The Lefroys of Ashe and the Austens of Steventon, Hampshire, were close friends as well as colleagues in adjoining parishes. From the arrival of the Lefroys at Ashe in the early 1780s, the families attended assemblies and exchanged visits. Jane Austen’s brother the Reverend James Austen was the last friend to see Anne Lefroy alive before her death after a fall from a horse in December 1804. The ties between the two clans remained strong into the next generation: the youngest Lefroy son, Ben, was in 1814 to marry James’s daughter Anna Austen. This essay will examine the life and work of Ben’s older brother, Christopher Edward (1785–1856, known as Edward), with a particular focus on his brilliant, forgotten, anti-slavery novel, Outalissi: A Tale of Dutch Guiana (1826). Lefroy and his novel embody and express an intersection between the circles of standard village Anglicanism and the abolitionist Evangelical wing, with its global focus and uncompromising campaign against race-based oppression. In keeping with the theme of this special issue of Persuasions On-Line, Outalissi takes us far “beyond the bit of ivory” into the fusion of diverse cultural and human communities that was colonial Surinam. This essay can, however, only offer a prologue to the study of an important work (of which a fresh scholarly edition would be welcome) from the radical periphery of the Evangelical movement.1

The Lefroys of Ashe and the Austens of Steventon, Hampshire, were close friends as well as colleagues in adjoining parishes. From the arrival of the Lefroys at Ashe in the early 1780s, the families attended assemblies and exchanged visits. Jane Austen’s brother the Reverend James Austen was the last friend to see Anne Lefroy alive before her death after a fall from a horse in December 1804. The ties between the two clans remained strong into the next generation: the youngest Lefroy son, Ben, was in 1814 to marry James’s daughter Anna Austen. This essay will examine the life and work of Ben’s older brother, Christopher Edward (1785–1856, known as Edward), with a particular focus on his brilliant, forgotten, anti-slavery novel, Outalissi: A Tale of Dutch Guiana (1826). Lefroy and his novel embody and express an intersection between the circles of standard village Anglicanism and the abolitionist Evangelical wing, with its global focus and uncompromising campaign against race-based oppression. In keeping with the theme of this special issue of Persuasions On-Line, Outalissi takes us far “beyond the bit of ivory” into the fusion of diverse cultural and human communities that was colonial Surinam. This essay can, however, only offer a prologue to the study of an important work (of which a fresh scholarly edition would be welcome) from the radical periphery of the Evangelical movement.1

In the fall of 1816, in what would turn out to have been the final months of Jane Austen’s life, the Austen women received a visit at Chawton from Edward, newly trained in the law, and Ben, shortly to follow eldest brother John Henry George in taking holy orders. Jane Austen recorded, approvingly:

[Christopher] Edward & Ben called here on Thursday. Edward was in his way to Selborne. We found him very agreable. He is come back from France, thinking of the French as one cd wish, disappointed in every thing. (8–9 September 1816)

Jane Austen was as perceptive here as ever. As a teenager, Edward had worked in a lawyer’s office in Newport, Isle of Wight. From his mother’s letters, we learn that he had evidently expressed a desire to join the British army during the period of 1803–1804, when a French invasion seemed imminent. The Reverend George and Anne Lefroy were strongly opposed to such a career (H. Lefroy and Turner 168–69). Shortly before the death of his father (the Reverend George Lefroy succumbed to a stroke in January 1806), Edward fell out with his employer, the lawyer Mr. Clarke, got into debt, and became engaged to a Miss Winter. The Winters were Dissenters, a sensitive issue among the strongly Anglican Lefroys (Stove 200). In the event, the engagement was abandoned, and Edward was never to marry. Following his B.A. in 1815 and M.A. in 1816, Edward was called to the bar in 1819 (H. Lefroy and Turner 17).

Shortly after, Lefroy took on the post of British Commissary Judge of the Mixed Court in Surinam, established by a treaty with the government of the Netherlands for the suppression of the slave trade. On the northeastern coast of South America, Surinam was a plantation colony, its principal exports coffee and sugar. After the defeat of Napoleon and the ensuing Treaty of Paris (November 1815), Surinam was restored to the new Dutch monarch, Willem I. The Treaty of Paris reinforced the provisions of the Congress of Vienna regarding slavery, stating that the signatory governments should move towards the abolition of the trade (Additional Article 292). The new Dutch government made slave trading illegal for Dutch subjects and in theory supported the English ban. Yet even in British colonies slavery was still practiced, as it would be until the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. The result, in the Surinam of the 1820s, was a mix of official blind eyes, corruption in various forms, and the inevitable, persistent arrival of slave ships. Lefroy wrote an incendiary novel about his experiences, published anonymously in London in 1826: Outalissi: A Tale of Dutch Guiana.

It turned out that Lefroy, so long frustrated by his parents and his brother in every direction that he sought—whether his desire to join the army or to marry—was a writer of considerable gifts. Outalissi is an impressively structured work that analyzes the moral aspects of slavery and race relations, featuring a hero of color, Outalissi, in parallel to its white hero, Edward Bentinck, Lefroy himself very lightly disguised. It is also a shocking book, featuring the rape and murder of a teenaged enslaved girl, Charlotte Venture, and the violent torture and execution of a blameless missionary as well as of Outalissi. Dutch and English, European and African cultures are contrasted and intertwined. The story grips the reader despite its frequent philosophical and religious digressions. Lefroy’s own experiences lend authenticity to the scenes, and occasional flashes of humor leaven the tragic events.

Ostensibly part of a wave of Evangelical novels in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Lefroy’s book in fact subverts aspects of the genre. Most of the books in this tradition were written by and often for women, reinforcing tropes relating to virtuous behavior (Mandal 259). The cultural mood was one of reaction against French revolutionary upheaval and its origins in the writings of the philosophes, at least as perceived through a British conservative lens. Closer to home, there was a revulsion against the lifestyle represented conspicuously by clergy such as the Reverend James Austen, whose occupation of plural livings delegated to lower-paid curates reflected the relaxed Anglicanism of the old century (Mandal 258). (“Plurality” was to be outlawed by the Pluralities Act 1838 [Cross].) While largely sharing this mood of Evangelical reaction, Lefroy shows clear influence from the most trenchant of the philosophes, Voltaire himself, in his coruscation of colonial practices.

The plot consists of a few key events. Edward Bentinck, an officer in the Dutch army, falls in love with Matilda Cotton, whose father owns a slave-worked plantation. Mr. Cotton holds religion in contempt and British law in defiance, knowing that there will be no official inclination to investigate apparent instances of slave trading. An English sailor confides in Bentinck that he has witnessed a slave ship, with a French captain, arrive. Bentinck passes this information to the British and Dutch authorities, thus betraying his beloved’s father. One of the group of slaves, Outalissi, manages to escape. The action of the novel climaxes in a slave rebellion led by Outalissi, resulting in the destruction by fire of much of the capital, Paramaribo (an event which actually occurred in January 1821). In Lefroy’s treatment, this fire is presented as a just retribution for the burning of Outalissi’s home village at the time of his capture in Africa.

Previous literary treatments of Surinam as paradigmatic slave state are significant. Aphra Behn probably spent time during the 1660s as a young woman in Surinam (at the time a British possession), and her Oroonoko (1688) was set in the colony, featuring an enslaved African prince as the hero (Todd). Voltaire’s Candide (1759) represents another significant intertext for Outalissi. Candide and his native American friend Cacambo visit Surinam, coming upon an African slave lying on the ground, mutilated as a punishment by Dutch traders (75). This man had received no comfort from the Dutch clergy. These are themes which Lefroy would develop in his work. Bentinck hears about the hypocrisy of Christians from a Surinamese Indian, the old man Pannana: “No, massa, we are convinced that the Christians are more depraved in morals than we Indians, if we may judge of their doctrines by the general badness of their lives” (138).

The name “Outalissi” already had a history as attaching to a new-world hero. Thomas Campbell’s 1809 epic poem, “Gertrude of Wyoming,” had featured an Oneida hero by that name. Campbell himself had borrowed the name from Chateaubriand’s “Atala” (1801), in which the father of an American chieftain, Chactas, has the name Outalissi (Bierstadt 494). Campbell’s Outalissi had demonstrated his unselfishness in saving the life of a white child, as does Lefroy’s Outalissi (Matilda’s little brother, Charles Cotton). Campbell’s poetical works form another intertext, with Lefroy quoting from his verse in the epigraphs to several chapters of the novel.

Lefroy’s Outalissi is depicted quasi-visually. His impressive physique is likened to the Apollo Belvedere, considered since the writings of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) as the ideal of Western male beauty. This classicizing tendency was an attempt to familiarize the unfamiliar, to assimilate the lesser known individual to the better known (European) culture; active scholarly debate persists around the extent to which neoclassical aesthetics in the period represented racist prejudice (Hodne 9). In Lefroy’s treatment, the intention is undoubtedly positive. Recalling a classical god or hero from Greek myth, Outalissi’s perception and strength in the novel seem supernaturally charged (as when he appears, seemingly from nowhere, to rescue Matilda from the Paramaribo fire). Again perhaps echoing Winckelmann, Lefroy seems to suggest that human greatness should be associated with freedom, in contrast to Outalissi’s condition of enslavement (Hodne 10, 16).

I need not remind such of my readers as are familiar with the models of ancient sculpture, that the expression of figure is often quite as definite as that of feature. . . . There was no stoop in [Outalissi’s] shoulders, his stature was perfectly erect, his knees and ancles and all his limbs were beautifully clean and elastic, his muscles had evidently none of them been unequally strained, his whole appearance, in short, denoted a man who had never had any other master than his own will. (35–36)

The irony is that in formal terms Outalissi is subject in all his actions to white masters.

Lefroy also attributes the classic Western virtues of self-control and courage to his black hero in facing trial, torture, and execution.

Nothing could be more imposing than the appearance of Outalissi, his figure was quite equal to that of the Apollo Belvedere. . . . Outalissi’s composure arose evidently not from the absence of passion, but the intenseness of self-controul—exultation, disdain, and conscious self-sufficiency, and fortitude of nerve to conceal every emotion of weakness that could give the slightest triumph to his Christian judges, under any tortures which they might inflict. (223–24)

The two other classic Greek virtues were wisdom and justice, the latter clearly missing from colonial administrative process, a fact underlined by Lefroy in an appendix stating the questionable legality of such proceedings (317–18nT). Outalissi goes to his death by firing squad, comforting little Charles Cotton with the prospect of meeting again.

Outalissi’s execution follows upon the kangaroo-court trial, torture, and execution of Mr. Schwartz, the Moravian missionary, for having allegedly encouraged the slaves to become Christians and therefore to hold their masters in contempt. A relevant event is clear from Lefroy’s references in both text and footnotes: the 1824 death of young missionary John Smith (1792?–1824), following a slave uprising in the neighboring British colony of Demerara (now part of Guyana). The events around Smith’s life and death had only lately demonstrated that in important ways, the administration of a British colony was not superior, morally or legally, to that of the Dutch.

In August 1823, a revolt was planned and carried out by about ten thousand slaves on the Demerara plantations. John Smith refused to take up arms against the slaves; he had converted many to Christianity, encouraged them to attend services, and helped them learn to read. The revolt was put down with brutality, and Smith, after a trial by court-martial, was sentenced to death. As information about the revolt and its aftermath filtered through in Britain, the home government decided to commute the sentence in response to public outrage. Unfortunately, Smith died of illness in prison in February 1824, before receiving news of the change (Carlyle and Heuman).

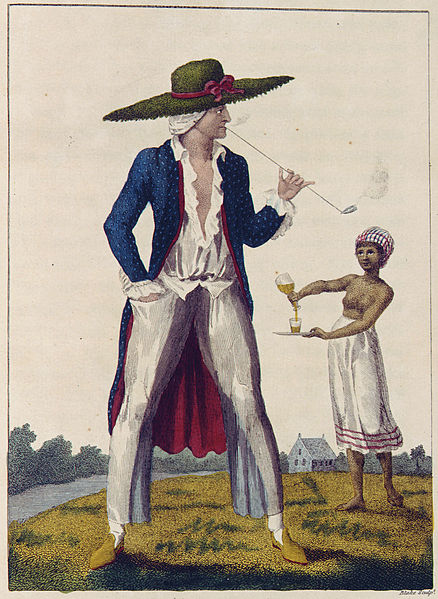

A further important intertext with Outalissi was the combination of the scandalous life and the openly sexual writings of John Gabriel Stedman (1744–1797), Dutch-English soldier and adventurer. Lefroy refers to Stedman’s notorious Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796). In another subversion of the Evangelical text, Lefroy, like Stedman, tackled head-on the sexual exploitation of slaves. Stedman had played the parts of both moral witness, exposing the hideous cruelty characterizing slave life in Surinam—William Blake’s unforgettable illustrations lending visual impact to what has been aptly called Stedman’s “humanitarian pornography” (Klarer)—and sexual exploiter, in all probability, of enslaved women and girls (Price). For his part, Lefroy seeks to illustrate the intersections of power and sex in three contexts. The first is an attempt to corrupt Bentinck, by means of an enslaved Surinamese woman sent, naked, to his room late at night. Bentinck himself is clothed only in a cloak and a grass necklace earlier purloined from Matilda, a talisman which offers moral prophylaxis: “Certain it is that surrounded, as he was, by every temptation as well as facility of indulgence, nothing but such a spell upon his heart, or religious impressions of more than human strength, could have preserved him in that point of conduct, from irretrievable moral ruin” (116).

|

|

|

| Engravings by William Blake, from John Gabriel Stedman's Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796). | ||

The second of Lefroy’s approaches concerns the treatment of enslaved woman Charlotte Venture. Charlotte has become a Christian through the influence of Mr. Schwartz and grown attached to Outalissi. The brutal manager of Mr. Cotton’s estate, Mr. Hogshead, violently rapes Charlotte and leaves her for dead, in the near certainty of facing no legal penalty (178–79). Lefroy clearly portrays the way in which sex was used as an instrument of power and oppression against the female enslaved, here too echoing Stedman and William Wilberforce himself, who had publicized the treatment of female slaves on Caribbean plantations (Klarer 562–64).

The final way that Lefroy addresses the politics of sexuality is to point out that as slaves were not permitted to marry, all that was left to them was extra-marital intercourse, a mortal sin under Christianity. The slaves complain to Outalissi as their leader: “Every obstacle is interposed to our marrying, and the rite of baptism is generally denied to our children. . . . [O]ur wives and daughters [are subjected to] worse than murder—to satiate the lusts of every brutal manager whom they choose to appoint over us” (182).

The denouement of the novel’s plot sees the union of Bentinck and Matilda, at the bedside of her dying father. Mr. Cotton converts to Christianity through the witness of his virtuous Christian daughter, and the eloquent apologetics of an English minister, Mr. Austin. This naming was surely a nod to the family friends from Hampshire: as late as 1833, the name of Jane Austen’s brother, by then Vice-Admiral Sir Francis, appeared in print with the spelling “Austin” (Prosser vii). Lefroy was evidently attempting, in the lengthy arguments given to Austin, to overcome his own doubts about the problem of evil and the role of Christianity in the developing world. Earlier in his youth, Lefroy had begun to experience religious doubt. He had written to his brother, the Reverend J. H. G. Lefroy, with arguments about doctrine. His brother’s response was tactful, but tended to close off discussion:

I am most sensible my dear Fellow of the Christian benevolence & affection which dictate your Letters to me on the subject of Religion. At present I can only say that it is my earnest wish & fixed intention to endeavor both to fashion my own life & to feed my flock according to the doctrine of Christ & that upon his mercy only I depend for knowledge & strength for that purpose. (14 January 1808, Stove 207–08)

Not for a busy young working clergyman the leisure to examine the foundations of belief.

Edward continued to meditate on the version of Anglicanism which he had inherited from his parents and his class, and to find it wanting. In the novel, he has Bentinck consider:

He thought also, that the majority of [Anglican] clergy were men of unimpeachable moral integrity, and some of “the salt of the earth,” but there was something in their mode of discharging their duties, a shyness of the subject of religion in conversation, and a timid caution of the slightest deviation from prescribed formulæ, that always conveyed to his mind a doubt of their own confidence in the doctrines of which they were the appointed communicators to the public. (244)

In achieving London publication with the house of John Hatchard—associated with Wilberforce and other writers of an Evangelical tendency (Sydney 244)—Lefroy may have hoped for literary success, which eluded him.

Describing the novel in his mid-nineteenth-century family history, Lefroy’s nephew, Sir John Henry Lefroy (1817–1890), acknowledged its strengths, but deplored its negative effect on its author’s career.

It is very readable, full of simple but vivid sketches of tropical life and nature, of the insight of a clever high-principled man, of no particular powers of imagination, into human life and character, and of the deeper thoughts of one profoundly religious, but led by his turn of mind and solitary life into those intellectual difficulties from which our present light offers no escape. It would of course be pronounced prosy by a reader of novels, on the other hand the vices he pourtrays, and the cruelties he describes, lead him into one or two descriptions which would not be admitted into the columns of a periodical of the present day. Its publication had a very disastrous effect on the writer’s fortunes, for the [Surinam] planters chose to view it as a libel, and made such representations to the Colonial Office as led to their mulcting him in 1829, of £150 a year retiring pension, an act which he always contended to have been purely illegal. (J. H. Lefroy 113n).

Outalissi and its anonymous author, then, had already passed into obscurity, even within the extended Lefroy clan who were to be the readers of Sir John’s work.

Returning to England on the death of his brother Ben, aged only thirty-eight, in 1829, Lefroy purchased a property near Basingstoke for the widowed Anna and her seven children, his nieces and nephews (Lefroy and Turner 18). We may wonder what Jane Austen would have made of the sex, the violence, and the activism of Outalissi: she did not like the Evangelical style in literature, as she wrote to Cassandra in 1809 (24 January). Yet some years later, called on to advise her cherished Fanny Knight on a prospective suitor, she freely acknowledged the movement’s moral credentials: “I am by no means convinced that we ought not all to be Evangelicals, & am at least persuaded that they who are so from Reason & Feeling, must be happiest & safest” (18–20 November 1814). Jane Austen would surely have been personally grateful to the author of Outalissi, had she lived to see another beloved niece Anna and her children supported after their bereavement.

Like his father, Edward suffered a stroke, in 1852, and did not recover from partial paralysis prior to his death in 1856 (J. H. Lefroy 166). He must have rejoiced when slavery was finally ended in British colonies in 1833. As it was not terminated in the Dutch colonies of the Caribbean until the 1860s (Allofs et al. 316), Lefroy never knew the outcome for which he had so passionately argued in his book.

Only in 1975 did Surinam finally transition to independence from the Netherlands (Krus 345). The cultures of African groups whose members were transported to Surinam during the colonial period have been the subject of research in recent decades, with a view to exploring the survivals of African cultures in the new world. While scholars differ on the extent of survivals as opposed to syntheses, research into cult practices on the plantations has tended to support the picture drawn by Lefroy of certain religious or belief systems as being maintained among the enslaved workforce (Krus 320). Researchers have also established the existence of special relationships between the slaves incarcerated on the same ship, confirming Lefroy’s emphasis on the importance of the solidarity created by enslavement, such that Outalissi refuses to reveal other rebel names (224; Krus 321).

Some survivals can be seen in language. Sranan Tongo, a Surinamese-Dutch-English fusion first recorded in the eighteenth century among European settlers, enslaved Africans, and native Americans, is still spoken by some 300,000 people in Surinam, preserving African language elements (Krus 334). It thus serves as a living testimony to the clash and blending of histories and cultures—African, Dutch, English, native Amerindian—which Lefroy entered in 1819 and which he later chronicled powerfully in his extraordinary novel, Outalissi.

NOTES

1A short version of this essay was presented at the panel “Romanticism, People of Color, and 1819” at the International Conference on Romanticism, Manchester, U.K., July 31–August 2, 2019. Thanks are due to the panel members. The author has made initial inquiries regarding the copyright status of Outalissi (of which a facsimile is currently available through Gale Nineteenth Century Collections Online, among other online sources), with a view to undertaking a projected new edition, but has not yet found a publisher to undertake the project.