi–iii).

Numerous details play into the analysis leading to this conclusion. While the external evidence is indirect, there is no question that Louisa Alcott and her family were embedded in New England’s Unitarian networks, comprising numerous authors and editors who disseminated their views in books and periodicals and were staunchly opposed to slavery and generally supportive of women’s rights. The weekly Universalist Union, which published this short story—the year before Douglass’s letter to Warner—later became Onward, the “Official publication of the Universalist Youth Fellowship.” Its three editors were antislavery Unitarians William Stevens Balch, Otis Ainsworth Skinner, and Salmon Cone Bulkeley.

Connections to the extended Alcott family were a given. Among the likeminded writers published in the weekly was Dr. William Andrus Alcott, a second cousin of Louisa’s father, Bronson Alcott. A similar periodical, the Universalist and Ladies’ Repository for 1838–1839, carried several pieces by Dr. Alcott, “Notices” praising sermons delivered by Skinner, and favorable listings for a Sabbath School book by Skinner and Balch. The religious, social, and editorial relationships lasted well beyond the Civil War. When Balch died fifty years later, the tribute at his funeral was delivered by Universalist pastor A. N. (Ahaz Nicholas) Alcott, an uncle of Louisa, and the admiring biography of Balch recording Alcott’s praise referred several times to Skinner, with whom Balch had studied.13

Naturally, these networks intersected with Douglass. Douglass’s third autobiography contains a rather cryptic reference indicating that he had visited Bronson Alcott’s Brook Farm, where he had known Charles A. Dana, Lincoln’s Assistant Secretary of War (Life and Times 353). The paths of the Alcott family and Douglass often crossed in print, in the directories, biographical reference works, and books and periodicals by Unitarian and other abolitionist authors discussing antislavery history. In 1843, the names Bronson Alcott and Frederick Douglass both appeared on the long list of “Associate Corresponding Secretaries” in a new translational Society for Universal Inquiry and Reform, opposed to enslavement (“List of Officers” 311). One of the Vice Presidents was Lucretia Mott, the Quaker abolitionist and feminist who participated in the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention with Douglass. In the 1850s, Bronson Alcott and Douglass appeared on the same lecture circuits, at least in locations where Douglass could appear. Between the 1840s and the 1880s, predictably, the same editorial and religious networks carried listings and reviews for Louisa May Alcott’s books, with evident pride at the literary popularity of one of their own.

Among Alcott’s fans would seem to have been Douglass himself, if his newspapers are an indication. The papers had already featured Bronson Alcott and his relative Dr. William Alcott in the 1850s. Bronson Alcott’s lecture appearances, for example, were publicized in the North Star in 1850: “Mr. A. Bronson Alcott of Boston, proposes to deliver seven lectures in New York, the coming winter, on certain individuals whom he takes to be peculiary [sic] the representative of New England character and genius.” Predictably, the listed geniuses included abolitionists Dr. Channing and William Lloyd Garrison.14 In 1852 the renamed Frederick Douglass’ Paper announced Dr. William Alcott’s latest book of sermons in highly favorable terms.15

Given that not all issues of Douglass’s newspapers have survived, the likelihood is that they contained more references to the Alcott family than remain in digitized archives. Even the surviving issues of Douglass’s later New National Era, published in Washington, D.C., contain several references to Louisa May Alcott.16 A particularly striking example appeared in 1872, an address supporting “equal rights,” from the Meeting of Republican Women in Boston. Sixteen women signed the address, “in behalf of the Republican women in Massachusetts,” including Louisa M. Alcott, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Julia Ward Howe, and Lucy Stone.17 In 1873, the paper announced Louisa Alcott’s new novel, Work, praising it highly for among other things the “great soul passion of the author running through the whole like a golden thread.”18

Interactions between Douglass’s networks and the Unitarians aligned with broader interactions between abolitionists and organized religion. In Britain and in America throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, while religion was not the sole source for abolitionists’ use of the phrase, the frequent references to pride and prejudice by churchmen ran alongside the intensifying association of the phrase with enslavement. The theological associations overlapped and partly aligned with the political associations of abolitionism. The qualities of pride and prejudice were condemned by clergy in Britain, repudiated by the Episcopal church in America; the phrase “pride and prejudice” as byword for enslavement had religious roots, regardless of how close individual British or American abolitionists stayed to those roots. Surely Douglass himself inherited the expression from both abolitionism and religion—and from both rather than directly from Jane Austen.

Alternative abolitionist and literary precedents, like abolitionist and religious precedents, were not a rigid either/or. As with Louisa Alcott, one could inherit from both. In my view, the short story “Who Is the Lady?” was influenced by both abolitionists and Austen. The internal evidence is persuasive, first in connection with Alcott’s adult novels and then with Austen. The story contains several delicate similarities to later Alcott works including Little Women, and the thematic dichotomies emphasized have repeated parallels in Alcott’s novels and are in fact typical of Alcott. Within its short six pages, the narrative reiterates an unequivocal preference for country over city and for honest work over either money-grubbing or wasteful idleness. The religious references, also typical of Alcott, repeatedly boost a cheerful and non-aggressive piety, opposed to gloom or bigotry; an everyday devotion is upheld, emphasizing genuineness and simplicity.

Like Alcott’s novels, the story repeatedly blesses love of music and love of poetry, inserting quotations from poetry into the narrative; and love for the (genuinely) finer things of life is situated in a pleasant farmhouse, simple but well-maintained. As in Alcott’s novels, autobiography plays a role. The character Fanny Sheldon is said to “write some for the periodicals”; “Indeed, Fanny, the eldest daughter, had written, under an assumed signature, for various periodicals,” as did the young Louisa Alcott herself (349, 350).

The thematic dichotomies of the story also align with an ongoing doctrine of taste—meaning good taste—that prescribes simplicity over finery, naturalness over artifice, and usefulness over uselessness. Predictably for anyone who has read Alcott’s novels, “Who Is the Lady?” endorses innate good sense in fashion as in theology. When Alice with unintentional vulgarity compliments Fanny on being well dressed despite living in the country, Fanny clarifies that “that is quite an easy thing here in the country, Alice, where fashion is not so blindly worshiped as in the city” and where “we use our own powers of reason and taste, without depending upon foreign mantua-makers” (349). Simplicity and modesty characterize the festive preparations for the wedding, which like Meg’s in Little Women takes place at the family home (365). As with Alcott’s full-blown novels, the story could be called “preachy,” but the central purpose and ideas come through clearly—life lessons for young women, mostly affirmative.

The characters resemble later Alcott characters. Augustus Horton resembles Laurie in Little Women—well educated, sensitive, intelligent, and affectionate, drawn un-snobbishly to an unglamorous heroine. Alice especially resembles later characters—a pretty girl, spoiled in childhood, reforming as she matures. Like Meg, Alice learns to live cheerfully without luxuries she was previously accustomed to; like Amy, she develops a more genuine sophistication—though the story does not call it that—in thinking about things other than fashion and admiration. She also leaves behind reading trashy novels to take up everyday household duties.

Alcott’s earnest books are not often associated with Austen’s, especially with Austen’s light, bright, and sparkling Pride and Prejudice. But the elements familiar in Alcott’s novels are also familiar in Jane Austen’s. In fact, they are also typical of Austen, and similarities to the adult Louisa Alcott overlap influences from Austen. Austen’s Mansfield Park and Pride and Prejudice especially loom over the story. Fanny Sheldon is described as having “a polite, yet unassuming dignity in her manners” (349). Like Fanny Price, she is a loved elder to her younger siblings; “she was their kind sister, their affectionate friend in trouble, their dear instructer” (350). (Even the misspelling is an appropriate homage to Austen, if unintended.) Both “Fanny” and “Alice” are character names in Mansfield Park; the latter is the name of an offstage character and a name not favored by Austen.

As in Pride and Prejudice, the author begins the fiction with dialogue caught in medias res, filling in the story and the backstory later. Somewhat like Bingley’s sisters in Pride and Prejudice, Alice “had forgotten, if she ever knew it, that her father was once poor, and had risen, step by step, to the high place which his wealth had assigned him in society” (349). Alice’s father is financially stressed, like George Wickham’s father, by the “extravagance of his wife” (365). Like several Austen heroines, however, the Alice in the short story redeems herself; a social humbling leads her to draw enlightenment from the moment and resolve to reform (350). The incident aligns with the broader question raised in the title of “Who Is the Lady?” which is addressed explicitly and implicitly throughout Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park—and in Austen’s other novels.

At moments the suggestions of future Alcott and past Austen draw close together. Early in the story, Alice’s father, like an Alcott father figure “look[s] only at true merit and nobleness of character, as elevating to their possessor”; the daughter, like an Austen secondary character, holds “the idea that no person who labored for a living, could be possessed of any refined feelings” (349). At other moments the diction draws closer to Austen’s, as when the narrator describes the Sheldon family: “Though they were not versed in the conventional forms of fashionable society, yet they were not lacking in dignity, ease, or politeness” (350). Alice’s mother disparages James, but she “still could not deny that he was handsome and intelligent; and if he had only worn the requisite quantity of hair around his countenance, would have been quite passable” (365).

If Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park are main ingredients, the story may have a dash of Northanger Abbey. Fanny’s oldest brother, James, literary and poetic, enters his father’s occupation, as in Austen’s own family and in Catherine Morland’s. Coincidentally or not, both Austen and Alcott quote lines from James Thomson’s “Spring,” and both miscall him “Thompson.” “Who Is the Lady?” ends by saying, “Thompson’s beautiful picture of quiet domestic life has found a realization” in the married couples, quoting a Thomson stanza. The mistake may have been common, but Jane Austen makes the same error at the beginning of Northanger Abbey, where a tongue-in-cheek catalogue of Catherine’s learning in poetry includes “Thompson” and quotes “Spring,” ten lines above the stanza chosen by Alcott: “It is a delightful task! / To teach the young idea how to shoot” (NA 15). Alcott uses “Thompson” to give a final boost for peaceful rural life, rounding out the delightful task of teaching the young through the story itself—without the ironies of Austen’s presentation.

Beyond Alcott and Austen, the short story raises broader points. In fiction including Alcott’s, ennobling domestic labor had a social purpose beyond just improving women’s fashions or women’s behavior. Both the ongoing critique of style and the ongoing reminders about appropriate conduct had a moral beyond clothes or manners. Calling upon men and women to perform their own domestic labor and not to look down upon labor served the anti-slavery cause. As the negative references to unnecessary consumption and the positive references to farming reminded the reader, doing one’s work oneself reduced reliance on imported goods and reduced purported need for servitude, countering both the profits of the trade and one justification for coerced labor. Again, Austen’s heroines take the same position regarding unnecessary finery.

Not all contemporaneous novelists were antislavery, any more than were all contemporaneous politicians, but those writers who were tended to appreciate Austen. One case in point was the earl of Carlisle, M.P. George William Frederick Howard, who had chaired the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. When Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was reprinted, Carlisle was invited to write a preface. His favorable review ran in December 1852 in Douglass’ Paper. He praised Stowe highly in literary terms, first comparing her to Charles Dickens and then to Jane Austen. “In the tea-table dialogue of the Ohio senator and his wife, and in the self-portraying complaints of Mrs. St. Clare, are we not reminded of our admirable Miss Austen?” Carlisle then went on for two columns to condemn slavery, to restate his opposition, and to voice his support of “the Anti-slavery party in America,” in eloquent and no uncertain terms.

NOTES

1For some instances of the phrase used in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, on both sides of the Atlantic, see William Lloyd Garrison’s 1832 Thoughts on African Colonization (56); Thomas Clarkson’s 1843 “To All Christian Professors” (315); Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1853 Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1:339); Jermain Loguen’s 1859 Reverend J. F. Loguen as a Slave and as a Freeman (181); Gilbert Haven’s 1869 National Sermons (279); John Greenleaf Whittier’s “On a Prayer Book, with its Frontispiece, Ary Scheffer’s ‘Christus Consolator, Americanized by the Omission of the Black Man” in his 1861 Home Ballads and Poems (137). For Joshua Young’s 1859 prayer, see Drew (74).

2This essay draws upon research from a book in progress, “Jane Austen, ‘Pride and Prejudice,’ and Slavery.”

3For a few examples, Joseph Hall’s 1615 Recollection of Such Treatises (572); Daniel Defoe’s 1708 “Review of the State of the British Nation” (91); Charlotte Turner Smith’s 1800 “Eliza and Emma” (54); Thomas Ashe’s 1812 Liberal Critic (3.295).

4Among many examples, Guillaume Raynal’s 1776 Philosophical and Political History; William Russell’s 1778 History of America (2:326); John Newton’s 1786 Messiah (2.364); Elizabeth Hamilton’s 1801 Letters on Education (1: 236).

5ee Mary Favret (400–01) and Burns.

6Douglass’s newspapers comprise North Star (1847–1851), Frederick Douglass’ Paper (1851–1860) with Douglass’ Monthly 1860–1863), and New National Era (18770–1874). Besides the 1848 example of “pride and prejudice,” see North Star 7 Dec. 1849: 2; Frederick Douglass’ Paper 24 Mar. 1854: 2 and 17 Sept. 1858: 2; New National Era 2 Oct. 1873: 3 and 19 Feb. 1874: 1. On the publication of Douglass’s first autobiography and the founding of his first newspaper, the North Star, see Sinha (425–28).

7Exact counts as of March 22, 2021: 1,240 “prejudice”; 792 “pride”; 438 pages on which both terms appear.

8For example, North Star 27 July 1849: 1; Frederick Douglass’ Paper 4 Feb. 1853: 3; New National Era 11 June 1874: 3.

9North Star 2 Sept. 1848: 2 at https://www.loc.gov/collections/frederick-douglass-newspapers; Woodson 488.

10United States v. Stanley, 109 U.S. 3 (1883 U.S. Lexis 928). The high court had consolidated five cases—United States v. Stanley, United States v. Ryan, United States v. Nichols, United States v. Singleton, and Robinson and wife v. Memphis & Charleston R.R. Co.

11In Smith’s Speeches in Congress, “The Nebraska Bill” (196) and “Strike out ‘White’!” (228); in his Speeches “Letter to Frederick Douglass” (401–11).

12Douglass, Life and Times (esp. 230, 232, 268, 283, 356–57, 459–60). On Douglass and Smith’s relationship, see Blight (191, 202, 207–08, 215–17).

13See Andrus Alcott, “The Young Wife,” Universalist Union 3 (1837–1838), 192. And Universalist and Ladies’ Repository 7 (1838–1839), 39, 78, 118, 159, 239, 319, 398, 439, 474; and Holmes Slade, Life and Labors of the Late Rev. William Stevens Balch (Chicago, 1888), 13–14; see also 76, 97, 283, 317, 276.

14“Medley,” North Star, Dec. 5, 1850, 1.

15“Literary Notices,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, April 29, 1852, 2.

16For example, notices of her latest short stories on Feb. 26, 1874, and Sept. 24, 1874.

17“The Women in Council,” New National Era, Oct. 3, 1872, 3.