Jane Austen’s earliest critics, starting with Sir Walter Scott’s famous unsigned review of Emma in 1815, praised the social and geographical confines of the novel, whose style the Scottish novelist considered reminiscent of the domestic and limited scope of Flemish painting (179). According to Brian Southam, “Of all novelists, Jane Austen is the Anglocentric, narrowly and specifically concerned not with Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, but only with England, the English, and Englishness” (187).1 Her characters are thoroughly English, seemingly unaware of and unconcerned with the changes and tensions within the British Isles, and further afield in the British empire. Claire Lamont notes that Fanny Price’s and Anne Elliot’s cultural curiosity is atypical of Austen’s heroines: “if one asks what most people in Austen’s novels think about the world elsewhere with which their country had such intimate and disturbing relations, the answer is, not much” (308). Austen’s own comments on her artistic practice draw attention to the domestic, provincial focus of her fiction, her claim that “3 or 4 Families in a Country Village is the very thing to work on” implying a deliberate decision to adopt a narrow focus and privilege the local (9–18 September 1814). R. W. Chapman, Austen’s first editor, considered that her “local attachments . . . were no small part of her genius” (47), a view that still dominates the representation of Austen in the popular imagination today. Jane Austen is now “England’s Jane,” who, like her heroine Emma Woodhouse, unquestioningly celebrates “English verdure, English culture, English comfort” (E 391). Emma, however, tests the limits of a narrowly defined Englishness, of local attachments that fail to recognize the value of a diverse community. The novel also interrogates a celebration of Englishness that ignores the uncomfortable realities of British history, thereby complicating a reading of Emma as fundamentally inward-looking.

Written during the Napoleonic wars and published after the final defeat of the scourge of Europe at the Battle of Waterloo, Emma has been read as Austen’s most patriotic novel, a “national tale” with Englishness as its central theme (Southam 190). If Highbury represents a “microcosm of Austen’s world” (McMaster 114), as critics have discussed, Emma is also her most insular novel, its heroine having never travelled much farther than Donwell Abbey, the neighboring estate; it’s not even clear that she has been to London, only sixteen miles away, though her sister lives there. Highbury is a self-sufficient community, whose inhabitants enjoy local produce and believe in the curative powers of their “native air” (E 171). While Mr. Knightley eyes the Gallic Frank Churchill’s movements with suspicions, Mr. Woodhouse urges his daughter to leave off making any more matches, as “‘they are silly things, and break up one’s family circle grievously’” (12), reflecting a concern about changes to a defined social group. Emma seems to share her father’s apprehension: her “‘love of match-making’” (69) is an attempt to preserve the homogeneity of the local community, and by extension England, in contrast to a view of marriage as an important locus of cross-regional and cross-cultural connections and intersectionality. At the same time, Emma yearns for experiences beyond her “confined society in Surry” (156). Frank’s arrival is eagerly anticipated precisely because he offers “the pleasure of looking at some body new” (156). The novel closes on the prospect that Emma will finally go to the seaside on her honeymoon. The threshold between England and the rest of the world, the sea is the point of contact with the other. By contemplating the perspective of the seaside, Emma faces her fear of the unknown other.

Underlining the novel’s focus on the local, characters’ positions in Emma’s world are determined not only by gender and class but also by how long they have resided in Highbury. Emma considers the Eltons “nobody” partly because their money comes from trade, but more importantly because Mr. Elton had “first entered [the neighborhood] not two years ago” (147). Mr. Weston’s connections to trade, on the other hand, as his time away from the village, are overlooked because he is “a native of Highbury” (13). Many villagers have, however, like Mr. Weston and his son, Frank, returned to the community after a period of time “abroad,” which positions them as “insiders-outsiders” (Doody 160), thus complicating the meaning of being native to the place. Emma ignores this fact, but the novel points to an understanding of identity that is more plural and diverse than its heroine allows. Daniel Defoe had already demonstrated in the early eighteenth century that an Englishman is a “Het’rogeneous Thing”:

A True-Born Englishman’s a Contradiction,

In Speech an Irony, in Fact a Fiction. (35)

Austen’s own work has often been read as participating in the creation of such a “fiction,” when it can more properly be seen as expressing scepticism towards it and dramatizing its internal contradictions. As Diego Saglia contends, “Austen’s fiction largely tends to envisage layered and multiple identities, a pluralized Englishness located at the nexus of diverse and competing forms of identification” (76). Emma’s very emphasis on the local presents a nuanced analysis of the “pluralized Englishness” that Defoe had also identified. Austen’s work reveals the difficulties individuals face when approaching these layered identities and accommodating them within an established social group. Because the narrative unfolds within a seemingly homogeneous and harmonious neighborhood, Austen is able to uncover the barely perceptible ways in which differences are erected and discriminations are made within the smallest of communities, reminding us that othering can happen between neighbors.

Austen’s later novels display a particular sensitivity to the almost imperceptible shifts in an individual’s social position that accompany even the faintest of geographical mobilities. In Persuasion, Anne Elliot’s visit to Uppercross provides the lesson that “a removal from one set of people to another, though at a distance of only three miles, will often include a total change of conversation, opinion, and idea” (45). Every social circle, imagined as a “little social commonwealth” (46), is a world of its own, a body politic with its distinct rules, customs, and norms. While the image of the circle conveys the idea of a confined group, the short distance that three miles represent highlights the fact that otherness is not necessarily the result of marked geographical, cultural, or social separations, but can manifest itself within a seemingly defined society, even within one’s family, as Anne experiences when she visits her sister Mary. Once at Uppercross, Anne hopes “to become a not unworthy member of the one she was now transplanted into” (46). No longer in his or her native home, the transplanted individual becomes an other who must undergo a process of assimilation. As Mrs. Elton in Emma surprisingly yet perceptively remarks, “‘one of the evils of matrimony’” is precisely to be “‘transplanted’” (294), which reflects Mr. Woodhouse’s belief that marriage breaks up the family circle and by extension opens up a homogeneous community to external elements. Emma’s “love of match-making” is an attempt to control the entrance of outsiders to her “set” and to preserve the uniformity of her “little social commonwealth.”

Like Persuasion, Emma is attuned to the powerful and alienating function of “the set,” which serves to exclude certain individuals from a group and upholds a social hierarchy. Emma’s amusement at the “picture of another set of beings” (26) that Harriet’s stories of Abbey-Mill farm represent shows the heroine’s abiding sense of the otherness of different “sets.” Alistair Duckworth has noted that “Emma is filled with descriptions of social separations, of ‘first sets’ and ‘second sets,’ of ‘the second rate and third rate,’” a “vocabulary of separation” that serves to marginalize groups within a community (151). The narrative, however, repeatedly refers to the regular visits between “sets,” blurring the neat separation the term establishes. The village encompasses a diverse cross-section of Regency society, which reflects changes within British society more broadly, as the landed gentry elite socializes with professionals such as the Coles and the apothecary Mr. Perry. That Harriet Smith, “the natural daughter of somebody” (22), should be such a central character suggests that even illegitimacy holds less weight in Austen’s world. While the Coles’ dinner party appears as evidence of greater social mobility and diversity, a distinction is nevertheless made between guests, the “less worthy females” arriving later in the evening (231). The Coles thus replicate the very discrimination that they are likely to have experienced in the past, as belonging to the professional “set.” Miss Bates, Jane Fairfax, and Harriet Smith are effectively treated as second-class citizens, whose speaking voices are, moreover, hardly heard during the gathering.

Like these “less worthy females,” the Martin family, who belong to the yeomanry, are never heard, but the novel does not support its heroine’s reluctance to concede the gentility of their characters. Class prejudice animates Emma’s judgment of the family, her social bias leading her to assume that, as a farmer, Robert Martin is “‘illiterate and coarse’” (33), a point she reiterates when she claims that Harriet would be “‘confined to the society of the illiterate and vulgar all [her] life’” were she to marry the young man (56). The Martins are far from illiterate, Harriet having underlined Robert’s habit of reading aloud from Vicesimus Knox’s popular Elegant Extracts (1770) and his eagerness to broaden the range of his reading. Emma is confronted with her own prejudice when she discovers that Robert’s marriage proposal is not only free of grammatical errors, but that “as a composition it would not have disgraced a gentleman” (53). Robert Martin is, for Emma, “‘nothing more’” than a farmer (65), whereas Mr. Knightley considers him “‘an excellent young man’” (63), “‘a respectable, intelligent gentleman-farmer’” with a mind displaying “‘true gentility’” (65, 69). Mr. Knightley separates gentility from rank by connecting it to character, words that are substantiated by his trust in the young man. When he travels to London to deliver some of Mr. Knightley’s papers to his brother John, Robert Martin is first invited to join the Knightley family at Astley’s and to dinner the next day, signaling his inclusion in genteel circles and the novel’s “egalitarian impulse” (Deresiewicz 113). The value of a “set” lies in its diversity and inclusivity, not its insularity.

This egalitarian impulse coincides with a recognition of the social inequalities Britons faced in the early nineteenth century. Although Highbury is a reasonably affluent community, the “poor sick family” (89) Emma visits is evidence that poverty afflicts some of its inhabitants. Living “a little way out of Highbury” (89), the family is geographically removed from the neighborhood, existing only on its periphery, perhaps illustrating the difficulty of confronting poverty. They remain an anonymous and indistinct mass; they are “the poor” or “‘poor creatures’” (93), terms that dehumanize and belittle them. Emma seems to distance herself from the human suffering she witnesses: “it was sickness and poverty together which she came to visit” (93), not a family. Rather than reflecting on the circumstances that have contributed to the family’s hardships, Emma only concentrates on the benefits this visit will have on her: “‘These are the sights, Harriet, to do one good’” (93), a comment that underlines the self-interest of her charitable action. The visit is a sort of comforting blanket that reminds Emma of her privilege but does not lead to further examination; the “poor creatures” are soon forgotten and never visited again, remaining firmly on the margins of the community. Emma is seemingly unconcerned by the extreme poverty that afflicted most of the British population.2 Poverty, however, resurfaces towards the close of the novel, when Mrs. Weston’s poultry-house is robbed, “evidently by the ingenuity of man” (528), a reminder that the novel does not forget the presence of economic hardships in England as swiftly as its heroine does.

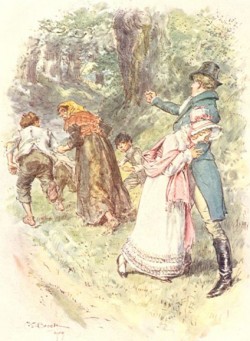

The “gypsies” Harriet encounters with her friend Miss Bickerton are often named as the likely culprits. They also live on the outskirts of the village, at first glance signaling their marginal status. In his reading of the episode, Michael Kramp has argued that the gypsies are marked as racially other, the opposition between “the ‘Black’ migratory gypsies” and “the White residents of Highbury” helping to establish a defined “English race” (150). Sarah Houghton-Walker has, on the other hand, recently demonstrated that, despite their traveler status, “Austen’s gypsies, far from representing difference, represent an aspect of Englishness: they are an integral part of the fabric of the rural community” (184).3 As such, the natural presence of the gypsies mirrors the diversity of the local population. While a source of anxiety for many of the characters, their position in the novel is not as sinister as one might expect. The incident takes place on the Richmond road, “[a]bout half a mile beyond Highbury” (360), marking the world outside of Highbury as a dangerous place, potentially populated by a malignant other. When Frank, having patriotically rescued Harriet, guides her back to Hartfield, the young woman knows she is safe when the “iron gates and the front door” are less than twenty yards away (360). The iron gates represent the boundary between Hartfield and the outside world; they are the material sign of the Woodhouses’ fear of the other and need to protect themselves from alien intrusions.

The “gypsies” Harriet encounters with her friend Miss Bickerton are often named as the likely culprits. They also live on the outskirts of the village, at first glance signaling their marginal status. In his reading of the episode, Michael Kramp has argued that the gypsies are marked as racially other, the opposition between “the ‘Black’ migratory gypsies” and “the White residents of Highbury” helping to establish a defined “English race” (150). Sarah Houghton-Walker has, on the other hand, recently demonstrated that, despite their traveler status, “Austen’s gypsies, far from representing difference, represent an aspect of Englishness: they are an integral part of the fabric of the rural community” (184).3 As such, the natural presence of the gypsies mirrors the diversity of the local population. While a source of anxiety for many of the characters, their position in the novel is not as sinister as one might expect. The incident takes place on the Richmond road, “[a]bout half a mile beyond Highbury” (360), marking the world outside of Highbury as a dangerous place, potentially populated by a malignant other. When Frank, having patriotically rescued Harriet, guides her back to Hartfield, the young woman knows she is safe when the “iron gates and the front door” are less than twenty yards away (360). The iron gates represent the boundary between Hartfield and the outside world; they are the material sign of the Woodhouses’ fear of the other and need to protect themselves from alien intrusions.

This fear of the other appears most strikingly in Emma’s “love of match-making,” the expression of her desire to preserve her “set” from social fragmentation, which the novel suggests is already undermined by Britain’s inherent plurality. As Douglas Murray observes, “Emma is a woman with a compulsive rage for order and, in a semiotic sense, purity” (956). For Emma, “true gentility” is “untainted in blood and understanding” (E 389). While references to “blood” and “tainting” are obvious allusions to social standing and sexual promiscuity, another important element is their connection to race. Kramp argues that Emma’s and Mr. Knightley’s interest in Harriet is only as “a potential biological and cultural reproducer of England’s ‘race’” (148). Harriet, “short, plump and fair, with a fine bloom, blue eyes, light hair, regular features, and a look of great sweetness” (E 22), “appears as the anonymous and archetypal Anglo-Saxon female, complete with the traditional physical qualities of the ostensibly ancient race of England” (Kramp 150–51). When Harriet’s parentage is revealed, her gentility rises no higher than the trading classes, “likely to be as untainted, perhaps, as the blood of many a gentleman” (E 526). This ironic aside reminds the reader that any English gentleman’s blood is likely to be as tainted as that of his social inferiors, dismantling efforts to preserve the homogeneity of a “set.”

The novel, moreover, constantly points towards a world outside of the confined society of Highbury, illustrating the idea that the English are a “Het’rogeneous” people. The impress of the outside world is best exemplified in Jane Fairfax’s personal history. Though a native of Highbury, Jane is supported by connections between the British Isles, which tie her to British military ventures overseas. Her father, Lieutenant Fairfax, died “in action abroad” (174), presumably in the Napoleonic wars. Jane’s history is deeply connected to Britain’s military forces as she is raised by Colonel Campbell, whom her father nursed “during a severe camp-fever” (174). The Scottish name “Campbell” exemplifies the role that the army and the navy played in forging a sense of British (rather than merely English) national identity.4 It is thanks to the Campbells that Jane acquires the education and skills required to take on a position as governess, indicating mutual support between British subjects. The trajectory of Jane’s friend Miss Campbell is similarly a very British story: she meets the Anglo-Irish landlord Mr. Dixon in Weymouth, a resort in Dorset on the south coast of England. The newlyweds travel to Mr. Dixon’s seat of Ballycraig from the Welsh port of Holyhead, the principal ferry town to Ireland. These different locations reflect the interconnectedness of British and Irish regions, illustrating Deidre Lynch’s claim that “Austen eschews a cut-and-dry opposition between the local and the long-distance” in Emma. In her persuasive reading of the Box Hill episode, Lynch further argues that Emma’s anticipation of the rumors concerning her flirtation with Frank Churchill that will be sent to Maple Grove and Ireland “bring[s] us up against the limits of England and Englishness,” as it acknowledges the existence of social circles beyond the narrow compass of Highbury. These imbedded interconnections also trouble the neat opposition between us and them, and periphery and center, that the identification of “sets” implies.

Rather than willfully ignoring the nations that surround England, Emma dramatizes the difficulty of accounting for the plurality that Britishness entails and argues for a greater degree of inclusivity. The only clear reference to the Act of Union of 1801, which established the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, is found in Miss Bates’s remark that Mrs. Dixon and her parents are now “‘in different kingdoms, I was going to say, but however in different countries’” (170), the self-correction a sign of how recent this change is. Fiona Stafford notes that Miss Bates’s “sense of the abiding otherness of Ireland” neatly captures the pace of individual perceptions of nationhood (97), which evolve more slowly than political changes. Ireland is more familiar to Highbury than Miss Bates’s mistake might otherwise suggest, as Irish culture infiltrates the community’s drawing rooms with Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodies (1808–1848), which also encode Irish politics (Donovan 16–17). Julie Donovan argues that Frank’s instrumentalization of Ireland as a decoy for his relationship with Jane recalls the British manipulation of the Union at the expense of Ireland (18–19), indicating the novel’s sensitivity to Ireland’s continued oppression. If, as Donovan observes, “Ireland’s marginality in Emma is deceptive” (13), Scotland is also represented as an important contributor to England’s prosperity, when John Knightley’s friend Mr. Graham, himself of Scottish descent, hires a Scottish bailiff. Emma wonders if “‘the old prejudice’” against the Scotsman will not be “‘too strong’” (111); the novel again registers tensions between England and the Celtic nations and the challenges to the establishment of a shared sense of Britishness, where diversity is synonymous with tolerance.

An important point of British history that Emma addresses, which reaches beyond the boundaries of Highbury, is the question of slavery. “Reading Austen postcolonially,” as Rajeswari Sunder Rajan points out, “is an inescapable historical imperative in our times” (3). Following the work of Edward Said in particular, we can no longer assert with the same confidence as D. W. Harding that Austen “presents quite naturally and effortlessly the general revulsion of feeling against slavery and the careful trimming of their sails to this new wind by people whose money, coming from Bristol, might be suspect” (50). In her eagerness to assure her interlocutors that “‘Mr. Suckling was always rather a friend to the abolition’” (E 325), Mrs. Elton underlines the fact that no discussion of slavery is effortless. The introduction of the clergyman’s wife first alludes to Britain’s connection to the slave trade through her native home:

Miss Hawkins was the youngest of the two daughters of a Bristol—merchant, of course, he must be called; but, as the whole of the profits of his mercantile life appeared so moderate, it was not unfair to guess the dignity of his line of trade had been very moderate also. (196)

As Mary DeForest has shown, Mrs. Elton’s maiden name itself connects her to the slave trade (11), the “moderate dignity” of this “line of trade” a further hint at this connection.5 While the dash certainly reflects Emma’s class prejudice and contempt for those in trade, opting for the more distinguished “merchant” over the inferior designation of “shopkeeper” or “tradesman” (E 566n2), it is vital that we discuss the Hawkins family’s and Bristol’s connections to the slave trade, as Gillian Ballinger has recently explored. While the dash can be read as the sign of a discomfort and reluctance to face Britain’s reliance on the transatlantic slave trade, it introduces a pause that calls attention to itself, demanding that readers think about the meaning of this location.

The silence that the dash introduces is a metonymy for the unspeakable horror of slavery, which cannot be ignored. Jon Mee argues that slavery is “a virtual presence” in Austen’s novels (90), but the entrance of Mrs. Elton and her native home of Bristol into the narrative world asks that we remember that the history of slavery is intertwined with British local history, troubling the heroine’s confidence in “English comfort.” As the website and database Runaway Slaves in Britain points out, “Thousands of people of African, Asian and Indigenous American descent” worked as domestic servants in British homes: “Some were free, others were bound and indentured servants, and some were enslaved.” Slavery was therefore on Britons’ doorsteps. The very people who protected the nation and helped defeat Napoleon could also be involved in the slave trade. Admiral Nelson, for instance, counted many friends who were slaveholders and was opposed to William Wilberforce’s abolitionist campaign.6 Furthermore, the Act of 1807 abolished the slave trade only; it was not until 1833 that slavery itself was abolished in most British colonies. Yet the abolition movement remains an important part of British history, and print culture was instrumental in popularizing its ideas. Many critics have persuasively demonstrated that Austen’s fiction engages with abolitionist discourse in sophisticated ways, weaving in the connections of everyday objects to slavery, such as Lady Bertram’s sofa (Stafford 73–74), which lie beneath the smooth surface of Austen’s “little bit . . . of Ivory” (16–17 December 1816).7 Emma’s silence offers such an instance, inviting us as readers and teachers of Austen to address the local signs that the British empire was partly built on slavery.

The parochial nature of Emma is undeniable. Yet its local focus should not be equated with escapism. The novel’s nuanced examination of the othering function of the “set” exposes the subtle acts of discrimination within a seemingly homogeneous community, whose uniformity is, in fact, a fiction. The novel also displays a British, rather than narrowly English, focus, underlining the diversity that characterises Britishness, while remaining alert to the tensions within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the enduring prejudices against the Celtic nations. Rather than eschewing the darker realities of Britain’s international presence and colonial exploitation, in particular its connection to slavery, Emma’s local focus serves to illustrate the domestic realities of the slave trade. As recent events in Bristol and elsewhere have shown, Britain’s slavery and colonial past must be acknowledged.8 Rather than silencing those issues, Austen’s fiction allows for important conversations about British history to take place.

NOTES

1Critics have noted that this narrow English focus is found in the published fiction. Ireland, Scotland, and Wales feature prominently in the juvenilia. See, for instance, Southam.

2See, for instance, the recent study by Ian Mortimer.

3Laura Mooneyham White has also explored this episode in detail.

4For a classic study, see Linda Colley.

5Gillian Ballinger also makes this point.

6For an illuminating discussion of the British Navy and the slave trade, see McAleer and Petley.

7Gabrielle White offers the most extensive study on this subject.

8On 7 June 2020, Black Lives Matter protesters in Bristol toppled the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston in an effort to shed light on his controversial legacy.