For three years in the 1970s I lived within four miles northward of Exeter in a village on a hill overlooking the River Exe. At that time, literature degree courses focused exclusively on text, and I did not think while studying Sense and Sensibility to investigate the geographical connection between this location and the Dashwoods’ Barton, still less to map the novel’s physical and mental landscapes. That contextual interest developed later, in the flat expanse of East Anglia, where I failed to settle amid the wide horizons and open vistas. Maps of the West Country and Jane Austen’s novels, particularly Sense and Sensibility and Persuasion, formed my chief consolations until I could return to live within four miles northwest of my previous home. In the late eighteenth century my tiny thatched farm laborer’s cottage, within walking distance of three of the many bartons in this part of the county, would not have looked as pristine as it does today, but the muddy lane leading to it along the bottom of the valley would be familiar. The road from the nearest town, Crediton, into Exeter, the ancient capital city of Devon, follows the same route as it did in Jane Austen’s day, passing Sense and Sensibility locations on the way and crossing the River Exe at Cowley Bridge.

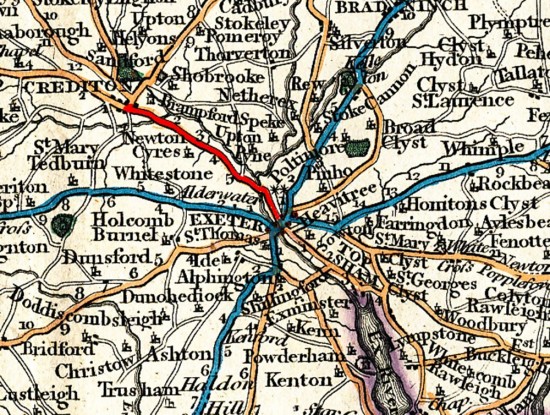

Enlarged extract from Cary’s New and Correct English Atlas (1821) showing the road from Crediton and the area “four miles northward of Exeter.”

This area of Devon is and was off the main tourist trail to the seaside resorts and as such was only familiar to the local inhabitants—farmers, laborers, clergy families, and landowners. A few visitors, including William Gilpin, came in search of scenery worthy of being translated into art, and left disappointed, but the Reverend John Swete, who owned property south of Exeter and applied less stringent rules to his interpretation of picturesque principles, found more to inspire his pen and paintbrush. Of the countryside to the north and west of Exeter he noted that blend of beauty and utility admired by Edward Ferrars: “it would not be very easy to point out a track of Country, in admiration of whose prospect, the Landschape Painter and the Farmer would sooner coincide” (Gray 127), he wrote in the summer of 1797.

As is usual in Jane Austen’s novels, with the exception of Persuasion, detailed descriptions of landscape are neatly sidestepped. Of Devonshire, the reader learns that there are hills and valleys, open downs and cultivated fields, woods and pastures, fine views and dirty roads, aspects of landscape common to many counties of England. Yet the location of Barton, “within four miles northward of Exeter” (SS 29), is more specific than the fictional locations in the other five novels, and the physical landscape is used to greater effect in revealing mental landscapes, foreshadowing concealments, and eventually facilitating openness and healing.

![]()

In the 1790s, when she began writing the first draft of Sense and Sensibility, Jane Austen had no personal experience of this southwestern county, with its 450 miles of coastline, developing seaside resorts, and two great areas of moorland. The South Devon Militia, recruited in the neighborhood of Exeter, was quartered in North Hampshire over the winters of 1793–1794 and 1794–1795, and it is likely that Jane danced with the officers at the Basingstoke Assemblies and heard a little about their home territory. Another source of information in the early 1790s was surely Richard Buller, one of the pupils at Steventon Rectory and the Bishop of Exeter’s son. On her father’s shelves was a copy of William Tunnicliffe’s Topographical Survey of the Counties of Hants, Wilts, Dorset, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, published in 1791. The Reverend George Austen’s name appears in the list of subscribers, so the book was immediately to hand. Its fold-out maps and detailed descriptions of topographical features would have made Jane Austen a tolerable proficient in the geography four miles northward of Exeter.

By the time she came to revise the manuscript of Elinor and Marianne at Chawton, she had, in the early 1800s, visited Teignmouth, Dawlish, and probably Sidmouth. The sea makes no significant appearance in Sense and Sensibility, although Dawlish is mentioned, and the Dashwoods’ household possessions are transported from Sussex by sea, along the south coast of England, then up the River Exe and the new canal to the busy quay at Exeter. Sir John Middleton’s summer parties on the water happen inland, presumably on rivers and private lakes, and not even Marianne voices a longing for craggy coastal scenery. Maybe Jane Austen considered Marianne’s passion for Willoughby dangerous enough without making her wild for the sea as well. Robert Ferrars alone appears to consider the coast as a destination, and then only Dawlish, which also happens to be Lucy Steele’s hometown. Although a fashionable spot, with smart lodging houses and a strand along which to promenade, the library there was, in Jane Austen’s opinion, “particularly pitiful & wretched” (10–18 August 1814), which makes it the ideal place for these two shallow characters to exhibit themselves.

In contrast, the latest BBC production of Sense and Sensibility (2008) recognized the potential of seascape rather than landscape in depicting the dramatic ebb and flow of the heroines’ turbulent romantic attachments. The choice of location for Barton Cottage, on the cliffs above, is not four but forty miles northward of Exeter, on the quite distinct—and distinctly wrong—North Devon coast.

Robert Ferrars’s comments on cottages in the final version of the novel might owe something to Jane Austen’s own visit to Dawlish in 1802. It is hard to imagine his lengthy pronouncement on the luxuries of cottage drawing rooms, dining rooms, libraries, and spaces for eighteen couple to dance, reproduced in a letter from one sister to the other. I suspect it was added in a later revision, when Jane Austen might have seen at Exminster, on the road between Exeter and Dawlish, Mr. Lardner’s cottage. The Rev. John Swete, traveling the same road in 1796, considered this ostentatious rural retreat sufficiently picturesque to be reproduced in his travel journal. “There is a consistency and lightness in the arrangement of the house and its wings, which pleased me much,” he recorded, although he expressed reservations about “the comparative smallness of the upper windows” and found the wings “not perfectly appropriate to a Cottage with a straw-roof” (Gray 78).

“Cottage of Lardner Esq.” Reproduced by kind permission of Devon Archives & Local Studies, DHC 564M/F/6/143.

Mr. Lardner’s so-called cottage would not have found a place in William Gilpin’s collection of picturesque watercolors. Using thatch as a roofing material “makes it no more a cottage, than ruffles would make a clown a gentleman,” he pronounced, adding, “We every where see the appendages of junket and good living” (309). To fulfil picturesque requirements, windows could be casement or sashed, but not large; the lawn should be grazed, not mown; fountains, gravel walks, and fences were disallowed. Cottages familiar to Jane Austen, John Swete, and indeed the Dashwoods in their walks through the Devon landscape, were more likely to be irregular in construction, roughly thatched, and clothed in vegetation, their interiors confined, dark, and damp. The building material in this part of England was predominantly cob, a mixture of clay, stones, straw, animal hair, and dung. The regular appearance of Barton Cottage, together with its tiled roof, suggests that it is a brick house. With its four bedrooms, two garrets, offices, and two sitting rooms it sounds as comfortable as, if somewhat smaller than, the cottage at Chawton, where, soon after the move from Southampton in 1809, Jane Austen prepared Sense and Sensibility for publication.

Austen’s reworking of the novel might have begun as early as 1801, the year Richard Buller invited the Austens to stay at his rectory at Colyton on their removal from Steventon Rectory before taking up residence in Bath. A radical adjustment in Jane Austen’s own mental landscape at this time must have proved as painful as the Dashwoods’ on the loss of their much-loved home. It is to be hoped that she found some consolation in the gentle hills and valleys surrounding Buller’s rectory. Her father’s former pupil also held a perpetual curacy a few miles further west at Stoke Canon, where John Swete thought the village and church of picturesque merit, describing them as “pleasing objects in the centre of the most verdant pastures” (Gray 39). It is possible that Richard Buller took the Austens to Exeter and from there into the landscape “four miles northward” of the city.

A quick look into Richard Buller’s Devon connections provides several clues as to where Jane Austen might have traveled in this locality. Richard’s father, the bishop, was now dead, but his uncle, James Buller of Downes House near Crediton, eight miles westward of Exeter, was still alive. Marriages with Gould and Baring wives linked James Buller of Downes to Sir Stafford Henry Northcote, 7th Baronet, of Pynes House, at Upton Pyne, a short distance off the main post road between Exeter and Crediton. His grandson, the first Earl of Iddesleigh, claimed in 1900 that this house was the model for Barton Park, “and that I am writing these lines in the room in which Sir John Middleton ate his dinner” (Grey 380). The Northcotes were connected to the Quicke family at Newton St. Cyres, also located on the Exeter to Crediton road. Remember that “‘the two Miss Careys come over from Newton’” to Barton Park on the day of the Whitwell picnic (76).

“Pynes, the seat of H. Stafford Northcote, Bart.” with the River Exe. Reproduced by kind permission of Devon Archives & Local Studies, DHC 564M/F/1/203.

Attempting to pin down exact locations has always been a compelling exercise for some readers, a number of whom have taken their research into the realms of wishful thinking, but Barton place names do proliferate in this part of Devon: four near Stoke Canon; six near Upton Pyne; three near Cowley Bridge; two near Newton St. Cyres; and not far from Downes House are Creedy Barton, Fordton Barton, and Hookway Barton. Most of these place names denote the home farm of an estate and would not have appeared on any map Jane Austen might have consulted, but Barton Place is mentioned in Cary’s New Itinerary and Road Book (Cary 117) as a gentleman’s residence. And on the subject of spurious links, Barton Place, now a residential care home, has on its website the following claim: “Commanding views of the Exe Valley, Barton Place is immortalised as ‘Barton Park’ in Jane Austin’s ‘Sense and Sensibility.’” The property lies on the road between Exeter and the north and west of the county. If the Austens had traveled this route from Colyton in 1801, crossing the Exe at Cowley Bridge, they would have seen it. If not, within walking distance of Colyton Rectory Jane could not have missed Shute Barton, a sixteenth-century fortified manor house.

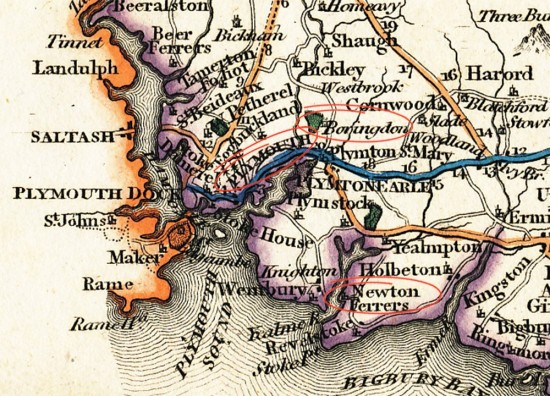

Enlarged extract from Cary’s New and Correct English Atlas (1821), showing the Plymouth area and Lord Boringdon’s estate, Saltram.

One more interesting point about Jane Austen’s use of place names: Mr Pratt’s school, where Edward becomes engaged to Lucy, is near Plymouth, in fictional Longstaple. Almost directly north of Plymouth on the map is Barnstaple, pronounced with a short a. Did this pronunciation give Austen the idea for an aural joke? By this analogy, Longstaple would be pronounced Longs-ta-pull, and Lucy certainly strives to “pull” Edward into her clutches, while he longs to pull away. There are no other “long” or “staple” place names in the Plymouth area, but just below the city there is a Newton Ferrers. It is worth noting too that very close to Plymouth is Saltram House, Norland Park in Emma Thompson’s film. It was the real home of Frances Parker, Lady Boringdon, who was widely rumored to be the author of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice. Jane Austen knew her, probably through her brother Henry, and evidently found the misattribution amusing, since she later sent the Countess a copy of Emma.

Saltram House.

Authentic-sounding place names, together with an unerring sense of what constitutes a home, are critical elements in Austen’s fiction. In Sense and Sensibility Marianne persuades herself that the loss of Norland will break her heart, but Willoughby’s arrival at Barton is enough to reconcile her to a very different emotional and physical landscape, and her previous home is all but forgotten. Both sisters shed tears on leaving Sussex, but little more is said of Elinor’s feelings of loss, beyond a regret that, unlike Marianne, she had “no companion that could make amends for what she had left behind” (64). The melancholy leave-taking is counteracted almost immediately at the beginning of chapter six by the Dashwood women’s first view of Barton Valley, through the window of their carriage: “it gave them cheerfulness. It was a pleasant fertile spot, well wooded, and rich in pasture” (33).

Three women traveling alone in September, despite the good weather, are not likely to be in an open conveyance, and other views from windows form their early impressions of the immediate landscape:

The situation of the house was good. High hills rose immediately behind, and at no great distance on each side; some of which were open downs, the others cultivated and woody. The village of Barton was chiefly on one of these hills, and formed a pleasant view from the cottage windows. The prospect in front was more extensive; it commanded the whole of the valley, and reached into the country beyond. The hills which surrounded the cottage terminated the valley in that direction; under another name, and in another course, it branched out again between two of the steepest of them. (34)

Fold upon fold of the landscape is perceived through a glass clearly, while layer upon layer of secrecy and deception come to be seen through a glass darkly as the narrative unravels. What constitutes a fine or extensive prospect in terms of landscape throws into focus the significance of prospect for other characters. For John and Fanny Dashwood, Mrs. Ferrars, and Lucy Steele, its scope encompasses the interconnected issues of marriage, money, and materiality. For Elinor and Marianne, struggling against this mercenary view of human relationships, the Barton landscape seems to promise extensive prospects, but it opens up only to close down and obscure. William Gilpin, traveling through the county in the 1770s noted a similar termination of focal range in the terrain: “intersected with several rivers, which run in vallies between opposite hills . . . so that all distance was shut out, and all variety of country intercepted” (244). Among the Barton hills, and later in London, Elinor and Marianne are in effect denied an unobstructed perspective of Edward’s and Willoughby’s true motivations, a shutting out that will affect their future prospects. Neither close to, nor at a distance, can either man’s intentions be discerned. When the sisters shut themselves off from each other, their limited disclosures and concealments add an extra layer of complexity.

Beyond the windows of Barton Cottage, our first glimpse of the sisters in the landscape comes in chapter nine. Marianne and Margaret venture outdoors despite the threat of bad weather and encounter Willoughby in the most dramatic of circumstances, emerging from the rain and wind to scoop Marianne into his arms. Emma Thompson’s 1995 film version makes the most of the scene by adding a thick mist. The most Jane Austen offers, on his leaving Barton Cottage, is: “he then departed, to make himself still more interesting, in the midst of an heavy rain” (51). It is enough to put us a little on our guard. While Marianne questions Sir John on Willoughby’s “‘talents and genius,’” sensible Elinor asks for more direct information: “‘But who is he? . . . Where does he come from?’” (52).

Apart from this first encounter and the carriage drive to Allenham, which happens off the page, scenes involving Willoughby and Marianne are always set indoors, where Willoughby’s influence leads to increasingly grave social improprieties, culminating in Marianne’s very public humiliation in London. On the day of the Whitwell picnic, rather than driving about the countryside, he heads straight for Allenham Court, the property he is to inherit on his cousin’s death, a house familiar to the Dashwoods only from the outside. Marianne is persuaded to penetrate this forbidden territory, thus violating Mrs. Smith’s privacy and violating too her own nature, in allowing her thoughts to take a materialistic turn, as she assesses Allenham in terms of real estate.

We never learn Willoughby’s “‘sentiments on picturesque beauty’” (57). The countryside in Devonshire provides little more than a glorified killing ground for him—remember that he carries a gun and is accompanied by two gun dogs when we first see him. Does he prefer both to hunt and elude women in more confined spaces? The enclosed urban environment of Bath provides the location for Eliza’s seduction; in London he tracks down a rich heiress and conceals himself from Marianne among the Bond Street shops.

It is not the object of this paper to give a description of the picturesque, but one or two references to William Gilpin’s writings are relevant to an understanding of Edward Ferrars’s response to his first view of Barton valley. The description of Edward’s arrival is Gilpinesque in itself, featuring foreground, distance, prospect, and animation:

Beyond the entrance of the valley, where the country, though still rich, was less wild and more open, a long stretch of the road . . . lay before them; . . . they stopped to look around them, and examine a prospect which formed the distance of their view from the cottage.. . .

Amongst the objects in the scene, they soon discovered an animated one; it was a man on horseback riding towards them. (99)

Although Gilpin did not appreciate many aspects of the Devon landscape—“Its very appearance on a map, shews, in some degree, its unpicturesque form” (244)—and although the golden color of ripe cornfields disgusted him on picturesque principles, he saw, as Edward did, value in the fertile soil. He wrote about the countryside around Exeter, Colyton, and Honiton, which is an extension of the landscape four miles northward of Exeter:

As the mist cleared away, and we saw more of the country around, its picturesque charms did not increase upon us. If the hills and dales, however, of which the whole country is composed, possess little of this kind of beauty, they possess what is better, the riches of soil, and cultivation in a high degree. If any valleys can be said to laugh and sing, these certainly may. Nothing can exceed either their tillage or their pasturage. (272)

If Edward Ferrars’s initial assessment of Barton valley—“‘these bottoms must be dirty in winter’” (102)—is hardly of the laughing, singing variety, the reader later comprehends his negative state of mind. The influence of his engagement to Lucy Steele causes him to look down at the mud, not up at the hills. Edward’s subsequent remarks are more considered: “‘I call it a very fine country—the hills are steep, the woods seem full of fine timber, and the valleys look comfortable and snug—with rich meadows and several neat farmhouses scattered here and there. It exactly answers my idea of a fine country because it unites beauty with utility’” (112).

Margaret Doody in her interpretation of Edward’s assessment of the Devon landscape, accuses him of “striking a pose as a practical man, a man of sense who sees in nature only what is fit to exploit. . . . Edward amid the hills of Devon is putting on an act, impersonating a pragmatic male proprietor” (235). I would argue the opposite, that far from assuming the exploitative attitude to the natural world held by the three landowning Johns—Dashwood, Middleton, and Willoughby—Edward is here revealing the true landscape of his mind, his yearning for a quiet, useful, rural existence within a community of “‘tidy, happy villagers’” (113). Unlike John Dashwood, arch-blighter of prospects, natural, communal, and familial, Edward values a “‘fine prospect’” (113) that encompasses the promise of plenty for all who live within it.

William Gilpin’s view is not a hundred miles away from Edward’s appreciation, and on this occasion it is, ironically, Marianne’s passion for “‘rocks and promontories, grey moss and brushwood’” that is misplaced (112). The locations to yield such picturesque stage props are the isolated stretches of Dartmoor and places on the road along which Edward travels between Plymouth and Exeter.

Enlarged extract from Carey’s New and Correct English Atlas (1821), showing Edward’s route from Plymouth to Exeter.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

The fertile hills and valleys of the Exe can supply no equal grandeur, but given Marianne’s self-delusional tendencies and love of drama, it is not surprising that she interprets the surrounding landscape in this wishful-thinking way: “‘here is Barton valley. Look up it, and be tranquil if you can. Look at those hills! Did you ever see their equals? . . . And there, beneath that farthest hill, which rises with such grandeur, is our cottage’” (102). It is wish fulfilment too that hastens Marianne’s steps towards the man on horseback on the long stretch of road, believing him to be Willoughby returning from London. Elinor, conversely, does not immediately recognize Edward because she lacks any certainty in his affection and cannot allow herself to hope. The external scene might be described as “more open”; the internal state of the characters is anything but. Off his horse, Edward demonstrates a singular lack of animation, a lowness of spirits caused by his regrettable connection with Lucy Steele, which, when the true state of affairs is eventually “‘decided and open’”—to borrow a phrase from Emma (502)—casts a different light on Edward’s first reaction to the Dashwoods’ proposed removal from Norland to Devonshire: “Edward turned hastily towards [Mrs. Dashwood], . . . and, in a voice of surprise and concern, . . . repeated, ‘Devonshire! Are you, indeed, going there? So far from hence! And to what part of it?’” (29).

The process of illuminating the real nature of Edward’s situation happens, appropriately enough, in the open, as Lucy and Elinor walk the half mile from the Park to the Cottage. Lucy’s revelations close down Elinor’s romantic prospects as the first volume comes to an end. For the following fourteen chapters of the second volume, set primarily in London, Elinor is distanced from Marianne by the weight of this disclosure, while Marianne’s concealments have already begun, following Willoughby’s departure from Barton. The nature of the landscape stands as a metaphor for secrecy and division; the deep lanes, hills, and valleys where Marianne can hide to indulge and feed her grief: “If her sisters intended to walk on the downs, she directly stole away towards the lanes; if they talked of the valley, she was as speedy in climbing the hills, and could never be found when the others set off” (99).

While solitary walks in the wild areas of the grounds at Cleveland, the Palmers’ house in Somerset, “where the trees were the oldest, and the grass was the longest and wettest” (346), bring on the fever that almost kills Marianne, recovery is gradually effected among the Devon hills. At first, on her return to Barton, the familiarity of every tree and field sparks painful recollections, but eventually the landscape becomes a place of healing where greater openness in the sisters’ relationship is nurtured. The landscape of Marianne’s mind is sufficiently altered that she can view more or less calmly “the important hill” behind the house where she fell and first saw Willoughby (389). She envisages long walks into the local landscape over the coming summer and is encouraged by Elinor to talk about past expectations and sorrows while having little faith in improved prospects for herself.

Intelligence of the new Mrs. Ferrars’s departure from the New London Inn in Exeter obliterates Elinor’s last shred of hope: “She now found, that in spite of herself, she had always admitted a hope, while Edward remained single, that something would occur to prevent his marrying Lucy.” What Edward had felt “on being within four miles of Barton” she cannot bear to determine, choosing instead to close her eyes and mind both to his prospects and her own: “she knew not what she saw, nor what she wished to see;—happy or unhappy,—nothing pleased her; she turned away her head from every sketch of him” (404˗05).

When Edward arrives in person at Barton, again on horseback and again mistaken for someone else, he comes to do away with uncertainties and establish his unquestionable identity as Elinor’s lover. The landscape serves its final purpose in providing the necessary bracing air and dry lanes for Edward to “walk[ ] himself into the proper resolution” (409) to ask Elinor to marry him.

Both sisters ultimately find their happiness in the neighboring county of Dorset, where “rather better pasturage” (425) for Elinor’s cows and practicalities such as the convenient proximity of the butcher’s shop and the size of the mulberry harvest will form their concerns as married women. But it is the Devon landscape that has shaped them emotionally. Jane Austen does not reveal whether Elinor and Marianne accept their suitors indoors or out, but, given how many of her subsequent heroes propose in the open air, let us create a pleasant prospect for ourselves where hearts and minds are opened among the enfolding hills.