In March 2022, for the first time since the Covid-19 pandemic, I visited Godmersham Park to lead a group of graduate students studying Jane Austen on a tour of the Kent house and estate inherited by her brother Edward from Thomas and Catherine Knight. Our usual route for such visits starts from the carriage circle in front of the House and concludes at St. Lawrence Church. This year, for reasons I cannot remember, we began at the Church, where we made for the exterior wall of the northwest buttress of the chancel to visit the stone memorial for Susannah Sackree, nurse to the eleven children of Edward Austen (Knight) and Elizabeth Austen (née Bridges). When I first visited Godmersham Park over ten years ago, the memorial clearly displayed Sackree’s name at its head—although without the “h” that usually appears at the end of her first name in the genealogical record—while the markings of the words beneath her name were more faintly discernible.1 By March 2022, I was saddened to see that the lettering had weathered to near illegibility.

Memorial to Susannah Sackree.

Mercifully, the inscription has been preserved in the form of an illuminated scroll displayed within the church. Created by Hazel Jones following a 1993 donation from JASNA, the scroll documents that Sackree was:

The faithful servant and friend for nearly 60 years of Edward Knight Esquire of Godmersham Park and the beloved nurse of all his children. She died deeply lamented on the 2nd March A.D. 1851 in the ninetieth year of her age.

Beneath this text are the words from Psalm 37 that Sackree requested to have on her tombstone, followed by a few lines of verse.

My dearest friends I leave behind,

Who were to me so good and kind.

The Lord I hope will all them bless

And my poor soul will be at rest.2

I had seen the scroll at least a dozen times before this visit and have witnessed students being visibly moved by the memorial and its demonstration of Edward Knight’s affection for his “faithful servant and friend.” Yet rather than occasion poignant feelings of remembrance and friendship, on this occasion the memorial produced only profound discomfort at the thought that Susannah Sackree was receding from memory. Moreover, I realized that she had long been remote to us.

Image reproduced courtesy of Jane Austen’s House, Chawton.

With few exceptions, servants are notoriously spectral figures in Jane Austen’s fiction and its surrounding scholarship.3 Likewise, in histories of Georgian Britain, even remarkably faithful and long-lived servants like Susannah Sackree are often little more than footnotes to the main political, economic, or artistic narrative.4 The marginalization of the women and men who serviced not only individual households but also the nation is sometimes justified on the grounds of paucity of evidence, and Sackree’s life is certainly not overburdened with source material. A few artefacts pertaining to her have survived, including two images. The first—a silhouette of Sackree at work knitting stockings, possibly for one of her charges—was donated to Jane Austen’s House in 1972 by Mrs. B. M. J. Causland, great-granddaughter of Fanny Knatchbull (née Austen, later Knight). The second, an unsigned and undated portrait, is also in the collections of Jane Austen’s House. Together, these images go some way to making Sackree visible to us, but it is still hard to see the woman behind the artists’ impressions.

Indeed, the memorial is the most substantive evidence for her biography, even if it is one that positions her not in relation to her biological family but to the Knights, by whom she was employed from the birth of Edward and Elizabeth’s first child, Fanny. Sackree was still living with and working for the Knights fifty-eight years later. During that time, she served as the nurse of the remaining Knight siblings, and survived both Elizabeth Austen, in 1808, and the death of the Knights’ third son, Henry, in 1843. Prompted by the weathering of the Godmersham memorial, this essay seeks to restore as full a life of Susannah Sackree as is currently possible. It seeks to add texture to the glimpses of Sackree captured by surviving material artefacts and standard biographical information captured in histories of the Austen and Knight families, as well as to recover traces of her life, work, and agency through four types of evidence: the 1841 census; letters and diaries; texts, including Jane Austen’s novels; and Sackree’s will.

Piece 1: The census

Susannah Sackree died just weeks before the 1851 census was taken. She does, however, feature prominently in the 1841 return, where her name appears at the top of the list of the Godmersham Park servants and immediately beneath the entries for Edward Knight senior; Sackree’s former charges Henry, Brook, and Marianne Knight; Edward’s sister-in-law Louisa Bridges; and Edward’s granddaughters Elizabeth and Marianne Rice. Little further information is divulged by this coy document beyond the fact that Sackree was born in Kent. Had she lived until the 1851 census date, when entries became more detailed, we might have learned from which town or village in the county she heralded. The return gives away little about her occupation, which is denoted simply by “f. s.,” an abbreviation that indicates that Sackree was one of twelve female servants at Godmersham Park at the time. This was in addition to nine male servants, as well as several male and female agricultural laborers and their families who lived on the estate. Only from the 1851 census onwards were service roles more precisely delineated. In that later document, we learn that Elizabeth Blacklocks (whose name appears immediately below Sackree’s in the 1841 census) was the Park’s housekeeper. Blacklocks likely took over the role following Sackree herself. Lord Brabourne documents that in 1822 “Mrs Sayce,” Fanny Knight’s lady’s maid and Sackree’s niece, left Godmersham to marry a German husband, after which Sackree “succeeded her [Sayce] as housekeeper” (2: 128).

Brabourne’s phrasing suggests a causal relationship between these events, implying that Sackree succeeded Sayce, who in turn succeeded Mrs. Driver and, before her, Mrs. Salkeld, the Godmersham housekeeper known to Jane Austen. Lord Brabourne’s unacknowledged source for this information is his mother’s pocket diary for 1822, in which Fanny Knatchbull marked both the marriage of her former lady’s maid, Sayce, and Sackree’s new role as housekeeper in her yearly digest of familial and national news. She does not, however, connect the events in the way that her son does; she merely records that both events occurred in the same year. How actively or not Sackree was working in 1841 (at around eighty years of age) is undocumented, although as Tessa Boase notes, many housekeepers of the time worked up until their deaths (41, 93). It is worth noting, however, that in 1841, Sackree was more than three decades the senior of the next oldest Park servant, Mary Goldsmith (around 45), and more than six decades older than its youngest, Henrietta Cross (around 15).5 Indeed, Sackree was the oldest resident of the entire household, including her employer and friend, Edward Knight senior.

Piece 2: Letters and diaries

Lord Brabourne’s aforementioned discussion of Sackree is at pains to document the regard in which this “excellent woman” and “great favourite” of the Knight family was held (126). He recalls a funny, if admonitory, anecdote that Sackree used to tell the Knight children and grandchildren and refers to her nickname, “Caky” (or Cakey), a term of endearment frequently prefaced by “Dear” or “Dearest” in Fanny Knight’s diaries and that apparently stuck after one of her charges struggled to pronounce her surname in toddlerhood. Brabourne further notes that Sackree is mentioned frequently in Jane Austen’s letters from Godmersham in relation to her care of the Knight children (127). Indeed, references to Sackree’s feelings are lightly sprinkled throughout Jane Austen’s surviving correspondence. In a letter to Cassandra on 30 January 1809, for instance, Austen contemplates how “brokenhearted” Sackree must have felt when, in January 1809, she travelled to Essex with the young Lizzy and Marianne Austen to leave them at a boarding school for a few months while Fanny sought a new governess in the aftermath of her mother’s death. Sackree’s health is also a recurrent topic in the Austen and Knight family’s correspondence, in which her intermittent bouts of fever, stomach-ache, and other complaints are documented with palpable concern. The impression that Sackree was considered part of the extended Austen-Knight household-family is deepened by nods in Austen’s letters to Sackree’s newsy correspondence about the Knight children and to occasions when Austen visited Godmersham and read aloud letters from Chawton to the nursemaid.

Yet for all their mutual regard, Sackree’s relationship with Austen was necessarily more complex than with the Knights, who employed her. In a well-known letter dated 24 August 1805, for instance, Austen expresses embarrassment over her inability to tip Sackree more than 10 shillings after an extended visit, having “sunk in poverty”—a moment that simultaneously underscores Austen’s social privilege and her financial precarity. Less well known, although arguably more arresting, is an event that Austen communicated to Cassandra at Sackree’s request. In a letter dated 15–17 June 1808, Austen notes that after accompanying William Knight to Eltham, Sackree and she travelled on 4 June to St. James’s Palace where they “saw the ladies go to Court.” Austen adds one further, revealing detail before moving on to other matters: “Sackree had the advantage indeed of me in being in the Palace.” Sackree’s admittance to St. James’s, while her employer’s sister was required to wait outside, was likely due to the servant’s connection to Sophia Fielding, a relation by marriage to Sir Brook Bridges of Goodnestone (Elizabeth Austen’s father) and the daughter of Lady Charlotte Finch, governess to the children of George III.6 Both of these letters gesture to the far from straightforward set of financial and status markers that mediated the relationship between Austen and Sackree and highlight the different kinds of dependencies that shaped their lives and social interactions with each other and with the Knight family.

After Austen’s death in 1817, we must turn to Fanny Knight to pursue the epistolary trail for Sackree’s biography. Fanny’s earliest references to Cakey are not always informative and usually confined either to acknowledgements that the nursemaid wished to be remembered to Fanny’s correspondent or to vague remarks about her health. Only two letters written by Sackree herself are known to have survived. Written in a scrawling and imperfectly spelled and punctuated hand, these were addressed to the former Godmersham governess, Miss Chapman. Both letters were written in the days following Elizabeth Austen’s death in October 1808. Sent “with speed” to an anxious Miss Chapman, who was awaiting further news, they provide an altogether more detailed and moving account of Elizabeth’s decline than the better-known account penned by Jane Austen. Sackree writes with evident pain about the “shocking advent” of Elizabeth’s unexpected death after a birth that was as “good” and “easy” as any of those she had had of her “dear children.” Sackree notes that a few days after the birth Elizabeth sat down in good spirits to eat a “heavy” dinner of chicken (“Chicking”), after which she felt sick and felt went for a “ly down.” Less than half an hour later, with no forewarning, she was dead. Sackree proceeds to capture the effects of Elizabeth’s death on her “dear Master,” Edward, his young children, and Cassandra Austen, who was at Godmersham at the time and who proved “a great consolation” to the entire household, including Sackree herself. Sackree does not allow herself much space in the letters to elaborate her feelings, but the sense that she is utterly bereft for the loss of a good woman who meant so much not only to her husband and children but to her servant is nonetheless painfully evident. Sackree concludes with a plea that she hopes “never [to] see such another time of misery” in the rest of her days.

The overwhelming grief that Sackree experienced was endured by others in her life, however, not least by the woman whose birth occasioned her employment with the Knights in the first place.7 In late February 1851, fifty-eight-year-old Fanny Knatchbull wrote with increasing helplessness in her diary of the deteriorating health of her former nurse. On a visit to Godmersham on 23 February 1851, she noted that “Poor dearest Cakey was very ill all day,” so ill that Fanny felt unable to leave her. Over the next few days, Sackree became greatly distressed and weaker by the hour. When Fanny “finally” left her on 28 February 1851, she must have known that she would not see Sackree again. Just a few days later, Fanny’s diary entry for 2 March 1851 eschews the usual format she adopted: a note on the weather before an abbreviated account of the day’s events. Instead, it reads: “Our dear invaluable & wise Susanna Sackree (Cakey) expired at ½ past 5, this morning in her 90th year. A superior and excellent woman! 58 years & ¼ in the family.” Six days later, on 8 March 1851, she ends her entry with Sackree’s burial: “My darling Cakey was buried in Godmersham Churchyard, close to the family vault.” Given her age and illness, Sackree’s death could not have been a shock to the Knights. But as at the death of Fanny’s mother over forty years earlier, the sense of unbearable sadness and of a household irrevocably changing is palpable in Fanny’s words about a woman she had known and loved from infancy.

Piece 3: Literature

But what of Sackree’s work? In the absence of concrete information in the historical record, literature can help to fill some of the gaps. Sackree’s first duties at Godmersham, in and over the nursery, would have been multiple and diverse. According to Samuel and Sarah Adams’s Complete Servant (1825), this role was of paramount significance within and beyond the household: “As the hopes of families, and the comfort and happiness of parents are confided to the charge of females who superintend nurseries of children, no duties are more important, and none require more incessant and unremitting care and anxiety” (254). The Adams’s account proceeds to elaborate the Head Nurse’s specific tasks: being vigilant about approaching illness; tending to and curing ailments; washing the children carefully; ensuring that their clothes fit well and that they take sufficient exercise; taking care that they had enough sleep; and maintaining constant vigilance against household hazards (254). The role also involved the management of younger nursery-nurses. This summary of duties is necessarily selective—it extends to nine pages in the Complete Servant. Suffice it to say that the role required not only a singular capacity for “care and anxiety” but also considerable stamina. As the Adamses were at pains to point out, the Head Nurse’s activities were “incessant” but had to be undertaken with a uniformly “lively and cheerful” disposition (254).

It is unclear precisely how Sackree’s duties evolved once the Knight siblings attended school and, in turn, reached adulthood. Given that Brook, the youngest of the Knight children, was seventeen when Sackree was appointed housekeeper, we might assume that in the late 1810s, Sackree’s position was not dissimilar to that of Sarah, nursemaid to the Musgroves in Persuasion (1818), and for whom Charles sends after Louisa’s fall at Lyme. Henrietta wishes to care for her sister herself, but instead “Charles conveyed back a far more useful person in the old nursery-maid of the family, one who having brought up all the children, and seen the very last, the lingering and long-petted master Harry, sent to school after his brothers, was now living in her deserted nursery to mend stockings, and dress all the blains and bruises” (132).

In 1822, however, as the new housekeeper of Godmersham, Sackree would have had little time to mend stockings now that her responsibilities included managing the Park’s servants as well as household furniture, linen, groceries; ensuring the tasteful presentation of table and home; and making “pickles, preserves, . . . pastry” (Adams 64). Like the enigmatic yet pivotal and “intelligent” Mrs. Reynolds in Pride and Prejudice (1813) (277), Sackree’s unofficial responsibilities at this time likely also included curation of the family’s reputation, given her intimate knowledge of the family and of its children since infancy.

Piece 4: The will of Susannah Sackree

So far, this essay has primarily focused on how Sackree was perceived by the family who employed her. But it is important to acknowledge that she actively sought to shape how others perceived and remembered her. Sackree’s will is dated 25 March 1847, with a codicil dated 3 June 1850, less than a year before her death. Like all the pieces of evidence upon which this essay draws, Sackree’s will primarily identifies her in relation to the Knights. Edward Knight senior and junior were her executors, and she charged them with using money she held in “public funds” and in the “Savings Bank Ashford” to pay off her debts and administer her estate. George Knight and Fanny witnessed the document, while their unmarried sister, Marianne, was named as the beneficiary of Sackree’s “clothes, books and trinkets” as well as any financial residue left after her debts and familial bequests were issued.

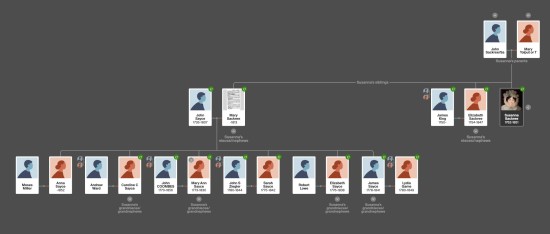

Sackree Family Tree. (Click here to see a larger version.)8

These bequests—especially to unmarried or widowed women in her family—provide concrete links to Sackree’s biological, rather than household, family. And it is through these details that we can partially sidestep the challenges of variant spellings (Sacry, Sakry, Sachary) that thwart the genealogist and begin to construct a family tree for Sackree via a group of female relatives who are commonly referenced in her will in relation to their husbands: “Anna Widow of Moses Miller,” “Susannah Wife of Ridgen Major” (a noted mariner), “the Widow of James Sayce,” and so on. Identifying these women directs us to parish records that allow us to move up one generation of the family tree to identify Sackree’s two sisters. Her oldest sister, Mary Sayce (born c.1751 as Mary Sackree), was the second wife of John Sayce, an engraver whom she married in Camberwell, London, in 1772. The couple had at least five daughters and a son, including Anna (aforementioned wife of Moses Miller) and Sarah Sayce, whom Lord Brabourne identified as the lady’s maid of his mother, Fanny Knight. Mary Sayce (née Sackree) died in November 1813 and was buried on 8 December 1813 in Southwark. She was outlived by her husband and seems to have left no further biographical trace. More can be reconstructed about the life of Mary and Susannah’s middle sister, Elizabeth. Born in 1754, Elizabeth lived until the formidable age of 93 and died in Ramsgate in 1847. Elizabeth married James King on 14 July 1776 in Folkestone, where the couple’s daughter, Susannah (aforementioned wife of Rigden Major), was born. Identifying Sackree’s sisters forces the conclusion that she was most likely the youngest of the three daughters of John Sackree and Mary Talbot (or Toplut) and baptized in Folkestone in 1762. We know from Sayce’s appointment as lady’s maid at Godmersham and a reference in Jane Austen’s letter to Sackree’s sister in London (presumably Mary) that Sackree maintained contact with her family throughout her life. The bequests in her will confirm her care for, and financial commitment to, her sisters and their children, particularly to those who were single like herself.

The will is still more important because of a detail omitted from existing accounts of Sackree’s life and from the memorial itself. While the position of the stone on the exterior wall of St. Lawrence Church, Godmersham, undoubtedly speaks to the Knight family’s affection for their “faithful servant,” the will clarifies that it was not the Knights but Sackree who commissioned the memorial and provided the text for the inscription. The document opens by stating that, once her debts, testamentary, and funeral expenses were paid, Edward Knight senior and junior were to use her estate for “the expense of a stone with a suitable inscription which I desire to be erected in my memory in the Godmersham Church Yard all within the space of 3 months after my death.” A little of Sackree’s agency (of Sackree herself) is eroded every time we tell the story of the memorial and neglect to mention that it was not Edward who generously commemorated her life of service, but Sackree herself. Sackree willed to be remembered. Readers may be pleased to learn that plans are being made to restore the Sackree memorial.

NOTES

1Throughout this essay, I will follow the convention of referring to Sackree by her surname only as the Austen and Knight families did.

2 An additional transcription of the tombstone of unknown date and hand can be found on a loose leaf inserted into Sackree’s own copy of The Book of Common Prayer (London: John Reeves, 1812), which is now held by Jane Austen’s House.

3Notable exceptions include essays and articles by Dredge, Sales, Terry, Veisz, and Walshe.

4Carolyn Steedman’s excellent Labours Lost is a recent exception.

5Ages were routinely rounded up or down to the nearest five years in the 1841 census, so precise ages need external verification.

6The precise nature of this connection, which is noted by Le Faye (Jane Austen’s Letters 400 n17), is difficult to determine with certainty. Sackree knew Mrs. Fielding through her relative Elizabeth Bridges. This acquaintance between Sackree and Fielding might have begun after Sackree’s employment at Godmersham, but it is tempting to speculate that, prior to taking up that position, Sackree might have worked at Goodnestone for the Bridges, which would mean that this acquaintance might have been of longer duration.

7I have not been able to confirm Sackree’s previous employment, but it is possible that she worked for Edward and Elizabeth Austen after working at Goodnestone.

8The family tree I have created for Sackree is publicly available here: https://www.ancestry.co.uk/family-tree/tree/182455867/family?cfpid=112387230749.