In the Fall of 2020, my students at Stanford Online High School and I did something that, until then, I didn’t know could be done in a high-school English class. We co-authored an original article on Jane Austen, and people read it. Then we did something that I was sure couldn’t be done. We published a book on Jane Austen, and more people read it. Some, gratifyingly enough, even paid what Austen once called “pewter” for it (30 November 1814). We’ll have plenty more to say about both those works, but ultimately this article is about something bigger. It’s about rethinking our whole approach to the teaching of writing and research in upper-high-school and college English classes, at least when Jane Austen is the author under consideration. To put the thesis up front (I am a high-school teacher, after all), we need to be doing less assigning and grading, and more hands-on collaborating. We should be writing and researching with our students, creating pieces together, and, whenever possible, offering them to the public.

This article, too, is a collaboration: three of the students who took part in the Austen projects have joined me on it. While we are all in accord on the value of student–teacher collaborations, we each have our own perspective and points of emphasis. By sharing the authorship of this piece, we can offer a richer account of the possibilities afforded by this mode of learning.

The what: an article, a book, and even a talk

I’ll begin with an overview of the projects themselves. In the summer of 2020, as I was designing a unit on Northanger Abbey for my senior-level course on love stories, I came across an obscure poem called “Bath: An Adumbration in Rhyme,” by the minor poet John Matthews (1755–1826). The poem is a satirical picture of Bath published in 1795, two years before Austen’s first known visit to the city. My initial plan was simply to have students read the poem as a way of learning about the setting of Northanger Abbey (1817), which also takes place in the 1790s. When I discovered the poem was virtually untouched by scholars, however, I began to entertain the idea of an original article, co-written by the students and me, that would use the poem to shed new light on Austen’s Bath novels. The question was: where would we publish such an article?

I didn’t think an academic journal would be right for the project. Some solid, readable primary research was what I envisioned, and I worried that traditional journals (if they didn’t balk at the very idea of student authorship) would want extensive engagement with secondary literature as well. Instead, I tried another route. I contacted Vic Sanborn, editor of my favorite Austen blog, Jane Austen’s World, and asked if she would be interested in the article. Not only did she agree to publish the piece when it was ready, she also offered to speak to the students about Georgian Bath and the art of blog-publishing more broadly. By the time the semester began, the “Adumbration” project was central to the aims of the course. It was a way to explore the context of Northanger Abbey more deeply, and it was an opportunity to make a real contribution to literary scholarship, learning the ropes of researching, writing, and editing along the way.

The work proceeded in stages. Before we began, students had the benefit of a visit from a Stanford librarian, who showed them how to access the university’s online resources. Vic Sanborn also visited class, as did tour-guide Tony Grant, who gave us a photographic tour of Georgian Bath. Then, as a group, we brainstormed all the things we would need to do before we could write an informed, relevant article on our poem. These tasks included:

- Researching the life and work of John Matthews

- Learning more about Austen’s time in Bath

- Familiarizing ourselves with other satires of Bath

- Collecting public-domain images of Georgian Bath

- Tracking down and glossing the poem’s many allusions to long-forgotten people, places, and customs

I broke the class into groups of three to four, with each group responsible for one of the above tasks, except for the final one, to which every group contributed. Then, I fleshed out each of those general tasks with more specific research questions. For the first, those included: “what else did Matthews write?” and “were there any contemporary reviews of his work?” I discovered early on that the more specific I could be about research tasks, the more productive our efforts were.

In the last couple weeks of class, we turned our attention from exploration to consolidation. Matthews’s poem describes a typical day in the life of a Bath tourist, from the morning meet-up at the Pump Room to the famous public balls that stretched late into the night. We decided to match that structure to give readers a sense of how Catherine Morland and, indeed, Austen herself, may have spent some of their days in Bath. Each group was responsible for a section of the article: morning, afternoon, and evening. I wrote the introduction, and the groups wrote the body, with several rounds of feedback from me. I made some final touch-ups during winter break, and then we sent the draft to Vic, who published it several weeks later under the title “A Day in Catherine Morland’s Bath” ( https://janeaustensworld.com/2021/01/04/a-day-in-catherine-morlands-bath/). Here is an excerpt from the article, written mostly by my former student and current co-author Varsha Venkatram.

As work was wrapping up on the article, some of us felt there was more to say about Matthews and his “Adumbration.” So we embarked on an even more ambitious project: creating a critical edition of the poem, specially designed for readers of Jane Austen. That part of the project was accomplished outside class, with about half the students staying on to complete it. The book that we eventually published, Bath: An Adumbration in Rhyme. A Critical Edition for Readers of Jane Austen (https://pixeliapublishing.org/bath-an-adumbration-in-rhyme/), reintroduced the public to John Matthews and made some original contributions to the study of Jane Austen. For example, it is the first work to seriously explore Austen’s relationship to the genre of the anapestic Bath satire, which was popular in her day and clearly influenced her work. Sometimes this influence is quite specific: The New Bath Guide (1766) by Christopher Anstey (1724–1805), for instance, likely furnished the model for Isabella Thorpe (see Kate Snyder’s piece below in the section entitled “Advantages of Student–Teacher Collaborations”). Sir Walter Elliot, meanwhile, is an elderly twist on a stock character of Bath satires: the macaroni, or foppish, overdressed young man.

More generally, and more importantly, the overall tone of this light-hearted genre seems to have influenced Austen. Bath satires, including Matthews’s “Adumbration,” were generally playful and good natured, a marked departure from the Juvenalian fury of some earlier English satire. The reader is invited not to judge Bath but to laugh at it (and perhaps go and see for herself). That is the attitude we usually find in Northanger Abbey. For all Austen’s mockery of the town, she does not seem harshly disposed toward it. Her heroine, Catherine, certainly enjoys the sights and sounds, and if her admiration for Bath is excessive at times, it is also fundamentally endearing. Meanwhile, the sternest critic of Bath in the novel, General Tilney, is one of the least likable characters Austen ever devised. In short, Austen’s relationship to the Bath satire—a largely forgotten body of poetry—is a reminder that as we hunt for her satirical influences, we would do well to range beyond “greats” like Pope, Swift, Fielding, and Smollett. There are discoveries to be made among the fads and ephemera of her literary world as well.

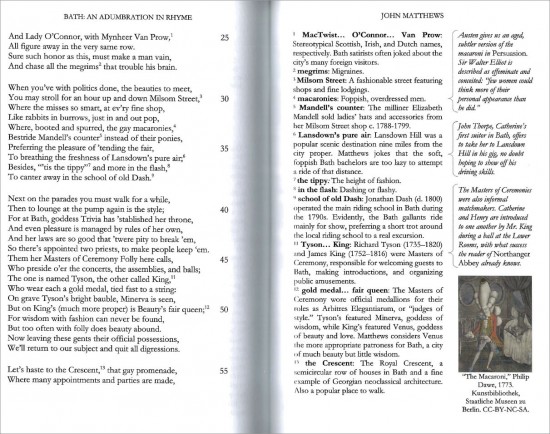

In addition to a biographical and a contextual essay introducing the poem, our edition of “The Adumbration” has a unique system of notes. The students’ idea was to have two columns of notes on the page opposite the text: the first for general commentary, and the second for connections to Austen’s novels. That way, each page has something for the curious Austen reader, our target audience. In the sample spread below, for example, there is a general note on the “Masters of Ceremony” (ll. 45–47) explaining the social duties of those important Bath officials. Then, there is an additional note reminding Austen readers that Catherine is introduced to Henry Tilney by James King, Master of Ceremony for the Lower Rooms—a hint that these organizers of public amusements were also informal matchmakers.

Ultimately, we were able to publish the book thanks to the ingenuity of my colleague Tom Hendrickson. Tom, a Latin teacher at Stanford OHS, had the idea to found a publisher that would serve as a platform for these kinds of student–teacher collaborations; he himself creates editions of Latin texts with his students. The general strategy was to publish each book in two forms. The first would be an open-access e-text, freely downloadable from our website, pixeliapublishing.org. The second would be a print-on-demand paperback edition. The two would work together: the free e-text would ensure maximum accessibility, our main goal, while the paperback would bring in the revenue to cover our very modest expenses. He and I, together with two other teachers, launched Pixelia Publishing in 2021. Bath: An Adumbration in Rhyme, published in August of that year, was its second release.

The book has met with an encouraging reception. Positive reviews have appeared in several Austen-related publications, including JASNA News (Barchas). It has sold over one hundred print copies and has been downloaded a few hundred times as well. Last summer, the whole project, including the article, was a finalist for the 2022 North American Society for the Study of Romanticism (NASSR) Pedagogy Contest. The book has also led to some other scholarly opportunities. For instance, last December, four students and I presented our research to a group of around fifty Janeites at the annual gala of JASNA NorCal.

The why: advantages of student-teacher collaborations

By Varsha Venkatram

Why spend several months researching an obscure poem from the 1700s? The short answer is that I was interested. I was intrigued by Jane Austen, by reimagining the city of Bath as it must have been in the eighteenth century, and by doing schoolwork that I wasn’t used to.

The long answer is that other people were interested. I don’t only mean Dr. Wiebracht and his infectious enthusiasm, or my classmates (all of whom made this project a joy to work on), but the Austen-reading public. We, as high-school students, were given the opportunity to interact with and learn from real Jane Austen aficionados both pre- and post-publication—from blogger Vic Sanborn to tour guide Tony Grant to a variety of members from JASNA NorCal. When the audience for our work became larger than a teacher or classmate, the importance and relevance of that work felt clearer. We weren’t just writing for a grade, or to get an assignment over with, but to contribute something to an already existing Jane Austen community. Prior to publication, I felt motivated to work on the project because of that prospective audience who would give us—and has given us—genuine thoughts and feedback. I’ve often returned to the site of our original article to see if there are any new comments: each time there is one, I’m personally excited and professionally motivated.

This project also helped me acquire academic skills that have been essential in college: how to seek out and properly use various resources (see Kate Snyder’s section below), how to navigate the publication process, how to conduct in-depth and detailed research, how to publicize one’s work, and much more. Many classes and careers require such skills, not to mention the collaborative skills I learned from working so closely with my peers and my professor. To be sure, commitment to a project like this one requires enthusiasm on the part of the students, and it requires them to already have experience in English essay writing. Yet I’m convinced that there are many students out there who would be truly excited by such a project—and, as I did, find a much greater interest in Austen than they would from reading a book and writing yet another essay. The article, the book, the talk were fun, but also practically valuable because of the skills we learned and the curiosity it incited in us about Jane Austen, research, and English classes.

By Kate Snyder

For me, the main value of this project lay in the research skills I learned, which have allowed me to appreciate literary works in a deeper way. Before this project, I had no idea what it meant to do research in the humanities. The feeling of scouring library resources and materials to answer research questions about a text was something novel, and something I can’t wait to pursue more in college. I’m now intending to focus on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literature, and I specifically seek courses each semester that include reading lists featuring Austen. For me, researching Matthews’s “Adumbration” transformed my experience reading Northanger Abbey from a typical assignment to something deeper—I became wholly enthusiastic about the novel and felt more connected to it.

One of my tasks was to research the genre of the Bath satire, focusing on Christopher Anstey’s New Bath Guide (1766), the work that started the satirical trend. Comprised of a series of letters, the New Bath Guide follows the adventures of a gullible party of visitors who embrace the city’s delights wholeheartedly but who eventually learn that it isn’t quite the paradise it seems. It was both motivating and exciting to find parallels between the New Bath Guide and Northanger Abbey. To take one example, the character Jenny in the New Bath Guide falls head over heels for Captain Cormorant, meeting him in the Pump Room in the mornings and delighting in walks and dances with him. Similarly, in Northanger Abbey, Isabella Thorpe flirts with Captain Tilney in the Pump Room and at nightly balls, and just as Isabella is ultimately jilted by her captain, Jenny is heartbroken to discover the truth of Captain Cormorant’s deceitful nature and dubious history. Since the New Bath Guide was still immensely popular in Austen’s time, it’s not unlikely that Austen found inspiration in Anstey’s subplot for her own.

Discovering this parallel between Austen and Anstey gave me a personal connection to Northanger Abbey. It also helped me situate the novel within a larger literary context. I now see the novel as part of the genre of the Bath satire and not just as a parody of the gothic, its usual framing. Somehow knowing that she used elements of earlier literature as well as her own observations makes Austen seem more relatable and less isolated.

By Macy Levin

If I had to describe my experience working on Bath: An Adumbration in Rhyme in one word, I would pick “unconventional”: “unconventional,” because when we finished our unit on Northanger Abbey, I never expected to work on and publish a book discussing a humorous little poem we read in class and its relation to the world of Jane Austen; “unconventional” because our book turned into a presentation before an audience of supportive, dedicated Janeites; and “unconventional” because I am now writing a segment for a scholarly article reflecting on the times we’ve had. In short, the project was a refreshing change of pace, allowing me to do work that I never thought would be part of an English class.

One of my roles in this project was that of biographer. When I first read John Matthews’s “Bath: An Adumbration in Rhyme,” I knew nothing about his life—let alone his family affairs—but, by the time our literary expedition in the world of Matthews and Bath came to a close, I had discovered much about his wife, Elizabeth Ellis (1757–1823), her background, and the lives of his children (one of whom, Charles Skinner Matthews [1785–1811], was close friends with Lord Byron [1788–1824]; the two exchanged letters, and I was lucky enough to find snippets of their correspondence in my research).

Alongside researching Matthews and Ellis, I also designed the cover. I wanted to capture the vibrant city of Bath itself, as well as the themes of Austen’s work. For the latter, I drew a spire of foxgloves along the spine, representing the intimacy and femininity that is present in all of Austen’s novels. For the former, when deciding on images, we rifled through a selection of etchings featuring Milsom Street, the central shopping way in Bath; eventually, though, we settled on a sketch of the Pump Room. The Pump Room was the central gathering place of Bath tourists. It was where the news of the day was shared, gossip was spread, and many came from around England and beyond to drink the healing waters of Bath. Thus, it seemed only right for it to function as the welcome to our work.

By Ben Wiebracht

Student–teacher collaborations have the potential to transform how we teach writing and research. Both in high school and college, students generally learn to write by working in genres (such as the five-paragraph essay) that are not used in the real world and whose audience is minuscule—usually the teacher and no one else. To be sure, we teachers might ask students to imagine a broader audience for their work, but that’s a tough sell. Students know good and well that no one reads or writes five-paragraph essays outside school. And even if they were able to imagine such an audience as a theoretical possibility, the teacher-audience, wielding GPA-altering power, remains the hard-to-ignore reality. In this stressful and artificial environment, students gradually absorb the unhelpful lesson that academic writing is an intellectual performance that one puts on for a grade, rather than a sincere effort to inform and persuade an open-minded public.

It does not have to be this way—certainly not when teaching Jane Austen. Austen, after all, has a massive popular readership. There are blogs, clubs, and websites that maintain lively conversations about her life, times, and career. And perhaps because these conversations take place largely outside formal academia, their curators aren’t squeamish about the idea of opening them up to students. Indeed, they are often eager to.

Varsha (see above) describes how it feels, as a student, to write for a real audience. I’ll simply say that, as a teacher, I found my students writing more naturally and gracefully once there were actual readers to address. Instead of worrying about the pinched “rules” of the school essay (thesis at the end of the intro, two quotes per paragraph, each body paragraph nodding at the thesis, no first-person pronouns, etc. etc.), they were now addressing regular people who liked and knew a lot about Jane Austen and letting that audience inform their structural and stylistic choices.

Meanwhile, when I ceased to be the sole audience for my students’ work, I was able to be a better, more involved teacher. In so many fields, from carpentry to medicine to the culinary arts, the best learning happens through collaboration, with the teacher and the learner working together to make or accomplish something. As a fellow writer and researcher, I could demonstrate those crafts for my students instead of just speaking about them. That’s not to say, of course, that everything I wrote during this project was a model of fine scholarly composition. Indeed, on more than one occasion students advised me in workshops not merely to change something I had written, but rather to “try again.” Those moments also had educational value: they sent the message that all writers, not just student-writers, draft, revise, take feedback, and sometimes go back to the drawing board.

The how: four tips for setting up a public-facing student–teacher collaboration

1. Varsha Venkatram: The project should replace, not add to, conventional assignments.

We students worked on this project during either our junior or senior year of high school, two of the most busy and stressful years of a student’s life. It would be unrealistic to expect such overwhelmed students to dedicate their time outside of school to this type of endeavor, even if they were truly interested. Dr. Wiebracht, however, made it possible by having our work for the project replace conventional essays and write-ups and by removing the stress of a grade. In addition, we had clear checkpoints and deadlines, which made the work much more manageable. The research we conducted and the writing we did were only feasible because of that awareness Dr. Wiebracht had of our schedules and workload.

2. Kate Snyder: Show students in advance how to navigate their library’s online resources.

Learning how to use library resources was essential to the project. A Stanford librarian showed us how to navigate the extensive databases and online catalogs. This session was particularly helpful in getting us started, since before this visit, I was unaware of both the extent of these resources and how to use them. These skills became invaluable in research projects for other classes as well. It has been especially gratifying to use these skills now in college, where I have access to a physical library just across campus.

3. Macy Levin: Don’t underestimate your students.

Students are intelligent and capable creatures, but whether we recognize that fact depends in large part upon the attitude of our teachers. For a project such as this, Dr. Wiebracht’s enthusiasm and trust in us (that we were responsible enough to finish tasks on time and provide substantial results) were just as motivating as the opportunity itself. The moral of the story: don’t doubt your students. We don’t need grades and unnecessary stress to hold us accountable; instead, as is seen with our work on the “Adumbration,” respect, trust, and pure passion create a far more motivating learning environment.

4. Ben Wiebracht: Divide up tasks thoughtfully.

In divvying up the workload for projects like this, my advice to teachers is to give students opportunities for both individual work and collaborative work with you. That way they have the benefit both of recognizing their own special contributions in the final product and of seeing how you, as a more experienced writer and researcher, go about your business. Whether you have the student work independently or with you should be determined by the complexity and difficulty of the task. To take our critical edition as an example, I was able to delegate the writing of most of the notes directly to students. They did the research and final composition, and my involvement was limited to consultation and feedback. I assigned stretches of the introduction in the same way. Carolyn Engargiola, for example, was in charge of researching the life and career of Christopher Anstey, a major influence on John Matthews and a likely minor influence on Austen, so it made sense for her to write the section on him in our introduction. Students selected images, compiled author timelines, edited the raw text of the poem, and designed the cover largely on their own as well.

Some tasks, though, were a taller order. In those cases, I would take the lead and involve students in other ways. One of our agenda items, for example, was to survey the genre of the Bath satire so we could find out in what ways our poem was typical and in what ways exceptional. Distilling an entire genre of poetry to its definitive features seemed like a lot to ask of a high-schooler, however exceptional. To get the ball rolling, I tracked down ten or so specimens of the genre, read a few, and noted some preliminary similarities—things like mockery of spinsters and widows and complaints about the mingling of social classes. Students were responsible for reading the other specimens, summarizing them, and determining whether the preliminary similarities I had identified applied to their particular text. We met up as a group to compare our findings and decide what general claims to make about the genre in our introduction. (For example, thanks to our collective work, we were able to conclude with confidence that Bath satires did often mock older single women and were generally anxious about class mixing. Was Austen’s Persuasion [1817], with its sympathetic picture of a widow living in Bath and its criticism of class snobbery, a conscious rejection of these precedents?) I then drafted the section, and the students offered feedback and revisions.

In short, a good approach to workload management is to let students work independently when possible, to let them work with you when not, and to do as little as possible entirely on your own.

![]()

The rise of blogging and print-on-demand publishing, the mass digitization of texts, and the continued growth of the online Austen community have created the perfect conditions for this kind of work. In fact, Bath: An Adumbration in Rhyme is just the first in a planned series called Forgotten Contemporaries of Jane Austen. Next up: a critical edition of the hilarious Tour of Doctor Syntax in Search of the Picturesque (1812) by William Combe (1742–1823), a poem that, judging from one of her letters, apparently tickled Austen herself (2–3 March 1814).

There are exciting collaborations underway in the wider world of Romantic studies as well. For brevity’s sake I’ll just name a handful.

- Juvenilia Press (https://sam2.arts.unsw.edu.au/juvenilia/), based out of the University of New South Wales, publishes annotated editions of the immature work of major authors, with Jane Austen as their “mainstay and . . . patron saint” (McMaster and Kortes-Papp). Undergraduate and graduate students, working under the mentorship of experienced academics, do much of the work and are credited as editors.

- As part of a class taught by Shef Rogers and Tom McLean, undergraduate students at the University of Otago recently published a collection of hitherto unprinted letters by eleven eighteenth- and nineteenth-century women writers. This collection, In Her Hand: Letters of Romantic-Era British Women Writers in New Zealand Collections (2013), has sold over 150 copies and has been acquired by several research libraries. I’ve read it myself, and it is an admirable piece of scholarship—showing new continuities between the public and private lives of these norm-defying women.

- Students of Michelle Levy at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia also recently published an edited collection of letters by eminent early-nineteenth-century women (https://olem.omeka.net/exhibits/browse). They began with an album of such letters collected by the antiquarian William Upcott. They transcribed and annotated the individual letters, wrote short bios of the writers, and then posted their work online in a publicly available form. Levy was a co-winner of the 2022 NASSR Pedagogy Contest for her direction of this project.

- Dahlia Porter, working with curators at the Hunterian Museum, taught a class at the University of Glasgow called Literature and Collecting that allowed students to examine material artifacts from the Romantic period alongside literature. The students wrote essays on those objects that analyzed and critiqued the museum exhibits, which were subsequently reinterpreted through a community-led installation at the Hunterian Museum entitled “Curating Discomfort.” Porter was the other co-winner of the 2022 NASSR Pedagogy Contest.

As lovers of Jane Austen, we should be surprised by none of this. After all, aren’t her novels generally about intelligent, insightful young people who go underappreciated for a time but whose full worth is revealed in the end? The old assumption that only graduate students and university faculty have the chops to do real literary scholarship looks shabbier by the year. Younger students—including high-schoolers—also have significant contributions to make. We teachers should be the first to recognize and cultivate this potential.