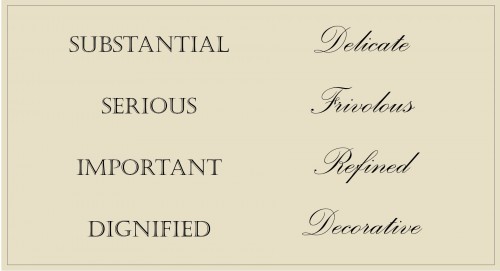

During the Georgian era, women and men alike had a great interest in architecture, interior design, and fashion, and there was an expectation that the concepts of femininity and masculinity would be reflected in these spheres.1 Gender was manipulated as a marketing tool by designers and manufacturers of domestic goods, and affluent men’s and women’s clothing began to differ in functionality and materials more than they had in the past. The association with masculinity of the substantial, serious, important, and dignified and of the delicate, frivolous, refined, and decorative with femininity pervaded descriptions of material culture. This essay will explore how decorative arts, interiors, and clothing presented in Austen’s novels, particularly those in Northanger Abbey that are connected to General and Henry Tilney, speak to the roles of women and men in her era.

In studying his and her account books of the Georgian period, Amanda Vickery has found definite ideas about what should be under the control of men and women in decorating the domestic sphere.2 Men generally handled the large expense of major redecoration efforts; they undertook whole-house commissions and large orders for sets of furniture like chairs, beds, and sofas. They also purchased items that spoke to their personal needs and entertainments as gentlemen, such as shaving stands and gaming tables. Women were responsible for the category of property known as “moveables,” which was associated with the “marriage portions of daughters and with bequests granted to widows” and included ceramics, textiles, and the furniture to hold them, such as cupboards and chests (Ulrich). The types of objects controlled by women are reflected in the “household linen, plate, china, and books, with an handsome pianoforte of Marianne’s” (SS 30), moved from Norland Park to Barton Cottage for the Dashwood women and which the meanspirited Fanny begrudges them. This category also includes a breakfast set, which Fanny says is “‘[a] great deal too handsome, in my opinion, for any place they can ever afford to live in’” (SS 14–15).

Figure 2: Thomas Sheraton, “Gentleman’s Shaving Table” (1803) |

Figure 3: Spode, Tea and Breakfast Service (1812–1815) |

Acquisitions of domestic objects could be made by men and women in accordance with the public roles they fulfilled. For instance, although the collecting of china objects was considered a female enterprise, record books indicate that both men and women purchased ceramics. As head of the household, men commissioned status items like dinner services that bore the family heraldry. In their roles as hostesses and housekeepers, women bought things like breakfast and tea sets and single pieces to replace breakages (Anderson 36). A wife’s level of input on domestic decoration could vary from marriage to marriage, and couples often worked together to make aesthetic decisions about their homes and the objects that filled them. Judith Anderson relates the example of a man who approved the design of the crest on his dinnerware, while his wife chose the shapes (34). Perhaps this type of dynamic was at play when Edward Austen Knight, whose wife was no longer living, brought his daughter with him to Wedgwood’s in London. As noted in an 1813 letter from Austen to her sister, Cassandra: “my Br & Fanny chose a Dinner Set.—I believe the pattern is a small Lozenge in purple, between Lines of narrow Gold;—& it is to have the Crest” (16 September 1813). Austen also gives us the example of Elinor and Edward Ferrars in Sense and Sensibility making plans together for changes to the Parsonage at Delaford, choosing wallpapers, deciding on ornamental plantings, and putting in a curved carriage drive.

Figure 4: Knight Family Dinner Service (c. 1813)

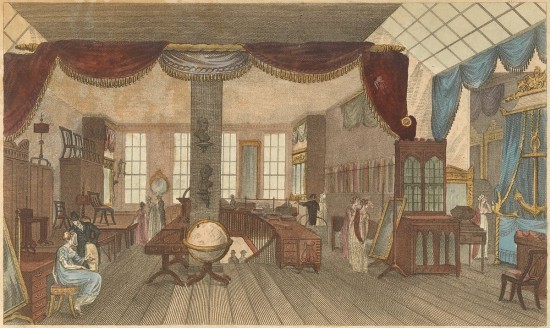

Scholars of Georgian material culture have found a large body of evidence that men found just as much pleasure in shopping as women did (Styles and Vickery 163; Germann and Stroble 3). Women, however, were responsible for the mundane household shopping and basic provisions and therefore seemed to spend more time in the marketplace. This separation led to the discourse of characterizing shopping as a female activity, thus exposing women to accusations of overindulgence, greed, vanity, and materialism. The same type of allegations of feminine vice had traditionally been levelled against those who strove to be fashionably dressed. Clothing historian Aileen Riberio has posited that a negative association of fashion with women is due, at least in part, to the fact that women’s relative lack of financial power made them more dependent on their sexual attractiveness than men (16). A passion for dress was indicative of being overly concerned with appearances and signaled feminine extravagance and vanity.

Figure 5: Messrs. Morgan and Sanders’s Ware-room (1809)

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Figure 6: “Promenade in Kensington Gardens” (1804)

(Click here to see a larger version.)

In Austen’s work, most of her characters who spend too much time shopping and/or paying attention to their dress are women. Isabella Thorpe longs for a pretty hat with fashionable coquelicot ribbons and later wants to show it to Catherine Morland as an excuse to pursue two young men down the street. Mrs. Allen is concerned about the safety of her gowns when in crowded assemblies and is as proud of them as her friend Mrs. Thorpe is of her children. Charlotte Palmer’s “eye was caught by every thing pretty, expensive, or new; [she] was wild to buy all, could determine on none, and dawdled away her time in rapture and indecision” (SS 187–88). Lydia Bennet purchases a bonnet that she knows is ugly for the sake of acquisition alone. Harriet Smith, “tempted by every thing and swayed by half a word, was always very long at a purchase” and can’t decide on a muslin (E 251). Mrs. Elton disingenuously claims to “‘have the greatest dislike to the idea of being over-trimmed—quite a horror of finery’” (327) but boasts about her pearls and is shocked at how “‘[v]ery little white satin, very few lace veils’” were to be seen at the wedding of Emma Woodhouse and Mr. Knightley (528).

Figure 7: Ivory Toothpick Case (1801–1850)

(Click here to see a larger version.)

It is interesting to note that in the satire of the era, the male shoppers who are singled out as ridiculous tend to be young bachelors (Styles and Vickery 5).3 Austen takes up this type in the character of Robert Ferrars, who spends an excessive amount of time in giving orders for his toothpick case while other customers, including Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, are waiting to be served. When he is finished, he “bestow[s]” a glance at the sisters, “but such a one as seemed rather to demand than express admiration, [and] walked off with an happy air of real conceit and affected indifference” (SS 251). D. A. Miller has pointed out that Robert’s time spent shopping for a trifle is done with “the cool, easy, altogether undisputed authority of a man who assumes—and imposes on all around him—the full importance of this silly-feminine thing,” and that his authority is “so magisterial that even devirilization cannot lessen it” (19, 20).

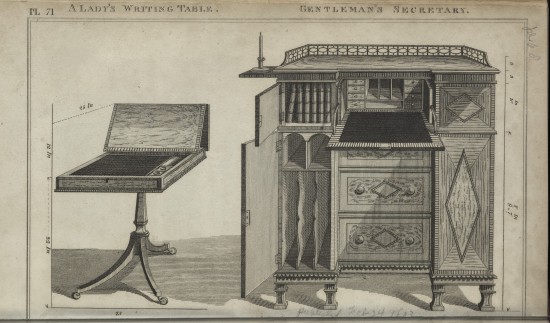

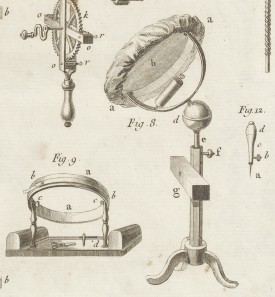

Ideas about feminine frivolity and masculine seriousness can also be seen in domestic objects and the spaces into which they were placed. While furniture suited to male or female needs was not new, the specific titling of pieces by gender was a Georgian innovation. Beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, London cabinetmakers such as Thomas Chippendale published books showcasing their furniture designs, which were categorized by function and style. The additional classifications of “lady’s” and “gentleman’s” were applied to dressing chests and stands, desks, tables, and cabinets. The trend was still being followed as the century turned, with Thomas Sheraton including gender-specific items in his Cabinet Dictionary editions that began in 1793. Plate 71 from the 1803 edition shows the great difference in size between his “Lady’s Writing Table” and the “Gentleman’s Secretary.” Vickery comments that this furniture “presumes that women’s writing was a delicate drawing room performance, while men’s business was altogether more official and substantial” (280). She also points out that the popularity of this gendered furniture signals an acceptance by consumers of the “conventional ideas of masculine importance and female delicacy” (288).

Figure 8: Thomas Sheraton, “A Lady’s Writing Table” and “Gentleman’s Secretary” (1803)

(Click here to see a larger version.)

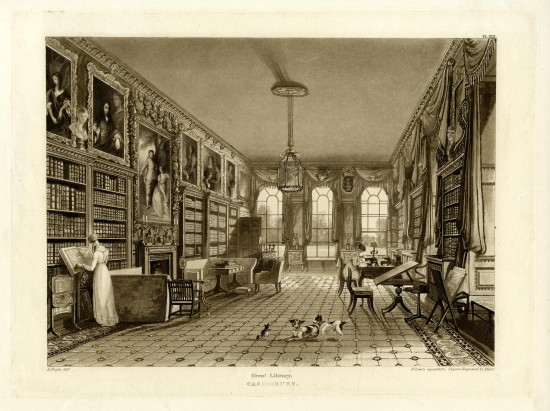

Although not gender-specifically named, the rooms in which furniture was used also held gendered connotations. The function of interior spaces was changing throughout the Georgian and Regency eras, each room type now being codified by function and decoration, both of which could be seen as masculine or feminine. For instance, in the 1803 edition of his Cabinet Dictionary, Sheraton specified a “bold, massive and simple” look for the entrance hall to impress visitors upon their arrival with the family’s status (qtd. in Kinchin 14). Furnished “in imitation of the antique” and decorated with portraits of “men of science and erudition” (qtd. in Kinchin 14), a gentleman’s library signaled his love of classical learning and intellectual pursuits. These masculine rooms could contain nothing “trifling” that would detract from the serious atmosphere found within. This idea is alluded to in the description of Mr. Bennet’s library, where “he had been always sure of leisure and tranquility; and though prepared, as he told Elizabeth, to meet with folly and conceit in every other room in the house, he was used to be free from them there” (PP 80). Sheraton allowed “little affairs” and “innocent trifles” only in the more feminine music or dressing rooms, where “anything of a scientific nature” like books or globes was prohibited (qtd. in Kinchin 14). Juliet Kinchin states that “the keynote of the masculine rooms was serious, substantial, dignified (but not ostentatious) and dark-toned. By contrast, the more feminine spaces were characterised as lighter or colourful, refined, delicate and decorative” (13).

Two rooms that truly exemplify this gender binary are the dining parlor and the drawing room. The former was considered a masculine room because once the women had “withdrawn” to the latter after dinner, men spent quite a long time seated at the table engaged in homosocial conversation. For instance, in Mansfield Park, Fanny Price is worried when Sir Thomas and Edmund Bertram “sat so much longer than usual in the dining parlour, that she was sure they must be talking of her” refusal of Henry Crawford’s offer of marriage (387).

Figure 9: Dining Room, Chatsworth House

According to Sheraton, the dining parlor (also called the dining room) should be large and of “a very august appearance” (qtd. in Kinchin 14). The furniture should be “bold, substantial and magnificent” and include a “large” sideboard, a “handsome and extensive” dining table, and “respectable and substantial looking” chairs (qtd. in Kinchin 14). Bold paint colors on the walls complemented the gilt frames on the artwork hung for the admiration of the guests (Yorke); these were often family portraits, thereby displaying, as Kinchin remarks, the male’s “heredity credentials” (14). Other masculine dining-room appointments included dining sets that featured the crest of the male line, such as the Knights’ ceramic dining service mentioned above and the one in silver shown here, which was commissioned by George, Lord Anson, from one of the foremost silversmiths of the eighteenth century, Paul de Lamerie.

|

Figure 10: Paul de Lamerie, One of a Pair of Dishes and Detail (1746) |

|

|

Figure 11: Tobacco Box (1778–1830) |

Figure 12: Paul Storr, Wine Coaster (1815) |

When the men stayed in the dining room after dinner, they engaged not only in manly conversation, but also in prolonged drinking and smoking. Elegant dining room accessories included tobacco jars and boxes to keep the material fresh and at hand. Other accoutrements included objects associated with wine consumption. When alone in the room, the men served themselves from bottles of wine that were brought to the table. As the tablecloths had been removed at dessert, the rough bottoms of the hand-blown glass decanters could damage the table’s surface, and they were therefore placed in coasters.4 The men could get rather drunk and did not always hit their target when using a chamber pot in the room.

Figure 13: After Alphonse Roehn, “L’après-dinée des Anglais”

(Click here to see a larger version.)

With these habits in mind, let us examine a scene in Pride and Prejudice, when Elizabeth Bennet anxiously awaits Darcy in the drawing room at a dinner party at Longbourn:

the ladies had crowded round the table, where Miss Bennet was making tea, and Elizabeth pouring out the coffee, in so close a confederacy, that there was not a single vacancy near her, which would admit of a chair. And on the gentlemen's approaching, one of the girls moved closer to her than ever, and said, in a whisper, “The men shan't come and part us, I am determined. We want none of them; do we?” (377)

Austen is perhaps here hinting at the unpleasantness of the entrance of drunken men into the drawing room.5

Figure 14: Yellow Drawing Room, Harewood House

The drawing room was considered a feminine domain. It should, in Sheraton’s opinion, “concentrate the elegance of the whole house” (qtd. in Kinchin 13) and be a bright and lively space filled with mirrors and numerous lighting devices. The drawing room was the center of the feminine social activity of tea making, and the ritual was a fine display of feminine taste and hospitality. A woman of the house brewed and served the tea using ceramic and silver implements, including hot water kettles or urns, sugar containers and tongs, cream and milk jugs, teaspoons, and pots. When tea was first imported to England it was very expensive, and it was secured in locked boxes to which the female head of the household held the key; the habit endured even as tea became less costly during the eighteenth century.6 The scene in the Longbourn drawing room is interesting not only because it contains the solidarity-among-girls dialogue; it also explicitly details how coffee and tea would have been served. Jane makes the tea herself at the table, and Elizabeth is “pouring out the coffee” (PP 377). Servants prepared the coffee and set the pot on the table; a lady of the house then served the beverage.

Figure 15: Clockwise from left: Samuel Taylor, Pair of Tea Canisters and Sugar Bowl (1757); Unknown maker, Hot Water Urn (1770); Hester Bateman, Teapot and Stand (1785, 1783); Unknown makers, Sugar Tongs and Strainer Spoon (n.d.) |

Figure 16: John Swift, Coffeepot (1755) |

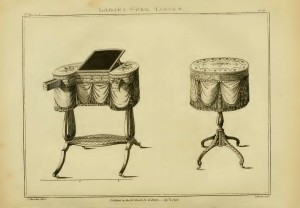

As a venue for socializing and as a place where unmarried women could showcase their talents to potential mates, the drawing room featured accessories having to do with sketching, needlework, and music-making. Austen fills her drawing rooms with feminine artistic accoutrements. Emma Woodhouse’s “‘inimitable figure-pieces’” decorate Mrs. Weston’s drawing room at Randalls (45). Lucy Steele draws her worktable near to make a filigree basket for a spoiled Middleton child. Shown here are two examples of worktables that feature framed-set bags to hold supplies for embroidery and other decorative work.7

Figure 17: Thomas Sheraton, “Ladies Work Tables” (1793) |

Figure 18: M. de Saint-Aubin, from The Art of the Embroiderer (1770) |

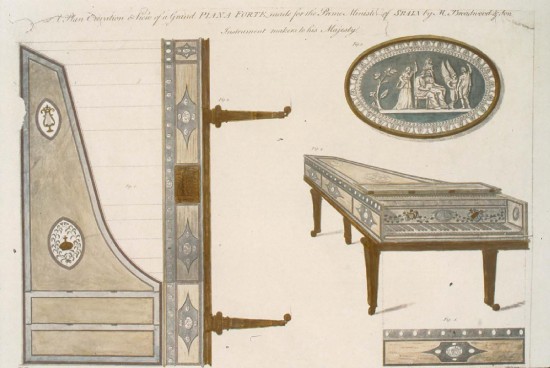

A lovely scene at the Parsonage at Mansfield Park describes two implements of female accomplishment: Mary Crawford, “[a] young woman, pretty, lively, with a harp as elegant as herself; and both placed near a window . . . was enough to catch any man's heart. . . . Mrs. Grant and her tambour frame were not without their use; it was all in harmony” (76). “Tambour” is the French word for drum, and the tambour frame was a hoop over which fine muslin or other fabric was stretched tightly to make it taut and ready for chain stitches made with a tiny hook. Instruments such as Mary Crawford’s harp and the new pianoforte in the Coles’ drawing room in Emma would have been located in a public room so that they could be easily accessible for entertaining guests.8 Pictured here is a pianoforte case designed by Thomas Sheraton for John Broadwood & Son, the firm from which Frank Churchill purchased Jane Fairfax’s instrument. Sarah R. Wakefield points out that “England’s social discourses at the turn of the nineteenth century clearly discouraged gentlemen from dabbling in music”; playing music was appropriate for women and professional musicians only.

Figure 19: Thomas Sheraton, “Plan Elevation & View of a Grand PIANA FORTE” (1796)

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Although Northanger Abbey boasts two drawing rooms, there is no mention of an instrument in that or any other room in the house, nor talk of Eleanor Tilney’s being able to display her accomplishments in any way. Moreover, her role as woman of the house is constantly being usurped by her father, General Tilney. After she has told him that she was just beginning to invite Catherine Morland to the Abbey, he says, “‘Well, proceed by all means. I know how much your heart is in it,’” and yet in his next breath he asks Catherine himself (141). He also gives Eleanor “a strict charge against taking her friend round the Abbey” without him (186).

Figure 20: After Augusts Charles Pugin, Library at Cassiobury Park (1816)

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Figure 21: East Bedroom, Harewood House

In the numerous descriptions of the interior of the Abbey, we hear of the General’s decorating efforts in the traditionally masculine rooms, which are described in terms of importance and dignity: a magnificent library, “exhibiting a collection of books, on which an humble man might have looked with pride” (188), and the “dining-parlour,” “a noble room . . . fitted up in a style of luxury and expense” (170). His efforts of major refurbishment, traditionally the purview of the man of the house, include “most completely and handsomely fit[ting] up” three large bedrooms and their dressing rooms, undertaken in the last five years (190). He has installed new “stoves and hot closets” (189) for the spacious kitchen. Vickery has commented that although this room was a site of “female expertise,” “richer male households could take quite an interest in the stove and major kitchen fittings” (267).

Figure 22: Rundlet-May House Kitchen (1807) |

Figure 23: Plan of Rumford Fireplace |

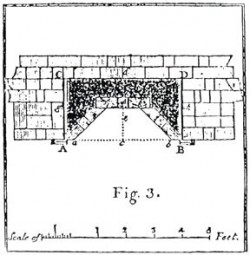

The General’s masculine hand can also be seen in the improvements to household spaces and the acquisition of objects that are usually the domain of women. For instance, in the common drawing room, a space in which Sheraton indicates there should be nothing of a scientific bent, he has installed the innovation of a Rumford; the specifications of this heat-saving fireplace had recently been published by its inventor Benjamin Thompson (also known as Count Rumford) in 1796. The General brags about the cost and elegance of the larger drawing room, which is described in the same type of masculine language as the dining parlor; it is “used only with company of consequence” and is “magnificent both in size and furniture” (187). Furthermore, the fact that the General is so familiar with all the adornments of the room, shown by his “examination of every well-known ornament” (188), suggests that he procured them and that they were not the choice of his wife or daughter. He also probably purchased the ornaments “of the prettiest English china” (165) over the Rumford; this is most likely a garniture, a matching set of vases that “garnished” a chimney mantel and was a category of china that normally would have been chosen by a woman. He is proud to have selected a breakfast set, claiming masculine allegiance to his county of Staffordshire, a famous center of ceramic production. As we have seen with Mrs. Dashwood’s example, however, breakfast sets are associated with women, but it seems unlikely that the General would have sought Eleanor’s opinion on this purchase.9 Very tellingly, he refuses to let his wife symbolically preside over a drawing room by not hanging her portrait there as was planned; “for some time it had no place” (185) and was after her death rescued by Eleanor to hang in her own bedroom. These domestic choices made by the husband instead of by the wife are perhaps examples of Mrs. Tilney, as Henry comments, “‘often hav[ing] had much to bear’” (203).

Figure 24: Wedgwood and Bentley, Three-piece “Hamilton” Vases (ca. 1770–1780)

Figure 25: Pierre-Charles Baquoy, “Mise de Jeune Homme”

(Click here to see a larger version.)

The narrator tells us that the General is “accustomed on every ordinary occasion to give the law in his family” (257); he involves himself in household matters great and small, important and frivolous, substantial and delicate, turning everything into a masculine concern. A subtle example of General Tilney’s “parental tyranny” (261) is his spreading out his greatcoat in the curricle in which he rides with his son Henry, therefore physically and psychologically taking up more than his share of space. The greatcoat is important to our discussion because it is an excellent example of male clothing of the Regency period that, in contrast to female clothing of that era, echoes the same concepts of seriousness, substantiality, and dignity that characterize masculine rooms and furniture.

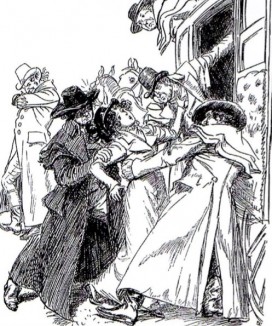

The greatcoat was a long wool overcoat, heavy and warm, which made it practical to wear by carriage drivers, with whom it was particularly associated. By 1800, however, they were being worn as stylish town wear by gentlemen as they drove their own carriages (Waugh 54). The warmth that a greatcoat provides makes it a good option for two of Austen’s sickly characters: Mr. Woodhouse’s is fetched by Mr. Knightley before his winter walk, and “‘poor Arthur’” (Later Manuscripts 186–87) is helped into his by his sister Diana Parker before he goes to take his lodgings upon his arrival in Sanditon. Greatcoats could have one or multiple capes on the shoulders for extra warmth and protection, with an added advantage that they “could flap dramatically while in motion” (Nigro). The dramatic, and even dangerous, aspect of the garment is alluded to in Northanger Abbey in explaining Captain Tilney’s lack of interest in Catherine Morland: “He cannot be the instigator of the three villains in horsemen’s great coats, by whom she will hereafter be forced into a travelling-chaise and four, which will drive off with incredible speed” (133). Stephen Derry has pointed out that here the greatcoat symbolizes the sexual threat of male power (50). The reasons for Mr. Allen’s refusal to ever “‘walk out’” (NA 81) in one are not known—perhaps he found them too fashionable, too cumbersome, or too dramatic.

Figure 26: After Victor Auger, “Mr. Garrick, introducteur de modes” (1813) |

Figure 27: Hugh Thomson, “The three villains in horsemen’s greatcoats” (1901–1903) |

Figure 28: H. M. Brock, “Henry drove so well” (1907)

Henry Tilney’s greatcoats are mentioned three times. During a tour of the Abbey with General Tilney, Catherine sees a “a dark little room, owning Henry’s authority, and strewed with his litter of books, guns, and great coats” (188), an excellent list of masculine gendered objects. He is wearing one when he leaves to prepare for a dinner at his own house, Woodston. Earlier in the novel, he wears one during their trip to the Abbey, and Catherine finds him quite dashing: “And then his hat sat so well, and the innumerable capes of his great coat looked so becomingly important!” (160).

The fact that this ponderous coat, with only capes for decoration, was a fashionable garment that could add to a man’s charms speaks to the overall lack of embellishment in men’s clothing of the time. The psychologist J. C. Flügel coined the phrase “The Great Masculine Renunciation” to describe how at the end of the eighteenth century “men gave up their right to all the brighter, gayer, more elaborate, and more varied forms of ornamentation, leaving these entirely to the use of women, and thereby making their own tailoring the most austere and ascetic of the arts” (110–11). Men’s ensembles of the early and middle Georgian era had been made in brightly colored, lavish, and hard-to-care-for fabrics like satins and velvets. They featured elaborate embroidery and trim, and they were widely cut.10 In the late Georgian or Regency period, men aimed for a simpler way of dressing that was influenced by the practical garb of gentlemen while on their estates in the country and was inspired by ancient sculptures of nude athletes that displayed every line of a man’s contours. A high-waisted and narrow silhouette was created by short-bodied waistcoats, leg-hugging breeches or pantaloons, and coats with tails instead of full skirts. These garments were made in practical textiles such as unadorned wool, cotton, linen, and buckskin, all in subdued colors.

Figure 29: Pompeo Batoni, George Lucy (1758) |

Figure 30: William Owen, Portrait of a Man (c. 1815) |

Figure 31: Unknown British maker, Robe à la Française (1740s) |

Figure 32: Portrait of a Lady from a drawing by Adam Buck (1803) |

Like male clothing, female dress of the late Georgian period was simplified and inspired by antiquity, but practicality was not required by women of this era. Gowns were no longer made of huge amounts of luxurious and decorated silk shown off in wide silhouettes created by petticoats, padding, and hoops. The neoclassical gown had a column-shaped skirt worn over less-substantial underpinnings than before, and a softly rounded neckline and short sleeves exposed large areas of flesh, so women dressed in these gowns could look almost nude to people of older generations. Women continued to wear silk, although in less elaborate designs, and they more often chose lightweight white cotton muslin for day and evening wear. This could be decorated with embroidered patterns, which were often white on white, or even when they were in color, were much less elaborately done than they had been in the earlier Georgian era.11 Although the basic silhouette of the neoclassical gown was simple, it could be embellished with various trimmings, which in the opinion of the antiquarian and designer Thomas Hope could get out of hand. He railed against “paltry and insignificant gew-gaws and trimmings, that can only hold together through means of pins, sowings, and other eye-rending contrivances, unknown in ancient dresses; through which the breadth and simplicity of modern female attire is destroyed and frittered away” (Hope 12).12

Figure 33: The Fashions of the Day—or Time Past and Time Present: The Year (1740) a Lady’s Full Dress of Bombazeen—The Year (1808) Lady’s Undress of Bum-be-seen (c. 1808)

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Muslin is a thin and delicate material, and it is only relatively less expensive and easier to care for than silk, and so it was not as practical as the textiles used in male clothing of the time.13 As Henry Tilney remarks of Catherine Morland’s muslin gown in Northanger Abbey, “‘I do not think it will wash well; I am afraid it will fray’” (21). So, whereas in the early and middle Georgian era both men and women wore elaborate clothes made from impractical materials, during the Regency years their clothing began to exhibit several male/female binaries that fashion scholar Chloe Chapin has observed throughout the nineteenth century: durable vs. flimsy, plain vs. embellished, covered vs. exposed, and practical vs. impractical. Light-colored and delicate fabrics are more expensive and easier to damage, and before the end of the eighteenth century they would have signaled wealth, with practical clothing being worn by the working classes. With the change in male clothing of this era, the “visible impracticality of dress . . . shifted from signaling status to marking femininity” (Chapin).

Delicate and insubstantial muslin fabric was used for male shirts and cravats, the latter of which Henry Tilney says he buys for himself. The fabric’s delicacy gave it a feminine association, however, so much so that “muslin” was slang for “girl.” Phrases using the word had sexual implications, such as “a bit of muslin” denoting “a woman, a girl,” and “a bit of muslin on the sly” referring to illicit sexual acts (Eric Partridge qtd. in Heydt-Stevenson 87). In multiple instances, Austen likens the fragility of muslin and gowns to the vulnerability of a woman’s reputation. Lydia Bennet’s letter alerting Mrs. Forster to her elopement with Wickham mentions “‘a great slit in [her] worked muslin gown’” (PP 321). Fanny Price warns Maria Bertram that she will tear her gown if she slips through a locked gate at Sotherton to be alone with Henry Crawford. When Mr. Allen tells Catherine Morland that it is not appropriate for young women to ride in open carriages with men, his wife adds that such activity could soil a “clean gown” (NA 105).14

Mrs. Allen is concerned with the vulnerability of muslin gowns in less morally dangerous circumstances, as well. At the crowded assembly she interrupts the first conversation between Henry Tilney and Catherine Morland to declare that she is afraid that a pin has torn a hole in her favorite gown. In the ensuing discussion we learn that Henry understands muslins “‘[p]articularly well’” and signals that he is able to get into the mindset of a woman: he would have guessed the cost of Mrs. Allen’s muslin correctly, and his sister Eleanor “‘has often trusted [him] in the choice of a gown’” (20). Although he does not think Catherine’s garment will wash well, he is able to see how the material can be used for practical purposes, saying, “‘muslin always turns to some account or other; Miss Morland will get enough out of it for a handkerchief, or a cap, or a cloak.—Muslin can never be said to be wasted’” (21). He thus hints at the fact that although muslin and women can be seen as fragile, he understands the worth of both the material and the gender.

Much has been written on the degree to which Henry is feminized by his knowledge of muslin, as well as by the softening of his voice to imitate an affected dandy as he asks Catherine about her initial reaction to Bath (Fuller 92), and by his enjoyment of novels.15 Contrastingly, Henry often adopts the type of overtly male ponderous importance that is demonstrated daily by his father; Henry’s criticism of Catherine’s use of the word “nice” (NA 109) and his opinion that “‘a taste for flowers is always desirable in your sex’” (178) are two examples. This type of talk is done in jest, however, for as Eleanor says, “‘I do assure you that he must be entirely misunderstood, if he can ever appear to say an unjust thing of any woman at all, or an unkind one of me’” (115).

Eleanor’s trust in the ability of Henry to choose her garments is a sign of his respect and love for her, and his appreciation of both the masculine greatcoat and feminine muslin hints at the equality between men and women that he espouses in the very first conversation he has with Catherine: “‘In every power, of which taste is the foundation, excellence is pretty fairly divided between the sexes’” (20). General Tilney, too, deals with both the masculine and the feminine, shown in his decorating efforts in traditionally male and female rooms, as well as his acquisition of domestic technology and decorative objects. Due to his tyrannical ways, however, he denies female authority and takes over every single aspect of the domestic sphere. We have seen that Robert Ferrars’s masculine authority cannot be lessened by his obsession with a toothpick case, and the General’s dominance over things both feminine and masculine speaks to the domestic tyranny that nullifies Eleanor’s role as female head of the household. In Northanger Abbey and throughout her novels, Austen’s representations of greatcoats and muslin gowns, as well as drawing room and dining parlor interactions and furnishings, address and sometimes challenge her era’s ideas about masculine importance and female delicacy.

NOTES

1In this essay I will be using the gendered terms of woman, man, feminine, and masculine to refer to socially constructed roles as they were understood in Austen’s time. I will not be addressing sexual orientation, nor using the greater number of gender fluid terms to which we have access today.

2See the excellent “A Sex in Things,” chapter 10 of Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England, as well as Vickery’s introduction, with John Styles, to Gender, Taste, and Material Culture in Britain and North America, 1700–1830.

3The bachelor Frank Churchill is a duplicitous shopper, proposing the purchase of gloves at Ford’s to distract Emma from asking him about Jane Fairfax and later anonymously buying a pianoforte for Jane.

4These had grooved wooden interior bases to bear the coarse bottles and keep the moist surfaces from adhering; the undersides were lined with felt to protect the table.

5Another example occurs in Emma after the Christmas dinner at Randalls, when Mr. Elton forcibly seats himself between Mrs. Weston and Emma. His drunkenness becomes more apparent during the carriage ride when he makes his unwelcome marriage proposal.

6Geoffrey Wills has pointed out that the fact that these tea chests were small and “easily portable, locked or otherwise, would point to the likelihood that security was little more than a pretense” (142); someone could make off with the box itself.

7The worktable on the left, as Sheraton says, is “intended to afford conveniences for writing, by having a part of the top hinged in front to rise up, and drapery to hide the work-bag” (Appendix: “An Accompaniment to the Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book” 49). In contrast, men’s desks never combined a writing surface with a place to store embroidery materials.

8The Musgrove sisters have added both a harp and a pianoforte to the “the old-fashioned square parlour” (P 43) of the Great House at Uppercross. See Zohn for a discussion of the significance of these additions.

9The general’s behavior is in contrast to that of Edward Austen Knight, who chose the family dining set with the help of his daughter Fanny.

10Mr. Rushworth seems to miss the luxurious fabrics of the earlier era, as he is very excited that his costumes for the play at Mansfield Park involve “‘a blue dress, and a pink satin cloak . . . [and] another fine fancy suit by way of a shooting dress’” (MP 163). Esra Melikoğlu cites this as one reason that he can be labelled a “fop,” a man who dresses for show, and in his passion for clothing and affected manners can be seen as feminine.

11Catherine Morland lies awake trying to decide between her gowns with two different patterns. One was her tamboured gown, the technique of which we have spoken above; twining or vine-like patterns worked best with this technique. The other gown under consideration was her spotted one; today we might call this polka dots or dotted swiss. Elsewhere in the novel we learn that she also has a sprigged muslin gown (decorated with a design of sprigs of leaves or flowers) with blue trimmings.

12For an in-depth study of Hope and neoclassical dress, see Van Keuren and Zohn.

13The fragility and vulnerability of the female gown could sometimes be offset by masculine outerwear like the riding habit, or redingote. Whereas by Austen’s era female dressmakers produced women’s clothing, these riding habits were still tailored by men and were constructed of wool or other strong fabrics (Hern). Another type of women’s outerwear, the spencer, was also an adaptation of men’s clothing. This waist-length jacket was named after George, 2nd Earl of Spencer, who is said to have started the fashion for short jackets without tails in the 1790s (“Spencer Jacket”).

14For a full discussion of the sexual connotations of gowns in Austen’s novels, see Fuller.

15A dandy paid particular attention to his clothes and appearance, but without the showiness of the fop. Dandies were also seen as partially feminine due to this particularity (see “Fops”). For a discussion of Henry as a feminized hero, see Eddleman; Sarah Eason and Edward Kozaczka discuss Henry as queer due to his ambiguous gender performances. These three articles include the viewpoints of other scholars such as Claudia Johnson and Judith Wylie. Peter W. Graham calls Henry a beta male, citing his habitually cooperative and laidback behaviors.