This is an account of two experimental Austen seminars that took place in the spring of 2022, one at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School in Jackson, Mississippi, the other in Oxford at the University of Mississippi. We explain how these two groups of students came together to hold the first-ever Jane Austen conference at the university and how this collaboration was an extension of our efforts to transform the literature classroom. For us, the instructors, these experiences proved energizing. Using authentic forms of assessment, each of us encouraged students to use literature in ways that mattered most to them. The resulting student work was inspiring, leaving us optimistic about the future of Austen studies and about the continuing vitality of Austen in a changing media landscape.

Gen Z, end times, and the Austen seminar

Carolyn Brown:

In 2018, the English Department at the private high school where I was teaching in Jackson, Mississippi, approved a radical curriculum change in the English Department: to offer semester-long classes senior year that resembled literature classes in college. Faculty would teach their “passions” rather than the traditional AP Literature class or regular English 12 that is taken over the entire senior year. My contribution to the new curriculum was the class “Timeless Jane Austen,” and the first challenge I encountered as I created the proposal for the class was determining what texts to teach. As a biographer myself, I decided to begin with a short biography of Austen, Carol Shields’s Jane Austen: A Life, followed by two novels, one written during the first half of Austen’s career, Pride and Prejudice, and the second written at the end, Persuasion. Both novels serve as a palimpsest of the author’s life and are interesting to compare as texts.1 In addition to assigning the biography and two novels, I would expand upon each topic with scholarly articles, videos, and guest speakers. I have always believed that hearing from voices other than mine, whether through reading literary criticism, watching videos, or hearing speakers live or over Zoom, helps to keep students more engaged with the material and provides a fuller understanding of the text.

At the end of each unit, I assigned the obligatory paper and gave an exam. When the class went online in spring 2020, my colleagues and I faced a new reality. In every faculty meeting I attended during the pandemic, there was discussion about the increase of cheating and plagiarism on tests and papers. To my knowledge I had not personally been faced with it, but I did not want to be, and I quickly realized that I would need to diversify my assignments and modes of assessment. Clearly, my students were more proficient in the ways of digital media than I. Why not embrace it? The world was changing; in the future they would be creating PowerPoints, communicating over social media platforms, and presenting online. Skills like these would be much more valuable to their futures than writing a traditional research paper or taking a multiple-choice exam. I needed to do something new.

Jason Solinger:

The inspiration for one of the most joyful literature classes I’ve ever taught came from two places. One was pandemic-era fatigue. I was tired of reading boring essays. When a world event makes you question the point of everything, the last thing you want to be doing is assigning essays to people who don’t see the point of writing them. Under the best of circumstances, teaching academic writing leads to existential questions about purpose and aims. “Why do we need to write this essay?” is what a class of mutinous students might shout in a teacher’s nightmare. It’s also the question every writer must answer before beginning. New feelings of being in end times got me thinking, though: maybe students didn’t need to write the academic essay, at least not always, or not all students. The pandemic, the great accelerator of workplace trends, sparked these thoughts, but, truth be told, with all the epitaphs being written for the death of the English major in recent years, this wasn’t the first time I thought about experimenting with what we write and how we read.

The other source of inspiration for the spring 2022 seminar, which I optimistically titled “Reading Jane Austen for Fun,” was a nexus of arguments advanced by the critic Rita Felski in successive books published across a little more than a decade: Uses of Literature (2008), The Limits of Critique (2015), and Hooked: Art and Attachment (2020). Felski’s unofficial trilogy explores academic literary criticism’s tendency to disregard and disparage people’s everyday uses of literature. Questioning academics’ reliance on “suspicious reading”—a phrase Felski uses in The Limits of Critique to describe interpretative methods whose roots are in twentieth-century Marxist and psychoanalytic thought—the critic demands that we reckon with modes of literary engagement that scholars are too apt to regard as naïve or escapist. Aesthetic encounters, including book clubs and beach reads and all the mundane ways people enjoy literature, have become sidelined, Felski argues, in methods that prioritize the historical and ideological work that texts perform. What’s at stake in taking more seriously people’s passionate if sometimes prosaic encounters with literature? For Felski, literature’s survival as a vital area of humanistic concern depends upon it.2

Sitting in my office, in the fall of 2021, I wasn’t hoping to solve the existential disciplinary crisis by prepping a new Austen seminar. But reading Felski’s disciplinary polemics made me think a lot about Austen’s readers and fans, who, more than most, relish the kinds of literary experience to which Felski urges academics to pay more attention. These experiences include becoming so absorbed in a novel that you momentarily forget your troubles; emerging from your reading more sanguine or clear-eyed; empathizing with another character and finding solace in the perceived commonality of human experience; recognizing aspects of yourself in fictional characters; being reassured or discomfited by that recognition; becoming attached to texts and attached to other readers who share those attachments by, for example, connecting with other readers and fans online, participating in hashtags, and joining JASNA; bringing fictional worlds to life through collective efforts like Bloomsday, the Regency Ball at JASNA’s Annual General Meeting, afternoon tea at the Dickens Universe, cosplay at Comic-Con; being used to characters walking around in your head wherever you go; breathing new life into them through the writing of fanfictions or the making of memes; using literature to scrutinize and define your values, priorities, and tastes; getting your best jokes from books; bonding with others who share your dislike of a text that seemingly everyone else loves; reflecting on how much of who you are derives from the books, movies, and TV shows you’ve loved. Felski’s aim is to foster modes of interpretation more attuned to how people use texts. My own classroom goal was, in some ways, more fundamental: I wanted to increase usage. Naturally, I turned to Austen.

At least as far back as 1973, the year Lionel Trilling offered an Austen seminar at Columbia that was so popular that Trilling had students interview for roster spots, it has been a common story in academia that students clamor for Austen.3 My hope was not simply to capture this demand but also to capitalize on it. Perhaps the stories about students clamoring for Austen are the kinds of stories that people tell each other to reassure themselves that the world is the way they hope it to be. In any case, my Austen seminar filled quickly, maxing out at eighteen, an auspicious sign because I wanted my class to serve as a laboratory for understanding and stoking literary attachments. I speak of attachments to books, characters, and built worlds, but also to people. Janeites, “the first fandom subculture,” trailblazed literary sociability, as cultural critic Virginia Heffernan writes in an essay laying out the case for why Austen fans constitute “the avant-garde of digital culture.”4 With Janeite sociability in mind, we would study Austen as well as Austen cultures, from the mass cultural reception of Austen to the most devoted circles of Austen fandom, from TikTok to JASNA. We’d also cultivate those cultures by producing creative and critical work for Austen fans as well as our own imagined audiences. My hunch, or hope, was that engaging Austen’s fiction like fans would enable students to acquire the fanatical reading habits and literacies for which fans are known.5 That only one of the eighteen students began the semester a self-avowed Janeite was beside the point, but also the whole point. By mimicking a kind of devotion that academic inquiry typically eschews, perhaps my students would discover and experience for themselves the meaning of what Felski calls attachment: “how people connect to art and how art connects them to other things” (Hooked viii).

JASNA networking and the origins of a conference

Jason:

The point was to learn from Janeites. Before the start of the spring semester, I spoke with a few JASNA Regional Coordinators whom I knew through my own participation in JASNA. Susie Wampler of the Southwest Region let me know that my students would be welcome at any of the Zoom events sponsored by the Los Angeles-based community of Janeites, a huge group that routinely draws marquee authors and scholars. When I told Susie that my students would be able to write and create in the genre and media of their choice, she suggested that I speak to Lynda Hall, a JASNA member and professor at Chapman University, who had recently led innovative Austen seminars and written about the experiences in Persuasions and Texas Studies in Language and Literature. Lynda was generous with her time, and I felt inspired and emboldened by her accounts of flipping the classroom, embracing pop cultural iterations of Austen, and giving students the freedom to create their own Austen-inspired cultural artefacts.6 My next conversation, with Carolyn Brown, the Regional Coordinator of JASNA Mississippi, led to a collaboration.

Carolyn:

After the spring of 2020 I retired from full-time teaching from St. Andrew’s, but my “Timeless Jane Austen” class continued to be offered as an English option in the school’s virtual curriculum. In fall 2021, I knew that in the spring I would be teaching the class to an exceptional group of seniors who could handle college-level work. As I was thinking about my future class that October, I received an email from Jason, saying:

I’m teaching a class in the UM Honors College called “Reading Jane Austen for Fun,” and the idea for the class is twofold: 1) to merge three worlds: the worlds of academia, pop culture, and fan culture and 2) to generate original Austen-related content for the wider world, whether on social media, YouTube, the web, or even a regional JASNA event on Zoom or in person.

His timing could not have been more perfect! Regular brainstorming sessions over Zoom commenced, and what came out of those conversations was the idea of a one-day conference to be held at the University of Mississippi. Some of our curriculum overlapped: we both were reading Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion, but he was also covering Emma, and I was including the Shields biography. He would give his students full rein in the planning and organization of the day-long conference, and my students would get the experience of presenting to a wider and more knowledgeable audience.

Jason:

I liked Carolyn’s idea of organizing a conference because it seemed like a natural extension of my course’s organizing philosophy: to have students engage in more authentic forms of intellectual labor, what educators call “authentic assessment.”7 The thinking behind authentic assessment is that the most valuable learning experiences are ones that more closely simulate real-world conditions, for example, by managing diverse tasks in project-oriented work or by addressing an audience beyond the teacher.8 The research on authentic assessment often focuses on STEM and vocational educational settings in which there are obvious continuities between coursework and post-academic experiences.9 For those students whose plan is to pursue graduate study in English, or to become English professors, the most authentic assignment imaginable is the seminar paper. But what about students in general education literature classes, or those taking an English elective for fun, or, for that matter, English majors with plans to go to law or medical school? Like any English professor worth their salt, I am an ardent proponent of the value of the seminar paper, of the transferability of the analytical, rhetorical, and research skills that such an assignment requires. (I’m also happy to tout its unique joys, satisfactions, and epiphanies quirky and earth-shattering.) And, yet, for my money, the versions of authentic assessment that seem best poised to make English studies more interesting to more people are those that give students the option to design their own assignments: i.e., to do what selling-the-humanities rhetoric routinely promises, to connect to a wide variety of creative, intellectual, disciplinary, and professional pursuits.10 Of the eighteen students in my 300-level seminar “Reading Jane Austen for Fun,” four were English majors, with others majoring in Secondary Education, Biology, Chemistry, Biochemistry, Psychology, Urban Planning, International Studies, Journalism, and Integrated Marketing. Three of the students were pre-med, and one was working towards a career in broadcast journalism.

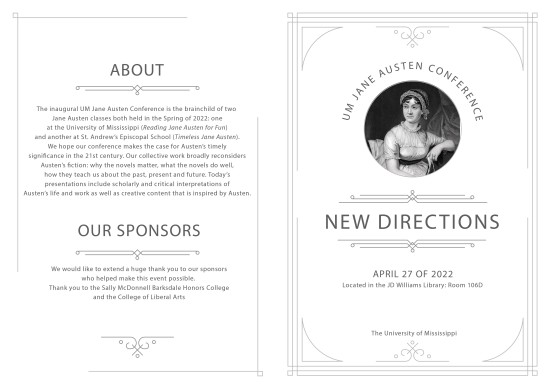

Using a model of authentic assessment empowered this group to pursue projects that aligned with their professional goals and personal interests. For each novel we studied—Pride and Prejudice, Emma, and Persuasion—each student designed what we called a “novel project,” whose punning name conveyed the assignment’s main directive: to create something or do something new, inspired by that novel, for an actual audience (see Image 1). Several students in the class chose to do collaborative novel projects, and at scheduled dates during the semester everyone worked in teams of three to deliver oral presentations on a piece of Austen criticism. This coursework—requiring autonomy, teamwork, and project management—served as scaffolding for the complex work of organizing a conference.11 Because the novel projects were entirely conceptualized and executed by the students, moreover, each project had its own raison d’être, justified by a perceived need as well as an imagined audience. The work mattered to students, and they were fired up to share it.

Image 1: Detail from the Novel Projects Assignment Sheet.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Image 2

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Carolyn:

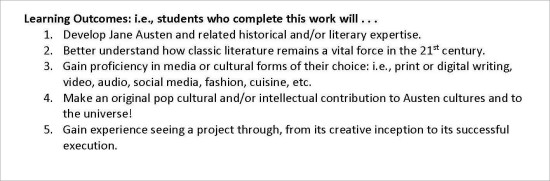

Even though I talked to my students about our collaboration and the April trip to Oxford on a regular basis as soon as my class began in January, what finally made it real for them was receiving the “Call for Papers” from Jason (See Image 2). Now they had a deadline and were directly communicating with a college professor. They also had an important decision to make: what assignment would they submit? Many had already completed projects that would work well for the conference theme (“New Directions”), but they also might want to do something new. The excitement in my class was palpable; I had individual meetings with my students as they fine-tuned their proposals. Jason’s students were then given the difficult task of organizing the variety of projects into coherent sessions.

Our students’ novel projects

Jason:

The range of projects produced during the semester was remarkable. Morgan Whited, a pre-med student, researched Regency-era healthcare after raising questions during class about the Pride and Prejudice scene in which characters debate whether to call a city physician or a country apothecary for bedridden Jane Bennet. Whited’s multi-modal project included a conventional research paper, a BuzzFeed quiz, as well as a Regency-era vade mecum, made with publishing software, called “The Physic Pocket Companion.” Another pre-med student, Josie Long, collaborated with psychology major Alex Bush to produce a YouTube series, “A Hunger for Literature,” in each episode of which the two foodie bibliophiles recreate and discuss the history of a culinary dish that appears in a different Austen novel. While the food is cooking, they discuss the text in a segment titled “Simmering Thoughts.” Discovering that she’s not a fan of white soup, Long quips on camera, “it tastes better than it smells.”

Several short films were produced over the course of the semester. Inspired by Heidi S. Bond’s viral law review essay “Pride and Predators,” Marika Hall and Reese Anderson teamed up to write and direct a retelling of Pride and Prejudice, focusing on a serial rapist named Wickham. Olivia Maurer, a student of public policy and urban design, created a French-New-Wave-style film focusing on an afternoon in the life of a perambulating college student during the Covid lockdown. Hoping to enjoy the kind of freedom Keira Knightley’s Elizabeth Bennet finds walking across an English heath, Maurer’s quixotic heroine discovers a pedestrian-unfriendly, strip-mall-lined terrain, where she runs into catcalls and reckless drivers. Hall, Anderson, and Mauer joined forces on their next film, a takeoff on The Bachelorette, in which Emma Woodhouse holds all the cards and chooses her man. Journalism student Catherine Jeffers used Adobe InDesign to create the imaginary front pages of the imaginary newspapers The Pemberley Post and The Highbury Herald, including relationship advice columns from Elizabeth Bennet and Emma Woodhouse.

While some students worked in the same medium all semester or focused their efforts on developing serial content (e.g., on YouTube or Instagram), others used the freedom the course allowed to explore a variety of projects. Azurrea Curry, an education student, began the semester by designing a Pride and Prejudice game for middle-school students but pivoted in her next project to a multi-platform fashion vlog, including an Emma-Chamberlain-style thrifting video diary, following Curry and friends’ search for clothing inspired by Austen’s Emma. The project included TikToks showcasing different characters’ styles as well as imaginary Pinterest boards created by those characters. For her final novel project, Curry teamed up with Whited (the author of “The Physic Pocket Companion”) to create a classroom poster featuring silhouettes of Austen characters, arranged according to kinship relations and social networks, conveying information about the characters’ dispositions and occupations.

Image 3: Detail from Novel Project Success Rubric.

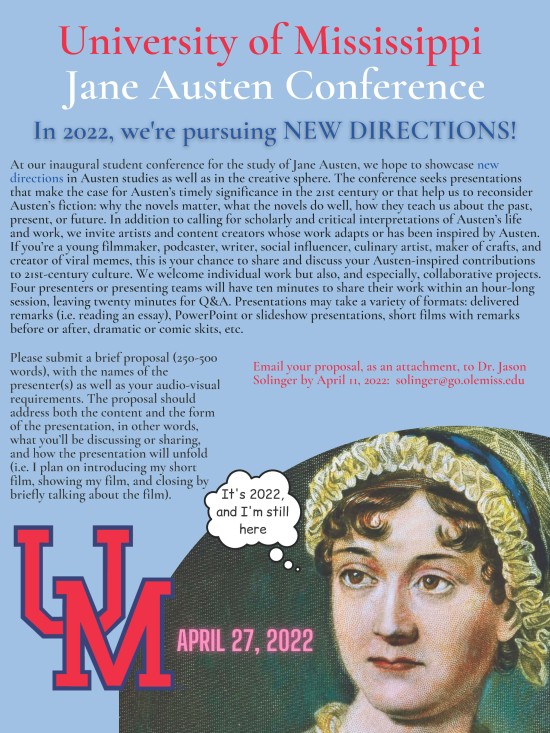

Such projects may have been designed for educators, students, and Janeites, but more importantly each involved meta-reflection through which the students had to think seriously about what they were doing and why. Students were required to submit a written self-assessment with each project, describing how their work satisfied the grading rubric’s four evaluation criteria: i.e., Austen bonafides; intervention or vision; success in chosen media; and consideration of audience (see Image 3). Some projects were obviously conceptualized for Jane Austen superfans, but even these—owing to the students’ careful consideration of audience, media, and aims—were so clearly and coherently designed that they touched a broader audience of cultural consumers, including bibliophiles, social media users, tv addicts, the meme-obsessed, and the Austen-curious. A case in point is Emily Suh’s podcast episode, “Enemies to Lovers: Pride and Prejudice,” conceived as one installment of an ongoing series titled “Two Women and Fictional Men,” featuring Emily and a co-host (the “two women” in the title) discussing heroes in romantic fiction and films, focusing on a different text in each installment. Suh never intended to produce more than one episode. By conceptualizing the podcast as part of a series for a particular audience, with its own literacy and set of interests, however, she achieved a confidence of address too often lacking in academic papers.

A similar confidence—a mastery of tone and vocabulary as well as a command of structure—characterized much of the work produced that semester, from winking Buzzfeed quizzes to lifestyle magazine pieces such as Kappy Eastman’s parody of a Southern Living feature offering readers a glimpse of Mr. Collins’s well-appointed cottage. Working in media of their choice, students were well positioned to demonstrate and develop their literary expertise, as became evident both in their self-reflections and in the projects themselves. AG Robinson, for example, created her “Pride and Proposals” Instagram account, with accompanying TikToks, imagining how Austen’s characters would represent themselves as well as the salad days of their courtships and married lives. A twofer, the project simultaneously analyzed Austen’s characters and twenty-first-century (social-media) conduct. Over the course of the semester, I often had to ask students to expound upon their project proposals, in some cases because my GenX self hadn’t yet encountered or fully processed the pop cultural materials with which they were working. What’s a Book Tok? What do you mean by video essay? a mood board? a character’s enneagram? These conversations were generative, offering additional opportunities for students to clarify their visions or comprehend, with an anthropological eye, the culture or cultural artefacts they thought they knew well.

Carolyn:

Jason’s “Call for Papers” (CFP) invited both scholarly and critical interpretations of Austen’s life and work as well as an opportunity for “artists and content creators” to send projects whose work adapts or has been inspired by Austen. He added: “If you’re a young filmmaker, podcaster, writer, social influencer, culinary artist, maker of crafts, and creator of viral memes, this is your chance to share and discuss your Austen-inspired contributions to 21st-century culture.”12 Since my students had already been operating in those various roles over the course of the semester, they had work prepared to share. Their task now was to make their projects conference-ready and to be able to explain the genesis of their ideas to and answer questions from a knowledgeable audience other than myself and their peers.

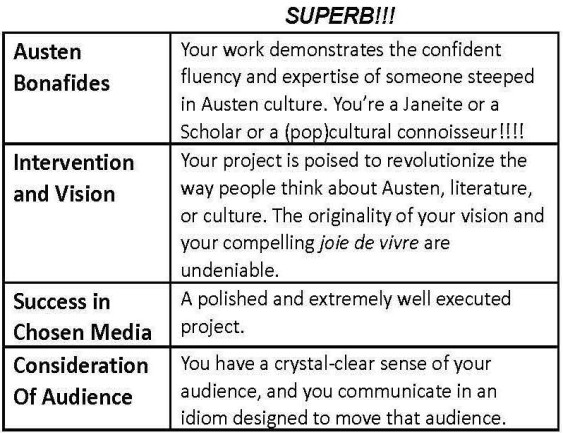

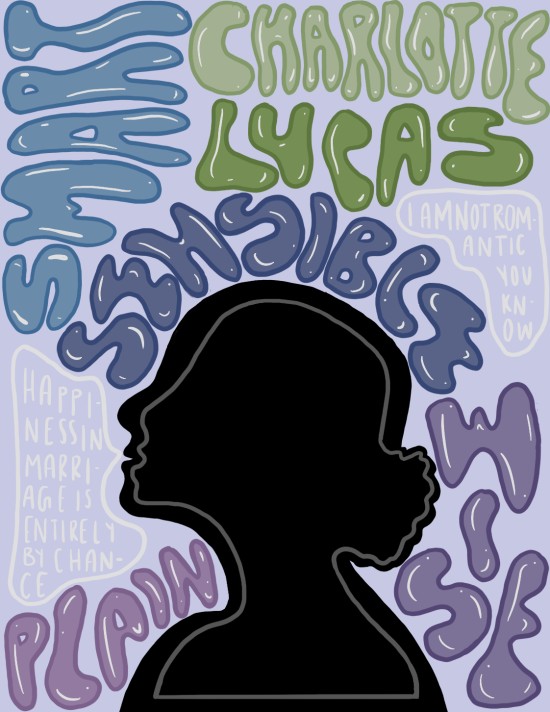

Pride and Prejudice was clearly a popular choice among students. Several students gravitated towards character-centered social-media fanfictions. In my class, for instance, one student created a blog entitled “Mrs. Gardiner’s Guide to Mothering” that dispensed thoughtful motherly advice taken directly from the novel. Posts, including “How to Help Your Daughter Avoid Wicked Men,” were written as epistles (“Dear Readers”) in Mrs. Gardiner’s voice and illustrated with appropriate Regency-era illustrations. In one entry, “Parenting a Flirty Daughter,” Mrs. Gardiner uses Lydia as an example: “My niece, Lydia, was such a great flirt that she caused great trouble for her family, especially her sisters. Luckily the issue was resolved. I talked with her in a serious manner about the wickedness of her actions, but she would not listen. I did my best in parenting her, but sometimes you cannot force them to understand the consequences of their actions.” Her answer? Better parenting (although Mrs. Bennet is not mentioned explicitly): “To avoid having an overtly flirty daughter, you need to have them grow up civilly. Demonstrating desired good behavior can help you raise a sensible daughter.” Another submission that required a close analytical reading of the novel was “Jane Bennet, Unmasked (a Monologue),” a video that exposes Jane to the world by displaying her two sides: the Jane who hides her feelings all too well (and to her detriment) and the Jane who screams her true feelings for Mr. Bingley into a pillow or at a mirror. This student brought Jane to life in a video monologue that illustrates the painful agony of what Charlotte warns Elizabeth about the morning after the ball: “‘it is sometimes a disadvantage to be so very guarded. If a woman conceals her affection with the same skill from the object of it, she may lose the opportunity of fixing him’” (23–24). This visual depiction of Jane’s character shows how she suffers in silence. Another clever, artistic Austen-inspired art project depicted a silhouette of Charlotte Lucas in a colorful Warhol-like poster using the graphics editor app Procreate, with Charlotte surrounded by the words that define her best and are consistently used to describe her (see Image 4). Other projects included “mr.collins_the greatest,” an Instagram account featuring posts by the clergyman as he searched for a wife and shared his (not so) Christian wisdom; “Keeping up with Caroline Bingley,” a hilariously funny video that renders Caroline as a contemporary Kim Kardashian; and modern-day text exchanges between Mrs. Bennet and her daughters, full of gossip as well as matrimonial encouragement and advice.

Image 4: Silhouette of Charlotte Lucas by Jasmine Bennett. Bennett created this work using Procreate, a digital illustration app.

When they presented their projects alongside Jason’s students on conference day, it was one of my proudest moments of teaching in my 30+ year career. Their work was imaginative and original, and they presented to their college counterparts with confidence and poise. I came to the same conclusion as Lynda Hall, who remarked after teaching a similar class and publishing her findings in Persuasions On-Line: “I was astounded at the quality and creativity of the work, and I was also reassured that the students were learning as much if not more from these projects as they would have from a traditional research-based term paper.”

Coda/continuation

Jason:

It’s funny how some of your favorite moments of teaching are surprises. Early in the semester, I offered my students a choice: take a final exam or organize a conference. Some of you reading this are probably thinking: “Of course, they chose the conference. Anything to get out of a final exam.” Perhaps, but consider how often we counsel young people to follow their bliss when choosing a career. The conference wasn’t simply more fun than a final exam. It also required a mixture of intellectual, administrative, collaborative, project- and process-oriented labor, in other words, a more diverse set of experiences. It wasn’t just schoolwork that resembled real-life work; by any measure, it was the real thing.

Although I supervised the process and designed the original call for papers, the entire success of the event was in their hands. A program committee vetted and sorted the presentation proposals that Carolyn’s students submitted via email. With their shared Austen literacy, the program committee members shaped the conference, organizing the presentations into coherent panels, coming up with panel titles, and assigning their classmates as panel respondents. In coordination with university staff and administration, a design committee created a conference program and promoted the event on social media (see Images 5 and 6). A hospitality committee secured a conference location, UM swag bags, lunch passes for the visiting high school students, and a special tour of campus. Those who didn’t join committees or serve as respondents presented their work on panels, often in a modified form, again having to closely consider the parameters of the discourse environment: what’s a conference, who’s my audience, how does the work relate to others on the panel, what can I communicate or demonstrate in the time available?

Carolyn:

The conference was a great success. One of my personal goals for it was achieved: to expose high school seniors to college-level discourse and have them present to a wider audience. But more than that, I found my students completely engaged with Austen’s novels in exciting and transformative ways. Just as I followed my passion in creating the class, they followed their passions, designing projects that connected with them personally while using twenty-first-century technology. The title of my class, “Timeless Jane Austen,” resonates more deeply for me now, seeing my students creating contemporary projects inspired by classic literature. One of my students agreed: “What I took away from the conference was how pervasive Jane Austen is. At the end of the day, no matter what we do, we can’t escape her. Over two hundred years later, we’re still talking about her writing” (Eastman).

Jason:

The conference was a success for the same reasons our semesters were successful. Our students consistently reflected on what they were doing, why they were doing it, and whom they were addressing. Authentic assessment may require rethinking conventional class design, but it is easy to implement when it is student-centered and starts with asking students what they want to do. This doesn’t mean eschewing disciplinary knowledge or discipline-specific modes of communication. In fact, working within the discipline or subdiscipline—in our case, Austen studies—enabled students to cultivate a lingua franca that allowed them to learn from and work with each other while pursuing diverse interests. I mention “Austen studies,” but as I indicated earlier in this reflection, ours was also a foray into Austen fandom. The class was student-centered but also pleasure-centered to the extent that students were encouraged both to have fun and, since fun is contagious, to spread joy. A former version of myself would have found the last sentence too cringeworthy to mull, let alone write. Isn’t it obvious, however, that what makes people invested in the literary arts is the enjoyment they find in them? (Or some version of enjoyment, if not pleasure, solace, escape, self-care, self-affirmation, and even selfish self-regard?) Our students certainly had fun with Austen’s fiction, but the lion’s share of that fun derived from the conversation, laughter, and ironic and knowing sociable exchanges that characterize fan communities and generate creative output. The momentum we built over the course of the semester may have culminated in the conference, but it did not end there. Kappy Eastman wrote a news story about the conference, which was picked up by the College of Liberal Arts and published on the university’s webpage. Marika Hall entered a submission in JASNA–SW’s Young Filmmakers Contest; her Wes-Anderson-style cinematic retelling of Persuasion took third prize and is available on YouTube. Emily Suh began working on her senior thesis, focusing on feminist appropriations of Austen. And for a long time, students kept exchanging Austen memes and literary cheer on the class’s GroupMe, which still exists.

NOTES

1In Jane Austen: A Life, Carol Shields writes, “Pride and Prejudice can be seen as a palimpsest, with Jane Austen’s real life engraved roughly, enigmatically, beneath its surface.” I believe Persuasion can be read similarly, which makes these two novels interesting to read and compare once students have a basic knowledge of Austen’s life. For further discussion of this idea, see Shields (69–70).

2In The Limits of Critique, Felski argues that “questioning critique is not a shrug of defeat or a hapless capitulation to conservative forces. Rather, it is motivated by a desire to articulate a positive vision for humanistic thought in the face of growing skepticism about its value. Such a vision is sorely needed if we are to make a more compelling case for why the arts and humanities are needed” (186).

3For Trilling’s account of interviewing students for his Austen seminar, see the last essay he wrote, “Why We Read Jane Austen.” For a more recent account of the popular Austen seminar, see Patricia A. Matthew’s essay, “On Teaching, but Not Loving, Jane Austen.”

4See Heffernan’s Substack article, “Jane Austen Fans Are the Avant-Garde of Digital Culture” as well as David Barnett’s “OMG! It’s Jane Austen . . . the TikTok Generation Embraces New Heroine.”

5The French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser, channeling Pascal, says of church attendees: “Kneel down, move your lips in prayer, and you will believe” (114). I wasn’t hoping, along these lines, to recruit students into what insiders and outsiders cheekily describe as the cult of the Janeites. I was hoping to expand our ways of using fiction by adopting the projects and approaches pioneered by Austen’s fans. These include parody, pastiche, meme-work, cosplay, and community building.

6See Hall’s essays in Persuasions On-Line and Texas Studies in Literature and Language.

7See Ashford-Rowe et al; Jessop and Maleckar; Wakefield et al; Colthorpe et al.

9In “I’m What’s Wrong with the Humanities,” Ross Douthat describes the internet-age humanities crisis as a futile “quest . . . to sustain relevance and connection—to politics, to professional life, to whatever trends appear at the cutting edge of fashion, to the idea of progress.” Although I agree with Douthat’s sense that the humanities are often marketed in such terms, I don’t agree with his assessment that the “quest can end only in self-destruction when the thing to which you’re trying so desperately to bind yourself (the culture and spirit of the smartphone-era internet, especially) is actually devouring all the habits of mind that are required for your own discipline’s survival.” Douthat concludes emphatically: “You simply cannot sustain a serious humanism as an integral part of a digitalized culture.” The experiences we relay in this article suggest otherwise.

10If I sound cynical about “selling the humanities,” I’m more on board the selling-the-humanities train than Stanley Fish, whose 2018 Chronicle of Higher Education article “Stop Trying to Sell the Humanities” argues that all attempts at selling the humanities are self-defeating. “The justification of the humanities is not only an impossible task but an unworthy one, because to engage in it is to acknowledge, if only implicitly, that the humanities cannot stand on their own and do not on their own have an independent value.” I’m less concerned about the question of the independent value of the humanities than I am with questions about how to get students excited to read, think about, and use literature. The humanities might not need to be independently justified anyway; see Nicole LaPorte’s “Da Vinci Was a Double Major.”

11For a capsule history and interrogation of the metaphor of scaffolding in educational theory, see Boblett.

12I think using this language rather than “students” is liberating and suggests practical, real-world applications—rather than simply completing an assignment for a class.