Although in no way the “start” of the current COVID-19 pandemic, in March of 2020 many U.S. university campuses moved their classes online as regional quarantine policies responded to the crisis. Acknowledging the level of privilege that allows us to socially distance, we found ourselves relatively safe but physically isolated from our local friends, family, and colleagues. Interpersonal contact, whether personal or professional, moved almost exclusively online. For some, a less-geographically bound social space prompted them to reach out to those farther away. In our case, midweek game nights emerged, where we opened up Zoom and played online games together.

As time progressed, we were continually intrigued by the Austen and Regency-inspired games we found. We had known that there were games from major studios that used the eighteenth century as a setting or inspiration. After all, we had grown up on the eighteenth-century Caribbean as it is depicted in LucasArts’s Monkey Island series (1990–2010) of pirate adventure games, and we knew that major AAA studio Ubisoft set multiple games in their long-running Assassin’s Creed franchise (2007–present) in the eighteenth century: first the Caribbean with Black Flag (2013), then the American Revolution in Rogue (2014), and the French Revolution in Unity (2014). Outside of these major studios, we’d known of Massively Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Games (MMORPG) like Ever, Jane: The Virtual World of Jane Austen (2016–2020), which shut down in December 2020.

The games we play rarely come from a major studio. Made by independent developers fueled by a love of Regency culture and Austen, these games are aimed at overlooked groups of gamers (including but not limited to women) and showcase their creators’ technical, artistic, and literary skills. Much like Austen’s “bit of ivory,” this wave of games is “small” by the standards of the game industry, but the games are often carefully and beautifully wrought. It is important to note that these games are often created by a tiny handful of people, if not a single creator. They are generally labors of love, not big-budget commercial media ventures. Meanwhile, they are under more structural pressure to be narratively capacious, with scripts that can swell to tens of thousands of words to cover all the narrative options, dialogue variations, and the like. What we have focused on here—the visual impact of character design—is often the costliest component for a new game designer. It is thus not terribly surprising that even in ambitious and progressively minded games, there is a limit on what can be offered. That said, we hope to see still more depth of representation—in image and text—in games in the years to come.

We argue that these games offer an important window into how Austen and her world are perceived by modern consumers. Whether it’s the artful design of a deck of cards in the tabletop Austen roleplaying game Good Society, the accomplishment-honing mechanics in Regency Love (2015), or the different romantic heroes in The Lady’s Choice (2016), these games offer a window into the tastes and values of those who create and play them. Focusing on games produced independently of major studios, we offer our readings as a celebration of the questions they provoke. It’s hard to know precisely what getting representation “right” would entail. But as we see in the conversations around some of the games we describe, there are ways forward to “better.”

These games matter, not only as interpretive works in themselves but because of what they show us about how Austen fan-culture at large grapples with the legacies of systemic inequality past and present. The challenges of representation now playing out in big-budget, mass media film and television screens, in fandom and enthusiast organizations, have been playing out for years in the world of smaller-budget, niche video, roleplaying, and board games. It is arguably easier to see our continued blind spots in the cutting-edge, individual world of indie games. In adapting Austen, what are we prioritizing from these narratives, and how do those priorities shape (or limit) how we talk about Austen and her works?

Representing the Regency

No matter the medium, adaptations signal what a group values in a particular time and place. Comparison allows us to see change over time. Claudia L. Johnson points out the lack of friction between the (upper) classes in Robert Z. Leonard’s 1940 film adaptation of Pride and Prejudice as reflecting calls for wartime solidarity within Britain and across the Atlantic (131–34). Over seventy years later, the multi-platform modern adaptation The Lizzie Bennet Diaries (2013) transformed the novel’s marriage market into job markets. With the exception of Jo Baker’s Longbourn (2013), few adaptations look beyond the scope of the gentry and upper classes. Indeed, when many people picture Regency Britain or think of a Regency romance written today, whom do many audiences expect the narratives to focus upon? Whose stories do we expect to be privileged in the retelling?

This question goes beyond the Regency and reception of Austen’s work. With both the fictional and non-fictional, these representations of the past illuminate what—and whom—those telling and consuming them value in the present. In 2017, the BBC’s animated children’s historical series, The Story of Britain, received criticism for depicting a Roman British family as being of African descent. Although scholars such as Mary Beard and Matthew Nicholls pointed out that this depiction was historically accurate, for some it did not seem accurate because it did not reflect the way they had experienced this historical story before. Similarly, in 2021, there was some pushback against news coverage of recent archaeological work on the Tudor-era ship, the Mary Rose, accusing the Mary Rose Museum and related historical organizations of trying to “cancel history” in order to cater to demands for racial diversity. How we represent the past shapes how many will evaluate the “accuracy” of later representations.

For this discussion, we focus mainly on racial representation. Considering these examples of resistance to historical news involving a more diverse Britain than previous representations had led many to expect, is it surprising that film and television adaptations of British literature have been slow to challenge these preconceptions? As information about the racial identification of actors varies, and racial presentation—what race the actor appears to be in a role—is extremely subjective, we tried wherever possible to hew to the actor’s self-identification. Formerly, film and television adaptations treated race, ethnicity, and the nation of origin of the actor or their family as an adjective to their nationality, which for our purposes is primarily British. Looking at Charles Dickens adaptations, for instance, we see incremental change in terms of racial casting: in 2007, WGBH/BBC cast Jewish-Nigerian British actor Sophie Okonedo as Nancy in Oliver Twist, and in 2008 Iranian-Ghanian British actor Freema Agyeman played Tattycoram in Little Dorrit. But it was not until 2019 that an actor of color was cast in a lead role for a major adaptation with the Searchlight feature-length film, The Personal History of David Copperfield, starring Dev Patel, whose Gujarati Indian parents migrated to England from Kenya. This production used a “color blind” approach more commonly seen on stage. In color-blind casting, no attempt at “realism” informs casting decisions.

This approach is distinct from “color conscious” casting, which refers to the practice of changing what is “traditionally” considered the race of a character as part of a production’s overall interpretation of the material. When asked why he opted for a multi-ethnic cast, Copperfield Italian Scottish director Armando Iannucci presented it as a “natural” choice with some potentially political undercurrents: “I instantly thought of Dev. . . . [H]e has those qualities of naivety, awkwardness, and yet strength at the same time. . . . I couldn’t think of anyone else, I didn’t have a plan B” (McIntosh). On whether the film is a commentary on the current cultural moment, Iannucci simultaneously seems to dismiss and answer the question: “It wasn’t a conscious reaction to Brexit, but the conversation has gone very insular in terms of what Britain is and what it doesn’t want to be. . . . I wanted to celebrate what Britain actually is” (BBC America editors). Whether reflecting it in the twenty-first or nineteenth century, these adaptations offer a more accurate demographic image of the nation, especially of London, than an exclusively white-presenting cast could.

Until very recently, attempts to transform Austen have created a binary between all-white period costume drama or modernized, multiracial adaptations like Bride and Prejudice (2004), From Prada to Nada (2011), the interlocking web adaptations of Hank Green and Bernie Su’s Pemberley Digital (2012–2018), and the miniseries Pride & Prejudice: Atlanta (2019). Aside from modernizations or the 2019 ITV/PBS series Sanditon (in which Trinidadian-Guyanan American Crystal Clarke plays Georgiana Lambe, a character who is explicitly mixed-race in Austen’s unfinished manuscript), little has been done in major Austen adaptations to challenge the myth of an exclusively white Regency Britain. Beyond Austen, this is changing: the 2007 BBC series Taboo featured a multiracial 1814 London, although it cast Irish-English British actor Tom Hardy as the mixed-race protagonist (his mother is from the Nuu-chah-nulth nation in Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island, Canada). Refinery29 adapted Suzanne Allen’s 2009 Regency Romance novel Mr. Malcolm’s List into a short film in 2019 and now plans for a future feature-length film that builds upon its current color-blind casting. Perhaps most notably, though, is the racially diverse casting of the 2020 Netflix hit Bridgerton, which we discuss in the conclusion of this piece.

Although we focus on racial diversity here, this argument applies to questions of representation for sexuality, class, gender, disability, and other identifying categories. The examples given here of television and film are perhaps the most visible examples to the widest audience. Yet, we argue that the issues we see playing out in these high budget productions can be seen also in mediums where smaller creative teams and individual’s work. By looking at indie video game adaptations, we are able to look at what happens when teams of a handful of people, working with little to no budget, for niche audiences, adapt Austen and her world. What we find is that getting representation “right” remains a challenge but that there is an audience for new visions of Austen.

Playing the Regency

When selecting the indie games we discuss here, we sought out ones that were accessible and affordable for most people. These can be played on a regular computer, smartphone, or tablet with no additional equipment. They cost a small amount compared to games from major studios or are made available for free on platforms like itch.io, Steam, and iOS. Their makers often identify as members of traditionally marginalized groups, and their content often reflects it. Unlike big-budget AAA games discussed in our introduction that use eighteenth-century settings to depict military conflict, colonization, or piracy, indie games cover a broader palette. In particular, we found multiple games clearly inspired by Austen, either as direct adaptations, use of Austen references, or their Regency setting.

Although Austen scholars like Linda Troost have been aware of the “gamification” of Austen for some time (Troost 2017), full critical focus has only been recent: Dana Omirova’s piece on Matches and Matrimony (2011) appeared in the Winter 2019 issue of Persuasions On-Line, and Andrea Austen’s piece on Ever, Jane (2016) followed in the next issue. We expand upon their work, giving an overview of the Austen-inspired games that independent creators are producing, with an emphasis on their attention to issues of race, gender, and sexuality. Finally, we will examine two “visual novel” games that attempt to represent a more racially diverse Regency England than many of their counterparts. Much of the critique of Bridgerton points to large corporate studios to account for why efforts to expand representation often fall short; there is truth in this argument. We hold up the case studies of these two games—Northanger Abbey and The Lady’s Choice—as examples of how, even with the best of intentions and without corporate interference, getting representation “right” remains a challenge we are all called to meet.

Some of the games we found hewed closely to what many today assume is a “traditional” representation of the Regency, while others explicitly pushed for greater representation in terms of gender, sexuality, and race. It is important to note that games are not a generic monolith, a fact reflected in the games we discuss here. Austen Translation (2017), for example, bills itself as a “satirical strategy game.” You play a young woman in want of a husband, searching for eligible suitors in competition with your rivals. In the words of the game’s developers, the game is

an Austen experience which has gone completely off the rails. It’s an experience rife with dropping pianos, outrageous rumors, and mercilessly manipulated rivalries. A Jane for the digital ages, as it were.

There is, however, little explicit reference to Austen aside from occasional puns like the character “Hank Crawfish.”

Screenshot from gameplay of Austen Translation

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Instead, what Austen Translation draws from Austen is the social satire of the marriage market. Similar in its borrowing of the visual signifiers of the era, with little focus on narrative, Regency Solitaire (2015) offers a Regency-inspired design for a series of virtual card games based on solitaire. Between rounds, it intersperses a narrative focused on well-born but financially insecure Bella, as she navigates society in Brighton, Bath, and London in her attempt to restore her family’s reputation and find a suitable husband.

Aside from games such as these that borrow the aesthetics more than they produce a narrative about the Regency, most Austen-inspired video games fall under the structural category of “visual novels,” which contain branching narrative structures very familiar to anyone who ever picked up a Choose Your Own Adventure book. Western developers will call them otome (after the inspiring Japanese form), dating simulators (or “sims”), and/or interactive fiction, often interchangeably. Games vary widely in length: the shortest are based on scripts as short as this article and some are longer than all of Austen’s published novels combined, though most writers tend to aim for 65,000–80,000 words (or a little over half the length of Pride and Prejudice). New possibilities are unlocked through dialogue choices, the acquisition of skills or goodwill, or a combination of both. No sophisticated hand-eye-coordination is required, as the games are generally “point and click.” Usually, these are financially accessible, with most of them costing less than $20 USD; several are actually free or offered on a pay-what-you-want basis.

Unlike Austen’s novels, visual novels are rarely designed to be read linearly. Instead, the player/reader makes choices that affect the ending. Collecting all possible endings (and the pathways to those endings) is part of the appeal of the form. For example, the dating simulator game Matches and Matrimony (2011) creates its branching pathways by combining the plots of three Austen novels. While you “play” Elizabeth Bennet, you can follow paths to endings where she marries Mr. Collins, Mr. Bingley, “Mr. Wickeby,” Colonel Brandon, or Captain Wentworth or remains single. There are multiple endings for Darcy, depending on when you accept his proposal. Although Omirova argues that modern game adaptations “have the potential to model female empowerment through individual choice,” we have observed that games inspired by Austen or the Regency vary wildly in their depictions of female agency.

Truths Untold (Crow Tree Entertainment 2020– ), for example, the player names and controls Miss Fernside, who is returning with her parents from an extended trip to the Continent. The Fernsides were investigating the fate of Mrs. Fernside’s first husband, an aristocrat presumed dead during the French Revolution. With the help of family friend Mr. Silas Worthington, the Fernsides discovered that her husband lived much longer than expected, rendering the Fernsides’ marriage bigamous and Miss Fernside and her brother illegitimate. While they are able to keep this information secret, their lengthy trip abroad has led the neighborhood to assume that Miss Fernside was concealing a pregnancy, fathered either by boy-next-door Mr. Guy Linfield or Worthington. To refute the assumption would require revealing her equally damning illegitimacy, destroying her brother’s prospects as well. While Miss Fernside can choose to be “demure,” “composed,” or “rebellious,” her choice is a reaction to plot points she doesn’t control.

Screenshot of gameplay from Truths Untold

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Regency Love (2015– ), a mobile game for iOS, possesses, to the best of our knowledge, the only development team to have presented at the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (BSECS). Players interact with a variety of characters, and choices impact the player’s attributes—dutiful, compassionate, spirited, sensible, or gentle. Through minigames of Austen trivia, the players also improve their “accomplishments” in the areas of dancing, drawing, music, needlework, reading, and riding. These choices affect the ultimate ending of the game and how the player character feels about that ending. The suitors are heavily influenced by Austen characters: Mr. Ashcroft, a wealthy landowner and protective older brother strongly resembles Mr. Darcy, while Mr. Graham’s look and plot seems inspired by Colonel Fitzwilliam. Most strikingly, Mr. Curtis’s appearance is clearly based on Alan Rickman in the 1995 film adaptation of Sense and Sensibility. The last, Mr. Digby, is the default suitor who will always propose marriage, regardless of how you treat him. Designed to look more cartoonish than the other characters, he is a comedic character frequently ridiculed, drawing to mind more harmless and less pretentious failed suitors in Austen’s novels. As with many of the indie games we explored, this game hopes to be expanded with additional romantic options. Despite close female friendships in the current iteration of the game, all the romance options are mixed sex, but in an expansion to a London setting, the development team wishes to include the possibility of a same-sex relationship.

Screenshot of character list in Regency Love

(Click here to see a larger version.

The “historical accuracy” bugbear

Most of these games feature uniformly white character designs: the current iterations of Truths Untold, Regency Love, and the majority of games discussed thus far have only pale, pink characters. Austen Translation allows the player a customizable skin palette, but these choices go beyond the human spectrum into hues such as purple. A proposed interactive novel, “A Regency Tale” by Ishantrissi, was abandoned at the script-writing stage by its creator due to what he called a “lack of ideas for a woman in the regency era.” When it reached the sprite-development stage in 2015, all proposed characters were white—and the developer appears to have received no pushback (“A Regency Tale”). This depiction of people in Regency England uniformly presenting white comes out of a belief that such a population is historically accurate. Before its closure in December 2020, Ever, Jane’s official policy, as of their 2013 FAQ, insisted that it “provide[s] historically accurate racial diversity” but that racial under-representation “only becomes an issue where we get into aristocracy and with ethnicities that had not yet migrated to England.” Yet, although they stand by their commitment to “accuracy” in racial representation, the next sentence pulls back: “If the historical accuracy interferes with the fun of the game rather than adding to it, we reserve the right to decide to ignore it further in development. For now we believe that we can manage these issues and maintain the historical accuracy without conflict” (FAQ).

To be clear: Ever, Jane’s FAQ is wrong. By Austen’s day there had been people of African descent in Britain for centuries, as has been documented by Imtiaz Habib, Kim F. Hall, Matthieu Chapman, Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina, and many, many other scholars. Global trade routes meant that contact and transit also included peoples from the Middle East and across Asia. The British aristocracy had connections across Europe and beyond: most visible in Austen’s day was the heiress Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761–1804), the biracial granddaughter of Sir Alexander Lindsay of Evelick, 3rd Baronet of Evelick, and the ward of her great-uncle, William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield. The loss of the American War resulted in the arrival of the Black Loyalists, formerly enslaved as well as freeborn people of African descent who sided with the British against the North American colonists, largely due to Britain’s promise of emancipation and land. The abolitionist movement of the late eighteenth century included public figures such as the Sons of Africa, a collective of formerly enslaved, politically active, relatively affluent men, such as Olaudah Equiano. Still earlier, Ignatius Sancho voted in elections, ran a grocery with his own brand of tobacco, and became so well-known for his letter writing that an edited volume was published after his death. As we will discuss later, although there is still debate on whether Queen Charlotte’s Portuguese heritage and comments from her contemporaries on her appearance signals that she was of African descent, many Britons today—especially from Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities—view her as such. Beyond those with status or celebrity, there was a BIPOC population that we find mentioned in playbills, parish records, employee payrolls, and more. This brief overview focuses on those of African descent as a sample of the diverse communities within the British Isles. If we were to look at diplomatic envoys, sailors, servants, hairdressers, travelers, children of the gentry (such as the aforementioned Dido Elizabeth Belle or Eliza Raine, the mixed-race daughter of an East India Company surgeon and one of the early lovers of Anne Lister), and others, we would fill volumes.

The historical reality of a multiracial Regency is reflected in the novels of the times. Lyndon Dominque’s timeline of representations of women of color in fiction spans multiple pages in his Broadview edition of the anonymous The Woman of Colour (1808). And of course, the biracial heiress Miss Lambe is a character in Austen’s unfinished novel now known as Sanditon. Yet, when we look to modern Regency romances, period dramas, games, and other current representations of this era, we do not find the stories acknowledging this past. Although we believe that the creators of these works often act out of a sincere belief in a white British past, it is important to note how this myth has been used to harm BIPOC communities today. Since the 2016 violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, public awareness has grown of how far right, white supremacist groups weaponize the past. Whether the detention centers along the US/Mexico border or the UK policies that tried to revoke citizenship from BIPOC people who arrived on the Windrush, the idea of a “return” to a racially pure past rests on the assumption that there is such a thing.

Public scholarship projects such as The Public Medievalist (focused on Classical Studies), and People of Color in European Art History strive to highlight the academic research that counters such misinformation, but it is from popular culture that many people receive their visions of the past. The mistaken conception of a pure, isolated “white” past for Britain and Europe possesses a disturbingly long lineage, as discussed on these sites. A history of this myth of a pre-racial past purported by white supremacist and nationalist groups is documented in the fields of classics and medieval studies; more recently, we have seen the adoption of Austen by some extremist circles. As Nicole Mansfield Wright points out in her piece on the alt-right’s love of Austen, their poorly-argued claims to and admiration for the author go beyond fandom into a means to normalize their ideology: “By comparing their movement not to the nightmare Germany of Hitler and Goebbels, but instead to the cozy England of Austen—a much-beloved author with a centuries-long fandom and an unebbing academic following—the alt-right normalizes itself in the eyes of ordinary people” (Wright). Countering this ideology should not be viewed as controversial but a call to action. One way to combat the far right’s appropriation of Austen is to create a space for a multi-racial vision of her world. Although we do not know or argue that creating such a space is the intent of the game designers that we highlight in the next section, we do interpret them as part of the antidote for a toxic framing of Austen, the Regency, and British identity.

Designing diversity: two cases

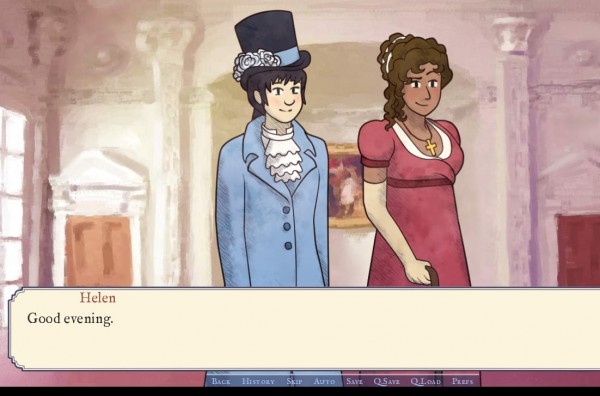

Two games attempt to reflect a multiracial Regency Britain: Northanger Abbey (2016) and The Lady’s Choice (Jenkins 2016). Both integrate BIPOC characters into their representation of Regency England. Perhaps the closest to a conventional adaptation of its source material, Northanger Abbey offers three main narrative options: to proceed in “the same manner as the original novel,” “in a manner of my specific choosing,” and “surprise me!” Depending on the paths chosen, your character may identify as Catherine Morland (as in the novel), the male-identified Christopher, or the non-binary Kit. These choices concerning gender presentation mainly manifest in which of three outfits they wear: a blue muslin dress, a blue Regency suit, or a “flower bedecked top-hat and long [blue] androgynous coat.” In terms of physical appearance beyond clothing, the player chooses how they are perceived: is their figure “thin and awkward” or “lithe and delicate”; their skin “sallow and without colour” or “ethereal and golden”; or their hair “dark and lank” or “like a river of ebony.” These are decisions about self-perception, not visual difference: choosing the “negative” traits results in a humble personality perceived as lacking confidence; “positive” leads to confidences perceived as vanity; and a mix creates a balance of humility and confidence. Regardless of which main narrative option is chosen, the player retains agency over shaping Catherine (or Christopher or Kit), but within the framework of the marriage plot. Here the player’s choices can alter Catherine’s “personality traits,” relationship with other characters, and “in the end, . . . may find love or friendship with Henry Tilney, his sister Eleanor Tilney, or no-one.”

Screenshot of gameplay from Northanger Abbey in the gender-flipped version

(Click here to see a larger version.)

In all of the options of whether to take the conventional, self-directed, or surprise path, race is overtly noted for the protagonist: regardless of what choices of gender, sexuality, or appearance are made, the protagonist possesses “East Asian features.” Beyond background chinoiserie similar to what we see noted in Austen’s novels and this basic categorization of the protagonist’s “features,” the racial marker remains unremarked upon for the majority of the game.1 That the protagonist has an “East Asian” appearance that arguably makes no difference to the game offers a means of adding wider racial representation to the player’s conception of the Regency. At the same time, much like the way appearance is tied more to self-perception than to concrete visual attributes, Catherine’s race prompts the player to examine their own perceptions: do they search for a new interpretation of the text in light of this information? Do they resist out of a reactionary notion of historical “accuracy”? Do they shrug and keep playing?

Background images from Northanger Abbey (left painted, right rendered)

(Click here to see a larger version.)

The game’s ambiguous presentation of race is woven throughout its retelling of Northanger Abbey. Choosing to proceed in “the same manner as the original novel” includes the characters, major plot points, along with quotations from the novel. Yet in all of the narrative options, the race of the characters is largely up to the interpretation of the player. Does Henry Tilney’s noticeably darker skin tone act as a racial signifier?

Northanger Abbey’s option to proceed “in a manner of my specific choosing” allows for what the game refers to as “the most dramatic choice: the nature of society itself,” in which the player decides whether their particular Regency is a patriarchy or matriarchy. Rather than an imagined space of gender equality, in the matriarchy “all female characters become male, and vice versa, and assigned genders are switched similarly.” It is within this path, that the player has the most freedom of choice in terms of “genders and gender presentations.” Yet, even within the pretense of choice, there are limitations. Presenting as female or male determines with whom you dance; only the non-binary option avoids what Adrienne Rich termed “compulsory heterosexuality.”

Appropriate to an Austen-inspired piece, the narration is free, indirect, and wry. Asides speak to the nature of the game play and genre. This tone perhaps accounts for the play of the sexual and racial determinism of the game with the genre’s emphasis on individual choice. A player may choose to be non-binary and/or to be supported by their parents, but ultimately the world of the game will label them. Dancing with a gender-swapped Helen Tilney (listed as a priest rather than clergyman) leads observers to label the non-conforming Kit as male. The power to change the narrative lies with how non-player characters (NPCs), the protagonist, and the player view the central Morland. In Northanger Abbey, we thus see the way that self-perception and questions of identity can shift the shape of a well-known story. In Spring 2021, the creator Spiral Atlas released a free demo of a new game, Pride or Prejudice, based on Austen’s 1813 Pride and Prejudice. As with Northanger Abbey, this as yet unfinished project adheres closely to the original text but with a greater degree of player control of how their “Elizabeth” Bennet appears in terms of coloration, clothing, physical build, and whether they use a modern wheelchair. How these modifications will fit into the finished adaptation remains to be seen.

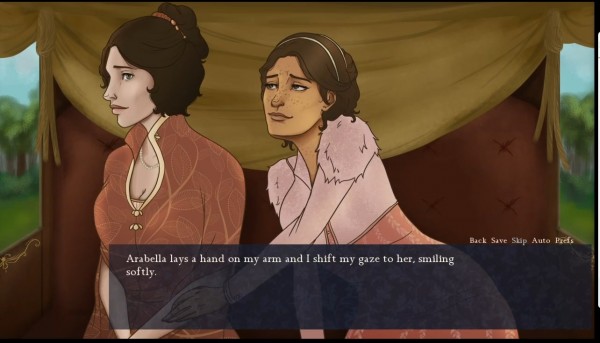

Despite not being an explicit adaptation of Austen’s work, The Lady’s Choice (2016) is very much indebted to that author. It is (at the time of writing) the most visually diverse of any Austen-inspired game we have encountered. This diversity perhaps goes hand in hand with the way it is described by its designer: “Though it is a historical visual novel, it’s not going to be completely accurate (for example, they didn’t really have a Season in Bath). I have taken liberties because, well, I wanted to have fun with this rather than freak about every nuance of historical accuracy.”

In The Lady’s Choice, you name your heroine, who is pale with dark brown hair and blue eyes. Accompanied by your widowed friend Arabella, you are embarking upon a Season at Bath. At your first ball you meet Isaac, Lord Stanton, Captain Guy Blake, and Lord Laurence Amesbury, along with other supporting characters. Your decisions about dialogue place your character on a path to one of four possible endings with each love interest, or establish your personality as “genial,” “headstrong,” “witty,” or “sensible”—and different suitors are attracted to different personalities.

Screenshot of gameplay from The Lady’s Choice: heroine and Arabella in a carriage

(Click here to see a larger version.)

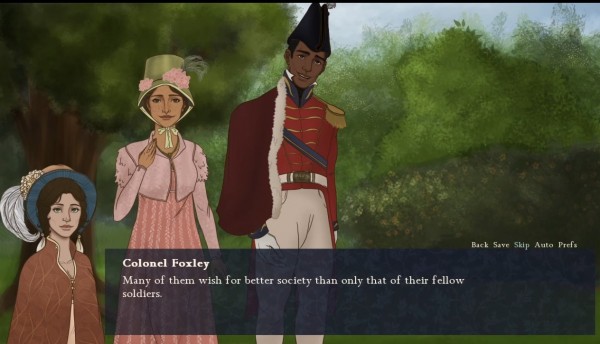

The Lady’s Choice features several characters of color: Arabella’s love interest Colonel Foxley is a Black military officer, with close-cropped hair and a gentle affect. In her review for gaming website Kotaku, Gita Jackson noted that she “gasped audibly in the office” when Foxley was introduced. Under the screenshot of his character, her caption read, “You can’t date him and I’m so upset.”

To date, Foxley is the only unambiguously Black character we have noted in any Austen-inspired game. More common is to give characters a “tan”—which is to say, to make characters racially ambiguous in their coloring, with minimal (if any) other cues as to difference. Arabella is freckled and more tanned than would be expected of a wealthy woman in eighteenth-century Britain. One of the current romantic options, Lord Stanton, has darker skin and dark hair. His sister and nephew also have dark curly hair. It’s not surprising that at least one reviewer, GIRLDANDY, compared Stanton to a “dreamy mishmash of Darcy and Rochester,” given Rochester’s own fraught relationship to nation and race. Mr. Monfort, a secondary character who may be the next plot expansion, is similarly darker skinned.

Screenshot of gameplay from The Lady’s Choice: Arabella and Colonel Foxley

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Maria Walley argues that the game teaches “a lesson for the modern woman: happiness isn’t found by doing what we like, whenever we want.” She identifies the narrow pathway the game created: to simultaneously “navigate society’s rules—while also choosing the right times to break convention in order to follow your heart.” Unlike Austen, The Lady’s Choice can imagine—and depict—happy endings for a heroine not only with a self-made military man but also with the son of a gambler and a prankster who takes on the persona of a Robin Hood-like Society Swindler. Moreover, it also imagines—and depicts, in fan-service-laden detail—a world of expressed desire that in an Austen plot would only end badly.

That tension between expansion and constraint is also present in the way that race is represented. It is certainly more diverse than any other Austen-inspired game currently available, but that diversity is also still largely either ambiguous or relegated to the sidelines of the game’s branching plotlines.

What would “good” representation look like?

By the time that we concluded the first draft of this essay, it was difficult to discuss our analysis of representation in indie Regency games and not immediately think of the debates surrounding the casting choices of the first season of Netflix’s Bridgerton (2020), based on the series by the U.S. Regency romance author Julia Quinn (pen name of Julie Pottinger). The adaptation, created by Chris Van Dusen and produced by Shonda Rhimes, was one of the first shows to emerge from streaming service Netflix’s sizeable deal with Rhimes’s Shondaland production company. Known for producing long-running network television shows such as Grey’s Anatomy (2005–present), Scandal (2011–2018), and How to Get Away with Murder (2014–2020), Rhimes frequently stresses the need for more diversity in front of and behind the camera. Upon winning the 2016 Norman Lear Achievement Award in Television from the Producers Guild of America, Rhimes commented: “It’s not trailblazing to write the world as it actually is. . . . Women are smart and strong. They are not sex toys or damsels in distress. People of color are not sassy or dangerous or wise. And believe me, people of color are never anybody’s sidekick in real life” (qtd. in Garcia). The following year, she reiterated that diverse (which for her includes sexuality and gender, as well as race) and equitable hiring practice should be seen as the norm: “‘My world doesn’t function around making sure that people get included.’ . . . Instead inclusion is a by-product of the fact that ‘there are people of color in my office’ on a consistent basis” (Littleton). Given this background, fans of Rhimes viewed her company’s involvement with Bridgerton as a sign that this period drama would break away from past casting norms where the majority presents as white and where the characters are presumed to be heterosexual as if it were a default.

This promise of at least a more racially diverse cast seemed to be the case as early news of casting and promotional photos began to circulate. Marketed as an inclusive romp, the series reveals the unintended layers of meaning that are added when adapting a textual media to a visual form. Quinn’s vision of the Regency does not include BIPOC characters, but Van Dusen and Rhimes cast Black actors as aristocrats as well as servants and notably add a rationale for the presence of Black aristocracy. Within the world of the show, a yet to be clearly defined racial equity program is implied to have taken place after the marriage of King George III (James Fleet, Scottish-English) to Queen Charlotte (Golda Rosheuvel, Guyanese-British). As we noted earlier, this casting choice fits into a longer historical discussion over Charlotte’s race. It is still debated whether the description of her royal Portuguese forebears as “Moors” suggests Black or Arab African descent. As Ania Loomba points out, in her academic scholarship as well as a recent interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer (Russ), the term is ambiguous, but, in terms of the popular beliefs, Queen Charlotte’s status as woman of mixed European and African heritage has been celebrated by BIPOC British citizens for generations.

In the alternate history of Bridgerton, characters of African descent and high rank refer to Charlotte as “one of their own,” resulting in the elevation of a few to the landed aristocracy. Yet despite the recent integration of the British aristocracy, strangely, characters rarely reference race, colonialism, or slavery, aside from brief exchanges between black-presenting characters Simon Basset, Duke of Hastings (Regé-Jean Page, Zimbabwean-English), and Lady Danbury (Adjoa Andoh, Ghanian-British) as well as between Simon and his father (Richard Pepple, British, presenting as Black). These two conversations center on the precariousness of their new status, that if they are not careful, they will lose all the land, titles, and other markers of status obtained through the royal marriage. Notably, there are multiple BIPOC characters shown in lower ranking positions: modistes, boxers, servants, opera singers, et cetera. The possibility of racism reasserting itself in the show could come through the predication of this attempt at equity on the “happy” royal marriage; out of the public eye, the King’s unpredictable behavior leads to his seclusion and a fraught relationship, with his wife frequently asking servants if he is “dead yet.” It is unclear, at this point, whether the show will use this premise to tackle issues of race, slavery, and empire in any depth.

Bridgerton thus acknowledges historical racism but does not show the larger, systemic implications of that racism. As shown by the material goods that fill each scene, British colonialism appears to still be firmly rooted. Mira Assaf Kafantaris details the way in which “Bridgerton refuses to consider where the sugars and silks of its world come from, while still maintaining a class-based world of servants and poverty” (Kafantaris et al.). Some mothers on the show may fret about the economic consequences of their well-born daughters staying on the marriage market too long, and housekeepers may roll their eyes at the Bridgerton daughters’ ignorance of the labor their servants perform. Yet larger issues of labor remain unanswered. Is the East India Company supplying the muslin needed for the fashionable Empire dress? Does sugar come from the toils of enslaved people in the West Indies? Such silences and erasures, Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall reminds us, come from the nature of corporate studios.

Despite issues of race left largely undiscussed in the series, Bridgerton exists within a larger context of how race has been represented in television, film, and other media. Does, for example, the casting of a Black actor for the role of Simon deploy the trope of the “broken Black family,” as Ambereen Dadabhoy and Kerry Sinanan contend (Kafantaris et al.)? Bridgerton is only the most visible Austen-inspired media creation to struggle with how to get racial representation “right.” As Patricia Matthew notes in an early review of the series, “I don’t really know what ‘right’ looks like for Black characters in an England that in 1813 had abolished the slave trade but not slavery.” There are many ways to get it wrong—some disastrously or violently so.

How to get representation “right” is not simply a problem for major corporate productions such as Bridgerton. Perhaps the most inspiring part of some of the games we discuss, particularly Spiral Atlas’s Northanger Abbey and Seraphinite’s The Lady’s Choice is that they carve out a space for those often excluded in mainstream representations of the Regency. Their subtle commitment to a non-exclusionary approach to race, and in the case of Spiral Atlas, sex along with gender, offers a different representation of Austen’s Regency Britain that is both more historically accurate and, in our current moment, signals the kind of communities we want to build around an era and author to whom we express so much devotion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Em and Emily wish to thank those who provided feedback on this project so far, particularly the audiences at “Jane Austen Days in Philadelphia 2021: Jane Austen in the Modern Age” (JASNA Eastern Pennsylvania) and Virtual JaneCon 2021. Their talk from the latter (and live Q&A) is available on their YouTube Channel, Critical Prof (https://www.youtube.com/c/criticalprof)

NOTES

1There are brief mentions of chinoiserie (i.e., non-Asian imitations of Chinese decorative arts) as well as objects that may be from the Chinese export market or might be European-produced imitations. In Pride and Prejudice, for example, the Bennet sisters suffer through their cousin’s speeches, with “nothing to do but to wish for an instrument, and examine their own indifferent imitations of china on the mantlepiece” (85). More notably, though, Eugenia Zuroski persuasively argues that Austen’s “Northanger Abbey turns the chinoiserie of the English household into a contested site where rationalism and common sense struggle with gothic romance” (256).