It is perhaps not surprising that Pride and Prejudice, arguably Austen’s most famous and influential novel, has such a strong presence in her final home. Nearly ten percent of the books and artefacts held at Jane Austen’s House in Chawton are either directly or indirectly connected to the writing, publication, and ongoing legacy of the novel. Fascinatingly, many of these objects have lives and biographies of their own, which in turn deserve further research and dissemination. Indeed, so rich is the collection that there remain multiple avenues of investigation and many stories left to discover. This paper will explore the presence of Pride and Prejudice at Jane Austen’s House though three distinct areas: the printed text; the lived experience of Austen and those who called it home; and the author’s voice, as heard through her letters. We will look at physical objects, the interiors and decorative choices made at the house, and will look back into the past to discover new potential influences on the shaping of the novel.

From the very start of its life as a museum, the house would be a site of storytelling and interpretation, as over nearly eight decades, first T. Edward Carpenter, then the Jane Austen Memorial Trust, and now the team of staff and trustees that care for the house today gathered and assembled the objects that would tell the story of Austen’s writing as well as communicating her life at the house. Books, furniture, paintings, and artefacts have been generously donated, purchased at auction, or bequeathed to build what is today one of the most significant collections of Austen-related material anywhere in the world.1 This significance is double layered—not only are the objects that make up the collection of exceptional quality (as we shall see), they have an added layer of emotional impact: in a sense, all these objects (whether a precious holograph letter, first written by Austen herself in the house, or a late twentieth-century piece of fan art) are coming home, back to the house that nurtured and supported the creation of these extraordinary works of literature.

![]()

Pride and Prejudice was the second novel Austen had published while living in this house. It was begun, like Sense and Sensibility, many years earlier, during the Steventon years; after the move to Chawton, Austen returned to the manuscript, “lopt and cropt” and revised it into the novel that we know and love today. It followed Sense and Sensibility into print in January 1813.

And it is in 1813 we start, as we begin our exploration of Pride and Prejudice at Jane Austen’s House, not just behind the scenes, but behind locked doors, as we enter the Collections Store. This treasure trove (which is always accessible to researchers by appointment) holds artefacts ranging from first editions to family diaries to silhouettes to exquisitely worked lace. It is the bookshelves that catch the breath in this special room. Here Martha Lloyd’s Household Book rubs shoulders with Austen’s copy of Elegant Extracts and Excursions from Bath, while both are surrounded by nearly two centuries of first editions. The questing hand of the bibliophile can pass over garish 1970s paperbacks and head back in time, moving from the first Penguins to Chapman’s editions, then back again to the pastel-prettiness of Charles Brock and the fin-de-siècle glamour of the Peacock edition. The hand moves again, slowing as it reaches the 1833 American first editions, before finally halting on the bottom shelf, where the magnificent collection of first first editions resides, each in its own beautifully made bespoke box.

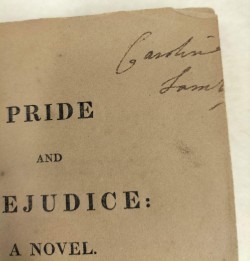

There are four first editions of Pride and Prejudice in the collection at Jane Austen’s House, and all but one has its own story to tell. I strongly suspect that the fourth copy, the silent edition, does have its own secrets to tell us, but it requires further research to help it find its voice. The other three copies are the Godmersham edition, the Caroline Lamb edition, and the Thomas Meautys edition.

The Godmersham edition was one of Austen’s own author’s copies, in her own words—one of “the two Sets which I was least eager for the disposal of” (29 January 1813). It was sent directly from the publisher to her brother Edward Austen (later Knight) in Kent and was later passed down to his daughter Marianne Knight. Much later it and the rest of the Godmersham set were purchased by Charles Beecher Hogan, who bequeathed them to the museum.

The Lamb and Meautys editions share very similar bindings, with Italian marbled-paper boards and sheep-leather bindings. They also show similar patterns of wear on the front and back covers. This wear pattern comes from being held and read: the books are worn exactly where your hands would sit as you hold the book open to read it. The Meautys edition has been read and handled rather more than the Lamb edition. The spines are also different. The Lamb is less ornate and has no author’s name. The Meautys is considerably shinier, and the person who commissioned the binding knew the author’s name, if not quite how to spell it, as we can see from the “Austin” on the spine. The similarities do open the possibility that this rebinding work may have been carried out by the same bookbinder, but more research is needed into this question.

Neither of these texts—in fact, none of these first editions—is in the original state in which it would have been sent out from the publisher or purchased from booksellers in 1813. Instead, these books would have been almost paperbacks, contained within blue “publisher’s boards” with a simple paper label with the title and price of each volume attached to the spine. The pages would have been uncut.

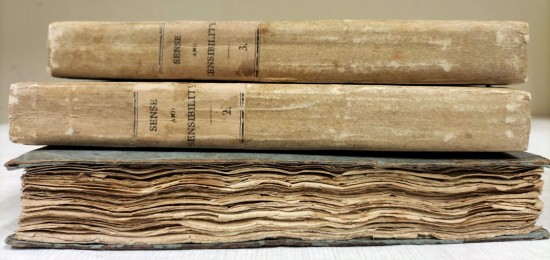

Austen novels in their original boards are very rare, and we don’t own a copy of Pride and Prejudice in its publisher’s boards, but we do own Sense and Sensibility, Emma, and Persuasion/Northanger Abbey. The photograph below shows two first editions of Sense and Sensibility, which like Pride and Prejudice was also published by Thomas Egerton, with the publisher’s boards copy next to a bound edition. You can see the difference in size, and the rough edges of the pages in the original edition. After purchase, and probably after their first reading, owners would have their copies rebound in leather to match their own libraries, or the current fashion. Only a small handful of books didn’t have this treatment, and we are lucky to have such a good collection of the unbound works at Jane Austen’s House.

|

|

| Two first editions of Sense and Sensibility, in publishers’ boards (left and below) and bound. © Jane Austen’s House. |

Comparing the bindings of these three books is fascinating. The binding of the Godmersham editions is very tight, and it is difficult to open the books fully, without the fear that one will crack the spines—something that as a reader one might not care about but as careful custodians of precious items, we are very keen not to do at Jane Austen’s House. The tightness of the binding opens up discussions about the purpose of these books. The Godsmersham editions became “museum pieces” not long after Charles Beecher Hogan had them rebound, and today they, and indeed all these books, which started their lives as tactile objects, as physical tools to communicate the metaphysical, have become things not to be touched, to be handled with great care, still things. At the same time, the story they hold has remained a living, evolving thing with a rich tangible and intangible history of its own, way beyond the confines of the printed word.

Caroline Lamb is most famous today for her rather disastrous affair with Lord Byron, which erupted and burnt out over six months in 1812, during which period she described him, or perhaps defined him, as “mad, bad and dangerous to know.” Her relationship with Byron is central to understanding her life and her legacy, but we can do better than to define a woman solely by the men in her life. She was a clever, complex woman, who rather fascinatingly was educated at the successor of Austen’s own Reading Abbey School, which by then was operating in Hans Place—where later Austen would stay with her brother Henry while overseeing the publication of her novels. Mary Russell Mitford was also a pupil there. Like Austen, Lamb was highly educated, multilingual, enjoyed music and the theatre, and had a biting gift for satire and mimicry. In 1816 she published Glenarvon, a gothic novel that included not just portraits of herself and Byron but also scathing, and barely concealed, caricatures of prominent society members. This, and her ongoing, very public obsession with Byron, resulted in not just the breakdown of her marriage, but also her virtual expulsion from the world of “polite society.” Her last years, dogged with mental and physical ill health, were spent at Brocket Hall, a considerable estate in Hertfordshire, which is just a few miles from the village in which I grew up. (Brocket Hall, with its grand avenues and its lake, will always be Pemberley for me.)

Caroline Lamb's copy of Pride and Prejudice. © Jane Austen’s House.

It is very tempting to imagine that the patterns of wear on this edition were made by Caroline herself, as like so many of us she turned again and again to the novel, as she needed comfort and escape—but she probably didn’t know this book in this binding. When the book was rebound, her signature was partially cut away. This suggests that she might have read it in its original boards: it was fairly common practice to cut down worn page edges when rebinding. Luckily, more than enough of her signature has survived for us to know who the original owner was.

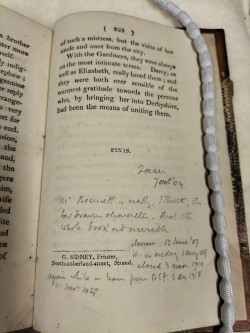

Tinged with celebrity (and indeed notoriety) though the Lamb and Godmersham editions are, it is the Meautys edition that is my favorite (and I am aware what a privilege it is to have a favorite first edition of Pride and Prejudice!). It is the copy that is the most worn, that most has the marks of hands holding it, that has been read, and reread. It is also the volume that tells us the most about the person who did all this reading. The reader was careful, methodical, and deeply engaged with the text. There are pencil annotations at the back of every volume, which show a reader who wants to make sure that he or she is entirely a part of the text and completely understands it. I have called it the Meautys edition because of the Thomas Meautys bookplate inside the front cover, but I am still endeavoring to discover exactly who its most avid reader was.

Pencil annotations volume 3 of the Meautys Pride and Prejudice.

© Jane Austen’s House.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

At the back of the first volume is a list of the “Bennett” sisters, as well as notes of other key characters in the plot, including the Bingleys and the Lucases. By the second volume, the notes have expanded to include what is effectively Mrs. Bennet’s family tree, and the ages of her five daughters. It is the final volume that contains the most notes and is the most interesting. Here we find the inner thoughts of the reader, who has written: “Mr Bennett, is really, I think the best drawn character, and the whole book admirable.” There is also a record of all the times that this reader read and finished the book: October 7, 1904, then again on June 12, 1907, and again on August 1, 1909. This reader read it aloud on March 3, 1910. Most poignantly, “again whilst on leave from the B E F. 5 May 1918.” The BEF was the British Expeditionary Force, which means that the reader was male (as we could have possibly suspected from the affinity with Mr. Bennet), and that he was in active service at the front in the First World War. For this reader, as for so many others across the decades, but particularly in times of conflict, Pride and Prejudice represented an escape, as well as a vision of an idealized England.

This reader returned home to read his copy, but there were copies of Pride and Prejudice even at the front. The novel was included in a list of books put together by the Oxford tutor H. F. Brett-Smith specifically for severely shell-shocked soldiers (Sutherland 53). Here is Austen, acknowledged as being key to improving what we would now call mental health. Many copies of the novel were sent out to hospitals both at home and on the front line, and they were read and absorbed and do seem to have provided the comfort that Brett-Smith hoped. Rich as our collections are, we are missing one of these precious, incredibly rare Forces Editions, and we would love to add one to the collection.

![]()

The collection at Jane Austen’s House is rich in physical objects, but in many ways it is the house itself that is the most precious artefact of all. The building sheltered and offered refuge to a small, all-female household, who worked together to enable the creation of some of the most innovative and most inspirational works of literature ever created. Our books, jewelry, and textiles are the personal relics of our own secular saint—things that were once in use, items that were produced to be handled or worn or washed. Now they are precious things, imbued with meaning and value beyond anything that could have possibly been imagined at their creation. The objects live behind glass, or behind locked doors—they are in a form of stasis, of suspended animation, as they live on in a strange half-life.

The house, by contrast, is fully alive. It is an old, old place, and predating, as it does, the Austen household by some 300 years, it has had a life both before and after Jane Austen. Like all old houses, it breathes and moves with the seasons; as the light changes, so does its mood. I have watched sunlight dance across the drawing-room floor and heard winter storms turn the chimneys into roaring, howling musical instruments. But I can’t experience the house quite as Austen would have done. I cannot know the two-tiered existence of a genteel home in which the cook and the housemaids are hard at work in the kitchens and scullery while the “family” sews, or plays the piano, or . . . writes. But despite the changes in the use of the house and in our ways of life, it still has a huge deal to tell us about Pride and Prejudice and Austen’s lived experience.

Not all the links to Pride and Prejudice are in plain sight; they don’t appear in the display cases, on the walls of family rooms, or even on the shelves of the Collections Store. Hidden in the bakehouse is a remarkable piece of graffiti that potentially opens a new window onto our understanding of the composition of the novel and, indeed, of Austen’s interactions with both historic and contemporary folklore. The bakehouse is part of a run of single-story buildings that make up the other two sides of the courtyard that sits behind the main house. Comprised of cellars, storerooms, stables, and the bakehouse itself, this part of the site has always played a vital role in supporting the running of the house (and for many centuries the household), and remains its operational heart, despite the many changes in lifestyle and technology over the centuries since it was first built.

The bakehouse is a relatively small room that contains a brick-built bread oven, which would have been used by the less fortunate of Chawton as well as by the household, and a heated washtub, known as a “copper,” which allowed for the heating of large quantities of water for both washing and brewing. The well is situated conveniently just outside its front door. There is also a cellar underneath this part of the building. It is the door to the cellar that is particularly fascinating and hides the secret that we are looking for. On the back of the door is carved a perfect “daisy wheel,” six interlocking petals within a circle, which was made with a pair of compasses or, possibly, sheep-shearing tools (Gaskill 135). It isn’t particularly deep, but it cuts across the panels that make up the door and through the remaining layers of whitewash. It is an apotropaic or protective mark, more commonly known as a “witches’ mark.” While their exact purpose and semiosis is unclear, witches’ marks seem to be intended to give protection for people, livestock, and produce (Gaskill 135). The daisy wheel or hexafoil mark is one of many found carved into openings—fireplaces, windows, and doorways—across the U.K. (“What Are Witches’ Marks?”). A survey carried out by Historic England in 2018 found that of all the variants of markings that have been made into the structures of buildings, this mark is the most common, so common that Nick Molyneaux of Historic England described it as the “classic” mark. It was in use for many hundreds of years across a wide geographic area and seems to have survived many official changes in belief and religious practices.

|

|

| Bakehouse cellar steps with “daisy” or hexafoil mark on door. © Jane Austen’s House. | |

Its presence at Jane Austen’s House is fascinating. It is not surprising that a house of this age has witches’ marks (indeed there are others, albeit more simple scratch marks, carved into the beam above the kitchen fireplace), and it would perhaps be more anomalous if we did not. Instead, the fascination lies, first, in what it can tell us about literacy and the preservation of memory, activity, and belief—in essence, the creation of history. There is very little in the written record relating to witches’ marks, or indeed the wider associated practices of protective magic. This belief system was still in place right up until the twentieth century, and yet there is no true codified record of what the person who made the daisy wheel on the cellar door believed it would achieve, or what motivated them to do it. This belief system, apparently, was largely carried out by people who had no or limited access to literacy and thus no way of handing down their unfiltered thoughts and beliefs to the following generations. These stories, unlike those of Jane Austen, were not fixed to paper and have therefore been lost. It is a poignant fact that a silence looms large over the bakehouse, former scullery, and cellars, where even the names of the vast majority of people who worked have been lost, let alone their thoughts and beliefs, while the words written in the main house, a mere twenty-five feet across the courtyard, have been published and analyzed, dissected and disseminated for over two hundred years.

It is unclear when the witches mark at Jane Austen’s House dates from, and I certainly don’t claim that it was created by either Jane Austen or her family—far from it. It is likely to be at least a century older than the house’s Austen era, and many similar marks date from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries—a period of great unrest and social transformation. A pair of hexafoil marks found at Shakespeare’s Birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon have been placed at the top of a staircase leading to a cellar used to store beer, and they most likely date from the early 1600s, when Shakespeare leased the building to a publican (Molyneux). These marks and the marks at Jane Austen’s House are in a very similar position: a stubby wooden staircase comes up from the cellar floor, and the daisy mark is at about chest height for anyone, or anything, that might want to enter, or come out from the cellar.

This association between brewing (and indeed breadmaking) and protective marking is further reinforced by information to be found in the transcripts of sixteenth-century witch trials, where we do see some indicators of this belief system, both the supposed practices themselves and the actions people took to try and overturn them. Most relevant are the records of the witch hunt that took place in the Essex village of St. Osyth and the surrounding parishes in the spring of 1582, as recorded in a pamphlet entitled A True and Just Recorde. A True and Just Recorde is almost a perversion of an Austen novel, for here too we find “three or four families in a country village,” but what unfolds is not a satire on courtship in polite society but rather a disturbing, true story of families, and women in particular, turning against each other, and even against themselves. It is a story of an extensive witch hunt, played out against a backdrop of poverty, disease, and mistrust, and it reveals a much darker side of rural life, as neighbor informs on neighbor, while accusations of witchcraft—and, strikingly, admissions of witchcraft—multiply.

In Marion Gibson’s excellent book on the St. Osyth witch trials, we see some of this folk belief in practice. We meet the Carter family, who tried to overturn a curse they believed had been placed on their brewing vat. Beer making at the time, and indeed for many centuries, including in Austen’s time, was most often carried out at home. After several hours of boiling water, infusions with hops and flowers, and fermentation, the result should normally be beer or ale, depending on the mixture and the strength. But on this day, the Carters tried twice, but both times the mash failed to produce alcohol. Instead, the mixture stank and had to be “put into the swill tubbe” for the pigs. They attributed this failure to witchcraft, and their remedy to “unwitch” the vat was to call for their son John and tell him “to take his Bowe and arrowe and to shoote to make his shaft or arrowe to stick in the Brewing” vat (Gibson 151). After a couple of attempts, the arrow stuck, and, on a third attempt, they were able to brew proper beer—the curse having been lifted, by the intervention of iron. This use of iron is something we see repeatedly in these “unwitching” practices, closely linked with the act of nailing a horseshoe above the door.

Limited though the evidence is, it suggests that the witches’ mark carved into the door of the bakehouse cellar was placed there to protect both the brewing and breadmaking process and to keep the resulting beer from going sour. The St. Osyth witch trials are a disturbing yet fascinating example of what can happen when women’s culture—that interconnected network of support, gifts, and knowledge, documented so powerfully in Deborah Kaplan’s Jane Austen among Women—goes wrong or when it is disrupted and distorted by the arrival of a powerful male presence. In the case of the St. Osyth witch trials, that male presence was Bryan Darcy, the uncle of the local lord of the manor and a powerful member of the dominant local gentry. He investigated the initial claims of witchcraft, which were bought to the door of the manor house, and over the next six weeks voraciously investigated multiplying accusations and counteraccusations of witchcraft, eventually preparing a case against fifteen people, the majority of whom were women, from several different villages. All were of significantly lower economic status, and the techniques used by Darcy to obtain his information were manipulative and played heavily on these power imbalances.

Among the women accused, questioned, and ultimately executed for witchcraft was an Elizabeth Bennett (whose name was spelt with a double t). She was named as a witch by her neighbor Ursey Kemp, who was the very first woman investigated by Bryan Darcy. Elizabeth held out against Darcy’s questions “as well as she could,” in Gibson’s words, but, after being threatened with burning and hanging by Darcy, did in the end admit to having “a pot or pitcher stool under her stairs in which her spirits [familiars] slept on wool” (Gibson 70–71). One of these familiars was a black dog called Suckin, and in her confession, Elizabeth Bennett told Darcy how this familiar had plagued her neighbors and caused trouble across the village. Once Darcy had compiled his evidence, Elizabeth Bennett was charged with killing William and Joan Byatt by bewitching them. When the time came for the trials, held at the Chelmsford Assizes in May 1582, she chose a different path to many of her co-accused and did not contest the indictment against her. She did not stand trial, and, according to the justice of the time, was sentenced to be hanged for witchcraft (244).

The pamphlet A True and Just Recorde, which featured both Darcy and Elizabeth Bennett’s names so prominently, was published in the autumn of 1582. Perhaps surprisingly given modern preconceptions of the period, it met with considerable criticism. Darcy’s questioning techniques, and indeed his motivation for investigating, were heavily influenced by the French (and therefore Catholic) Jean Bordin. In Elizabeth I’s Protestant England, anything Catholic was automatically viewed with suspicion, and in 1584 The Discoverie of Witchcraft, a vigorous rebuttal of witchcraft trials and accusations, was published by Reginald Scot, a theologian and scholar whose work effectively discredited the very idea of witchcraft and magic (Gibson 234). Reginald Scot was from Kent and spent much of his life living in the village of Brabourne, which is less than eight miles from Godmersham. The Scot family of which he was a member intermarried with the Knatchbulls and the Brydges,2 alongside many of the finest Kent families.

And so it is that we find Jane Austen in Kent in 1796, talking with a Miss Fletcher, the daughter of the last Scot of Scot Hall, and discussing Camilla and all things gothic. Austen wrote to Cassandra in 15–16 September 1796:

Miss Fletcher and I were very thick, but I am the thinnest of the two—She wore her purple Muslin, which is pretty enough, tho’ it does not become her complexion. There are two Traits in her Character which are pleasing; namely she admires Camilla, & drinks no cream in her Tea.

Is it possible that during this conversation with Miss Fletcher, the story of the ancestor who wrote against Bryan Darcy and in support of women like Elizabeth Bennet was mentioned amongst their discussion of contemporary novels? Austen goes on to tell Cassandra that Miss Fletcher is unrepentant over her failure to write to Lucy Lefroy:

Miss Fletcher says in her defence that as every Body whom Lucy knew when she was in Canterbury, has now left it, she has nothing at all to write to her about. By Everybody, I suppose Miss Fletcher means that a new set of Officers have arrived there.

We know from Cassandra Austen that it was at about this time that her sister started work on “First Impressions,” the novel that would become Pride and Prejudice. . These conversations reported by Jane are so redolent of Lydia Bennet and the quartering of the militia at Meryton that it seems to be too much of a coincidence that this conversation was not an influence, however slight, on the characters and plotlines she was creating. Is it therefore also possible that during this visit, or even a previous one, the family story of Darcy and Elizabeth Bennett was discussed, and their names found their way into Austen’s famous novel? It is also worth remembering that our Darcy is also “bewitched” by Elizabeth.

It is difficult to know if Austen would ever have seen this witches’ mark. The all-female household of Chawton Cottage included a cook and housemaids, as well as visiting washerwomen and Thomas the manservant. Despite her many comments on the mead and her requests for the recipe for orange wine, it is highly unlikely that Austen herself would have been the one drawing the water from the well or stoking the fire in the copper.

We can leave supposition and theory more firmly behind, however, when we cross the courtyard and go back into the main house. While this building has seen much change, neglect, and restoration over the two centuries since Austen’s death, thanks to some incredibly lucky survivals from the past, we have been able to restore three of the wallpapers that she herself would have known. The recreation of these wallpapers has allowed us to experience the three rooms in which they hang as Austen would have known them. Like so much under the roof of Chawton Cottage, their significance is multilayered. On one level, like the patchwork coverlet that the Austen women pieced, they tell us a great deal about their style and decorative tastes, as well as providing a snapshot of the art and design of their time. The wallpapers and the coverlet are an extraordinary resource for exploring what Austen would have seen every day; the colors and patterns that surrounded her and her contemporaries.

But the drawing-room and dining-room wallpapers have a deeper significance than this. With the vestibule, these three rooms on the ground floor of the house are some of the most important spaces in the history of the development of English Literature, with an influence that has been felt across the globe. The dining room, with its vivid, arsenic green wallpaper, feels, to me, very much Jane Austen’s room. It was here that she would make breakfast and the family would start the day. But far, far more importantly, it was in this space, in front of the window and against this green backdrop that she would write.

Dining room of Jane Austen’s House with her writing table and Chawton Leaf wallpaper.

Photo by Luke Shears. © Jane Austen’s House.

It is important to understand two things to fully appreciate the significance of this wallpaper. The first is that the road outside the window was, until the 1970s, the main road from London to Winchester and from London to the naval base of Gosport. While Chawton, even in the nineteenth century, was far, far quieter than either Bath or Southampton, it was a metropolis and the road a major highway when compared with the deep valley and tiny country lanes of Steventon. The second is that the plant this pattern is based upon is a dead nettle, a plant that grows in scrubland and on the edges of woods and footpaths. It is a plant of the wild, not the hot house or formal garden. In that, it is much like Elizabeth Bennet—rather than Elizabeth Bennett, the sixteenth century Essex woman, although I suspect that they did have this in common. Austen’s Elizabeth Bennet is also a creature of the wild. Earlier this year, I made a close study of the many walks Elizabeth takes throughout the novel, and it quickly became crystal clear that—far from being confined to the drawing room or ballroom—Lizzy is always outside, always in nature. Very little of consequence in the novel, and almost everything that moves the plot forward—all the walks into Meryton, and then to Netherfield, the meeting between Darcy and Wickham, Colonel Fitzwilliam’s revelations, the apology letter, the meeting at Pemberley, reading Mr. Gardiner’s letter from London, the discussion with Lady Catherine, all the way to the final proposal—they all, and more besides, take place not just outdoors but mostly against an informal, naturalistic background. Elizabeth Bennet is constantly escaping the confines of home (even when she is staying with others) and, like both Anne Elliot and Fanny Price in the later novels, is deeply connected with the natural world around her. She is a child of the Romantic era—she is, unlike the Bingley sisters, no hothouse flower but rather some rambling, robust, wild thing.

When you know that the final drafts of these walks (as well as Anne Elliot’s autumnal wanderings and Emma Woodhouse’s walks around Highbury) were written against the backdrop of this wallpaper, then it is imbued with that extra layer of meaning. This wallpaper is a green screen, reconnecting Austen with the hedgerows and footpaths of Steventon and enabling the creation of the footpaths and walks of her imagination. Today, the wallpaper continues to act as an inspiration for artists and writers to create innovative new works, as well as reminding us all of the inherent wildness of Austen.

Across the vestibule is the drawing room, with its arched gothic window installed by Edward Austen’s workmen as part of the former farmhouse’s prettification into a cottage. The wallpaper here is a rich yellow, with a trailing pattern of rather Italianate vine leaves. I often describe this room as gilded, although there is nothing gold in the room, no gold leaf in the recesses of the door frames as might have been found in a fancier home, and the handful of candlesticks around the room are relatively humble brass. It is the wallpaper that makes this room shine. As in her novels, Austen leaves us little description of the physical space of the house or how the family used it, but on occasion her letters are deeply rooted in the space and reanimate it before our eyes, and from these letters we can see that the drawing room was as central to life at Chawton Cottage as the dining room. It was a place to “work,” to rest, to entertain, and, as we shall see, to perform.

Drawing room of Jane Austen’s House with Chawton Vine wallpaper. Photo by Luke Shears.

© Jane Austen’s House.

![]()

In this final section, you will remember, I want to talk about the author’s voice, which of course, means Austen’s letters. Rare, precious, and with a price tag to match, they are invaluable not just for the essential biographical information they contain but also for the opportunity to hear Austen’s voice in conversation. Her authorial voice is different in each novel. The narrator of Pride and Prejudice is significantly different from that of Mansfield Park, for example, and it would be a mistake to assume that they have the same agenda or bias. Throughout the letters, too, we hear slightly different voices. Austen writes in one way to her brother Frank—teasing, playful, and with touches of both nostalgia and reserve. Her letters to Martha Lloyd are different again, while her letters of business to John Murray and James Stanier-Clarke are no-nonsense, if more than a little passive-aggressive. Austen left no diary, so we never hear her talking to herself, but perhaps the letters to Cassandra are the closest we can come.

We know the content of 161 letters and the whereabouts of even fewer. Many have never re-emerged after Lord Brabourne’s Sothebys sale in the 1890s. Jane Austen’s House owns and co-owns sixteen letters, some ten percent of the total. One of our most recent letter acquisitions was Letter 2, which we own jointly with the magnificent Bodleian Library. It is the earliest Austen letter still in existence and dates from 14–15 January 1796. The physical letter teaches us that, as with her later novels, we shouldn’t always take what Austen says at face value: we can never ignore that constant strain of irony and sarcasm that runs through everything she writes. In Letter 2, her last evening with Tom Lefroy is looming, and she records that her tears flow as she writes “at the melancholy idea.” But her paper is resolutely un-tearstained, her handwriting is as smooth and clear as ever, and she quickly jumps to the next subject.

The letters held at Jane Austen’s House span Austen’s life from January 1796 to the last full year before she died. They are bookended by that letter, written by the young, dancing Austen, the fierce young woman whom young men hid from when she came calling,3 and the astonishing letter written twenty years later to James Stanier Clarke on 1 April 1816 (Letter 138D), when she so strongly states her pride in her writing—still a fierce woman, but one who by 1816 is defining herself by different terms, who is sure of herself, her skills, and her success. In among these letters are a cluster of four written to Cassandra between January 24 and February 9, 1813—a period of just seventeen days, but what a seventeen days for Austen! The letters are dated Sunday 24 January, Friday 29 January, Thursday 4 February, and Tuesday 9 February, and they are all written with Austen’s usual verve and energy, communicating all the family news, frequently with her own added and rather biting commentary. Austen’s letters to her sister over this period document an extraordinary period in Austen’s life—the publication and initial reception by family and friends of Pride and Prejudice.

The period opens relatively, deceptively quietly. On Sunday, January 24, the weather is crisp and cold, and Cassandra has relatively recently left Chawton for Steventon, to stay with James and Mary.

We have had no letter since you went away, & no visitor, except Miss Benn who dined with us on friday; but we have received the half of an excellent Stilton cheese—we presume, from Henry.—My mother is very well & finds great amusement in the glove-knitting; when this pair is finished, she means to knit another. (24 January 1813)

Here we can perhaps place Austen and her mother in the drawing room, on either side of the fireplace, Jane writing while her mother knits. We also see Austen the reader in some detail—or is it Austen the researcher?

We quite run over with Books. . . . I am reading a Society-Octavo, an Essay on the Military Police & Institutions of the British Empire, by Capt. Pasley of the Engineers, a book which I protested against at first, but which upon trial I find delightfully written & highly entertaining. I am as much in love with the Author as I ever was with Clarkson or Buchanan. . . . The first soldier I ever sighed for.

While very much sent from within the sphere of the domestic, it is here that we see the division between home and workplace most starkly. While Austen is eagerly anticipating the publication of one novel, she is also hard at work finishing her next novel, Mansfield Park, and the books she mentions are fascinating considering the subject matter of that novel. Clarkson was a famous abolitionist, while Pasley’s book is less of an exposé and rather more of an endorsement of the nascent British Empire—a conflict of ideas that is reflected throughout Austen’s novels as she both rails against the patriarchy and the establishment and tacitly supports it. The letter, like so many of Austen’s, is full of local and family news, a tangle of names and allusions that represent their complex and interconnected social network. It is written at Austen’s usual pace, with gentle diversions for walks and reported conversations.

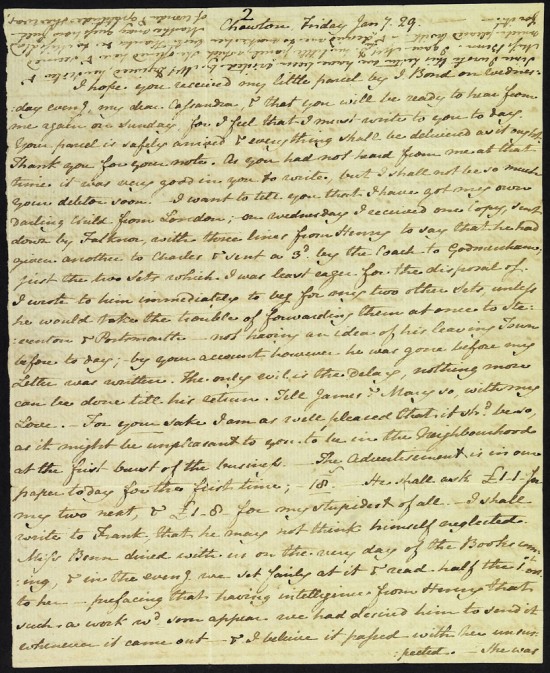

The next letter (29 January 1813) is written at a completely different pace. It brims with excitement and nervous energy, and the opening paragraphs are almost breathless; we can almost feel her irritation at having to open the letter with the usual politenesses and not be able to jump straight into her news:

I hope you received my little parcel by J. Bond on Wednesday eveng, my dear Cassandra, & that you will be ready to hear again from me again on Sunday, for I feel that I must write to you to day. Your parcel is safely arrived & everything shall be delivered as it ought. Thank you for your note. As you had not heard from me at that time it was very good in you to write, but I shall not be so much your debtor soon.—I want to tell you that I have got my own darling Child from London;—on Wednesday I received one Copy, sent down by Falknor, with three lines from Henry to say that he had given another to Charles & sent a 3d by the Coach to Godmersham; just the two Sets which I was least eager for the disposal of. I wrote to him immediately to beg for my two other Sets, unless he would take the trouble of forwarding them at ones to Steventon & Portsmouth.

She goes on to tell Cassandra that the advertisement for the book is in the newspaper and to apologize for not yet getting a copy to Steventon.

29 January 1813, Jane Austen to Cassandra Austen. © Jane Austen’s House.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Then she writes:

Miss Benn dined with us on the very day of the Books coming, & in the eveng we set fairly at it & read half the 1st vol. to her. . . . She was amused, poor soul! that she cd not help you know, with two such people to lead the way; but she really does seem to admire Elizabeth. I must confess that I think her as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print, & how I shall be able to tolerate those who do not like her at least, I do not know.

Again, the house is animated. We can see, hazy though their faces and figures might be, Jane and Mrs. Austen, again in the circle of the firelight, reading the novel aloud, as the author herself embodied the characters she created, bringing them off the printed page for the first time. Austen herself here began the ongoing dramatic interpretation and reinterpretation of the novel that has continued ever since.

She also, in this letter began the critical analysis that we still continue today:

The 2d vol. is shorter than I cd wish—but the difference is not so much in reality as in look, there being a larger proportion of Narrative in that part. I have lopt and cropt so successfully however that I imagine it must be rather shorter that S. & S. altogether.

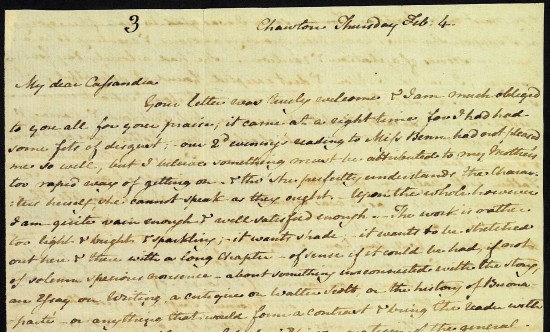

The next two letters continue this analysis: Austen’s letter of 4 February opens:

My dear Cassandra

Your letter was truely welcome & I am obliged to you all for your praise; it came at a right time, for I had had some fits of disgust;—our 2d evening’s reading to Miss Benn had not pleased me so well, but I believe something must be attributed to my Mother’s too rapid way of getting on—& tho’ she perfectly understands the Characters herself, she cannot speak as they ought.—Upon the whole however I am quite vain enough & well satisfied enough. The work is rather too light & bright & sparkling;—it wants shade;—it wants to be stretched out here & there with a long Chapter—of sense if it could be had, if not of solemn specious nonsense.

4 February 1813, Jane Austen to Cassandra Austen. © Jane Austen’s House.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Again, we see Austen alternately confident and self-doubting, testing the waters as the first reactions to her precious novel come in. By the fourth letter in this sequence, the Steventon copy has arrived, and Cassandra has been able to read it in full, as has Fanny Austen at Godmersham. Both have sent Austen their feedback, and she replies: “I am exceedingly pleased that you say what you do, after having gone thro’ the whole work—& Fanny’s praise is very gratifying;—my hopes were tolerably strong of her, but nothing like a certainty. Her liking Darcy & Elizth is enough” (9 February 1813).

By this fourth letter, Cassandra has left Steventon to stay at Manydown, and Austen’s first flush of excitement around the publication has settled a little, the nervous energy around its reception has dissipated, to be increasingly replaced with confidence and pride. All four of these letters are hugely significant, but it is the middle two—those of 29 January and 4 February—that are so incredibly important. They bring Austen the writer vividly to life, but more than this, they link the two periods of intense creativity in her life. Pride and Prejudice, like Austen herself, was born in Steventon; she read the first drafts of “First Impressions” aloud there too, in the girls’ upstairs sitting room. There is something so deeply right, so circular that these key letters should be sent to Cassandra back at Steventon, and that this essential conversation between the two sisters should take place between Steventon and Chawton.

![]()

For an author who has crossed the line between writer and icon, it is crucial to preserve and share her unique voice. Austen’s letters—and these letters in particular—are essential to this effort. Not only do they capture an incredibly intense period in Austen’s life, but they provide an invaluable insight into the thoughts and emotions of the living woman, as well as bringing her experiences in her home to vivid life. They are a key part of the collections of Jane Austen’s House, and they demonstrate what a rich resource lies beneath its roof and within its store. These books, letters, and objects are so full of stories that there are multiple avenues for research to deepen our understanding of Austen’s world. All we need to do is unlock the door of the Collections Store, and step inside.

NOTES

1The Jane Austen Society reports are an excellent resource for tracking the early years of collecting.

2Research carried out on Ancestry.com.

3In Letter 1 Austen writes of Tom Lefroy: “But as to our having ever met, except at the last three balls, I cannot say much; for he is so excessively laughed at about me at Ashe, that he is ashamed of coming to Steventon, and ran away when we called on Mrs Lefroy a few days ago” (9–10 January 1796)