When Colin Firth emerged from a lake in 1995, membership of Jane Austen Societies across the world skyrocketed. Then, in 2005, Matthew Macfadyen flexed his hand. But even before Laurence Olivier picked up a bow and arrow in 1940, readers of Pride and Prejudice were entranced by Fitzwilliam Darcy. Looking at the five readily accessible screen adaptations of Pride and Prejudice (1940, 1967, 1980, 1995, and 2005), we can see that each one draws on Austen’s character but refashions him to suit the conventions and audience expectations of the time, giving us new Darcys for new generations.

Before film: Darcy from page to stage

Viewed objectively, much of Darcy’s behavior at the beginning of Pride and Prejudice could justify Meryton’s view that he is “the proudest, most disagreeable man in the world” (11), but Austen engages the reader’s interest in him, even as Elizabeth despises him. In volume 1 of the novel, the narrator gives us insight into Darcy’s feelings, so by the time of the Netherfield ball, we are very aware that “in Darcy’s breast there was a tolerably powerful feeling towards” Elizabeth (105). Without authorial comments, how do adaptations ensure viewers engage with Darcy from the start? How do they present him as a viable romantic prospect for Elizabeth?

In The Making of Jane Austen, Devoney Looser points out that in the first stage adaptations, Darcy typically “spent much of the play acting in ways that reinforced Elizabeth’s most uncharitable views of the character” (99). But in 1935, Helen Jerome’s adaptation, staged on Broadway, offered the audience “potential for immediate sympathy with hero and heroine” (Looser 110). The stage directions indicate that Darcy is to show passion, and Colin Keith-Johnston’s performance seems to have been “designed to set hearts, and all manner of female parts, aflutter” (Looser, “Sexed-Up”). A passionate Darcy is quite a departure from the novel, and Jerome’s script may have helped pave the way for later reinterpretations.

One approach common across most screen versions is to position Darcy’s early behavior as driven by something other than pride, although the driving force varies by adaptation. Another recurring, though not universal, theme is for the actor, through facial expression and body language, to give the audience access to his inner self—although the emotions displayed are not necessarily those described by Austen’s narrator.

1940: Laurence Olivier, matinee-idol Darcy

© 1940 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

The first big-screen adaptation of Pride and Prejudice was the 1940 MGM film, with Helen Jerome included in the writing credits (although little of her play made the final film). Darcy was played by Laurence Olivier, fresh from starring in Wuthering Heights and Rebecca, who brought matinee-idol glamour to the role. He later said it was “difficult to make Darcy into anything more than an unattractive-looking prig” (183), but to many in the audience, Olivier’s screen presence alone was enough to make them love the character. Rather than passion, he imbues Darcy with charm. John Wiltshire describes him as “a smiling Darcy” (50), and the way he embarks on his first proposal, with a sigh and an almost self-deprecating tone, seems more boyish than arrogant, and leads us to be more indulgent towards him.

John Wiltshire describes Olivier as “a smiling Darcy.”

The screenplay makes a number of cuts to the plot—most notably a complete excision of the Pemberley section—and the romance between Darcy and Elizabeth is given a completely different shape from that of the novel. The film was positioned within the screwball comedy genre popular at the time, which favored lively repartee, strong female characters, and class-crossing relationships. Thus far, parallels to Pride and Prejudice are clear, but other screwball elements were overlaid, such as a series of almost-connections between the leads, an innovation that significantly changes Darcy’s character trajectory. Instead of resisting his feelings through to the Rosings encounter, this Darcy clearly “responds to Elizabeth from the start” (Wiltshire 50), and he and Elizabeth, as Ellen Belton characterizes it, “seem continually to be on the verge of moving to a new level of intimacy but to be prevented from achieving it by some misunderstanding or accidental reminder of the superficial differences between them” (193).

Darcy’s changed trajectory is particularly apparent at the Netherfield garden party (a replacement for the Netherfield ball). Darcy condescendingly offers archery advice to Elizabeth, only to find that she is more expert than he.

© 1940 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

His gracious response—“Next time I talk to a young lady about archery, I won’t be so patronizing. Thank you for the lesson”—and Elizabeth’s “Thank you for taking it so well. Most men would have been offended” could have come out of the screwball comedy playbook, with its emphasis on capable women, witty banter, and a battle of the sexes. Shortly afterwards, Darcy suggests friendship—“Shall we not call it quits and start again”—only to draw back completely after overhearing Mrs. Bennet talking about Jane and Bingley, witnessing an inebriated Kitty, and being accosted by Mr. Collins. This failure to connect is seen again in the proposal scene, and yet again after Lydia’s elopement—so, rather than the proposal being a key turning point in the story, it is simply one (albeit the most significant) in a series of short-circuited opportunities.

After connecting with Elizabeth during the archery scene, Darcy then turns away.

This changed character trajectory, combined with Olivier’s innate screen presence and the boyish charm with which he imbues the role, seems designed to engage the audience with Darcy from the start, rather than risk viewers’ being repelled by his pride.

1967: Lewis Fiander, controlled Darcy

Reinier Wels’s excellent article “Pride and Prejudice in Black and White: First and Last Impressions (1938–1967)” outlines the numerous pre-1980 television adaptations. The only one of these readily available today is the 1967 BBC version (available on YouTube), with Australian actor Lewis Fiander as Darcy.

© 1967 BBC.

To modern viewers, this production suffers not only from the poor quality of the recording, but also from the somewhat declamatory style of speaking, and Darcy’s rather bouffant hair (after being given the part, Fiander was told to “start letting [his] hair grow” [Colville 25]).

This Darcy has rather bouffant hair.

Instead of Olivier’s charm, Fiander’s alternative to “pride” is to give us a character who exercises control over his emotions. Darcy initially appears calm and aloof, but in an added scene Wickham appears at the Netherfield ball, and Darcy approaches him with controlled anger: “You will either leave this house of your own volition, or I will have the servants remove you by force.” This anger is not something we see in the Darcy of Austen’s novel, and it is quite a different style of passion from Jerome’s Darcy.

Darcy’s growing attraction to Elizabeth is shown in the increased softness in his eyes after their dance; and when they meet at Rosings he even smiles when talking to her. Fiander’s changing facial expression is consistent with the novel. When Elizabeth sees Darcy’s portrait at Pemberley, she observes it has “such a smile over the face, as she remembered to have sometimes seen, when he looked at her” (PP 277). John Wiltshire points out that “the reader has never noticed Darcy’s smile before” (49). Fiander gives us this smile, providing access to Darcy’s feelings, and a reason to connect with him.

And yet, there seems little emotion in the opening lines of his first proposal. When he is refused, we again see controlled anger, and then a close-up of his face as he says, “And this is your opinion of me. This is the estimation in which you hold me. I thank you for explaining it so fully.”

© 1967 BBC.

As he pauses between each sentence, it appears that he is processing and beginning to reflect on what Elizabeth has said. This Darcy does not write a letter to Elizabeth. Instead, they meet, and he explains his actions in person, providing Fiander scope to show emotions in his face, finishing with an appeal in his eyes at “I have said what I have to say, and I ask you to consider it without prejudice.”

As would happen again in 1995, we see something of Darcy’s actions after Elizabeth leaves Pemberley: in this case, his negotiating with Wickham. Darcy’s self-control is positively icy, as he coldly agrees to make a payment and sets conditions. In consequence, when he returns to Longbourn, and is much as he was in the opening episodes, we now have evidence (which Elizabeth does not) of his actions, and we also have a greater understanding of what lies behind the controlled façade. Emotion returns to his face in the second proposal, and the production finishes with his bringing Mrs. Darcy home to Pemberley.

“Welcome home, Mrs. Darcy.”

Thus, Fiander’s initially rather stiff and unemotional presentation can be understood, in retrospect, as control rather than pride. The extent to which we see controlled anger may be somewhat concerning to modern viewers, but perhaps less so in the 1960s. And the use of facial expressions as he looks at Elizabeth gives us access to his changing emotions. We realize that he does love and deserve her.

1980: David Rintoul, reserved Darcy

© 1980 BBC.

In 1980, the BBC released its first color adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, with David Rintoul as Darcy. Deborah Cartmell points out that it was made during a drama “turf war” between the BBC and ITV, typified by innovative productions of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1979, BBC) and Brideshead Revisited (1981, ITV). The 1980 Pride and Prejudice was very female-centric, perhaps partly as a contrast to the male-centric Brideshead and Tinker, Tailor, and partly due to the feminist views of screenwriter Fay Weldon. Cartmell argues that this adaptation “privileges the relationship of [Elizabeth and Jane] above that of the obligatory heterosexual pairing of Darcy and Elizabeth” (64).

While Elizabeth expresses her thoughts in voiceover, Darcy does not get to speak about his emotions. Furthermore, we are given little insight through his acting: Devoney Looser describes Rintoul’s performance as an “ultra-stiff attempt” (“Mr. Darcy through the Ages”), while Henriette-Juliane Seeliger says “Throughout the series, his facial expression and body language almost never change.”

Listening to Mary playing the piano (left), and to Elizabeth playing (right): there is very little change in facial expression.

As a result, the Darcy the audience sees is exactly the haughty Darcy that Elizabeth sees—although it is worth noting that the emphasis is on reserve, rather than pride. His face is almost invariably still, with a slight frown; he holds himself quite upright; we do not know what he is thinking as he stalks around the room, often looking at the walls or out windows rather than at his companions. This stiffness may be a feature of the actor (it can be seen, to a lesser extent, in some of his other performances), but we must also assume that it was a deliberate choice by the filmmakers to maintain his remoteness—perhaps to keep the focus on Elizabeth.

And yet, there does seem to be one attempt to “humanize” him. As Darcy walks to the Parsonage, on his way to propose to Elizabeth, he is accompanied by an English Pointer dog. Arriving at the door, he tells the dog to stay, and we see it looking quizzically at him.

© 1980 BBC.

But the proposal scene itself reverts to reserve: he enters with the habitual frown on his face, and his voice is equally without emotion. Following Elizabeth’s refusal, we do see both anger and hurt, but unlike Fiander, who was visibly controlling his emotions, Rintoul’s Darcy seems almost constitutionally unable to let his feelings overcome his reserve.

At Pemberley, there is some relaxation in Darcy when he joins Elizabeth and the Gardiners by the lake—a softer facial expression, even a smile, and more conversation. While Rintoul is not displaying deep emotion, he is finally giving us a Darcy who is not “ultra-stiff.” But after Elizabeth has revealed Lydia’s story, the mask returns, and on his first visits to Longbourn afterward, he has returned to impassivity: Elizabeth smiles at him, but there is no response in his eyes. The events after Lady Catherine’s visit are condensed into a single walk, and throughout Darcy’s second proposal he looks straight ahead, rather than at the woman he wishes to marry. It is not until she accepts him that he turns to face her, and, with a slight smile on his face, offers her his arm. As they continue their walk and conversation, we finally see him relaxed, smiling, and making eye-contact.

When Elizabeth accepts his proposal, he turns to face her, and, with a slight smile on his face, offers her his arm.

For some viewers, David Rintoul captures exactly the character of the novel: his extreme reserve is both very English and very Darcy. Unfortunately, while reframing pride as reserve may prevent the audience from being actively repelled by the character, it does not necessarily make him engaging. As Cartmell points out, this production is more focused on Elizabeth than Darcy, and while Elizabeth Garvie is generally well-regarded in this role, for most people Rintoul’s legacy is a Darcy who is stiff and distant and who never gives enough access to his emotions to make him a viable romantic prospect for Elizabeth.

1995: Colin Firth, sex-appeal Darcy

© 1995 BBC.

The 1995 BBC production of Pride and Prejudice, where Darcy is played by Colin Firth, is often credited with giving us “socially awkward Darcy.” At the Meryton assembly he looks not so much proud, or reserved, or aloof, as uncomfortable and somewhat grumpy. He doesn’t want to be there, and when Bingley pressures him to dance with Elizabeth, he responds with irritation. Colin Firth described his interpretation as follows:

I agree to go to a party with my friend Bingley. . . . I’m terribly shy—terribly uneasy in social situations anyway. This is not a place I’d normally go to, and I don’t know how to talk to these people. So I protect myself behind a veneer of snobbishness and rejection. (Birtwistle and Conklin 101)

Darcy is uncomfortable and grumpy.

There is support in the text for this interpretation. At Rosings, when Darcy is defending himself against Elizabeth and Colonel Fitzwilliam’s banter (another scene in which Firth’s Darcy is visibly uncomfortable), he says, “‘I certainly have not the talent which some people possess . . . of conversing easily with those I have never seen before. I cannot catch their tone of conversation, or appear interested in their concerns, as I often see done’” (PP 197).

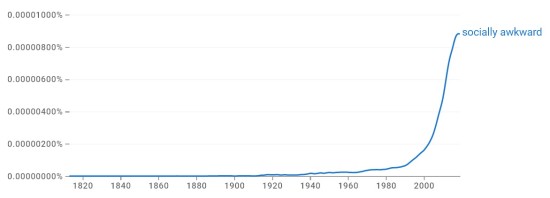

None of the earlier adaptations used social awkwardness as an alternative to pride, but it may have been in the zeitgeist of 1995, as the other, lesser-known 1995 adaptation (an episode of the children’s series Wishbone) also had a Darcy who is “nervous about parties.”1 Furthermore, socially awkward Darcy can be found in most adaptations and modernizations since that time.2 It is interesting to place this trend alongside general popularity of the term “socially awkward,” for which a Google Books Ngram search shows an exponential rise in usage from around 1991:

But while this may suggest a causal connection, we should not forget that every post-1995 adaptation has access to those that came before, and so the influence of Colin Firth cannot be discounted.

Even more than socially awkward Darcy, the 1995 production emphasizes sex-appeal Darcy—perhaps for the first time since Jerome’s Broadway play, sixty years earlier. Firth’s Darcy engages in masculine pursuits less available to a stage Darcy, such as riding, shooting, and fencing. Screenwriter Andrew Davies said that the opening scene of Darcy and Bingley on horseback is designed “to show them as two physical young men. . . . I wanted the audience to get a sense fairly early on that there is a lot more to Darcy than Elizabeth sees” (Birtwistle and Conklin 3, 5). The emphasis on physicality also drives scenes such as Darcy’s taking a bath or plunging into his lake.

Alongside this presentation of Darcy as the male animal, Davies said an aspect of Pride and Prejudice that he was struck by “is that the central motor which drives the story forward is Darcy’s sexual attraction to Elizabeth” (Birtwistle and Conklin 3). Darcy’s sex-appeal arises not just from his physicality but from the insight we get into the emotional journey. The novel’s comments about his growing preoccupation with Elizabeth are shown here by how he looks at her. Initially he has a slight frown, but in a later gathering he gazes after Elizabeth, his eyes soft, with the beginning of a smile on his face. This softening is not original: we saw something similar on Fiander’s face in 1967, but for Firth this smile will grow throughout the series. The inscrutable frown recurs, but increasingly we see the smile.

Firth’s Darcy is clearly in a highly emotional state for his first proposal—a marked contrast to Rintoul, Fiander, and even Olivier. Breathing audibly he looks at Elizabeth, and then away from her; walks up and down; takes a seat and then stands up again immediately; and finally faces her, with words bursting out almost against his will.

The most well-known scene from this (or possibly any) production is “wet shirt” Darcy, having plunged into the lake, then unexpectedly encountering Elizabeth at Pemberley.

© 1995 BBC.

This moment ties in with the “male animal” aspect that Davies wanted to emphasize, but it also serves the emotional story, highlighting the acute embarrassment he and Elizabeth feel. Unlike previous Darcys, there is a sense of urgency in the Pemberley scenes: Firth said he “needs to show her in about three minutes flat that he is prepared to be apologetic and tender and amenable and unsnobbish. He’s just got to get a foot in the door and prove that he has tried to change those aspects of his nature that alienated her before” (Birtwistle and Conklin 104). But in quieter moments, there is also the smile—softer, more open, and a naked display of his feelings.

The final shot of Darcy is in the carriage with Elizabeth after the wedding, with a broad smile of delight on his face. His emotional journey, which began with a gaze, a softening of the eyes, and a faint smile, has now ended in perfect happiness. And the viewer, who has been with him almost every step of the way, is invited to celebrate.

2005: Matthew Macfadyen, emo Darcy

© 2005 Focus Features.

The 2005 film Pride & Prejudice, with Darcy played by Matthew Macfadyen, was the first big-screen adaptation since 1940. The plot focuses almost entirely on the romance between Elizabeth and Darcy, but unlike the 1940 version, it doesn’t change the character trajectory. A product of a different time, it keeps (at least until the final scenes) the essential structure of the novel, but presents it as a capital-R Romance, with luscious cinematography and a mood that at times leans more towards the Brontës than Austen. Darcy is again reinvented, for a new century and an audience that extends into the young adult demographic.

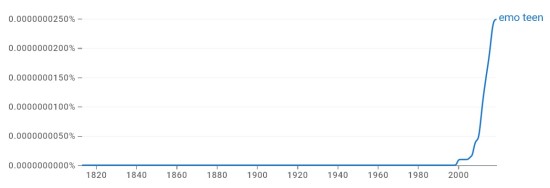

Macfadyen viewed Darcy as “a tortured adolescent . . . he’s sort of all conflicted and torn up” (Macfadyen). On Darcy’s first appearance in the film, Elizabeth remarks that “he looks miserable, poor soul,” explicitly telling us how to interpret his somewhat dour, morose expression. This film came out in a decade that also saw publication of the young adult fantasy series Twilight—partially inspired by Pride and Prejudice, but in which the characters explicitly identify with Wuthering Heights—and the growth in usage of the adjective “emo” to describe a person who likes emo (emotional, hardcore punk) music, wears mainly black clothes, and is depressed, sensitive or emotional, often performatively so. A Google Books Ngram of the term “emo teen” places the first use in 2000, with an exponential rise from 2004.

Joe Wright’s film provides another socially awkward Darcy, but a differentiating factor is that while Firth’s Darcy dislikes being in a crowd, would rather be elsewhere, and is annoyed with Bingley for bringing him to the assembly, Macfadyen’s rather seems to regret that he doesn’t know how to fit in. When Elizabeth asks whether he dances, he responds abruptly, “Not if I can help it,” but when she then turns away from him, he looks sadly down at the floor.

© 2005 Focus Features.

Macfadyen’s Darcy is powerfully drawn to Elizabeth, and we see this attraction in his gaze, but rather than softening from coldness into smiles, as did Firth (and Fiander), the “torture” Macfadyen has commented on seems to increase. His face remains on a “miserable” setting, with occasional shifts into anger, defensiveness, or anxiety, as he is unable to deal with his emotions. His attraction to Elizabeth is also shown through physical response. One of the most meme-ed examples is at Netherfield, when Darcy hands Elizabeth into a carriage: as he walks away, his hand briefly flexes in response to the physical contact. As his inner conflict grows, he engages the sympathy or the empathy—or both—of an audience attracted by romantic suffering.

Macfadyen’s Darcy gazes at Elizabeth: his growing attraction increases his misery

The production also uses setting and weather to create a sense of heightened emotion—Brontë-esque romance, twenty-first century style. For example, the first proposal scene is no longer indoors, with Elizabeth and Darcy constrained by four walls and early nineteenth-century propriety: rather, it is outdoors, with both participants wet from the rain. The charged mood is emphasized by the participants’ disheveled appearance and the tumultuous weather, while Darcy’s declaration, in which his built-up emotion comes bursting out, includes emotive language such as “torment” and “agony.” During the argument, he steps very close to Elizabeth: they are not quite touching, but the sexual tension is palpable.

The second proposal scene is even more of a tonal departure from the novel. Walking in the fields at dawn, wearing only a coat over her nightdress, Elizabeth sees Darcy—also casually attired—emerging through the mist. In keeping with this hyper-romantic approach, while Darcy initially uses words from the novel, he transitions into highly charged language: “You have bewitched me, body and soul, and I love—I love—I love you.” The scene finishes with a close-up as Elizabeth takes his hands, he presses his forehead against hers, and the sun rises between them. In the DVD director’s commentary, Wright acknowledges that this scene may be “a bit over the top and a bit over romantic and a bit slushy.” It is certainly a very long way from Jane Austen’s text, but it is absolutely in keeping with the approach of the rest of the film.

Wright says this scene may be “a bit over the top and a bit over romantic and a bit slushy.”

![]()

Pride is a key element of Austen’s Darcy. Even at the novel’s end, Elizabeth says that “‘he has no improper pride’” (417) rather than that “he has no pride,” but the screen adaptations generally sidestep this complexity. On his initial appearance, Darcy seems aloof or distant or reserved or perhaps socially awkward or miserable, before going through an emotional journey that is slightly different in each case but that always brings him to Elizabeth.

From the screwball comedy fans of the 1940s, through to the Twilighters of the 2000s, every generation of filmgoers and television-watchers has different expectations of a romantic lead. An adaptation will always be the product of its time, and decisions of what to include, drop, or change will be driven by an understanding of the audience. Matinee-idol Darcy, Controlled Darcy, Reserved Darcy, Sex-appeal Darcy, and Emo Darcy all combine Jane Austen’s 1813 creation with the expectations of very different contexts. They give viewers unversed with the book a “way in” to the character, while providing existing Austen fans with ideas to think about, whether they agree or disagree, that may ultimately offer them new perspectives on the original.

NOTES

The clips used in this essay satisfy the criteria for fair use established in Section 107 of the Copyright Law of the United States of America and Related Laws Contained in Title 17 of the United States Code.

1Wishbone retells works of literature, with the Jack Russell terrier Wishbone playing a key role (other parts are played by human actors). In the episode “Furst Impressions,” Darcy (Wishbone) is introduced with the line “Mr. Bingley’s rich and incredibly handsome friend, Mr. Darcy, is nervous at parties. So nervous he seems rude.” This episode of Wishbone aired in the U.S. on November 9, 1995, less than two months after the U.K. release of Pride and Prejudice. It therefore seems unlikely that either production influenced the other.

2These include the 2004 modernization Bride and Prejudice (American Darcy is out of his comfort zone in India), the 2005 Pride & Prejudice, the 2012–2013 web series The Lizzie Bennet Diaries (with a fan portal entitled “Socially Awkward Darcy”) and 2022’s Fire Island (Will displays a combination of reserve and social anxiety).